4 Alternatives to Bonds (and Cash)

With short-term and long-term interest rates at zero in all of the main reserve currencies (USD, EUR, JPY), market participants will have to increasingly look for alternatives to bonds and cash.

Cash and bonds are two of the main three asset classes in addition to stocks. But all developed economies are suffering from high debt loads. That means they need to keep interest rates on it low. This keeps debt servicing payments manageable and prevents their economies from contracting due to the debt burden.

Nominal interest rates have to be kept below nominal growth rates to prevent the debt from growing faster than goods and services output.

The upshot of this for market participants is that cash and bonds no longer make for viable investments. A zero percent or near-zero percent return for cash and for certain types of bonds make them virtually useless for income generation purposes.

Outside that, there are three other adverse implications:

i) a low discount rate on earnings

ii) little risk diversification

iii) a weak currency

Low discount rate on earnings

A low discount rate on earnings pushes up the values on practically all other assets.

The value of a business is the amount of cash it earns discounted back to the present. If the discount rate on a risk-free asset is zero, then you’re simply left with the risk premium.

If a bond yields zero and stocks traditionally earn a risk premium of about three percent extra beyond that, then stocks are discounted at a very low single-digit return.

People can no longer rely on traditional earnings multiples to inform what assets “should be trading at” when short-term and long-term interest rates are zero.

The standard 10x to 20x multiples don’t apply.

The inverse of an P/E ratio or earnings multiple is the earnings yield (i.e., earnings over price).

If a stock is trading at 30x forward earnings, the inverse of that is the projected yield (about three percent).

If a bond gets you nothing, that three percent or so could actually be a reasonable yield.

All the liquidity associated with low rates across the curve is going to bid up the price of everything and make things unattractive to own relative to their risks.

Little risk diversification

Over the past several decades, traders and investors have grown accustomed to having bonds act as a positive yield hedge against a drop in equities.

A drop in income in the economy is traditionally offset when the central bank lowers interest rates to stimulate additional credit creation in the economy. Financial assets bottom, then the economy bottoms, and things turn upward again.

A drop in interest rates is good for bonds, helping offset some or all of the losses on stocks, depending on the allocation.

Now, when rates are zero this has created a very problematic scenario for traditional investment strategies that rely on this offsetting relationship. Such approaches include 60/40 stocks/bonds allocations.

There’s no longer a way, through traditional monetary policy, to arrest a decline in equities.

A zero percent cash yield and a zero bond yield means you can’t really lower the discount rate, so the downside is bigger on equities if those earnings fall.

When stocks fall, the bond rally often diversifies away that risk. But now, about 80 percent of all local currency government debt, weighted by market cap, has a yield below one percent.

So the equity side doesn’t have much downside protection and the bond side has no yield. And there are asymmetric risks because yields can only go so low.

As a result, the only way you have to put a floor under the economy is through monetization and fiscal policy. That’s a political process.

And whenever you have the mix of circumstances that we do now, you get more social and political tension. That threatens harmony and the ability to do the things that are in the best interests of the whole when each side is so hung up in the fight.

A weak currency

Even with monetization and fiscal policy, creating a lot of money to relieve the debt burden is not free.

The pressure can come in one of two ways: the currency side or through higher interest rates.

Central banks don’t want interest rates to rise. Anchoring them low keeps economies and markets going.

So, it’ll have to go through the currency side. Countries that don’t have reserve currencies, or don’t have an independent monetary policy, don’t have the luxury of being able to print money to the extent of countries that have both a reserve currency and the ability to create money (like the United States).

Emerging markets have to engage in more austerity measures and take the effects through their incomes. Most developing economies still have interest rate policy available to them being off the zero interest rate floor. That’s a plus. But, at the same time, others don’t.

The implication for the US is a weaker dollar over time. A weaker currency relieves debtors with fixed-rate obligations.

It’s also stimulative to financial assets by making them go up in money terms. It also helps exporters by making their goods cheaper in foreign currency terms.

Bonds and price risk

Even for certain types of bonds that provide 0 to 1 percent yields, their duration gives them price risk. So that annual yield and then some can be wiped out with a small price move for those trading these instruments.

Before, when bond yields were two percent, for example, at least one could say it might match inflation and spending power might not erode. In addition, if equities take a spill, then you still probably have somewhat of an offset if caused by a deflationary drop in credit creation (the way it normally works).

