Next Generation EU Bonds: The New EU Reserve Asset?

A new supranational issuer is set to enter the European financial markets after the EU summit agreed to a €750 billion recovery fund, known as Next Generation EU (NGEU).

Because of pre-existing issues related to stagnating productivity, aging populations, and high sovereign and corporate debt, EU borrowing will continue to increase in excess of output.

On the surface, one would assume that increases in borrowing are negative for the currency where it’s being done.

Holding everything constant, it is, as it’s a claim on future income. Issuing debt to meet obligations is commonplace throughout the developed world and will only accelerate with high debt and very high levels of unfunded obligations (related to pensions, healthcare, and other liabilities).

However, if there’s the demand for the credit and the demand for it is in excess of the supply, that’s positive for the currency.

The EU’s scarce reserve asset(s) problem

Since the institution of the euro currency in 1999, the European Union has struggled to establish a reserve asset that will compete against US Treasuries in status and size.

German bunds are the most in-demand form of credit in the European Union as Germany is the region’s largest (and traditionally, the healthiest) economy.

But because of Germany’s relative level of fiscal austerity, bund issuance has been low and its availability scarce.

That limits how much savings there is in the euro globally. Accordingly, you can argue that it’s limited the extent to which the euro has come up to challenge the US’s monopolization of currency reserve status.

While the US accounts for only about 20 percent of global activity now, some 60 percent of global savings, trade, and debt is in the US dollar.

That would suggest, going forward, fewer would want to save in the dollar. It’s popularity as a reserve is out of line with its level of economic activity, running on its reputation rather than its true level of financial health.

Some entities holding a lot of that debt abroad (e.g., China) also have material conflict with the US and probably don’t want to be holding a lot of it as time goes on.

The US can unilaterally cut off payments to certain countries, the debt itself doesn’t yield much, and the US’s need to print a lot of it as time goes on to monetize debt and other funding obligations will put pressure on its value.

The EU economy is about 62 percent of the size of the US economy. But in terms of currency reserve status, it lags well behind at only about 20 percent of global savings, trade, and debt. That is a bit higher than its role in global economic output (around 15 percent), but its currency reserve status is only about one-third that of the US.

Reserve status is important because it helps countries borrow more cheaply. Therefore, they can get a higher return on what they spend (or less of a loss) and derive an income effect from it.

Moreover, if and when an economic crisis hits (e.g., 2008, 2020), countries with reserve status can create money to offset the debt and financial burdens without running into issues with their balance of payments (and subsequent currency and inflation issues).

That means less of the impact has to play out in the form of lower incomes, and it’s a great privilege for any country to have and all nations want. That was part of the idea behind the euro in the first place, sacrificing some level of sovereignty for the benefits of a common currency.

Where Next Generation EU bonds come in

The EU itself is likely set to become, at some point in the future, the primary EU-level bond issuer. This will offer investors another type of safe euro asset.

This is positive for the euro currency, which has hit a multi-year high against the US dollar. (The dollar has been weakening due to the subsiding of the crisis-induced squeeze and the US is creating trillions more of the currency to help offset income losses from 2020-related issues.)

(Source: Trading View)

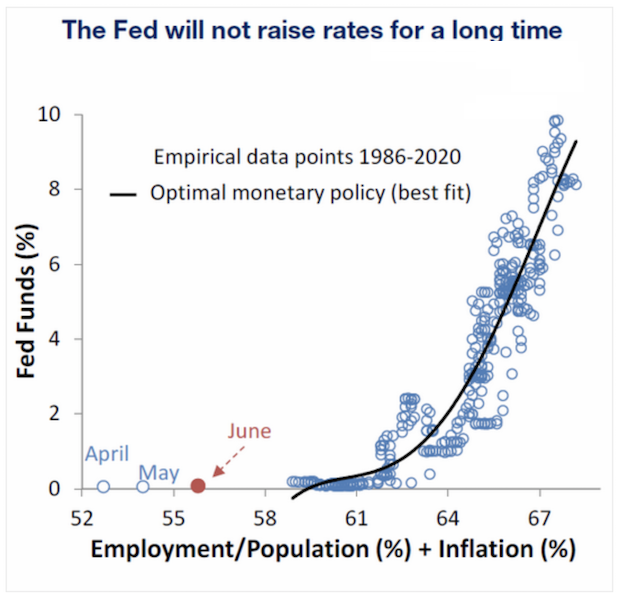

The US Federal Reserve will keep interest rates pinned to zero for a very long time, which will alter how entities invest no longer having an interest rate tailwind. This zero-rate reality holds not just with respect to policymakers’ attitude toward cash, but with respect to longer-duration bond maturities as well, given the debt burden.

