Building a Balanced Portfolio with Options

Market participants are always looking to maximize their reward relative to their risk. One of the best ways to have the big upside without having the unacceptable downside is through the efficient use of options and derivatives. In this article, we’ll go through building a balanced portfolio with options.

Options can provide leveraged returns with fixed downside. When used in a thoughtful way, options give you convexity.

In traditional portfolios, getting a certain target percent annual returns in your portfolio can be as simple as finding an asset that gives you X percent per year and levering it up to give the desired return on equity.

The downside of that is the leverage you employ gives a very large risk of steep drawdowns or even wiping you out altogether.

Efficiently using options

Efficient option construction enables you to position your portfolio to specifically capture the part of the distribution of returns you want. At the same time, you can set your risk within a predefined limit or boundaries.

If you own an option, you transfer any risk associated with that part of the distribution to a counterparty. In exchange, you pay a premium.

That premium, of course, can be expensive.

Similar to private insurance companies, those who sell financial market insurance command a premium in order to incentivize them to take on this risk.

The margin options sellers have, associated with the practice of selling financial insurance, is called the volatility risk premium.

Being on the short side of an option contract often entails fixed upside with unlimited downside. That’s not good unless appropriately hedged.

That gives a type of convexity to the buyer. It’s essentially a type of leverage.

That’s a good thing, but it has to be approached appropriately.

The buyer has to keep in mind that the volatility risk premium is expensive on net. If you randomly select a bunch of options, you should expect to lose money on average.

There are not only commissions but also the spread to contend with. Options markets are traditionally much less liquid than the underlying market. Some options markets are so illiquid it makes them nearly impossible to transact in, at least in a way conducive to good returns.

Not every market is SPY or AAPL with ample amounts of liquidity.

Generally speaking, the further out-of-the-money (OTM) an option is and the longer the maturity, the more illiquid that particular market is likely to be (i.e., call or put at any given strike price at any given maturity).

Moreover, if you’re paying for simply plain vanilla options, you may not always be setting up a trade in the most efficient way.

At the institutional level, there are certain features associated with exotic options that can help buyers reduce their costs – e.g., one-touch, knockouts, reverse knockouts, digitals / binary options.

But, as a whole, efficiently constructing vanilla options is certainly a perfectly valid path for:

a) not only reducing options costs, but also

b) capturing a more specific part of the distribution that you’re aiming for.

Steps to Building a Balanced Portfolio with Options

In constructing a portfolio, there’s generally a three-step process:

i) Asset allocation

First, you need to know what your strategic asset allocation is. It should be something that maximizes reward per unit of risk.

Diversifying well is going to do a better job of this than any given investment. This is because you can take advantage of the fact that asset classes act differently from each other.

Each asset class, no matter what it is (e.g., stocks, bonds, gold, oil), is going to drawdown 50-80 percent during the course of one’s lifetime. Environments that are good for some asset classes will be bad for others.

We show the mathematical reasons why diversification is critical in a separate article.

If you do the allocation part well, which is the most important step, this gives you a convex outcome on its own. Namely, it has a lot more upside than downside.

ii) Trade structuring

Adding any additional layers of convexity is the second step.

You take your asset allocation, which should be convex on its own, and make it even more so.

This is where thoughtful trade structuring comes in.

iii) Risk management

Risk management adds another layer where you actively manage your portfolio to an extent.

All portfolios – whether they have a day trading focus or are more geared to buy-and-hold over decades – require some level of risk management.

It might mean managing daily on a continuous basis or it could mean rebalancing once a quarter or once a year (for example), depending on the focus.

Asset allocation

We’ve gone over this in depth in other articles, including better allocation within single asset classes (e.g., stocks), so we’ll defer to that thinking.

But generally, if you’re trying to build some type of balanced or risk parity portfolio, you’re going to try to have an allocation that can do well through all environments.

That means diversification among:

a) asset classes

How much do you allocate toward stocks, nominal rate bonds, inflation-linked bonds, gold, commodities, and so on?

b) countries

You have basically three main spheres of global investing.

How much do you allocate toward the US and other reserve currency countries (e.g., developed Europe, Japan)?

How much do you allocate toward large and growing economies like China and India?

How much do you allocate toward cyclical emerging markets?

c) currencies

Most individual traders and investors don’t think about diversifying their currency exposure. If they’re US-based, they’re generally all in dollars. If the eurozone, then almost all in euros, and so forth.

