How to Hedge A Retirement Portfolio

If you have a retirement portfolio, chances are it has a lot of equity exposure. Your biggest fear probably relates to the capital losses that could occur.

Unlike your house, its value isn’t marked to market each day like the stocks you own, so the latter gets a lot more attention in terms of how to manage and hedge that risk. Stocks are volatile and they go through periods where they can drop in value significantly.

This is true whether you own individual stocks, certain types of ETFs, or just stick to owning “the market” and nothing more.

Peak to trough, the S&P lost:

– 51 percent from October 2007 to March 2009 during the 2008 financial crisis period

– 80 percent (for the NASDAQ) during the tech bubble collapse from March 2000 to October 2002

Any kind of leverage would have exacerbated these losses. Equities are already some of the most volatile things you can own because stocks are inherently leveraged (companies have debt).

Common shareholders are the most junior stakeholders in a company’s capital structure. Stock is ownership in a business. You get paid last and also bear the risk if the business fails – much more so than creditors, who receive a higher claim to common shareholders.

Many retirement portfolios reallocate from stocks to bonds as time goes on to reduce this risk. They’re essentially putting themselves more senior in corporate capital structures.

But it also reduces return and is a generally suboptimal approach, as we’ve gone through in other articles.

There are better ways to hedge stocks, which we’ll cover below. Everyone has differing levels of comfort with various strategies, so we covered more than ten.

No matter if you’re holding individual securities and suffer painful drawdowns from bad quarterly reports or bad circumstances, or owning the market, here are some helpful strategies on how to hedge a retirement portfolio.

What is hedging?

Hedging is used to reduce the risk of loss to an investment.

How do you hedge?

Hedging often involves using a type of security or derivative that will typically increase in price when a particular security or portfolio drops in value.

The profit that comes from the hedge will help to offset some or all of the losses sustained by a portfolio.

In certain cases, a hedge can offset more than all of a loss. But most traders and portfolio managers size their hedges in such a way that helps offset loss to only a certain extent. Hedges involve costs and trade-offs.

For example, an easy way to prevent losses on stock investments is to use an at-the-money (ATM) put option on the entirety of the investment.

However, these hedges are expensive. Puts on equities are more expensive than calls because people pay more for risk-off insurance.

And the costs of these tight hedges may offset the entirety of any gains and then some. In other words, your core position (long equities) may gain but still lose money overall because of the sheer cost of the hedge.

Various strategies work to hedge certain types of risks.

For instance, if you own a stock, that’s a linear type of exposure. So a hedge on stock exposure hedges delta (price) risk.

If you own an option, that’s a non-linear exposure. So if you wanted to hedge option exposure that might involve hedging gamma.

There are also matters like:

– foreign exchange (FX) risks

Or even risks that you aren’t aware of due to oversights or blind spots.

For example, if you own airline stocks, you are also implicitly making a bet on the price of oil.

If you are a farmer, you’re implicitly making a bet on the price of various types of crops and other commodities (e.g., soybeans, corn, wheat, cattle, hogs, and so on).

A jeweler has a bet on the prices of various types of metals (e.g., gold, silver, platinum) and different types of stones (e.g., diamonds).

Even companies like McDonald’s can get squeezed if the prices of various types of commodities go up. If the price of cattle or wheat goes up, then the cost of making a hamburger increases as well, and that can vary by country.

How to hedge equity risk

Hedges may protect:

- a single security

- an entire market exposure

- a specific sector exposure, or

- a particular type of risk (e.g., inflation, FX, duration, etc.)

For example, a trader that specializes in tech stocks will know that his or her portfolio will be more sensitive to interest rates because of the longer duration nature of tech companies.

In other words, their cash flows are discounted to come further out in the future relative to other types of companies that make money in the present. This makes them more sensitive to fluctuations in the term structure of interest rates.

This, in turn, gives them higher volatility in a structural way because they’re more vulnerable to a rise in interest rates.

And not only that, but a lot of them are simply speculative business models where the cash flow (revenue above expenses) is uncertain unlike more traditional, established businesses.

A trader with a tech-heavy portfolio might accordingly want to reduce some of this exposure to interest rates. This could mean shorting government bonds or interest rates outright or owning options contracts that could benefit from a rise in interest rates (e.g., puts on eurodollar futures, fed funds futures).

Some traders might also choose to hedge overall market risk instead of the individual securities in their portfolio.

Typically, options on products that involve broad market exposure are more liquid – e.g., SPY options. They are also generally cheaper because the index represents a diversified basket of securities.

Unlike individual stocks, which commonly rise and fall in price rapidly, indices tend to be more stable. Therefore, their options are cheaper.

It’s fairly common for a stock to go up or down more than 5 to 10 percent in one day (or more) – even for larger companies with market-leading positions in what they do. But this occurs rarely with diversified indexes.

And because of their liquidity, their spreads are tighter, which reduces trading costs.

Moreover, many options on individual securities are only tradable with one duration per week. Many have just one duration per month.

And some stocks – especially smaller caps – don’t have any options markets at all. Other securities have options markets with spreads so wide that they’re basically unusable.

Leaving individual securities unhedged leaves a trader open to idiosyncratic risk.

However, if an individual security presents too much risk in a portfolio, the position size should probably be reduced.

That way one security alone won’t create undesired volatility or risk excessive capital loss.

The best type of hedge

Hedging at the overall portfolio level would generally be done with respect to an index.

If a US portfolio is more evenly weighted toward large cap stocks, and most stock portfolios are, hedging based on the S&P 500 index could make sense.

The NASDAQ might be more appropriate if a portfolio is more tech-weighted.

The Russell 2000 might be a better match if there’s more of a bent toward small caps.

None will be perfect. But a reasonably good hedge with low transaction costs could be constructed using an index.

As mentioned above, because many stocks are included in an index – often hundreds – it is less volatile.

Accordingly, the hedge on an overall market index in the form of a put option is cheaper than going security by security.

Owning an option is essentially insurance. You pay a fee for someone else to manage the financial liability associated with the risk of a certain outcome.

And you can also buy other assets to help you manage risk. For example, bonds are a popular way to diversify equities because they do well in different conditions. The same is true with gold.

Short selling can also be a type of hedge. It seems risky and is risky if not done in a thoughtful way, but it can also be cheaper than having to bear the cost of put option premiums.

Hedging a retirement portfolio will be inherently imprecise

Hedging is inherently imperfect. If you took no risk you would have practically no upside. Risk can never be removed entirely and only part of a portfolio will be hedged.

The “risk-free” rate in the market is the government bond interest rate (if you’re in a reserve currency country where they’ll always pay at least in nominal terms).

Return will tend to be proportional to the amount of risk taken on and maximizing return for each unit of risk taken on is key.

Ways of hedging a retirement portfolio

Hedging can involve any type of transaction or measure designed (at least partially) to prevent losses somewhere else.

Hedging might involve options. It might involve buying or selling something.

It can come in the form of portfolio construction or how a trader thinks about the portfolio in a strategic sense

An option contract gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a security or asset at a specific price.

For instance, one GOOG 3000 call gives the buyer the right to buy 100 shares of Google stock (GOOG) at a strike price of $3000 per share.

- A European option can only be executed if in-the-money (ITM) on the expiration date.

- An American option can be executed at any point before the expiry date, if ITM.

A call option gives the buyer the right to buy a certain amount of the underlying asset – 100 shares in the case of a standard vanilla stock option – at the strike price.

A put option gives the buyer the right to sell a certain amount of the underlying asset at the strike price.

- The price paid for an option is called the premium.

Deep OTM options are less expensive because they have less intrinsic value.

In other words, they have a low probability of landing ITM. Accordingly, their price is cheaper.

This reflects the likelihood that they’ll only occasionally have value at expiration or that they have a relatively low probability of having value.

Deep ITM options are more expensive because they have more intrinsic value. The more ITM an option gets, the more the option begins acting like the underlying asset.

Therefore, from a hedging perspective, OTM options work less effectively than ITM options at hedging the underlying.

But the trade-off is their price. ITM options are more expensive than OTM options, sometimes significantly so.

For this reason, many traders like using OTM options to hedge rather than ITM options.