A two percent return, with that two percent continually invested, would mean that you’d get your money back in 35 years in coupon payments assuming you could continually re-invest at that two percent.

At zero or thereabouts, there is practically no income generation argument.

Long duration bonds could be a means to speculate on interest rates falling further. They could still be something of a capital preservation instrument. Or if someone believes that inflation will fall or deflation will set in, then these instruments could provide higher returns in real terms. We covered some of these arguments in more depth here.

So, it’s fairly obvious that with interest rates at or near zero (sometimes below zero, depending on where you go) and being anchored down there by central banks, bonds provide neither returns nor reduce risk.

Nominal rate bonds (which are almost all government bonds) can go a little bit below zero. For example, US Treasuries could go down to maybe minus-1 percent. That would put it on par with the lowest rates in the world.

But there’s no limit to how interest rates can go. So while there’s limited upside, there’s unlimited downside.

Even a moderate bear case – e.g., real interest rates normalizing and inflation going up to (say) four percent – would produce something like 3x more losses than US rates going down to the lowest in the world.

The asymmetry to owning nominal rate bonds is out of whack.

A New Paradigm

For those who rely on returns from bank deposits and bonds, they’ll have to adapt or have lower income.

The same is also true for stocks. Returns on developed market equities, over a long enough period, might be passable in nominal terms. But they’re unlikely to be good in real terms.

Many people are still piling into them because investment decisions are done on a relative basis.

What are the risks and rewards of A relative to the risks and rewards of B?