Currency diversification also includes gold, which can be useful in lots of portfolios in something around a 10 percent allocation.

Gold functions closer to a currency than it does a traditional commodity subject to supply and demand based on the consumption of it. It’s a non-fiat, non-credit dependent, long-duration store of wealth asset that makes sense to have, just not in a too high or too low allocation.

Currency diversification is underutilized in most investors’ portfolios, but is important to ensure their real purchasing power isn’t hit over time. Though devaluations of currencies help asset prices, increases related to currency effects are in nominal terms.

For more on the thinking of how to build a balanced portfolio – including takes on the 60/40 portfolio, how to protect against inflation and stagflation environments, general post-crisis investing, and more, we have a lot of it below.

Investing in a Zero Interest Rate Environment

Stagflation: How It Occurs And Building a ‘Stagflation Portfolio’

4 Alternatives to Bonds (and Cash)

Simple Portfolios: Improving Outcomes by Simplifying

Trade structuring

So, you have an asset allocation you’re happy with. Now you need to figure out how to structure those ideas.

Doing standard trades in the underlying can be fine. For those who need to deploy lots of capital, like institutional managers, they will be stuck doing a lot of linear, delta-one type trades where they buy the underlying asset (e.g., SPY, AAPL).

Options can also be part of it or even the entire portfolio.

It’s just important to keep an eye on costs.

If you use standard vanilla options, especially in less liquid markets or securities, what you’re paying for the premium plus transaction costs (i.e., the spread between the bid and ask) can be a lot.

You should always look for trade structures that will limit your costs while also capturing the part of the distribution of potential outcomes you’d prefer.

Risk management

Risk management pertains to managing positions once they’re on.

If you have a balanced portfolio structure, your primary concern is largely going to be in maintaining that balance.

For example, if stocks do well, but bonds and gold do less well, you might sell off a proportional amount of stocks and put it into the lower-performing assets as a way to maintain that diversification.

If you have tactical trades within that structure, risk managing those will be part of it.

__

For purposes of this article, we are focusing on the trade structuring part.

How to reduce the cost of options

Options are great to get the kind of high potential return you’re looking for. But you don’t want to pay too much otherwise there’s a good chance you’ll be materially eating into your potential returns.

We’ll go through the main ways to reduce your options costs:

I) Pick liquid markets

If the spread is wide in the market you’re targeting, you’re already at a big disadvantage.

It’s not uncommon to enter a trade in an illiquid options market and already be down five percent or more just from the size of the spread between the bid and ask price.

Then if you need to get out of a trade, you have the same issue. Your transaction costs are going to be very high. This becomes worse in a non-linear way the larger the trade size because of the influence it has in moving markets.

That means you’re going to need to stick with mostly liquid markets in what you’re trading.

II) Choosing a further out-of-the-money (OTM) strike price

When you choose a strike price that’s further from the spot price, you decrease the probability of the option landing in-the-money (ITM).

At the same time, you reduce how much you can lose.

Moreover, because the premium you pay is less, this can also amplify your effective leverage on the trade.

Example

Say the price of something you want to buy is $90. You want to be long through the options market to limit your downside.

The price of a 90 strike call on an option expiring in six months is $1,300 per contract.

The price of a 100 strike call expiring in six months is $900 per contract.

The 90 strike call is more likely to be ITM by expiration by virtue of the fact that it’s at-the-money (ATM) currently.

The 100 call is less likely because it’s OTM.

However, by expiration, on a percentage gain basis, if the underlying goes sufficiently ITM, you can make more on the 100 strike than the 90 strike.

The 100 strike’s lower price can help create more leverage, in effect.

Let’s say the price is $110 by expiration:

On the 90 call, you make $2,000 minus $1,300, or $700 total.

On the 100 call, you make $1,000 minus $900, or $100 total.

If the price is $130 by expiration:

On the 90 call, you make $4,000 for an initial $1,300 investment, a little more than 3x.

On the 100 call, you make $3,000 for an initial $900, or about the same ratio-wise.

But if it’s $150 by expiration:

The money-on-money multiple goes up to 4.6x (for 90 strike) and 5.6x (for 100 strike).

Of course, this leverage effect gets more amplified on the way up.