An option hedge is a limited-risk way of reducing the impact of a decline or adverse move in another part of a portfolio.

Hedging can be done with just a single type of option or it can be accomplished with multiple options.

For example, if a trader owned 1,000 shares of Apple stock (AAPL) at $150 per share and wanted to limit potential losses to $10,000 on the position, then he would buy 10 contracts of $140-strike put options.

The 10 contracts cover the 1,000-share total. And the $140-strike covers the $10,000 loss. Of course, there would be a premium associated with this that the trader would have to pay.

If the cost of hedging with 10 contracts costs $2,000 between the premium, commissions, and transactions costs (i.e., the spread), then the total potential loss would really be $12,000.

This cost could be offset, at least to some degree, by gains in the shares and selling covered calls. But that’s getting into something more complicated, which we’ll also talk about below.

We’ll go through each strategy individually.

These will include the following 12 strategies:

- Covered call

- Put option

- Put spread

- Collar

- Fence

- Short selling

- Inverse ETFs

- Owning volatility

- Diversifying

- Reducing position size

- Cash

- Call option

1) Covered call

A covered call entails selling (aka writing) a call option on a stock (or security) you already own.

This has the effect of capping your upside on your gains. But it brings the benefit of having a weak hedge in the case of a decline.

For example, let’s say on Apple (AAPL) you wanted to cover your position at $140 per share. You believe at that price it’s relatively high and a good place to sell if you had the opportunity.

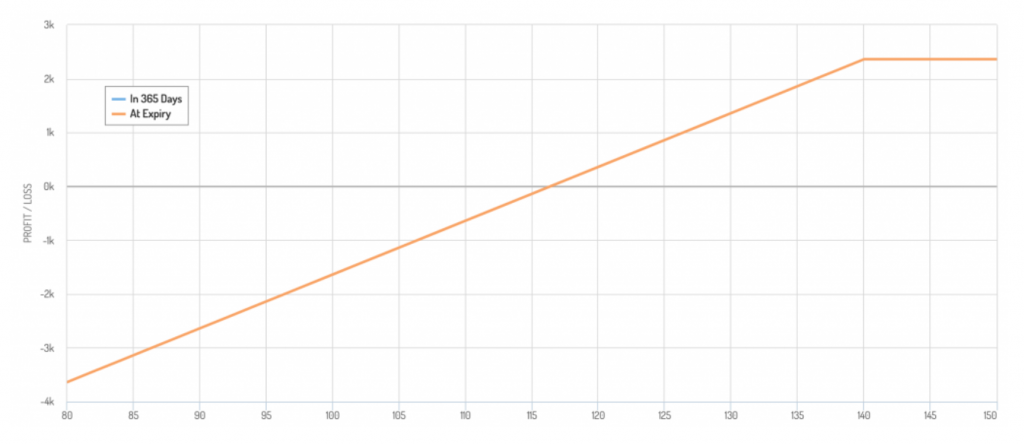

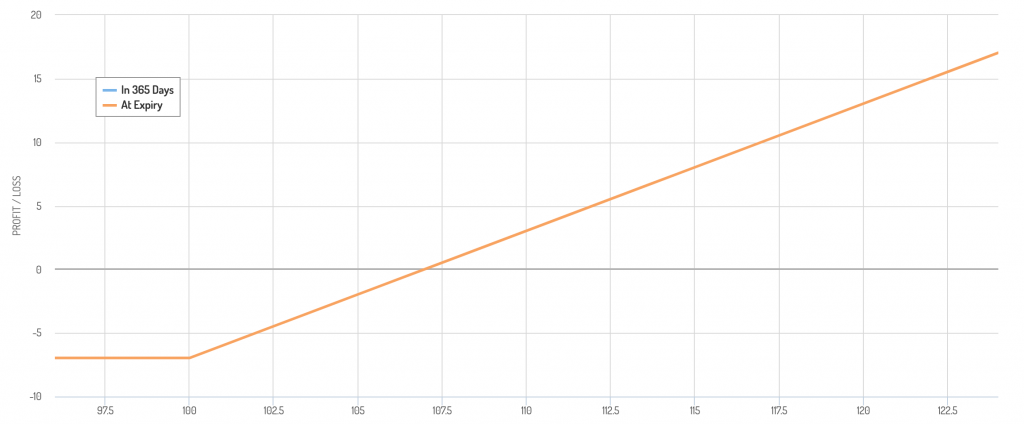

Covered call payoff diagram

A 140 strike call with an expiration one year out might cost around $760. You sell this as part of the covered call, so you’re entitled to this premium.

If the stock is trading at $130, $760 divided by $13,000 (the price of 100 shares, given 100 shares per options contract) is about 5.8 percent.

Based on this, you have upside of about 7.7 percent ($140 divided by $130) and you get the 5.8 percent premium. Your total upside is about 13.5 percent.

If you’re an investor or trader in Apple – a consumer staple tech stock, or a more defensive kind of stock for that sector – you might think that’s not too bad.

Your downside is that you can’t participate in more upside than that 13-14 percent. Your hedge is also quite weak, as it only hedges against about a 6 percent loss.

A covered call will protect you from some losses, but it won’t protect you from a lot.

If a stock you own falls while you have a call option written against it, it will work less well as a hedge if it falls further. This is because it fell further OTM.

You can cover your existing call and sell another one that’s closer to the current price, but this further limits your upside. Lowered enough, you limit or even eliminate any investment gains.

Short call paired with a long put?

To limit possible downside, many traders like pairing a covered call with a long put option. (This is typically called a collar.)

This places one’s upside and downside within a fixed band.

This type of trade structure takes advantage of the volatility risk premium (VRP) and the moderate hedging benefits that come with a short call.

But the long put involves having more clearly defined downside protection.

We’ll cover the collar in more detail in section 4 of this article.

2) Buy a put option

Buying a put option is perhaps the most basic way to hedge a portfolio.

A long put option is a simple way to cut off the so-called left tail of your distribution. This limits your losses.

At the same time, it tends to be expensive.

Options sellers often sell them at a slight premium, such that the implied volatility of the option is likely to be greater than realized volatility of the underlying asset.

Let’s say you own 100 shares of Apple (AAPL). Assume it trades at $130 and you want to cap your downside at $100 per share.

In other words, you don’t want to risk more than about 23 percent of your position.

For a year-long hedge, it would cost around $3.00 per share.

$3.00 per share comes to around 2.3 percent.

In some years, you will lose more than 23 percent of your investment and this hedge will come in handy.

But it’s also going to consume a lot of your returns over time.

You can also lose money on the investment, but in sums smaller than 23 percent and bear the unrealized loss plus the loss in premium from the option hedge.

The option payoff diagram looks something like the image below. Risk is capped at a downside of $100 per share. Breakeven is slightly above the current price ($130). This is because gains are required to help offset the cost of the option.

Long put option payoff diagram

There are also issues like the wide spreads that typically exist in the options markets of individual stocks.

Because of the difficult economics, many traders will limit their exposure to individual securities rather than hedge them directly.

For example, if you have 20 percent of your portfolio in a certain company’s stock, a decline of 50 percent or more would wipe out at least 10 percent of the overall value of a portfolio.

So, it would be better to diversify if this would be unacceptable. Limiting it to say two percent would be more palatable; now a 50 percent drop in a security would be a hit of just one percent.

Concentrated portfolios are common, particularly among newer traders. Many think it’ll give them better gains or because of conviction.

However, markets already price in the discounted set of expectations. That’s what forms the price. So from this perspective, there is no easy good or bad bet on a risk-adjusted basis. You can never be too sure about anything.

As a result, many market participants don’t put any more than about five percent of their portfolio value into anything.

Some go even further down to around 1 percent. This can also mean something like index funds or ETFs to get broad, diversified exposure.

When position sizes increase, this creates a bigger need to hedge. Naturally, this can be expensive and reduce your long-term gains. This has also been found in the academic literature.

When traders hedge, they’ll typically use OTM options.

OTM options will be cheaper than something close to at-the-money (ATM), but they won’t protect the portfolio against the initial declines against the asset.

