Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) | What It Means for Markets

Developed market countries have very messy financial situations. Because interest rates are already at rock-bottom levels and quantitative easing (asset buying) programs have mostly run their course, pushing money and credit into the system to relieve debt burdens requires tertiary forms of monetary policy. Accordingly, this is leading to concepts of how to pay for everything via ‘Modern Monetary Theory’, also known as MMT.

Modern monetary theory is simply a new name for various forms of fiscal and monetary policy coordination, as has been required during deep economic downturns. Many of these policy forms have, in actuality, been deployed in a variety of ways over thousands of years of economic history.

Accordingly, there is nothing really “modern” about so-called Modern Monetary Theory.

MMT, in the way most people think of it as, is a new name that references a very old idea – the government monetizing debt or participating directly in spending and investment programs.

It’s the notion that government spending is not revenue- or fiscally-constrained but only inflation-constrained.

Put another way, it’s the notion that if the government owes money, it can simply create the money to relieve the burden until the point where price inflation becomes too onerous or the depreciation rate in the currency becomes unacceptable.

US financial situation

In the US alone, halfway through 2020, there’s the following financial reality:

– $26 trillion national public debt

– $52 trillion private sector debt

– $21 trillion Social Security liability

– $32 trillion Medicare liability

– $148 trillion unfunded liabilities

– Total: $279 trillion

Broadly there are three ways that government can make their finances viable:

i) Increase tax take

ii) Cut spending (that doesn’t produce more in return)

iii) Depreciate the currency to relieve debt burdens

We’ll go through each individually and cover why the third is usually the inevitable route governments take.

Taxes/Revenue

Annual US GDP is around $20 trillion. Federal tax take is just over $3 trillion per year. At the state level, it’s around $2 trillion annually.

While the government needs more revenue, it’s not as simple as raising existing take rates or creating/expanding new forms of taxation.

Hiking tax rates can be hard to do in many circumstances because it produces arbitrage effects. For example, if tax rates go up in one jurisdiction, holding all else equal, that incentivizes capital and people flows to lower-tax jurisdictions.

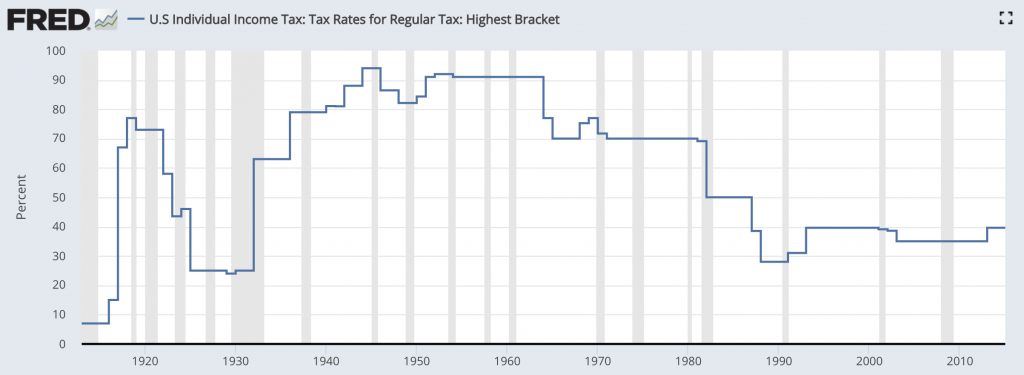

In the US, the highest individual tax rates were north of 70 percent before 1981 and over 50 percent before the 1986 reform. Few paid these high rates “as advertised”. Individuals became corporations or had income reclassified (e.g., long-term capital gains) instead because such rates were materially lower.

(Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury. Internal Revenue Service)

You can see throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and into the 1960s, the top tax rates were over 80 percent and often over 90 percent.

When CBS paid Jack Benny more than $2 million to bring his radio show to the network in 1948, it was treated as a long-term capital gain instead of individual income. That saved him around $800,000. The long-term capital gains rate then was about 25 percent.