$200 by expiration would yield an 8.5x return for the 90 strike and an 11.1x return for 100 strike.

Keeping important trade-offs in mind

Options is entirely a game of trade-offs.

If you want a further OTM option, you are sacrificing the probability of landing ITM for higher money-on-money upside since you pay a lower premium.

If you want something closer to ATM (or even ITM), you are increasing your probability of landing ITM but lower your potential money-on-money upside given the higher premium.

III) Choose a closer maturity

Options that are closer to maturity are going to be cheaper than ones further out.

This is self-explanatory because less time to expiration means less “action” can happen relative to a longer-maturity option. So, options sellers don’t need as much compensation for bearing this risk.

This is similar to the concept of duration. Higher duration assets typically have higher risk premiums associated with them because of the greater interest rate risk and/or credit risk.

IV) Choose “underpriced” options

This is nonspecific and generally the least actionable, but it’s one possibility.

Generally speaking, in options markets, buyers “win” when realized volatility is in excess of implied volatility. Sellers come out ahead when realized volatility is below implied volatility.

Therefore, options buyers ideally buy when implied volatility levels are lower than anticipated volatility.

For example, the S&P 500 generally has volatility of around 15 percent annualized over the long term.

If you see the implied volatility of an S&P 500 product (e.g., SPY ETF, ES futures) trading at an implied volatility of 10 percent, it could be underpriced.

Of course, the market prices everything for a reason. And the past is not a very good predictor of the future in the financial markets.

But in some cases, markets do extrapolate the past to a point where something becomes too cheap or too expensive relative to its long-run equilibrium.

(Note: It’s difficult to time markets, so you can suffer losses in the interim relative to when markets reach these anticipated equilibriums, if ever.)

An example would be the pricing of volatility in early 2018. People extrapolated the past and built up a lot of short vol exposure and leveraged their trades.

When volatility is low, yield becomes the more important factor. Risk premiums decline, asset prices increase, and people are more inclined to leverage to get the returns they want.

But this build-up of leverage in the system can sow the seeds of its own demise. When a catalyst occurs to send the market in the other direction, the leverage exacerbates the drop.

Those betting on higher volatility, seeing the current state of the market as unsustainable, would have seen losses for a long time.

In February 2018, better than expected wage growth in the US caused the market to anticipate that the Fed would tighten faster than was discounted in the term structure of interest rates. This caused a correction in the stock market and much higher volatility than was previously extrapolated.

V) Using spreads and prudently working the short side

We covered factors on the buy side of the equation. You can also use the sell side to increase your reward relative to your risk as well.

When you buy a call option and short a call option (further OTM), this helps reduce your costs (from the premium received by being short) and creates what’s called a spread.

A bull call spread looks like a collar.

Selling options in an incautious way can be disastrous, so it’s important to do things well.

If you choose to sell options, there are the standard hedging techniques such as the covered call, covered put, delta hedging, and so on.

In a pure options portfolio, however, you hedge your downside by being long corresponding options. The option that you buy effectively covers the short option.

Example

In our previous example, let’s say the underlying is $90 and you want to be long, so you buy a 100 strike call out six months.

The cost is $900. You figure that even if whatever you’re buying moves up to $110, you only make $100 per contract ($110 minus $100, with 100 shares per contract ($1,000) minus the $900 premium).

That $100 is not much considering you were on the right side of the trade and had a sizable move. Your profit is limited because options are inherently expensive.

So to whittle down your cost, you can do a few different things:

a) Sell a call further OTM

If the price is $90, your long call has a 100 strike (and costs $900), you can reduce the cost of your long options trade by selling a call somewhere beyond the 100 strike.

You have a trade-off to make between how much upside you want and how much you want to reduce the cost of your trade.

You might believe selling a 120 call would be a quality middle ground. The 120 call, in this case, would be $470 per contract. If you sell this, you get a credit. Namely, someone pays you that premium.

That would mean your net outlay goes from $900 down to just $430 (the $900 cost of the call minus the $470 credit from selling the call).

So your new trade is essentially $2,000 of upside since the 120 call would offset the 100 call if the former were to go ITM.

And your new cost goes from $900 down to $430.

Some traders might want to have the unlimited upside associated with just the plain vanilla call and be okay with paying for it all.