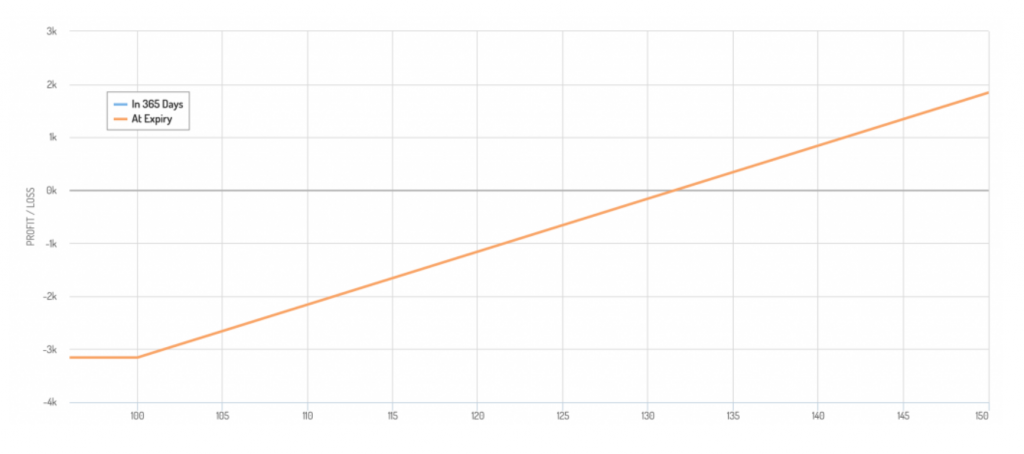

3) Put spread

Want a hedge on something you own but owning put options outright is too expensive?

You can try a put spread.

A put spread entails being both long and short put options on the same underlying asset.

A put spread is used to lower the cost of the hedge. Some of the premium received from the short put will help offset the cost of the long put.

The hedge is still mostly the same but covers only a portion of the price range.

Taking our previous example of Apple stock (AAPL), if you wanted tighter risk management, instead of a 100 strike put, you could buy a 115 strike put.

Your premium will be a lot more, from about $300 for one contract to about $800.

Instead, you could sell the 90 strike put, which provides you that $200 in premium.

The cost of your overall hedge is the difference between the two – $800 minus $200 = $600

$600 is more expensive than $300.

But you pay $300 more to potentially save an additional $1,500 in prospective losses.

The put spread structure gives you the chance to have tighter risk management while not significantly increasing your cost in relation to just put options alone.

The implication of this is that the put spread effectively causes your hedge to “roll off” at a point.

Gains on the long put could eventually be offset by losses on the short put. You will also be long the stock (assuming you still have the exposure).

However, if the stock were to drop more than 20-25 percent you might not necessarily care about being hedged a lot.

That drop in price could be an indication that you’d like to buy more of the stock.

If you have a 115-90 put spread on that means your linear risk exposure to the stock kicks back in below $90.

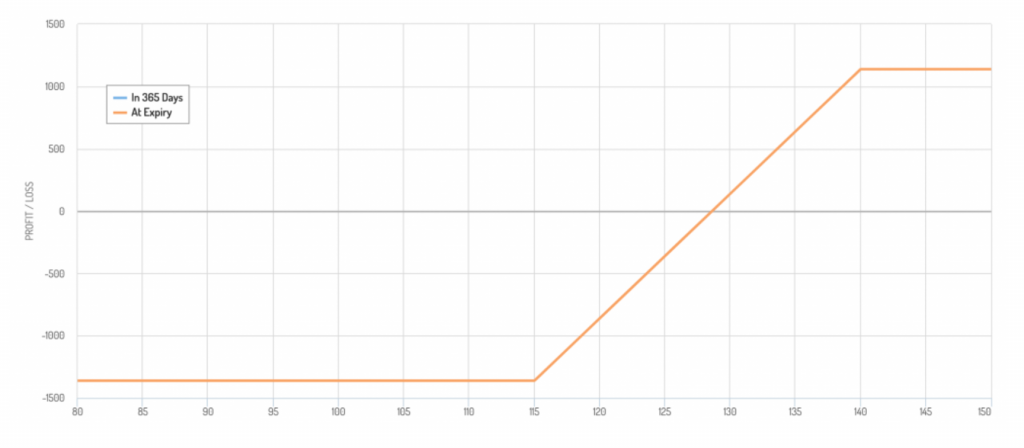

Modified put spread payoff diagram

You might be okay with this trade-off. If it’s a profitable company and the earnings make sense in light of the valuation, that’s not a bad place to be.

If we assume Apple has a forward EPS of $7 per share and trades at $130, that’s a forward P/E of 19x.

If Apple were to fall to $90, this could mean its earnings are expected to decline or there’s a market sell-off due to an unexpected rise in interest rates, markets get out of whack due to liquidity, and so on.

In that case, $7 in EPS would give it a forward P/E of about 13x, or $90 divided by $7.

In other words, at a point you’d consider Apple to be a good value and not be too bothered with not having downside protection.

You could a) think it’s cheap and b) don’t want the additional expense of having a hedge in place.

Moreover, hedging the $90 to $115 range has a high probability distribution associated with it relative to anything to the left of $90 simply because $90-$115 is closer to the current price.

(Source: Interactive Brokers)

4) Collar

As mentioned earlier, a collar involves selling a call option and buying a put option.

The cost of the put option is partially or fully funded by the premium received from the short call.

There’s also more certainty for the trader. It gives you a more defined upside and downside.

If the price of the underlying rises above the call option strike price, the call will result in losses but be offset by gains in the stock.

If the underlying fall below the strike price of the put option, the underlying asset will have losses that are offset by the put option and the premium from the short call option.

So essentially it’s a very price neutral type of structure.

You receive some income to help offset the price of the put from the call.

And you don’t have to suffer large drawdowns in the underlying because of the put option.

To maximize the amount of income received, one could place the short call ATM.

The academic literature has show that the volatility risk premium has a higher Sharpe ratio than the arguably more competitively sought after equity risk premium (ERP).

This gives covered call strategies (and some associated covered call strategies) higher overall Sharpe ratios than standard equity strategies.

It’s also important to note that puts tend to be more expensive than calls in equities.

This is because most people are heavily long stocks and want protection as a form of risk aversion. So they tend to pay more for puts than calls.

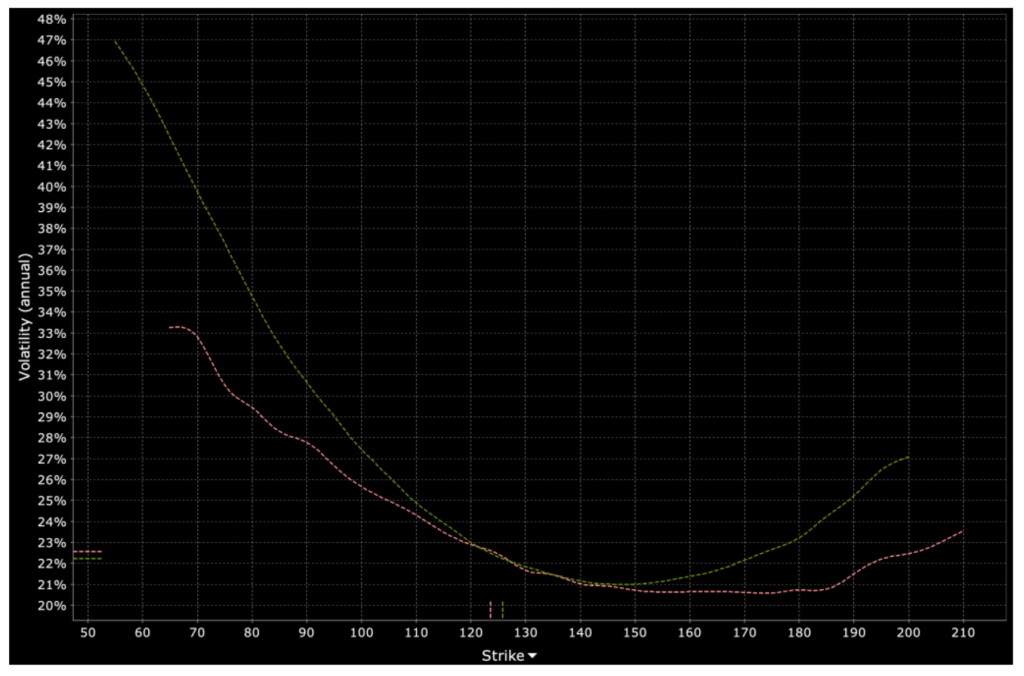

You can see this phenomenon in the volatility skew, which compares the implied volatility of options across a range of strike prices.