When General (and later US President) Dwight Eisenhower earned $635,000 from his memoir “Crusade in Europe” the income was treated as a long-term capital gain and saved him about $400,000.

In 1952, when the top tax rate was 92 percent, the top 1 percent of earners had an effective rate of a more modest 32 percent. That’s a 60 percent delta and it was always common in the “high tax rate” era.

In 1980, when the top rate was 70 percent, the effective rate of the top 1 percent of earners was 23 percent. (The rest of the world was more competitive in 1980 than 1952, so the nine percentage-point drop in the effective rate wasn’t merely a function of US policy.)

Since, the effective individual tax rate has averaged to 19 to 25 percent, with the top individual taxable rate of 30 to 40 percent.

There’s a limitation to how much in tax revenue, as a percentage of the overall pie, can be collected. Raising taxes is hard to do past a point because it takes money away from individuals and companies (who may, in turn, spend less on capital spending, labor, and so on) or will shift it to more competitive locations.

The world is more global and human and financial capital is more mobile. This has pushed corporate taxes lower throughout the developed world, as policymakers push to make their economies more amenable to do business (which can help bring in jobs, more output, and more tax revenue). It’s simply a new natural equilibrium. The primary goal is to make the pie bigger and balance dividing it well in light of that.

There’s been some proposals floating around regarding a wealth tax, but it not the most efficient way for governments to collect revenue. Since most wealth is illiquid, taxes most efficiently concentrate around sources of liquidity, such as income and consumption.

Even if a wealth tax is framed as a “billionaire’s tax” it wouldn’t collect much. Even taxing one percent of the $9 trillion in wealth by those with a net worth of $1 billion or higher would hypothetically only net about $90 billion in revenue per year (assuming it was frictionless and the government bureaucracy to coordinate the plan, ensure compliance, and so forth was costless).

That would finance the US federal government’s expenditures for six days per year. Taxes always inevitably run downstream because there are only so many above a certain pool of income or wealth. Plus, many want to avoid these taxes and find ways to avoid them. If the taxes are not competitive relative to other jurisdictions, politicians risk losing these big taxpayers.

Spending

Outside collecting more in taxes, there is the spending issue.

Cutting spending is hard to do because people rely on that spending for income. Higher spending can also produce more in output when the benefits outweigh the costs (just as lower taxes can sometimes increase overall tax-take).

Depreciating the currency

Inevitably, in countries and empires that have stretched their finances out, they inevitably take the effects through the currency. If a country borrows in its own currency, then it can create money to fill the gap, devaluing it in the process (sometimes relative to other currencies and with respect to gold).

Lowering interest rates helps push money and credit into the system to encourage credit creation. This boosts borrowing and therefore spending. Spending is somebody else’s income. This helps increase financial asset prices, which makes people more creditworthy, which leads to more borrowing, and so on, in a self-perpetuating cycle.

When a country can’t lower short-term interest rates below nominal growth rates (required to get positive growth outcomes), they’ll try to lower longer-term interest rates.

They do this through quantitative easing (QE), a form of asset buying. Buying financial assets increases their prices and lowers their yields.

They’ll buy government debt and government-backed securities (such as mortgage-related securities). If necessary, they can buy corporate debt and other corporate securities as well. They’ll buy practically anything to save the system, even if it means buying stocks.

Currently, more than 60 percent of all global sovereign debt yields less than 1 percent. When rates hit zero and that spread is gone, reducing rates further has little to no impact in pushing more money and credit into the system.

Policymakers can go below zero to try to stimulate more borrowing activity, but that typically doesn’t have any effect on the deposit rate. If there’s no impact on the deposit rate, then there’s no stimulative impact on banks’ funding costs. Thus, there’s no increase in banks’ willingness to lend through that policy alone and there is no influence on the credit creation capacity of the economy and successive output in the real economy.