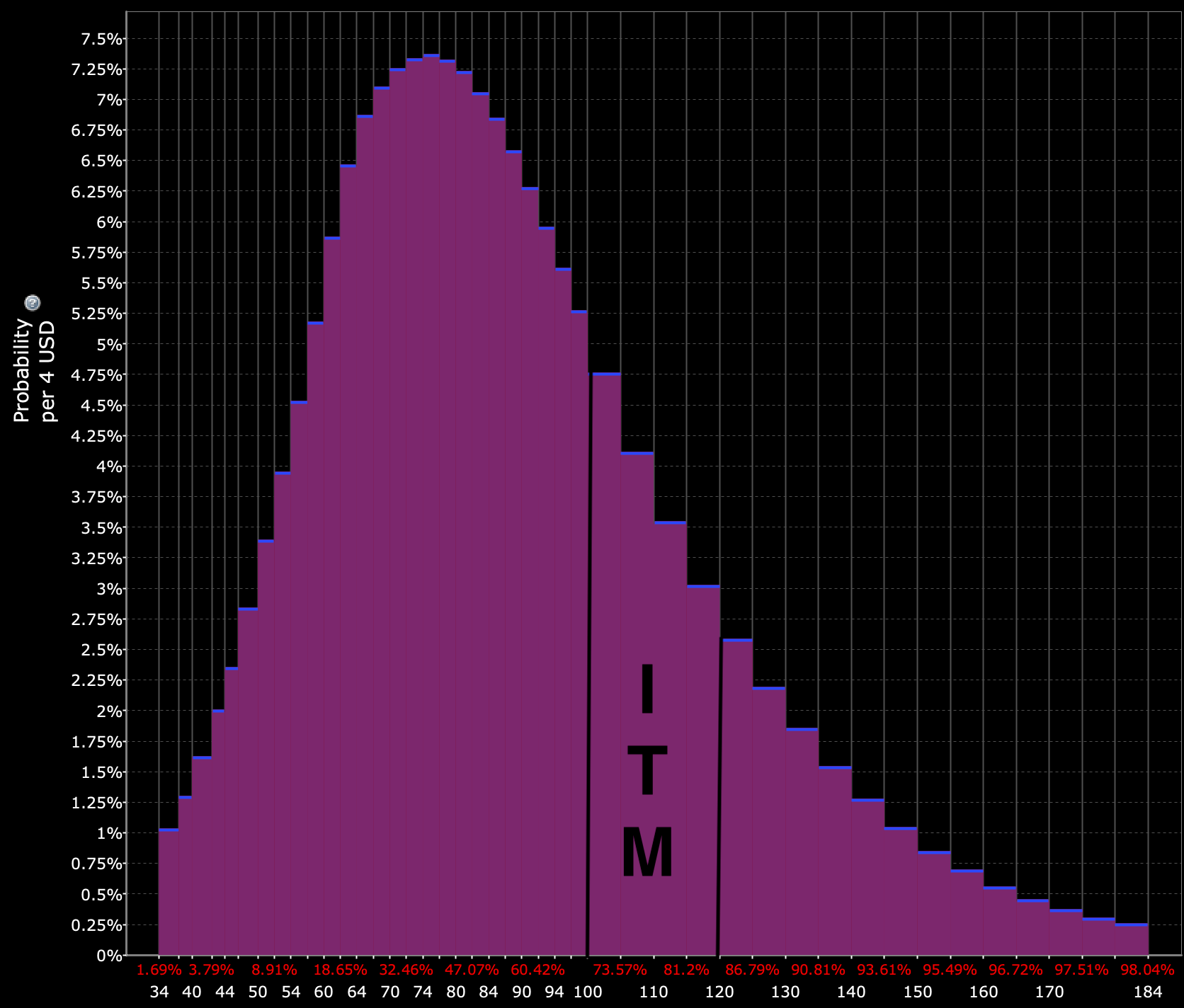

At the same time, it’s also important to keep in mind that the $100-$120 range is in a fairly meaty part of the distribution (since it’s relatively close to the spot price), more so than any equivalent interval above $120, which is starting to get into the tail.