The higher the implied volatility the more expensive the option is considered.

Volatility skew in equity options

(Source: Interactive Brokers)

For a 140 call-115 put collar on Apple with a current trading price at $130, the put is slightly further away from ATM ($15 per share away) relative to the call ($10 per share away).

The put is comparatively more expensive because of the higher demand for puts relative to calls in the equity space.

If we look at a payoff diagram, a bullish collar looks like this.

Bullish collar payoff diagram

Read more: Safely Make $50,000 Per Year From One Stock? Exploring the Collar Option Strategy

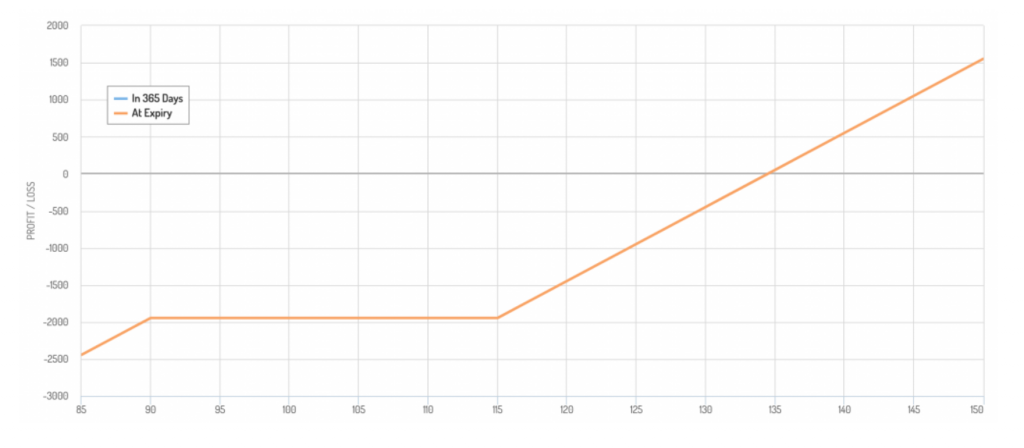

5) Fence

A fence strategy is the combination of a covered call and put spread.

Three options are used in forming a fence in addition to a position in the underlying.

- Long underlying asset

- Short call option (OTM or ATM)

- Long put option (OTM)

- Short put option (OTM) and below the expiry of the other put option

Like the covered call and collar, the fence is a more defensive position. The trader is giving up upside for downside protection.

For a stock, the trader can still get dividend payments running a fence trade structure around the underlying position. The exception is if the call option is ITM and the other party decides to exercise early to claim the dividend.

The fence essentially combines the benefits of the covered call and put spread.

a) Premium from the short call provides income

b) Downside protection from the long put option partially or fully funded by the short call

c) The cost of the trade is reduced further by shorting a put option at a strike somewhere below the first one

A fence is also more of a risk-neutral position, while enabling a trader to still have some price upside, having fairly cheap downside protection (versus just one put) by selling two options instead of being long only one, and giving the trader the ability to still collect any applicable dividends.

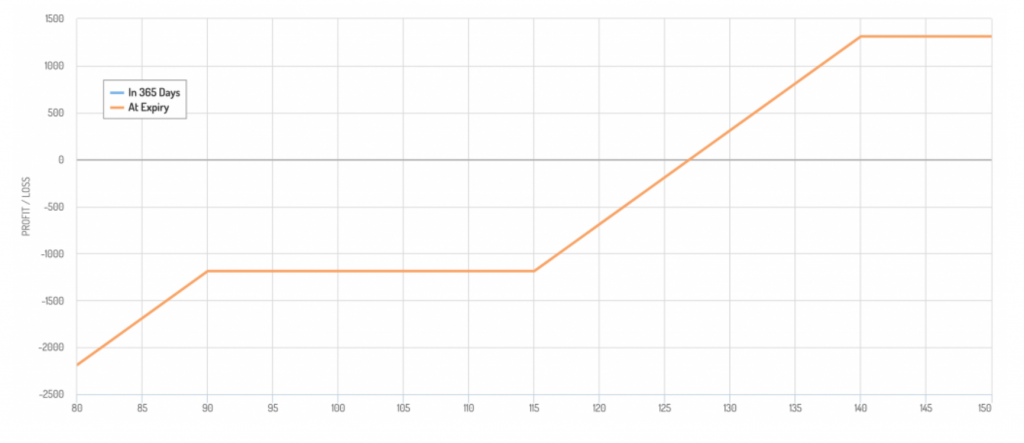

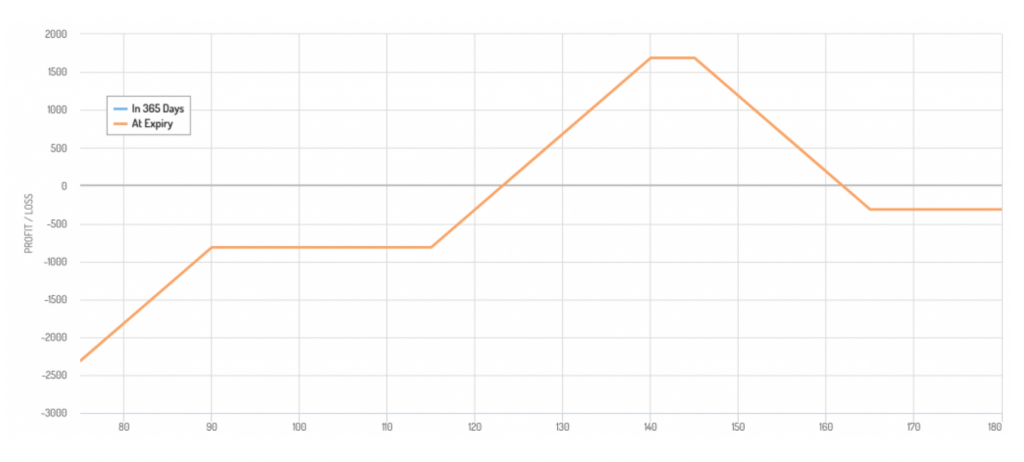

For Apple (AAPL), a short 140 call / long 115 put / short 90 put fence would have a payoff diagram that looks like this:

Fence payoff diagram

You will notice there is left-tail risk from shorting the put.

But everything is about trade-offs and some are more logically acceptable than others. There’s no free lunch.

This article is to simply give you lots of ideas and hopefully expand horizons on how hedging can be thought of from different angles.

As we mentioned in a previous section, a value investor might view going back to a linear position as an acceptable risk because the security has become relatively cheap at that price level.

6) Short selling

Short selling is a basic way to hedge risk associated with being long certain assets.

In trading, the term “delta” is a common term. This means your general exposure to a market.

If you own Apple (AAPL) as-is, then your delta is 1. If you’re short AAPL as-is, then your delta is negative-1.

If you have options surrounding it, then it’s probably somewhere in between, especially if you’re long puts and/or short calls on a long position, or long calls and/or short puts on a short position.

Now let’s say you want to own ExxonMobil stock (XOM). But at the same time you don’t want your portfolio to be too exposed to the price of oil.

Exxon is basically in the business of taking oil out of the ground and selling it. That gives the company a high correlation to the price of oil.

To limit this risk, you could short oil futures or short an oil ETF to hedge some of that risk exposure.

To reduce equity risk in your portfolio, short selling is often the cheapest and most efficient way of hedging out some of your exposure.

If you short cash equities, you also get a cash credit to your account. That can reduce the amount you’re borrowing on margin or give you a positive cash balance, where you might be able to obtain interest.

Borrowing also comes with an associated cost. This can sometimes be high depending on supply and demand.