The ECB, which uses a negative deposit rate, uses open-market refinancing operations (TLTRO programs) to reduce the adverse impact of negative rates on the banking sector by providing cheap financing. The BOJ uses a form of yield curve control to keep a positive spread between its overnight rate and 10-year bond yield positive. These are imperfect solutions.

At a certain point, the primary and secondary forms of monetary policy see diminished marginal impacts and they are better off pivoting to tertiary forms. This is where monetary and fiscal policy must be coordinated. And it needs to be done (and can be done) in a way that isn’t set to the whims of short-term political goals.

This is where the concept of “Modern Monetary Theory” comes in (to use the current fashionable label).

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

Modern Monetary Theory is described differently by different people. Many tend to get overly fixated about their personal conception of how it should look or how certain economic forces work (for ideological reasons or based on their personal experience).

For example, some MMT proponents blame inflation predominantly on the pricing power of businesses. But pricing power is only a small part of it. The bigger determinant of inflation is when you have a shortage of something relative to the demand, causing the price to go up. This is true for labor, goods and services, commodities, financial assets, and so on.

Narrowly defined conceptions of MMT risks missing out on the broader ranges of policy options that are inevitable and can take an infinite number of configurations.

Fundamentally, tertiary monetary policy forms beyond the lower of short-term and long-term interest rates target spenders rather than investors and savers. This is the opposite of both of the main forms of monetary policy we’re accustomed to. This means providing spenders with money and tying it to incentives to spend it.

While such policies that could encompass MMT are controversial to both fiscal policymakers and central bankers, such as forms of universal basic income (UBI) or the buying of land, it ultimately boils down to is whether these policies help produce productivity with the benefits outweighing the costs.

Execution is dependent on having policymakers that are both capable and not politically compromised in terms of doing what’s necessary and effective.

The basic policies have been employed over and over again throughout history, or in different places. But they might sound unique because they haven’t occurred on a large scale within the context of our own lifetimes.

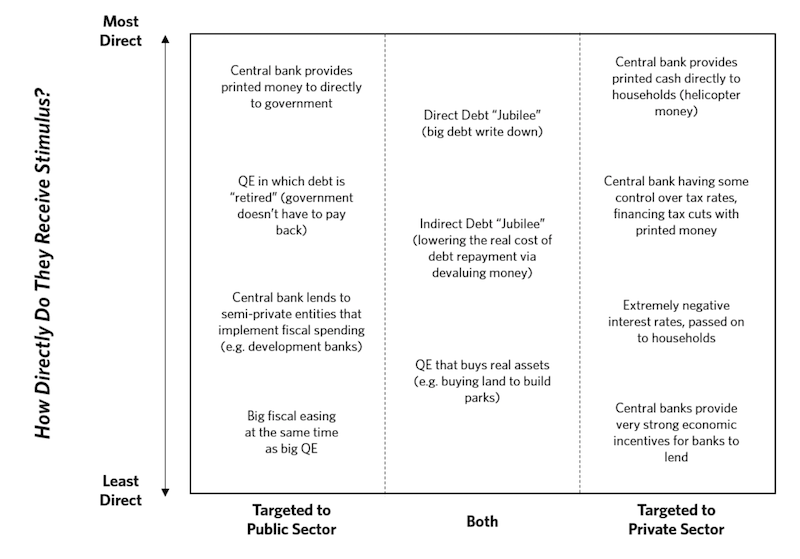

In general, tertiary forms of monetary policy run on a continuum in two basic dimensions:

i) who gets the money (public or private sector)

ii) how directly or indirectly the money gets spent

The more direct methods are more expedient and usually more effective. But they are more difficult to accomplish politically.

Methods that integrate both public and private sector solutions include a big debt write-down (sometimes called a “Jubilee” as a metaphorical reference) or QE programs including the purchase of real estate for public use.