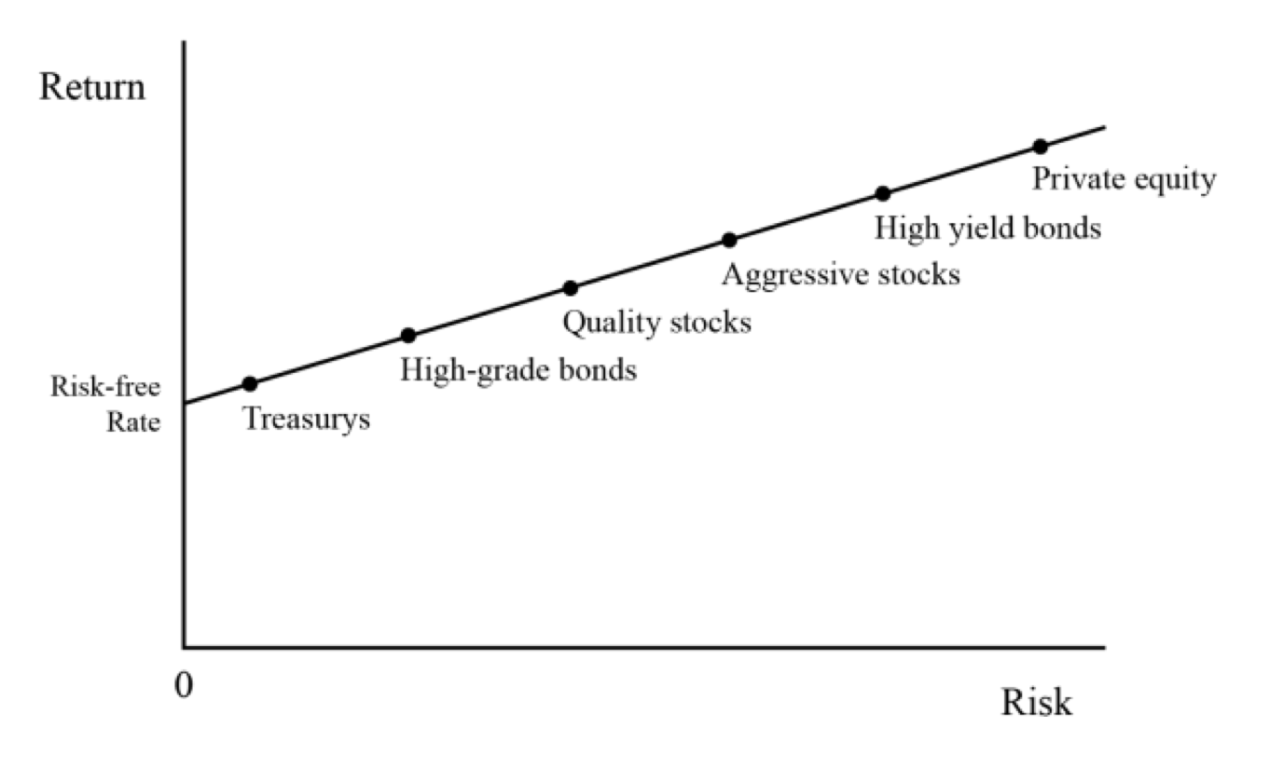

If we plot the relationship between risk and return, we see a curve going from the lower left to upper right to show that more risk entails more demanded return. One of the natural equilibriums between the markets and economies is that riskier forms of capital should exhibit higher returns relative to less risky assets.

Risk vs. Return: Asset Classes

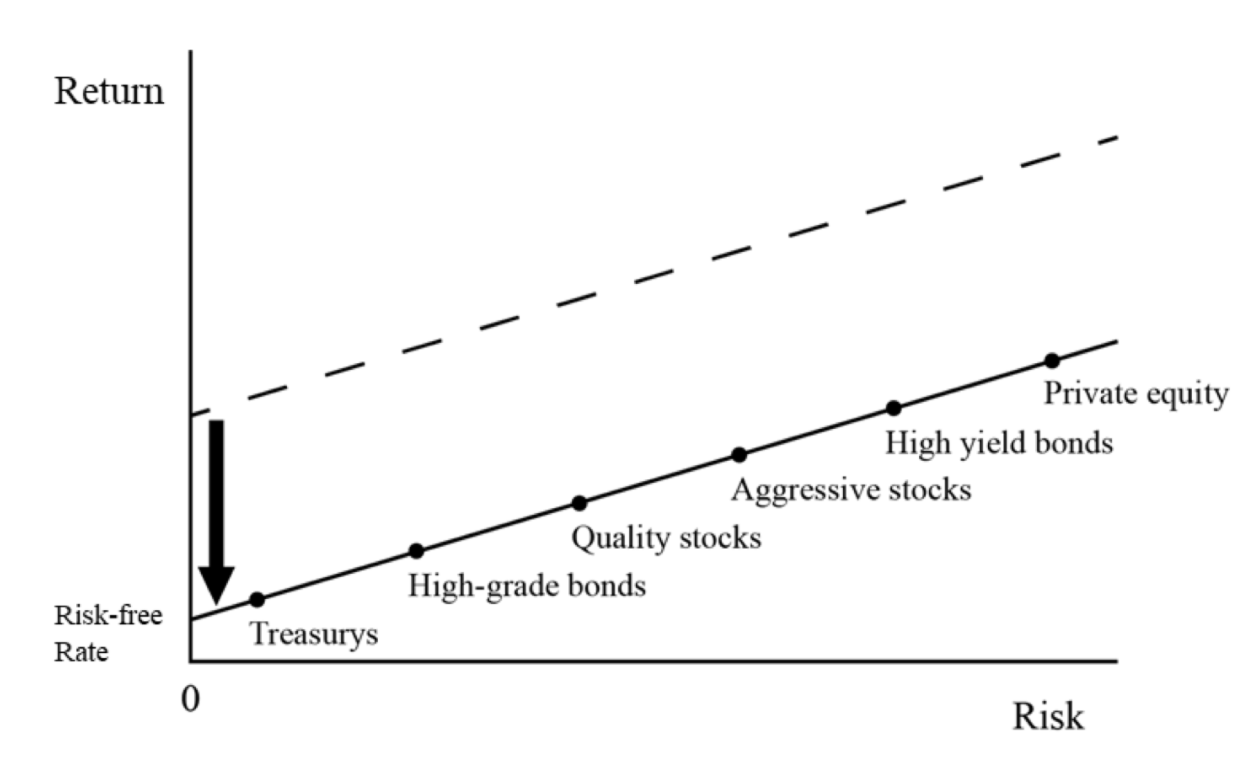

When you lower the interest rate on cash, holding all else equal, that increases the price and lowers the returns of other asset classes as well.

The entire capital market line falls.

Falling short-term interest rates reduce the yields of other asset classes

In 1981, a 10-year bond yielded 15 percent per year and fallen to close to zero since.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

So over the past 40 years, basically any combination of holdings in cash, bonds, and stocks has worked out well.

Even something basic like a third in each category has made around percent per year.