If there’s large demand relative to the number of available shares, then the cost of shorting will go up. So it’s important to be mindful of the shorting cost itself.

For “easy to borrow” shares, the fee is often 0-2 percent interest per year. That’s often less than the rate of inflation.

For “hard to borrow” shares, the fee can be exorbitant. Basically to the point where it makes short-selling totally infeasible. The interest percent can be in the hundreds or even thousands.

Short selling stocks or futures is a cost-effective way to hedge equity risk.

Futures are favored by many traders to limit the capital commitment.

Some traders may choose to short while also pairing with a short put option.

In a bull market where stock prices are consistently going higher, a trader might want to reduce equity exposure while at the same time writing puts against the short stock positions.

If stocks keep going up, the premium received from the put option will help offset some or all of the losses.

The drawback, of course, is that once the put goes ITM then the short equity exposure no longer serves its purpose as a hedge.

7) Inverse ETFs

Inverse ETFs are another way of getting short, such as being short the S&P 500 or short tech stocks.

Inverse ETFs work by appreciating in price when whatever they’re short declines.

But watch out for leveraged ETFs

But a word of caution on inverse ETFs:

Some of them are leveraged instruments, which makes them poor choices for trading beyond the daily timeframe.

Some traders like leveraged ETFs because it seems like you get more with less – i.e., more hedging capacity for less capital commitment.

But leveraged ETFs come with a decay element.

This is because their values are recalculated every trading day.

They need to be used carefully if going beyond day trading.

Percentages are more important than the value of the index.

For example, if the value of something declines 50 percent, a 100 percent gain is needed to make back the losses. Leveraged ETFs reflect this.

So, for instance, if an index drops from 100 to 99 it loses one percent of its value.

If the index rallies back to 100 the next day that would be a gain of 1.01 percent.

A 2x leveraged ETF of the underlying index would drop 2% from 100 to 98.

The next day, the ETF would rally 2.02 percent to follow the index (2 multiplied by the 1.01 percent gain).

However, following the daily reset, doing the calculation, taking 98 multiplied by 2.02 percent gives us only 99.98.

The more these price movements occur, the more the tracking error is compounded, with higher volatility causing a higher resulting discrepancy between the result you “should have” and the result you’re getting in practice.

Accordingly, there’s a natural decay pattern in these leveraged ETFs. Any holding period longer than one day will distort how effectively they will mirror what it’s supposed to be tracking over the long-term.

If the market falls and you’re long a 2x or 3x leveraged short ETF, you will make money in excess of simply being short a straight inverse ETF with no leverage.

But it won’t be the 3x many might assume they’ll be getting unless the holding period is limited to intra-day only.

The silver lining on leveraged ETFs

The advantage of these securities, however, is that they can be traded in a regular stock trading account, as some traders don’t have access to futures and options with the limitations that are often placed on them.

They are okay for pure day traders.

With that said, the leveraged varieties should ideally be avoided for those who have time horizons beyond one day because of the tracking error associated with them.

8) Owning volatility

When stocks lose value, there are generally large spikes in volatility in the market. This makes the idea of owning volatility attractive.

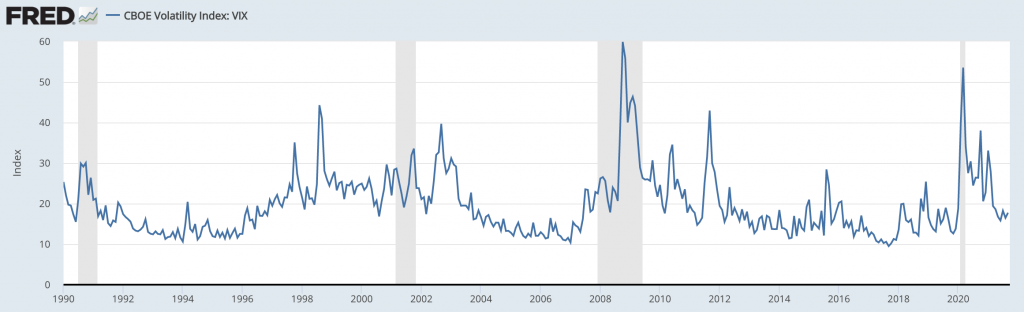

VIX is the most popular volatility index, established in January 1990 by the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE).

This happened most notably in:

- 1997 (Asian balance of payments crisis)

- 1998 (Russian default, LTCM)

- early 2000s (tech bubble crash)

- 2008 (financial crisis), and

CBOE Volatility (VIX) Index: January 1990-Present

(Source: Chicago Board Options Exchange)

Owning volatility was a good way to hedge equities.

The VIX index is essentially an index on the implied volatility of various options within the S&P 500.

In turn, there are futures, and options and ETFs based on those futures.

When stocks drop in value they generally gain.

Volatility is nonetheless one of those products that tends to lose value as time goes on.

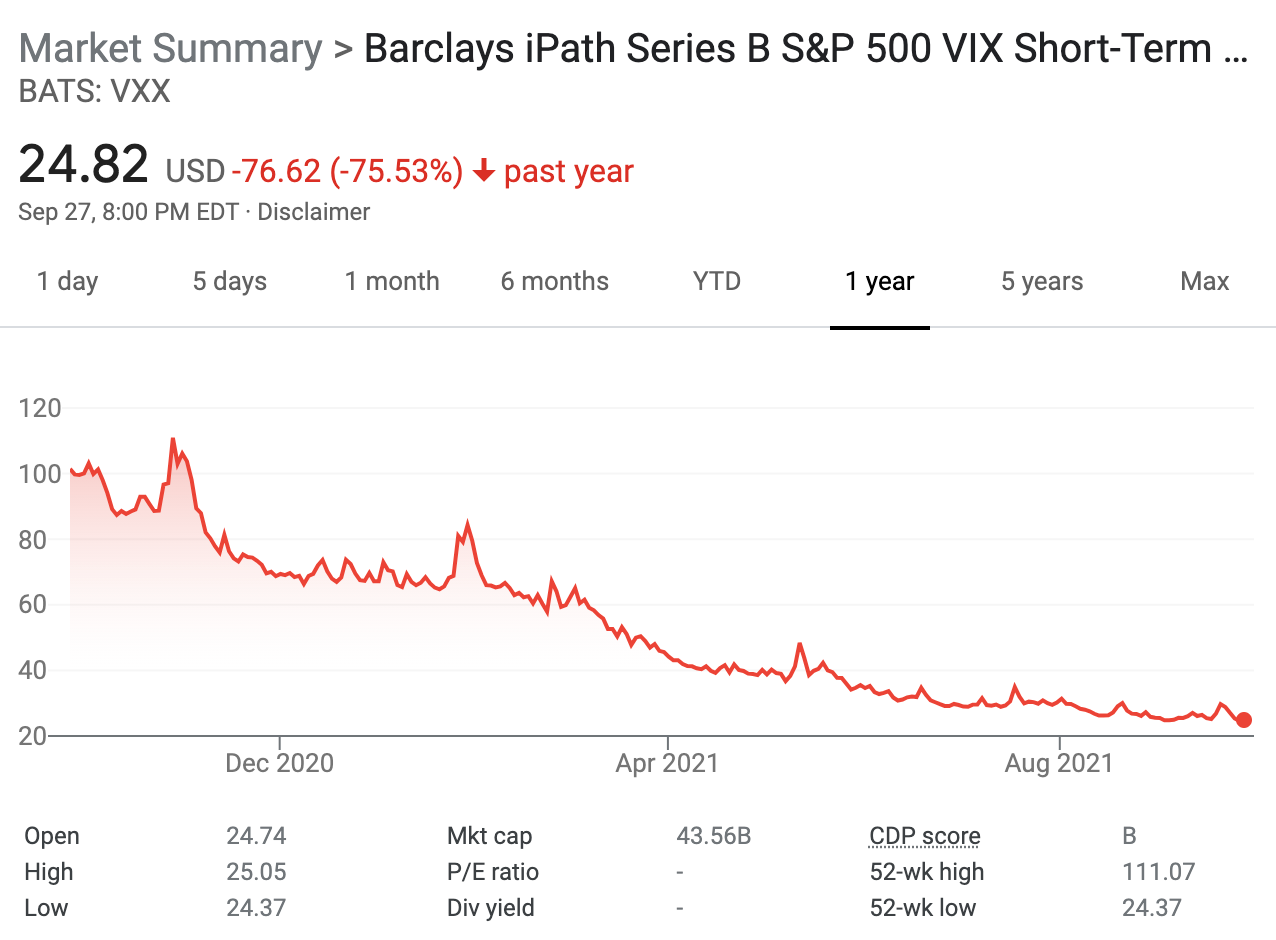

The VXX ETF is well-known in this way, being tied to the VIX index.