The “misery index” – or the sum of inflation and unemployment – is one proxy that some will look at to determine where central bank policy should be. The Fed is very far off from the notion of raising rates.

This is also impacting the dollar’s value relative to gold, which has a long-run value proportional to currency and reserves in circulation relative to the global gold supply. Central banks are printing a lot of money while the global gold stock only traditionally goes up by 1 to 3 percent per year.

The new EU financing of a €750 billion recovery fund and €100 billion SURE program will give the European Union itself a large foothold in the European bond markets, with less reliance placed on any given member country.

These new EU bonds will not be bearish for the currency because of pent-up demand for safe euro assets. They’ll also help with European sovereign bond market liquidity.

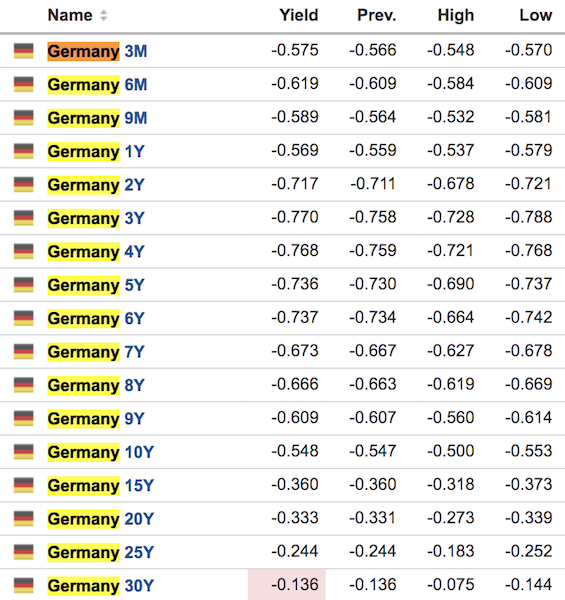

German bund yields are not particularly attractive, expressed below in percentage point terms. They can only be pushed so negative before people go looking for other places to store their wealth.

(Source: investing.com)

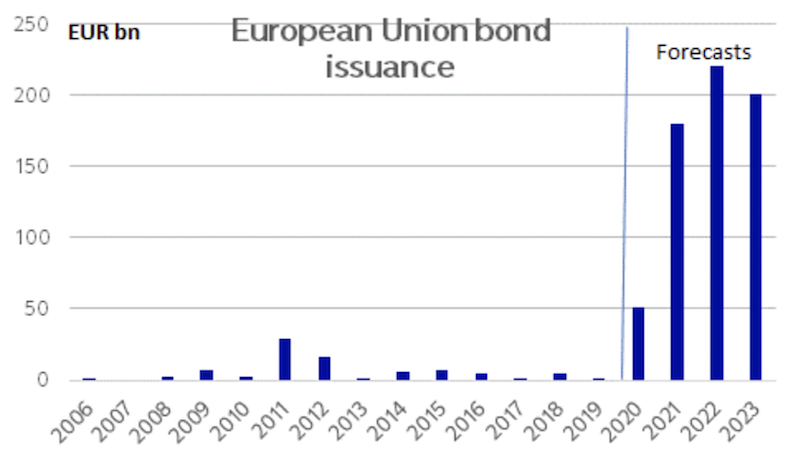

The EU’s highest issuance volumes of the new debt likely won’t occur until 2022.

(Source: Nordea, Bloomberg)

Most of the issuance is longer-duration in nature – typically 3 to 30 years.

This makes sense to lock in cheap funding rates for a long time.

We also see this with respect to US corporations extending their maturities.

Yield to worst is at an all-time low.

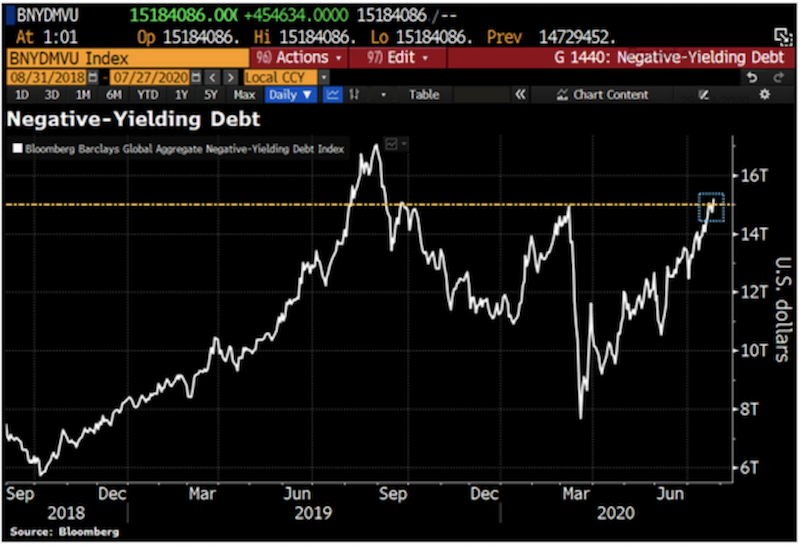

Negative yielding debt is also trending higher, as interest rates decrease and debt issuance increases.