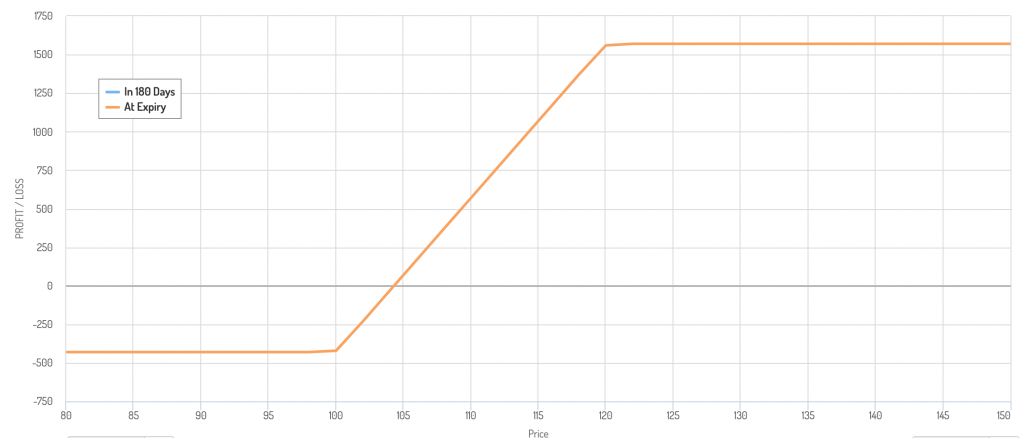

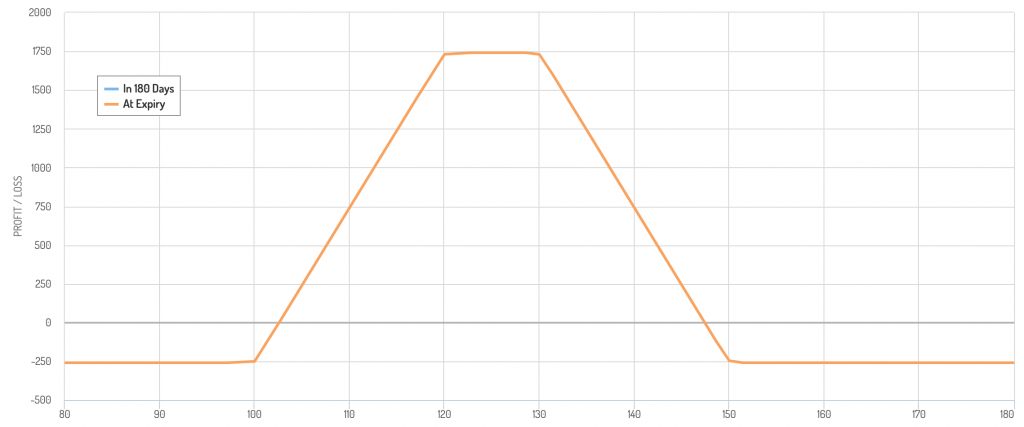

(Source: Interactive Brokers)

Your options payoff diagram looks like this. Again, a bull call spread is effectively a collar trade structure.

Your upside would be capped, but you would have lower downside.

b) Overweight the short side of the trade

If you want to whittle down your options costs further, you can actually overweight the short side of your trade.

That means your upside won’t simply be capped, your profit/loss will actually go back in the other direction (i.e., against you) once the price transcends that point.