Though these volatility products tend to slowly lose value, the nature is such that they can gain in value in a big way when there’s a risk-off event in the market.

Volatility through options

Volatility is also a part of regular vanilla options. Holding all else equal, options gain in value when volatility increases.

But options are not a pure volatility product because of the delta component (i.e., movement of the underlying) and theta component (i.e., time decay).

Volatility swaps are a type of exotic option that serves as a pure volatility product, but they’re available only to institutional investors.

9) Diversifying

Diversifying well will improve your return relative to your risk better than anything else you can practically do.

This is because different types of assets and asset classes have different environmental biases. Therefore they will act differently.

When stocks decline, there are generally other assets or trades you can put on that will help increase in value to help offset these losses.

This can include owning the following types of assets:

- Nominal rate bonds

- Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

- Gold

- Commodities

- Certain currencies

- Volatility

- Privately held assets that can keep providing you income (e.g., real estate, certain digital assets)

- Liquid alternatives, and so forth

Balancing your assets well will reduce your overall drawdowns, give you shorter underwater periods, lower left-tail risk, among a host of other benefits.

We have other articles dedicated to the idea of diversification and how to build a good overall portfolio.

- How To Build A Balanced Portfolio

- Building a Balanced Portfolio with Options

- Building a Balanced Portfolio with VRP Overlay

- Balanced Beta: Efficiently Balancing Risk, Not Capital

- Simple Portfolios: Improving Outcomes by Simplifying

- The Barbell Portfolio Strategy

- How to Improve Risk-Adjusted Returns

10) Reducing your position size

As discussed a bit earlier, owning too much of something increases your risk. And it tends to do so in a non-linear way. It also increases the necessity to hedge.

If something is 60 percent of your portfolio, such as stocks in a 60/40 portfolio, then there’s a greater risk of that blowing a large hole in your portfolio.

If stocks decline by 50 percent and bonds climb by only 10 percent, you’ve still lost over 25 percent of your portfolio. And bonds don’t always diversify stocks, especially in a super-low rate environment.

The risk is even worse when assets are bought on leverage.

With instruments like futures, some ETFs, and having easy access to margin borrowing, it’s fairly straightforward to make just one asset more than the entire size of your portfolio in a few simple clicks.

Position sizing is a part of prudent risk management.

In financial markets, the range of knowns is typically not very high relative to what you don’t know and can’t know relative to what’s discounted in the price.

This is particularly true for things with structurally high volatility like stocks.

Nonetheless, limiting position sizes within individual securities is not enough, given the high correlation among stocks.

Even the S&P 500, which typically houses around 500 different securities, has large drawdowns despite its “diversified” nature.

Hedging equity risk can be more effectively done when diversifying not just by different stocks, but different asset classes, different countries, and different currencies.

11) Cash

You can hold cash against something to make it less volatile. Cash provides a buffer against adverse events.

At the same time, you don’t want too much. Cash seems safe because it doesn’t have much volatility to it.

However, cash loses value over time because of inflation and the taxes that have to be paid on interest. The inflation rate might be just 2-3 percent per year in many countries. But that makes a lot of difference over time.

Also, in developed markets, cash doesn’t have any yield at all, or even a negative yield, so there’s no direct investment return.

Central banks are going to target an inflation rate of at least zero – they’re always going to want to avoid deflation – so people will be incentivized to make purchases of real goods and services and invest their money so it doesn’t lose its value over time.

Nonetheless, everybody needs some level of cash.

Owning some cash is necessary to have some level of liquidity and optionality, and avoiding margin calls, which tend to force you to sell at the worst times.

Cash enables you to take advantage of those times when there’s a large decline in asset prices because of all of those who have to sell in order to raise cash when they know they should ideally be buying.

12) Buying a call option

Call options aren’t really a hedge, per se, on their own – unless you’re hedging a short position. But they do hedge against left-tail outcomes.

For example, let’s say you own a stock at $100 per share and you buy 100 shares.

That’s $10,000 worth of potential risk you have at stake. If the company ultimately isn’t worth anything, then there’s the risk of losing all of your investment.

On the other hand, if you were to buy a 100-strike call on the stock, your risk would be limited to the premium.

You would have a little bit of downside but all the upside.

Call option payoff diagram

You can, of course, cheapen the cost of a call option by integrating with other strategies discussed above (e.g., collar strategy).

Choosing the best hedge

Concentrated portfolios are likely going to require hedges that are larger and therefore more expensive relative to those that are diversified well.

If a trader has equity exposure that’s equal to 4x the total net liquidation value of their portfolio, they have much greater risk to bear from a decline in equities relative to someone with 30 percent of their portfolio in stocks and the remainder that’s diversified in other asset classes.

The trader that runs a more concentrated portfolio could use a larger hedge to get down on the high left-tail risk while a more diversified trader already has a reasonably well-hedged portfolio and won’t have to bear those types of costs.

There are trade-offs with everything.

For many traders, investors, and those with retirement accounts, most of their money is in stocks.

Because of this concentration risk, they’re probably going to want to hedge some of it to cut down on this risk in some way.

This is why many portfolios shift more toward bonds as someone gets closer to retirement and necessarily has to be more risk-averse.

If someone has a very long time horizon, a 20 percent or more drop in the stock market isn’t going to be as concerning as someone who is nearing retirement age.

Losing 20 percent or more of your net worth when you’re 25 is much different relative to someone who loses this amount right before retirement.

It also depends on what kind of portfolio.

The NASDAQ would be a pretty accurate representation of your portfolio if you invest in many US-based technology companies.

For someone who invests in a variety of larger cap companies the S&P 500 could be a better match for the portfolio.

Portfolios that have more overall volatility and a higher beta will necessitate larger hedges.

And there are the various types of hedges and those trade-offs to consider.

Put options, as mentioned, tend to be expensive even though they will be effective at limiting your loss beyond a certain point.

You can limit some of this cost by selling call options on your securities at a level you’d be comfortable selling them. But that will limit your potential upside.

Forming a collar on your position will give you a defined upside and downside and is popular for more concentrated portfolio holdings.

Selling a put option below your long put (forming a “fence”) can cheapen hedging costs further. But it will subject you to further downside if price gets down to that level. Nonetheless, that may be a point at which you might consider the security cheap anyway, so taking that risk may be worth it to you.

You can short sell stocks (i.e., cash equities) or stock futures as a more direct way to hedge without having to pay premium. But it can limit your returns.

Once you have an idea of what kind of hedge could be best for your portfolio and overall goals, you will need to make some basic calculations:

- What is your upside? Will it be unconstrained, or will it be capped (e.g., due to a short call)?

- What is your downside? Will it be capped (e.g., with a long put) or just limited?

- How much will it cost?

There are ways to hedge that don’t necessarily have to explicitly incur a cost – such as the covered call, collar, fence.

And when you hedge, does that mean the entire position or just part of it?

But you will need to understand whether those trade-offs – e.g., constrained upside – make sense for you personally and what kind of protection they provide.

The costs of hedging a retirement portfolio

If you’re buying options to hedge that involves paying premiums.

These premiums depend on several variables, including:

- price of the underlying

- implied volatility

- strike price

- time to expiry

- interest rates

- dividend (if applicable)

The cost to hedge your entire position – i.e., an ATM put (or call in the case of a short position) – is the most expensive.

For a stock like AAPL, hedging your entire position ATM (or the expiry as close to ATM as possible) for one year will cost somewhere around 10 percent of your total position.