Naturally, you’re seeing a lot of this spill over into higher prices for alternative wealth store holds, like gold and silver.

New Next Generation EU bonds will provide a new supply of assets that will be in strong demand (even though they likely won’t yield anything in nominal terms, or be slightly negative).

They will not yet take the place of German bunds as the top EU reserve asset. But they will still be larger than the current euro area supranational issuers, the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), European Stability Mechanism (the ESM), and the European Investment Bank (EIB).

Net new borrowing will occur until at least the end of 2026. Borrowed funds can be used on loans of up to €360 billion and expenditure grants of up to €390 billion.

The €360 billion set aside for loans may not be used entirely. Countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands can finance themselves more cheaply or at least comparably. So, they may not need to use EU loans. Loan amounts for each member state may not exceed 6.8 percent of gross national income (GNI).

Repayment is set to begin after 2027 and go until 2058, with the amount due each year steady at just under €30 billion. So while the aggregate amount borrowed is high, the annual servicing is quite low.

The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RFF) will make up about 90 percent of the program (€672.5 billion of €750 billion total). Seventy percent of the grants provided via the RFF are committed to 2021 and 2022 expenditures. Thirty percent are expected to be used by the end of 2023.

Will the Next Generation EU program become permanent?

Everything typically costs more and takes more time than expected. This is because nobody plans for the inevitable things that will go wrong. This will be true as the EU recovers from the virus-related meltdown in economic activity.

The hoped for V-shaped recovery will be true for only a slice of the economy (e.g., some tech and digital companies). But it will be more drawn out and unsteady for other sectors, such as travel, hospitality, and leisure. Stores of wealth will do well, while highly economically sensitive sectors will languish for a while.

Though EU bonds are heavily a virus-related issuance, the reality is this program is likely to transform into a more lasting mandate rather than be temporary.

This is likely to make EU bonds the dominant EU-level issuer over the long-term. While EU bonds are a bit cheaper than other forms of high-quality sovereign debt, if the program becomes more permanent and effectively turns the EU into the primary issuer, they will likely trade at a premium relative to other EU debt.

Nonetheless, it will probably take many years to establish this status.

The ECB will be buying some of these bonds to help keep yields in check. When a lot of debt is issued, if demand doesn’t keep up that means the central bank has to step in.

The ECB has a higher issuer limit of 50 percent for supranational issuers (which includes the EU) compared to individual national sovereigns. Simply put, this means the ECB can buy more.

It provides another channel for European quantitative easing (QE). Because of the relatively shallow EU sovereign bond markets relative to the level of QE the ECB wanted to do to support the economy, it has tapped into corporate bonds markets as needed.

The matter of green bonds

European policymakers integrate climate initiatives into their work.

Total climate expenditures from the NGEU and EU budget have been set at 30 percent. That means significant “green bond” issuance is possible from the EU.

Thirty percent of the NGEU, or €225 billion, would represent more than 70 percent of the existing euro-based green bond market.

As a result, the EUR green bond market is likely to receive a boost, even if total green bond issuance doesn’t total that €225 billion amount.

Conclusion

Through the NGEU, the EU at the supranational level is likely to become the largest issuer of EUR-based debt.

One reason why the euro isn’t more of a reserve currency is that there isn’t more supply of the euro area’s primary reserve asset: the German bund. Eighty percent of all bunds before 2020 were already held by ECB and non-residents (e.g., foreign central banks) and that supply was shrinking.

Accordingly, this places less pressure on Germany from other vested interests in the region (other sovereigns, supranational agencies and interests) to spend more so that it can run a small deficit.

By running a deficit, it would have to issue more bunds. Many believe Germany should aim to keep the supply of bunds constant relative to its GDP so long as they hold responsibility for issuing the euro bloc’s de facto reserve asset.

Running more through the NGEU program, and making it more permanent than temporary over time, will reduce some of the onus on Germany.

The EU is planning on new sources of revenue being added to the budget from 2021 to 2027 to complement current sources.

This includes new VAT contributions and custom duties. It’s also likely to include environmental levers such as carbon emissions-based trading revenues (with a ~€10 billion annual target), carbon border adjustment mechanism (~€5 billion annual target), and a digital tax on larger companies (€1-1.5 billion yearly target).

However, these revenue targets are uncertain and perhaps optimistic.

Governments need to collect more revenue, but they also need to do it in a way that doesn’t adversely impact incentives and encourage tax migration of assets and people.