Tertiary forms of monetary policy can include the use of the following elements:

Public Sector options (going from least direct to most direct)

– QE that accompanies a big fiscal easing (higher spending and/or tax cuts)

– Central bank lending to public/private entities that implement fiscal spending, such as development banks

– QE in which the debt that’s purchased is monetized (i.e., debt retirement, where the government doesn’t have to pay it back)

– Central bank provides money to the central government directly

Both (going from least direct to most direct)

– QE that purchases real assets

– Indirect debt write-down through the devaluation of money to lower the real cost

– Direct debt write-down to wipe out part or all of debt owed

Private Sector options (going from least direct to most direct)

– Central banks provide strong incentives for financial institutions to lend

– Very negative interest rates through cash and/or bonds, which are then passed off to households (to encourage spending and borrowing)

– Central banks financing tax cuts

– Helicopter money or universal basic incomes – central bank putting money directly into the hands of households

The chart below can conceptualize the continuum of coordination between monetary and fiscal policies.

As noted, policies of this nature in one form of another has all happened before going back to the earliest monetized economies (e.g., Babylon, Ancient Rome).

While some policy prescriptions might seem novel, these things happen over and over again throughout history, which is why, for economists and market practitioners interested in the “big picture” and why economies and markets work in the way that they do, it is useful to understand them. They can greatly impact various markets.

In some cases, these policies have been pursued in the developed world.

Inflation is generally not a problem in countries where policymakers are simply negating the deflationary effects of the debt service with the inflationary effects of money creation.

Done well, money creation will offset the credit contraction and the output to debt ratio will improve. If done well, the economy will embark on a new positive growth path and ideally GDP/debt will improve in a favorable way over time.

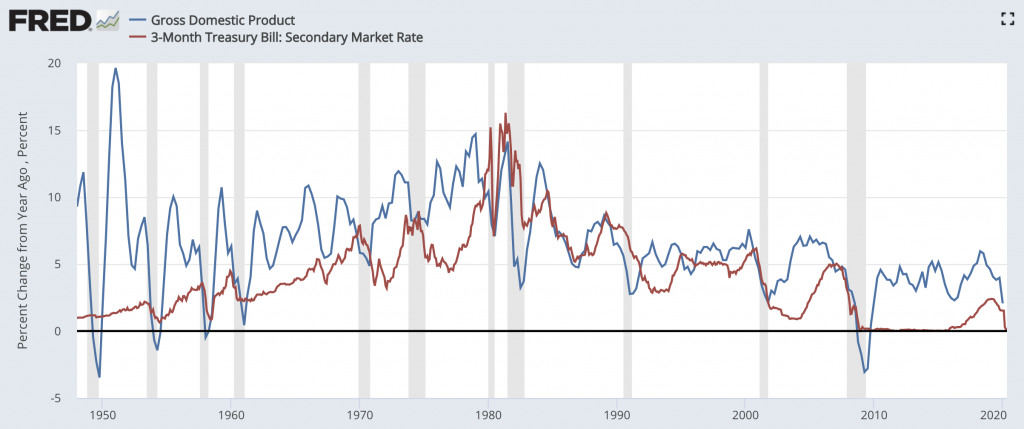

Broadly speaking, when nominal growth rates are above nominal interest rates, the economy will grow faster than the debt servicing requirements. Of course, this is a good thing.

When nominal interest rates exceed nominal growth rates economies eventually run into a problem as the debt servicing requirements swamps the income available to service it.

The diagram below shows a history of the nominal growth and nominal interest rate differential. The blue line is nominal GDP and the red line is the interest rate on cash (i.e., 3-month Treasury bill).

(Sources: BEA, Board of Governors)

In situations where the debts are denominated heavily in one or more foreign currencies and income is earned in domestic currency, then policymakers have much more limited control. This type of mismatch can create problems.

If the foreign currency your debts are denominated in appreciates relative to the currency you earn your income in, that’s effectively like an increase in interest rates.

If the holder of a currency or debt asset sees the asset lose value at a rate that is greater than the interest rate being paid on it, they will lose money.