Portfolio Allocations

| Asset Class | Allocation |

|---|---|

| US Stock Market | 34.00% |

| 10-year Treasury | 33.00% |

| Cash | 33.00% |

Here are its returns from 1972 forward.

Portfolio Returns

| Portfolio | Initial Balance | Final Balance | CAGR | Stdev | Best Year | Worst Year | Max. Drawdown | Sharpe Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portfolio 1 | $10,000 | $420,922 | 7.95% | 6.01% | 23.81% | -5.44% | -13.15% | 0.54 |

Now if you did a third in each it wouldn’t even get you 2 percent a year. Spending power would actually go down because it’d be lower than expected inflation and you’d have to pay taxes on any income you took out of it.

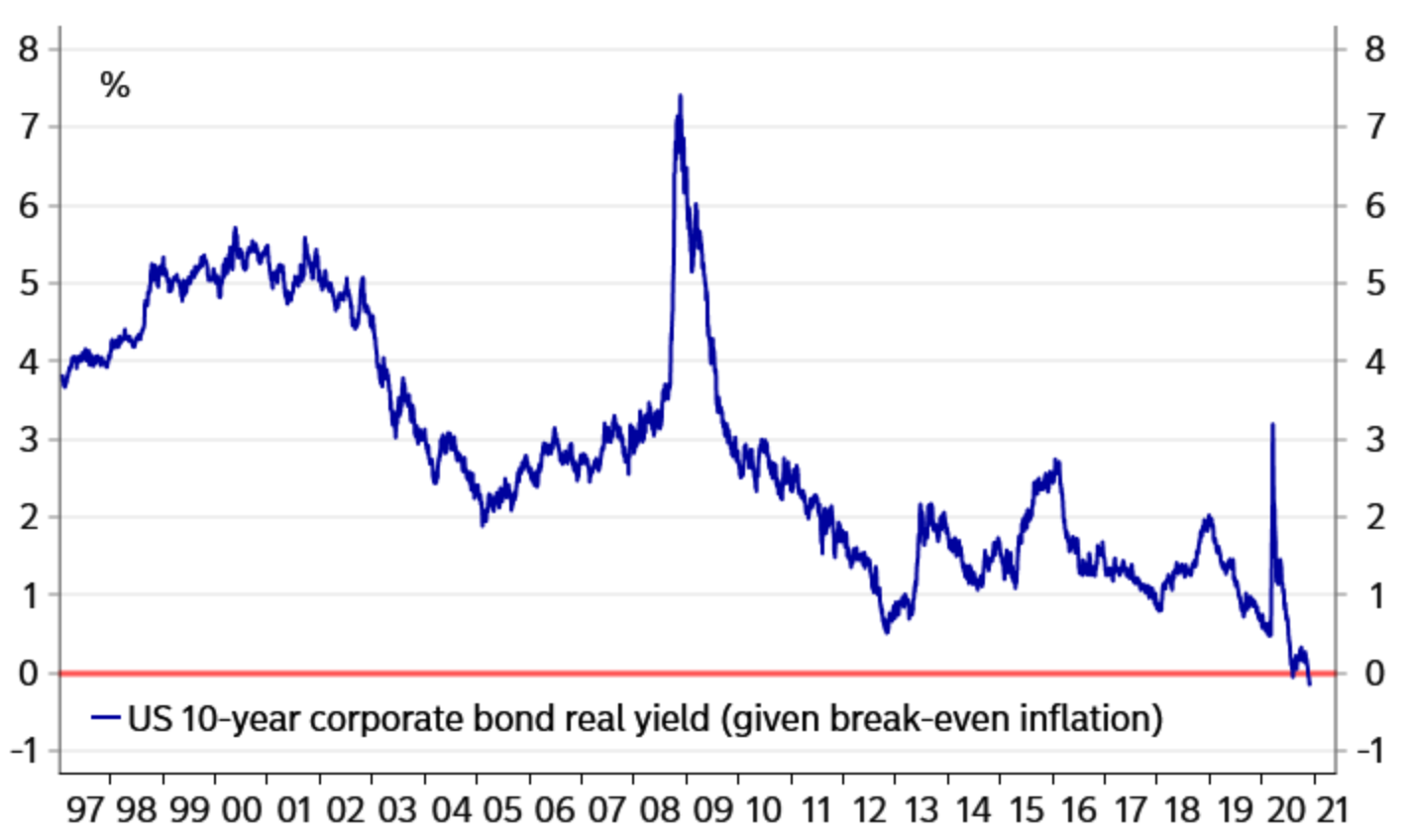

Moreover, we’re an environment where real yields on corporate debt are below zero.