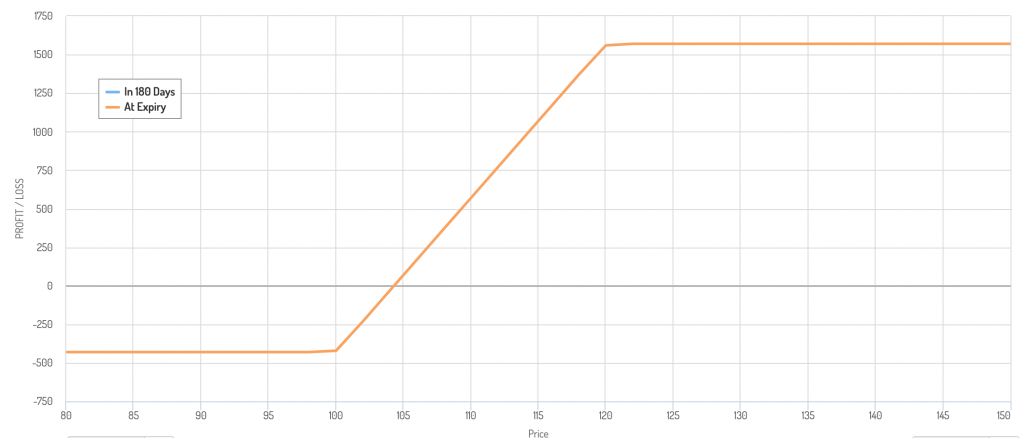

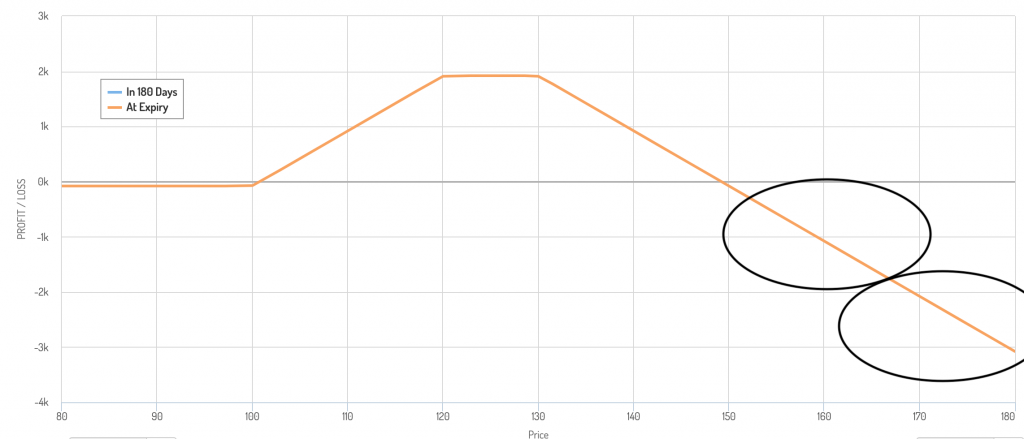

Using the same running example, with a 100 call (long) priced at $900 and 120 call priced at $470, if you sell two of the 120’s you will actually get a credit of +40: -$900 + 2*$470

Your payoff diagram now looks like this:

You may recognize it as the same type of payoff diagram associated with a short straddle trade.

It essentially is a short straddle that’s been shifted to the right. In other words, instead of the traditional short straddle where the “point” is ATM, this version is shifted to a price OTM as a way to express a bullish position on the price of the underlying.

Let’s look at the pros and cons.

Pros

a) Your cost of being long is significantly reduced.

In fact, if your transaction costs are managed well (i.e., tight spreads, good execution), you’ll get a credit in this case while also maintaining the benefit of being long. You no longer have that sharp trade-off of being long via a standard vanilla option – long but expensively so.

In this type of trade structure, you are long, your downside risk is capped, and it’s basically free.

b) You still get the same linear, delta-1 payoff like being long the stock when it enters ITM.

c) You are long the part of the distribution that is most likely to happen ($100 to $120, as obviously price has to run through those numbers first) and short the part of the distribution that is less likely ($120 forward). You are also profitable in the $120 to $140 range even if it does occur.

Cons

a) Most importantly (i.e., matters related to your risk), if the trade goes too well, you start not only losing profitability, but can start losing money outright.

b) The fact that your maximum payout is at $120.

While the idea behind this trade structure is to minimize costs while limiting your downside, the fact that it caps out at a specific price is arbitrary.

This is why some traders prefer strangle type trade structures instead. It means they will have maximum profitability within a fixed range rather than some arbitrary point.

Strangle-shaped payoffs can also make the position easier to manage since the delta will remain the same within a range rather than be constantly adjusting as it is for straddles.