If it’s expected that this weakness will continue and they will not be compensated with higher rates to offset the price depreciation, the currency will weaken. They will sell it by either moving their money offshore or into inflation-hedge assets like gold or other hard assets.

This can lead to a dangerous feedback loop where foreign denominated debt progressively becomes more expensive to service, leading to more printing of money to fill the gap, and leading to more depreciation (and more expensive foreign debt), in a self-propagating way.

If this type of dynamic emerges, then a country is likely to seek help from the IMF through low-interest loans or will need to figure out an alternative way to get out of their situation (such as a debt default and subsequent long period of austerity).

This currency dynamic is why countries that do most of their borrowing in foreign currencies have inflationary deleveraging processes while countries that borrow in their own currency have deflationary deleveraging processes.

As developed economies become more indebted and monetary authorities find themselves more constrained in their power to help alleviate economic downturns, there comes the question of what comes next with traditional tools reaching their effective limits.

MMT’s basic building block

While Modern Monetary Theory takes different forms depending on whose perspective it’s coming from, a basic building block of MMT is the pinning of interest rates at zero.

Consequently, this means going forward that interest rates will become much more static (in developed markets). Fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP, however, will become much more dynamic and fluid. We’re seeing this already.

Modern Monetary Systems

Broadly speaking, the primary form of monetary goes through the interest rates channel.

Secondary monetary policy (quantitative easing) goes through the credit markets.

Tertiary forms of monetary policy largely run through the currency channel because the rates and credit markets are tapped out when lower interest rates and QE are no longer as effective.

Accordingly, it’s useful to briefly bring up the nature of monetary systems.

There are two basic monetary/currency systems:

i) commodity-based

ii) fiat

In a commodity-based system, the currency is backed by a good that is not subject to large fluctuations in supply and demand. Gold and, to a lesser extent, silver have been the most common backings wherein these goods can be exchanged for currency at a fixed price. It’s a form of fixed exchange rate system.

Money creation under such systems is constrained. To do so, they must either change the convertibility of the commodity to currency or they can go off the system entirely.

In a fiat system, no such commodity backing exists and money and credit growth is influenced by the central bank managing the currency and the incentives of borrowers and lenders to expand credit.

Governments normally prefer fiat systems due to their flexibility.

It gives them the capacity to create credit, influence the money supply, and redistribute wealth in a way that can’t be done under “hard money” systems. However, because of the natural human tendency to prefer near-term gratification over longer-term benefits, such liberal money and credit creation capacity eventually lead to debt crises.

This leads to a mix of measures to alleviate the burden – lowering interest rates, austerity, wealth transfer payments, write-offs, and debt monetization. Lowering interest rates and debt monetization are typically the most convenient, but come at the expense of debasing the currency (though not necessarily in the short-term where the demand for money because of emerging debt problems overwhelms the supply, creating a short-run squeeze).

When this becomes too uncomfortable, governments will typically be forced to go to a different monetary system – either commodity-based (e.g., gold standard) or pegged to a more stable fiat regime (e.g., Ecuador’s dollarization).

Likewise, when the constraints to money and credit creation become too restrictive under commodity-based or pegged systems, these systems will inevitably be abandoned as well.

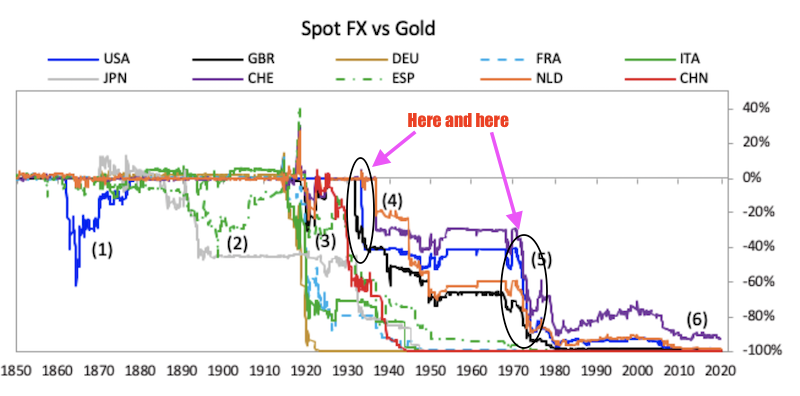

Consequently, over time, governments will cycle between the two systems given the imperfections of each.