Corporate real yields

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Back in the early 1980s, with a risk-free rate of 15 percent per year locked in over the next ten years, that meant in order to attract capital to quality corporate bonds, the yield had to be somewhere above that.

Corporations were borrowing at 16 percent or higher. So were consumers, with mortgage rates in that vicinity as well.

The get capital into high yield bonds, returns had to be somewhere around 18-20 percent depending on the credit risk.

But even high yield bonds were not well accepted yet as an asset class by that point. So, even 18-20 percent yields on those assets often didn’t get a lot of traction.

On top of that, investors didn’t need to take that kind of risk back then to reach their nominal return goals.

Now, when the rate on cash is zero (or below zero in some countries) and the yields far out are also zero, negative, or very low, then even 5 percent returns on some assets are highly appealing.

Bonds have become like cash in the sense that they are closer to a funding vehicle than an investment vehicle.

More investment managers are going to buy traditional investment assets on leverage – borrowing at close to free rates – in order to hit their return goals.

Putting money into high yield credit at 5 percent returns would have seemed strange back in the early 1980s.

However, because now the rates of return on cash and bonds are so low, the prospective return needed to attract capital in other riskier asset classes is not particularly high. This accordingly bids up their prices.

Cash and bonds are no longer very good investments

Cash and nominal rate bonds are bad investments because governments are “printing” and issuing a lot of it and it doesn’t yield anything.

Cash might seem safe because its value doesn’t move around much. But it’s the worst thing you can have over time. It gets perpetually taxed through inflation by a little bit per year, and it adds up over time.

Nominal rates on it are zero (or even negative depending on where you go), so real returns are negative. In other words, its purchasing power chronically declines.

Where to Go: The Main Alternatives to Bonds

There are really four main alternatives to bonds and cash.

i) inflation-linked bonds

ii) gold, precious metals, and other commodities

iii) diversifying the countries you have exposure to, and

iv) finding more stocks and companies with stable cash flow

We’ll go through each individually.

Inflation-linked bonds

Moving part of the allocation away from nominal rate bonds and into inflation-linked bonds is one option.

As mentioned earlier in the article, nominal interest rates can only go so low – around zero or a little bit below.

So, the price upside on a bond yielding 0 to 1 percent is negligible.

But real interest rates can go very negative if inflation were to go up. That means the prices on inflation-linked bonds don’t have the same type of ceiling.

Gold, precious metals, commodities

Moving into something like gold can make sense, which functions like the inverse of money.

The value of gold just reflects the value of the money used to buy it. Gold’s utility is not increasing when its price goes up. The supply of money has gone up, making gold’s value higher in money terms, and money’s value down in gold terms.

This is helpful to have in a portfolio in a time like today when central banks are creating a lot of money to service debt.

Debt is a “short money” position. In other words, it eventually needs to be covered with money.

When a country has too much debt and owes too much money, and it has an independent monetary policy that allows it to print money, it will create money when it needs to avoid the debt from becoming a problem.

Financial market signals often pickup when this is becoming an issue, as they discount what’s likely to transpire.

The 20 percent drop in markets in Q4 2018 was an example. The US markets also peaked in October 2007, somewhere about a year before the blowup in September 2008, which lingered for another six months before the market bottom.

The biggest part of the debt equation at the sovereign level is whether the debt is denominated in a country’s own currency.

When it’s denominated in their own currency, they can handle it in the usual ways:

i) Change the interest rate on it

ii) Write some or all of it down (30 to 40 percent write-down is typical in major debt crises)

iii) Change the maturities on the debt

Even though the main developed economies (US, developed Europe, Japan) and China have debt loads that are too high relative to income, the debt is heavily denominated in their own currency. They can control the situation as a result.

If they write some of it down, change the interest rate on it, and spread it out such that they only have to pay (for example) a couple percent per year, then it becomes much more manageable.

All that will nonetheless involve a lot of new money being created. That has implications for the soundness of money.

Countries cannot create money, issue debt, and have perpetually large deficits without impacting the soundness of their currency.