Strangle alternative

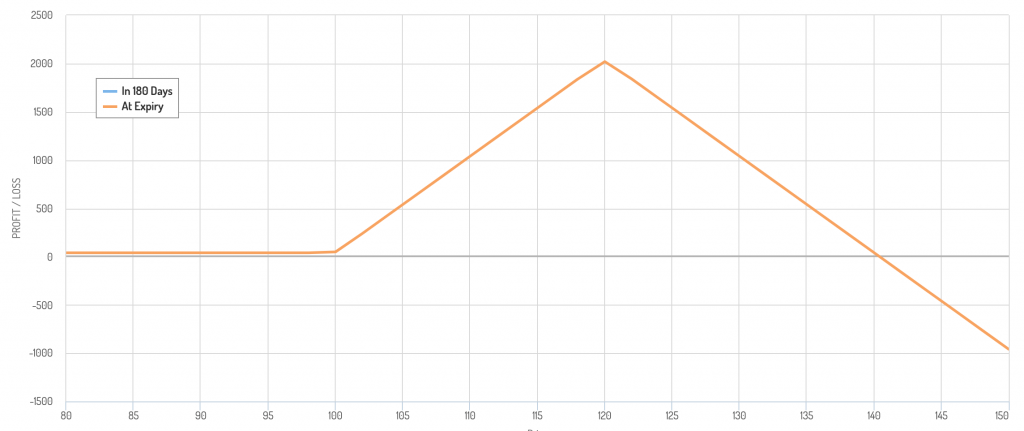

One example of a strangle structure would be the following:

– Security price at $90

– Long 100 call

– Short 120 call

– Short 130 call

– Long 150 call (to cap downside if the trade goes “too well” – i.e., from $90 past $140)

This would effectively look like a short strangle.

Given that the price is at $90 in this example, you’re effectively betting on a moderately bullish outcome. It has fixed downside if the trade does poorly or if the underlying goes up a lot.

In general, to avoid losing money if the trade goes better than expectations, it’s better to buy a cheap call for prudent risk mitigation purposes.

You would make money between $102 and $148 and your maximum upside (between $120 and $130, or 33-45 percent gain) would be 6.7x your downside.

Notably, if you’re wrong, you lose only a little bit. If you the moderately bullish move of some 30-50 percent, instead of making 1.3x-1.5x you instead can make 5x-7x. This is where the inherent leverage of options comes from.

Buying the far OTM call is important to complete the strangle-like trade structure.

That way you don’t have to worry about such tail risks occurring, as illustrated below.

Markets can move more than you expect. So having those open tails can be dangerous.

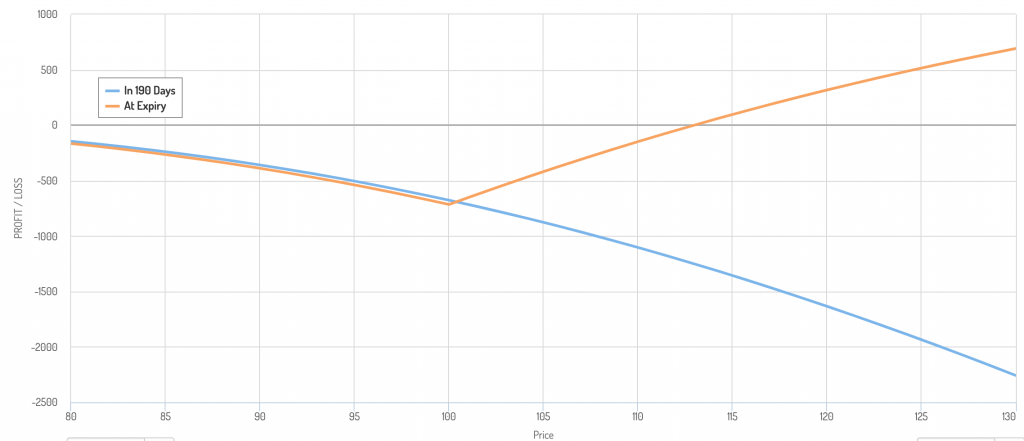

c) Sell an option of a longer maturity

If you want to go even further in reducing options costs, you can sell a longer maturity.

The main benefit to this, naturally, is that the longer maturity has a higher premium. If the position goes against you, you’ll get more of an offset from the falling premium, holding all else equal.

This needs to be handled carefully, however, because you are introducing a maturity mismatch into your portfolio.

The payoff diagram is also not very intuitive like it is when the maturities are the same. This is because you have the two different time elements to think about.

The diagram basically tells you that your lowest P/L point (i.e., most negative loss) – when both options are active – is on expiration day of the long call option when it’s ATM.

Intuitively, this should make sense. When your first call option expires (the one you’re long) and you are ATM, it expires worthless.

Then all you have left is the short call option, which introduces the unlimited downside portion.

This is what the blue line tells you in the graph below. Once the long call peels off, you’re left with the unlimited downside short call. The orange line pertains to the diagram on expiration day before the long call expires worthless (if it does).