Nonetheless, monetary systems tend to work well for long periods. Central banks control money and credit growth by adjusting policy such that major changes in currency regimes are made infrequently.

Most investors underemphasize their currency risk because they haven’t personally experienced it in their lifetimes. While those who follow the financial news hear of cases like Venezuela and Zimbabwe and their currency problems, most assume those are idiosyncratic to poor nations with bad rule of law, and can’t happen in their own countries, particularly in a place where there’s a reserve currency.

We commonly experience recessions once or twice a decade that reminds us of the risk of overly concentrating in an asset class like stocks. But because currency problems tend to emerge after decades of the system working well, most investors underestimate the risk of currency volatility.

When the rates and credit channel for easing monetary policy become maxed out, then currency moves must necessarily become larger if economic volatility is to be avoided.

This doesn’t always mean that one currency will decline relative to another. Central banks can limit appreciation versus another currency to avoid disadvantaging itself in the global export market, for example.

But that usually means losing value relative to something like gold, which is a timeless and universal alternative currency.

When big currency devaluations happen, they tend to be episodic and not gradual. They also tend to go hand in hand with big debt crises because devaluation is a natural consequence of the need to ease debt burdens where printing money is the most painless way.

Within the past one hundred years, the US had two major devaluations in 1933 and 1971 and a more gradual one from 2000 onward.

It hasn’t yet cost the US its reserve currency status.

Many investors include gold in their portfolios to help diversify their portfolios to different currency regimes beyond fiat systems. It is simply another currency that is nobody else’s liability.

Final Thoughts

There is not much that’s really modern about Modern Monetary Theory.

It simply means monetizing debt problems in some form or giving the central bank greater authority over participating in spending and investing programs. When a country gets into debt problems, it can create money to relieve them. Your constraint therefore isn’t necessarily the debt (like it is for entities, like individuals and corporations, that can’t create their own money), but inflation and deprecation in the currency.

The process by which countries, nation-states, and empires get into debt problems and decline has had the same basic causes and effects for thousands of years. Historically this has all happened before going back to the earliest monetized economies. It seems like a novel situation because it hasn’t happened in our lifetimes or in our society.

If income didn’t rise above productivity and debt didn’t rise above income, these issues would be virtually eliminated, though human nature being what it is, it’s impractical to never run into these problems.

Monetary policies one, two, and three

“Monetary policy #1” (short-term interest rates) has no room to run in most developed economies.

“Monetary policy #2” (asset buying) is less effective when spreads begin to close – i.e., spreads further out on the yield curve compress to zero, like the case in Japan and Europe and now the US. When spreads are compressed the marginal impact is diminished and won’t stimulate demand.

So, MMT is fundamentally about coming up with a third form of policy.

On one side of the spectrum you have what some today call “helicopter money” where the government puts money in the hands of spenders and ties it to spending incentives. More generally, it’s the concept of a central bank adopting the power to engage in fiscal policy.

The goal would be to break the relationship between spending and borrowing. That means circumventing the financial markets.

On the other side, you have debt monetization. When fiscal spending exceeds revenue taken in, that produces debt. One way to relieve debt is to pay it in nominal terms assuming it’s in your own currency by simply creating the money. This comes with a devaluation of the currency, holding all else equal.

In many countries, including the US, bond issuance funding deficits is currently what’s written into the laws. Those would need to be changed or they could circumvent it through another transaction.