This is what drives gold. When people see a lot of debt being issued and with low yields and money being printed to devalue cash, they naturally want currency hedges.

Historically this has commonly meant gold.

Silver serves a similar purpose, but has industrial uses and is an even smaller, less liquid market.

Gold is a better diversifier and can make sense in most portfolios. Some ~10 percent can be a reasonable allocation.

Geographic diversification

There are other countries that have positive nominal bond yields, so those are an option to make money on nominal rate bonds if the global disinflationary trend continues.

In general, investors are overly concentrated in their domestic currencies and markets. Currency and geographic diversification is undervalued.

Capital is always shifting around. It’s not just shifting around domestic asset classes. It’s moving into other geographies and currencies as well.

As capital shifts more from West to East – because emerging Asia is growing faster and becoming a rising influence in the world – this will become more important.

This is not just China, but there are a number of other countries in the East where the environment is different.

They didn’t have to balloon their deficits in response to the virus, as the US and other Western countries did by trying to keep people home and send income replacement support to those who needed it.

This caused incomes and spending to go down while liquidity expanded broadly. This lowered economic production yet pushed financial assets higher to multiples on earnings that are extremely high historically.

In many Eastern countries, they still have a normal interest rate (i.e., cash rate), a normal bond yield and normal yield curve, and stocks are reasonably priced.

So, there’s a material divergence across parts of the world.

As an investor or trader, ideally you don’t become so centered on your domestic markets where you only make bets on the opportunity set in your home market.

If you’re from the US or developed Europe, there are intractable issues holding back quality returns that ideally you don’t want to be exclusively locked into. When things are going up everything seems fine even though it’s generally an indication that things are becoming more expensive.

US-centric portfolios have naturally done exceptionally well as a whole over the past several decades. But the returns of the past, especially in real terms, will be nothing like the returns of the future.

Geographic diversification is a crucial element.

The US’s shrinking reserve status

While the world is accustomed to the USD as the world’s top reserve currency, the US’s financial situation is putting this at risk (eventually).

The US is now just 20 percent of the global economy yet 60 percent of global payments and international debt. That eventually has to come closer together.

The US isn’t going to raise its growth rate to take more from the world on a relative basis. It’s the currency that will have to come down over time.

It’s not going to happen quickly. Loss of reserve status always comes with a lag after an empire’s relative standing fades. A new system has to be deemed better first. But more capital will shift out of the US dollar over time.

Certain stocks and business

Certain stocks that involve selling products people need to physically live (e.g., food, basic medicine) can be good stores of wealth.

These companies don’t rely on interest rate cuts to help offset a loss in income and will fairly reliably grow their earnings over time.

They can function like a type of bond alternative.

They won’t have the big ups and down like companies that are highly tied to how the economy does, like a manufacturing business.

Something like a movie theater business is not a good store of wealth because people don’t have to go to the movies. The same thing with malls. People don’t really have to go to the mall with so much commerce now done online.

Certain technology companies are in this “store of wealth” boat as well.

Companies involved in creating the technology that’ll drive the big productivity gains going forward (e.g., 5G, quantum computing, AI chips, data and information management) can serve the same type of purpose in a portfolio.

Differentiation between countries and sectors

Even though the US and UK stock markets were some 90 percent correlated in 2020, the difference in actual returns was around 30 percent.

If you look at the correlation between sectors, you saw some 80 percent covariance. Yet if you look at the divergences in outcomes by sector, tech outperformed energy by some 70 percent. Tech and banks also saw a huge difference.

More tech companies are viewed as fitting the “store of wealth” concept and long-duration assets that can do well in a reflationary environment.

Other industries like energy are being hit by lower commodity prices (e.g., less demand for travel and less energy usage). Banks are seeing their net investment income crimped due to a lower spread between short-term borrowing rates and long-term lending rates.

Tech companies have different economics where they have lighter balance sheets, and are responsible for creating certain products and services that help drive higher productivity outcomes in some way.

Even though the liquidity being produced by governments did its part in buoying virtually everything to some extent, it was a very nuanced environment. The averages were not really representative of anything.

And a lot of these differences aren’t going away. Clearly, the virus changed spending patterns and made a big difference on certain types of businesses. The response to those spending patterns was a lot of government liquidity targeted to the businesses it wanted to save.

The adverse economic impact is hitting some sectors and some countries hard and the liquidity in response is benefiting some assets and not others.