AAPL is not a stock that can be expected to make 10 percent per year in perpetuity between dividends and capital gains, given its nature as a maturing company.

It’s not easy to grow a large company’s earnings by 10 percent per year. And declining interest rates won’t be a perpetual tailwind for stocks.

So it can be difficult to justify the cost of a plain ATM put option. The cost of the hedge will likely swamp the sum of your capital gains and dividends over the long run.

Accordingly, traders typically like to hedge with OTM puts. These don’t provide as much protection because you’ll have to take some losses before they kick in fully – if they ever do.

But OTM puts come with the principal advantage that they’re cheaper. They can also serve their purpose as protection to avoid a large decline in the asset.

And OTM puts can be mixed in with other strategies to cheapen their cost.

i) You might consider selling a put somewhere below your long put. This means your hedge would “roll off” at some point. But it might be a suitable trade-off if the security is sufficiently depressed in price.

ii) You can sell a call against your open long positions. For example, let’s say you own stocks in a pricey market (i.e., earnings multiples are elevated by historical standards, among other measures).

If you own a stock at $70 per share and would be happy to sell if it rose about 10 percent, you could consider selling a call option somewhere around $75 or $80. If it doesn’t get to that price, you were able to collect additional income from the premium.

And of course the stock could also rocket higher to $100 per share (or whatever). So you might be kicking yourself if you sold a call at $75 or $80. But if you felt that’s where it’s priced well enough to sell, there’s no harm in that. And it’s always better than losing money.

iii) You could sell multiple call options – essentially be overweight calls. This gives more hedging effect than just being short calls equal to the position.

For example, let’s say the stock you own is trading at $70 (100 shares) and you decide to sell one 75 call and one 80 call. If the stock rises to $80, you’d have to buy an additional 100 shares to hedge, otherwise you would start losing money.

The main risk is that the security rises quickly and you’re not able to dynamically hedge on time. Stocks can easily rise and fall 20 percent or more overnight, and stock markets are only open for a portion of the day.

iv) Going off the above strategy, you can consider overweighting your short call exposure to take advantage of the extra premium.

This means you could actually see less profit if the stock went above a certain level.

For example, for AAPL trading at $130, you could sell a 140 call and 145 call, in addition to being long a 115 put, sell a 90 put, while also being long a 165 call to cap risk if the stock appreciates materially.

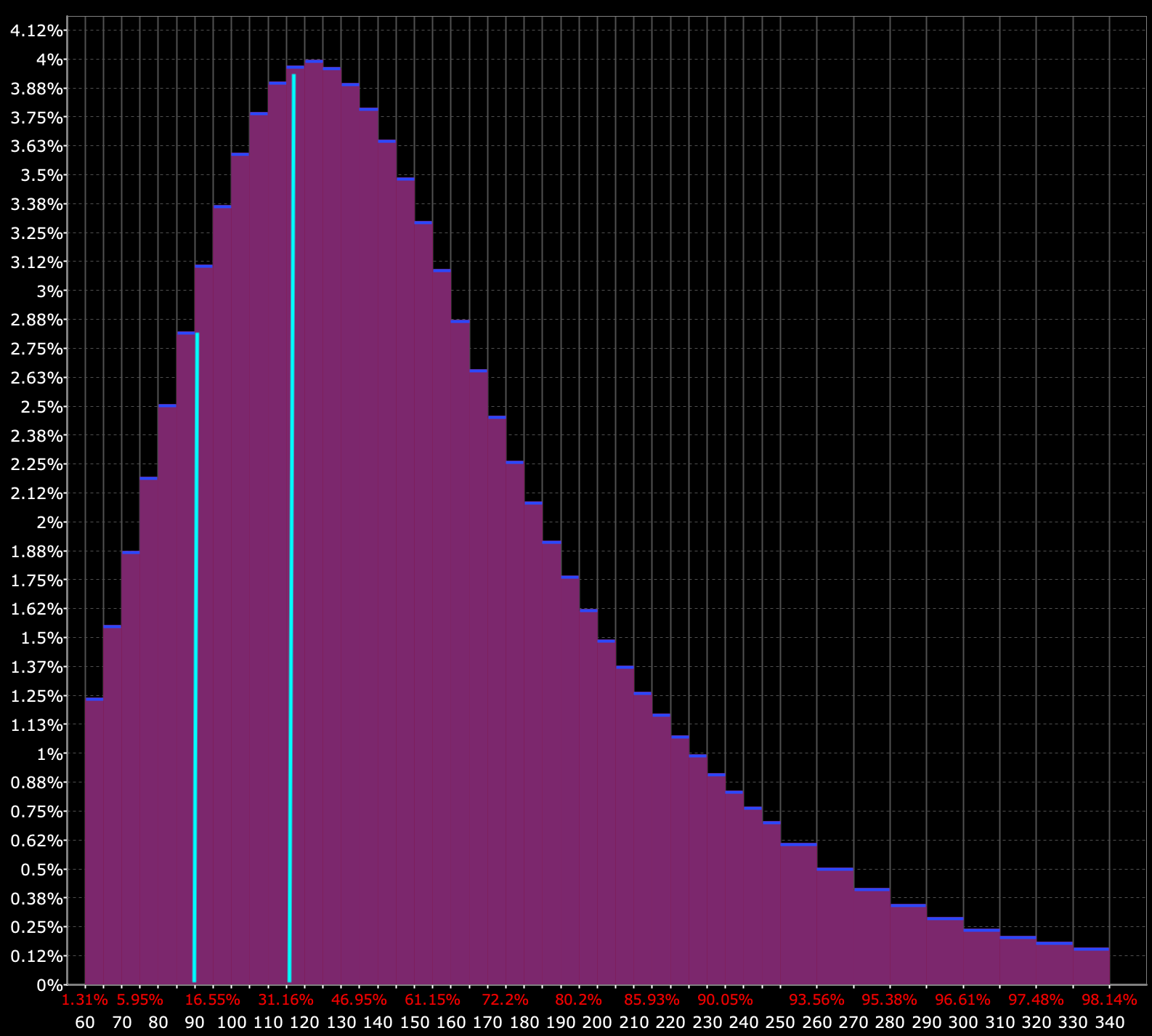

Your payoff diagram would look like this:

It effectively looks like a modified form of a strangle. At the same time, you still see a nice profit area and the extra call premium helps to reduce your losses should the security decline in value.

Conclusion

In this article, we included the following as possible ways to hedge equity risk:

- Long puts

- Put spread

- Covered call

- Collar

- Fence/Dutch rudder

- Short selling

- Diversification

- Cash

- Owning volatility

- Inverse ETFs

- Reducing position size

When you trade the markets there will always be risk, so it’s impossible to eliminate risk entirely.

At the same time, it’s important to control the main risks and not have them at an unacceptable level.

If you’re involved with trading for long enough, you’ll understand that a lot of learning how to hedge risk will come from experience.

If risk isn’t taken seriously or what you’re doing isn’t understood very well it’s virtually impossible to have any type of sustained success.

While risk can never be avoided completely, it’s possible to eliminate the risk of big losses.