When the first option expires, you would then need to re-establish an options structure (i.e., long another call) to mitigate the risk. This, of course, would increase your costs of the total trade structure.

(Getting rid of that downside risk would also likely boost the margin in your account, as your broker will no longer require you to hold capital against it.)

Another way is to simply cover the short calls (i.e., buy them back) to get rid of the liability.

This is especially viable when the price of the underlying security went the other direction. This means the long shorter-duration calls expired worthless and the short long-duration calls also lost the bulk of their value.

If your long call option goes ITM, you can make a nice profit from that. But the issue is that your short call(s) are getting higher in value (bad if you’re short) at the same time.

When your call expires (if you choose to hold it to expiry), then you will need to manage the short calls.

When you do this, it requires careful risk management. This will commonly entail covering the short calls, buying calls, and/or delta hedging (i.e., buying the underlying).

It’s generally not advisable to introduce a maturity mismatch into your portfolio. But it’s an option for more sophisticated traders who know how to handle these risks in a prudent way and to increase their return to risk potential.

Final Thoughts

To build a balanced portfolio with options, first you need to determine what your strategic asset allocation mix will be.

What assets do you want to own and in what quantities?

This is an asset mix that will help you do well in all economic environments no matter if there’s rising or falling growth or rising or falling inflation (the main two big macro forces that move asset classes).

Mixing assets well will help you achieve more return per unit of risk, lower your portfolio volatility, lower your left-tail risk, lower your beta to equities, among other benefits.

Then you need to think about trading structuring. You can do this by buying the underlying assets. You can also buy the underlying assets but apply a volatility risk premium overlay (VRP overlay).

This article covered options and efficient option structuring to help you have upside while also limiting your downside. Options can help you capture the portion of the returns distribution you’re looking for while also helping to improve your return to risk ratio.

To use options in a way that maximizes their convexity and risk mitigation properties, it’s helpful to use both the long and short side of the options markets.

First, you should make sure that the options market you’re trading is liquid. If not, or it’s not deep enough for your needs, your transaction costs will eat into your profit.

To get the options you own more cheaply, you might:

– buy something deeper OTM

– buy a closer maturity

– look for “underpriced” options (that is, when implied volatility is unusually low)

– buy the option as part of a spread where you go short another option (or through additional “legs” of the trade structure)

The latter portion – using long options as part of a spread – means selling options is a prudent way. Ideally, you’d like to both lower your cost and increase your potential return relative to your risk.

Being able to short options can help you lower your costs and generate an efficient trade structure. Accordingly, this might mean you’re able to buy more of the structure to help you earn more.

Shorting options in this manner mean it can be both return-enhancing and risk-reducing.

To help offset some (or even sometimes all) of the costs of your options on the long side, you might:

– short something that gives your long option the breathing room to capture the fat part of the distribution to make quality gains, but be a strike price close enough to help offset cost as well

– overweight the short side of the trade (you can cover any imbalance by buying far OTM options to offset any tail risk)

– short something with a longer maturity

Done well, your options trade structures should have many multiples of upside for each unit of risk you take on.

They should also be cheap enough such that if the trade doesn’t work, you don’t lose much.

There’s a creative element to it.

While there are certain options structures out there that fit within defined names – e.g., straddles, strangle, condors, bull spread – the general focus will need to be capturing the parts of the returns distribution you’d like without paying too much for it.

The best types of trades are the ones where you have the opportunity to get as many multiples of return per unit of risk you take on as possible.

And not simply the notion of getting high returns in a limited-risk way, but having a material chance of capturing it as well.

If you can use options in a thoughtful way, you can make a lot when you’re right and not lose much when you’re wrong.

Beyond ‘delta-one’ pay-off instruments

While many traders use “delta-one” or linear pay-off instruments – i.e., owning the underlying asset – the nuances of how ideas are expressed can be vital for both returns and for risk management purposes.

Once you have your allocation or are concentrated on themes that are inherently symmetric in the first place, options can add another layer of convexity through the ways the trades can be structured, with an additional level added through prudent risk management.

Option structures can be tailored to the market climate.

For example, in a low volatility environment, outright long volatility structures might be more common as there is not as much need to reduce costs. In a high volatility environment, one might be more likely to use more sophisticated structures to cut costs.

More exotic options structures (e.g., spreads) can cut costs materially (by more than half) in exchange for lower upside or potentially earlier expiration.