You have the stores of wealth (some stocks, gold, some commodities) that benefit from the liquidity effect and you have some types of assets that are hurt by the contraction in incomes.

Until the virus impacts totally go away, that will be a persistent pressure.

Doesn’t holding a balanced portfolio involve holding a lot of bonds?

In other articles, we went through how to construct a balanced portfolio. Namely, what’s a mix of assets that can do well in any market environment?

Nominal rate bonds have traditionally been a material part of this allocation.

With the circumstances we’ve mentioned in this article, nominal rate bonds are no longer as big a part of that.

A balanced approach to constructing a portfolio is not about a particular asset allocation, nor has it ever been dependent on any particular asset class.

Protection is more likely going to come from other assets and asset classes, like gold, inflation-linked bonds, assets in different geographies and currencies, and certain types of stocks and private assets.

Nominal rate bonds will still remain a piece of the balanced portfolio approach.

When they have positive yields in countries and currencies you might want to have some exposure to, they can make sense to have. Many Eastern countries have a normal short-term interest rate, positive bonds yields, and a regular yield curve.

Investors tend to get locked into an approach that strongly biases them to their domestic markets. They stick to what they know of and have access to. For a US-based investor, that usually means all stocks (usually all held long), all US companies, and all dollars.

Even if you own a bunch of stocks, that’s a very concentrated portfolios that’s going to have a lot of big ups and down.

It’s heavily biased toward a particular type of environment that won’t be able to take advantage of the fact that capital and wealth mostly shifts around rather than being destroyed.

As part of a balanced allocation, nominal rate bonds will be less of a part of it provided where the yields on them are in all the main reserve currencies. They’ll still be there, just less of a piece of it.

The main danger of a shift out of nominal rate bonds

When investors don’t want nominal rate bonds, their first choice is usually equities.

That creates two problems. The second one is related to the first:

i) It leads to further overvaluation in equities, bidding down their forward returns.

ii) Equities may not actually benefit from this environment if inflation is produced.

With respect to the first issue, when the time comes, this can lead to exacerbated shifts in the other direction, especially as equities are purchased on leverage. When there’s no alternative, people will crowd into stocks.

But only getting a few percent out of them per year (i.e., the effective forward return when bid up to nosebleed levels) means they’ll provide very little in real purchasing power. Yet it involves taking on a lot of risk.

The second relates to the fact that investors and other market participants generally extrapolate what they’ve gotten used to.

Over the past several decades, bonds have provided an offset to losses in stocks because inflation has generally steadily fallen over time.

But that’s not always going to be the case.

If you see inflation, that raises equilibrium interest rates and the discount rate at which the present value of cash flows is calculated rises, decreasing their prices.

When financial assets are discounted at very low rates, that lengthens their duration. In turn, that makes them more sensitive to movements in interest rates.

In terms of a prudent asset allocation, it would be wise for investors to go beyond just stocks and bonds from their own markets and in their own currency.

Markets in the US (and throughout the developed world) discount very low inflation going forward over the next 10 years (1.89 percent) and 30 years (1.88 percent).

Breakeven inflation rates

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

If those rates climb higher, this will hurt not only nominal rate bonds – which is the largest broad asset class globally – but also hurt equities as well with no corresponding increase in real growth to help offset a corresponding shift higher in interest rates.

Conclusion

If cash and bonds are bad there are generally four main alternatives:

i) different types of bonds

ii) gold, precious metals, and other commodities

iii) different geographies and currencies

iv) certain types of stocks and businesses

Going forward, with the returns of nominal rate bonds virtually non-existent in ~80 percent of the world’s supply of sovereign debt, more market participants are likely to shift out of them.

Investors, reserve managers, and others will look at the situation where holding money in nominal rate bonds doesn’t provide any return and they don’t reduce risk in the way that they used to.

Moreover, governments are having to try to rectify their debt imbalances by creating money, which devalues it.

More and more, it will boil down to what’s a good store of wealth.

Safe used to mean dollars and Treasury bonds. That’s not really the case anymore. People will want more alternatives to bonds.

It’s not likely to be a big shift out of nominal rate bonds right away, but rather one that will occur over time in terms of demand for many other types of assets (e.g., precious metals, inflation-linked bonds), capital flows into other countries and away from the main reserve currencies, and continued demand for certain types of stocks.