Different circumstances call for different policies

The idea of this article isn’t to necessarily say which forms of policy are best. All situations are different and there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Different countries different economic, legal, regulatory, political, and cultural norms or hurdles than could influence their policy approaches.

Moreover, many policies will not fall perfectly into one category or another. Quantitative easing, the standard second form of monetary policy, can be integrated in with third forms of monetary policy and can vary in how directly its applied and whether it goes through the public or private sector.

The US Great Depression of the 1930s had elements of many different approaches – e.g., large debt and asset write-downs, purchases of government debt, direct transfer payments, and government-sponsored jobs programs.

A government providing direct payments to spenders is a form of monetary policy. But it can exist without the central bank funding it and instead going through fiscal policy.

Moreover, if lawmakers lower taxes in some way, it’s not helicopter money. But if the central bank underwrites the loan or provides the funds to pay for it, it’s an indirect method of it.

What is generally true is that monetary and fiscal policy coordination is most effective when the programs both make the money and credit available and effectively encourage people to spend it. One person’s spending is another person’s income.

Metaphorically, the relationship between spending and income is like a flywheel. They can feed off each other in a positive, self-reinforcing way. If spending increases, people’s incomes go up, which makes them more creditworthy. People with good uses of loanable funds make quality investments with it to increase overall productivity and drive forward living standards. This increases incomes and spending further.

It’s hard to get that momentum going if the money, credit, and income (the three basic sources of funds) aren’t getting into spending, and instead are being saved (with no lending or spending outlet) or converted into financial asset purchases that don’t finance spending.

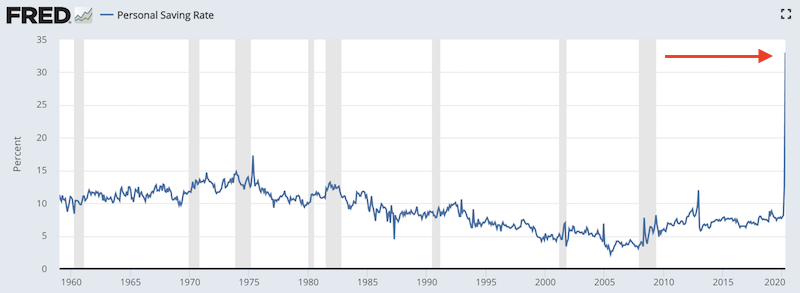

For instance, if the government wants to issue direct transfer payments to individuals (i.e., helicopter money), but there is a lack of incentive to spend the money, then the result is likely to be below expectation.

In the midst of bad economic crises and coming out of them, people are typically more cautious and want to save more.

(Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis)

This is why many believe that any form of universal basic income or helicopter money (in the many ways it can be formed) should be tied to incentives to spend it. This could include having the money disappear if not spent after a certain period of time (e.g., six months).

To make the money and credit available and used toward spending, it means coordinating monetary and fiscal policies and in a way that is done well and not impaired for political or ideological reasons.

If monetary authorities want to stimulate the economy by easing policy but fiscal policymakers are trying to run a tighter budget, then they run the risk of offsetting each other or simply being ineffective.

Central bank independence is of paramount importance. It’s not optimal for the economy to be run with short-term political goals in mind. At the same time, central bankers need to be capable and have the ability to do what’s best in light of its current conditions.

But this also means coordinating monetary and fiscal policy can be difficult. It is usually up to each side to recognize what is the right thing to do independently and coordinate in a de facto sense.

Moreover, it’s also useful when monetary policymakers can not only influence the supply and prices of credit, but can target where they want the stimulus to flow to and who they don’t want it to flow to. For example, the aforementioned stimulus check disbursements tapered off at an annual gross income level of $75k and eligibility was removed after $99k.

If some portions of the economy are problematic in the form of excess indebtedness or speculation, central bankers can use macro-prudential policies (to the extent they exist) to differentiate between separate parts of the economy that are in different states or on different trajectories. They can then more directly target specific parts of the economy to stimulate.