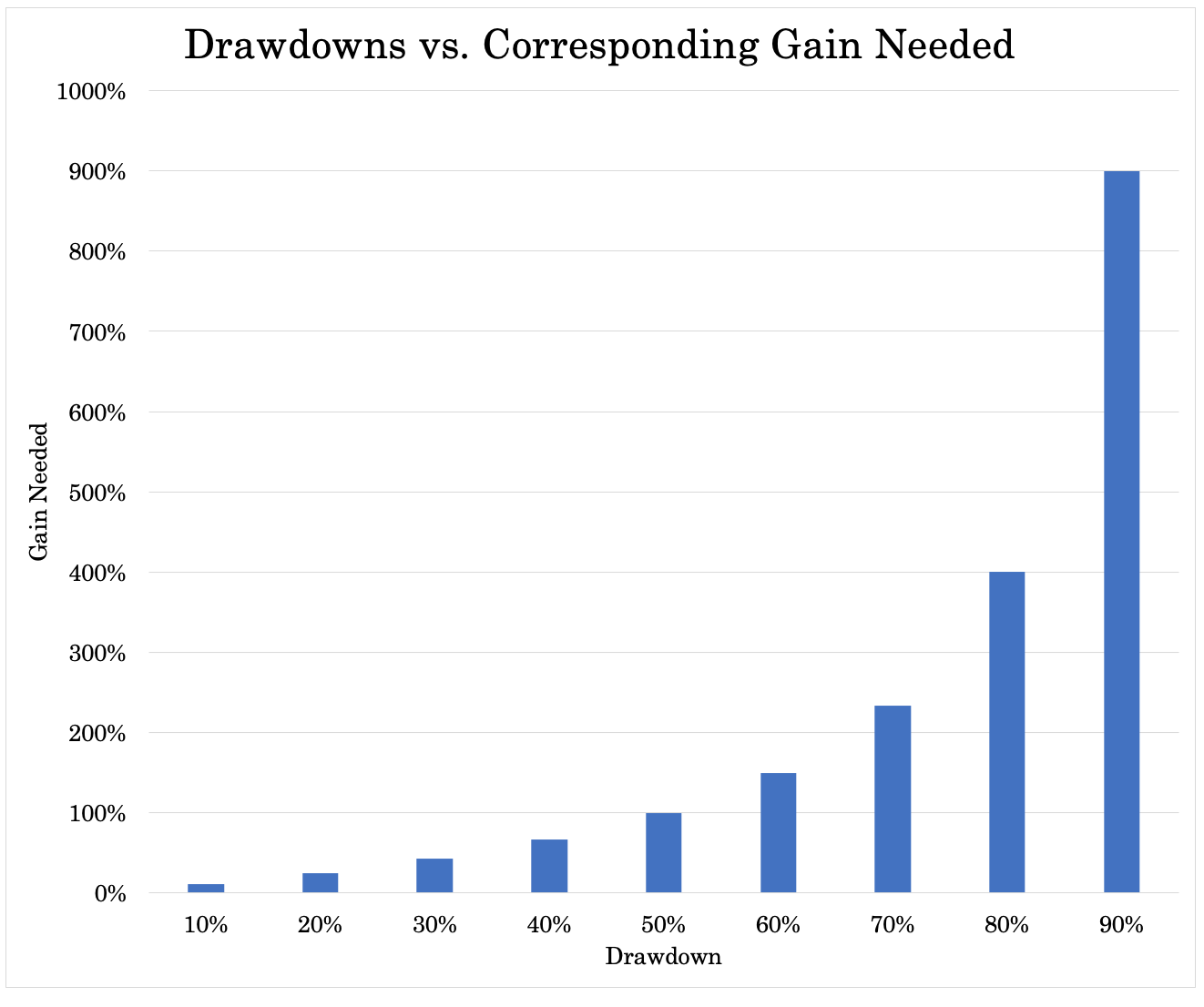

Whatever you do, it’s essential to avoid big drawdowns. They’re very difficult to recover from. Some are impossible to recover from and you’ll have to make the money back another way.

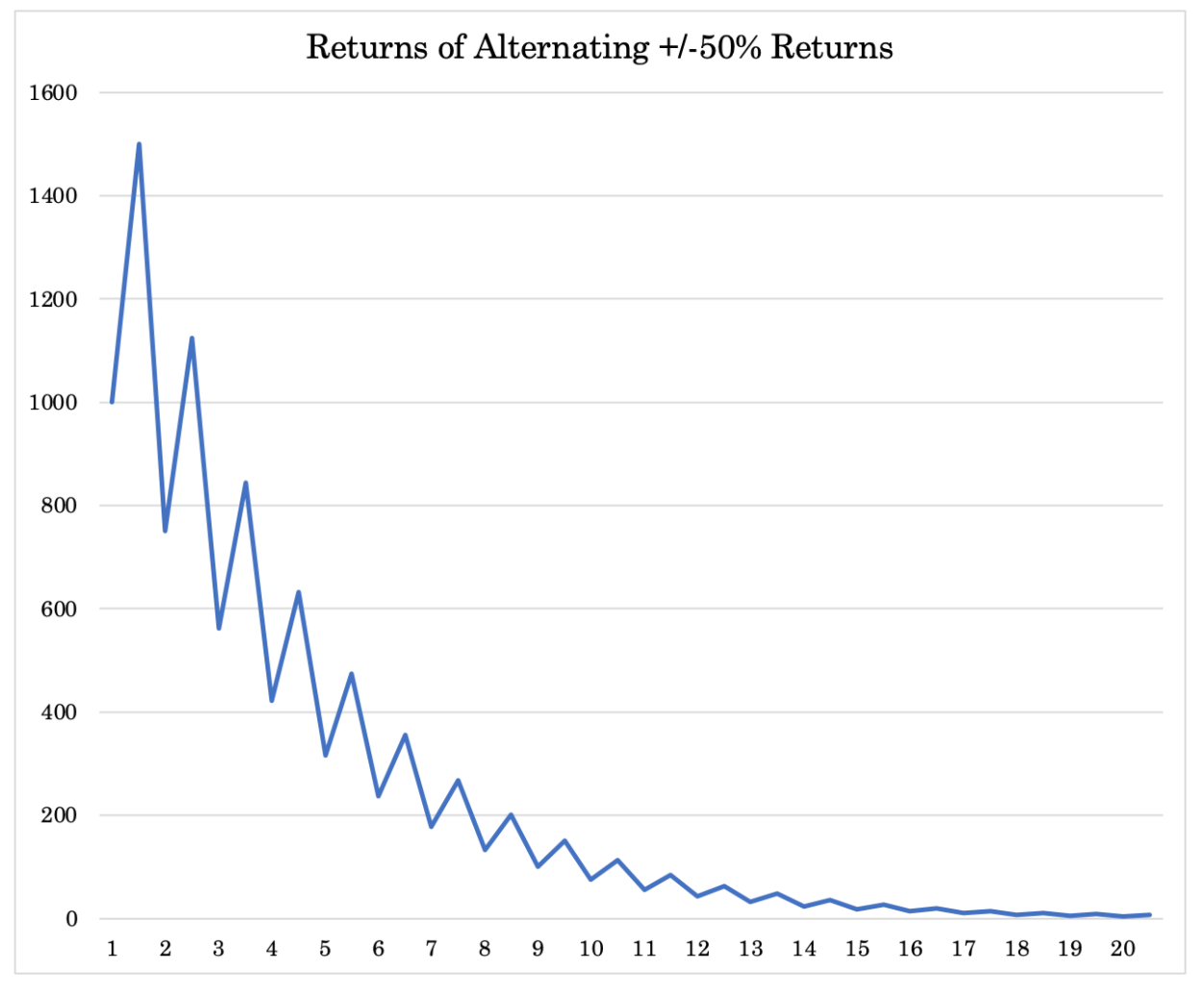

If you drawdown 50 percent, you need a 100 percent gain to get back to breakeven. The larger the loss, the greater the gain needed in a non-linear way.

If you play a game where you alternate equal percent wins and equal percent losses, you’ll eventually run out of money.

Example

For instance, let’s say you have alternating gains and losses of 50 percent each.

And say you start out with $1,000.

You gain 50 percent in the iteration (you’re now at $1,500) and lose 50 percent to end the round (down to $750).

Then in round two, you gain 50 percent (up to $1,125), lose 50 percent ($562.50), and so on.

Each round of this game that you go through, you’ll have less money.

To pay off that 50 percent loss, you need a 100 percent gain, not just the corresponding loss.

Your 50 percent gain simply isn’t anywhere near enough even though it’s the same magnitude.

At the start of the fourth round – three wins and three losses – you’ll already be down more than 50 percent of your original investment at just above $00.

After just ten rounds of this game, you’ll have lost about 90 percent of your original investment.

After 15 rounds, you’ll be down more than 97 percent.

And after 20 rounds, you’ll be down more than 99 percent – to just $6 left of your original $1,000.

Graphically the results look as follows:

The basic idea is that you have to have a keen eye for risk management. It’s the most important aspect of trading and of most business activities.

The strategies considered in this article can help traders maintain the kind of upside they want while avoiding the risk of having unacceptable downside.