Special Drawing Rights (SDRs): The Alternative Money?

The US dollar is currently the world’s reserve currency. But throughout time, this changes. Various people have different opinions. Will it be the US dollar (USD) for a long time yet (i.e., the rest of this century)? Will sovereign governments become so over-extended that it inevitably reverts back to a hard backing as it’s done for periods over thousands of years? That typically means something like gold, and to a lesser extent silver, a commodity whose supply isn’t subject to large swings. Or will it be a hybrid currency, such as the IMF’s special drawing rights, also known as SDRs?

As of 2020, the US Federal Reserve has a type of “weak monopoly” on the global money creation process. The USD is used globally across a variety of functions, such as foreign exchange reserves held by central banks and sovereign wealth funds, import invoicing, international debt, and global payments.

About 60 percent of the world’s reserves are in US dollars. The Fed has had the ability to put money and credit in the hands of those who need it to stabilize the economy and markets (though naturally imprecisely and slowly).

But given the Fed is the US’s central bank, these dollars are mostly going to US entities. Nonetheless, the amount of dollars owed globally are about 4x higher internationally than they are in the US. That squeezes a lot of individuals, corporations, and governments internationally. This is particularly true when they earn their income in their domestic currency while owing in dollars (or any foreign currency). When the foreign currency goes up relative to your domestic currency, they get squeezed.

Yet with the US’s long-term financial situation, there’s the risk of endangering its reserve status. In the end, you can only consume what you produce. Producing too much currency and debt may help with what needs to be done today to fill in the funding gaps, but it creates new IOUs that will never be paid.

In the beginning of a new debt cycle (different from the standard business cycle), when there are few debts, these countries tend to be large borrowers. As this goes on, average interest rates across the cycle tend to drop as governments become more indebted. New political leaders and central bankers have to contend with these growing issues of how the economy is going to service its debts at the same time there’s less room left to stimulate the economy.

Moreover, when big debtors fail, governments are forced to bail them out when letting them fail would be costlier altogether than saving them.

Governments eventually get themselves into big problems that are much larger in magnitude than those experienced by individuals, corporations, and other entities.

Namely, the government becomes a large debtor and essentially bails itself out by creating money and credit and in the process devaluing it (not necessarily in the short-term if there is the demand for it).

Politicians are also remembered not on the basis of how much they were financially savvy (e.g., balancing budgets and the like) but on how much they spent. It is easy for rulers and politicians to run up debts that won’t come due until long after their reigns or terms are up, making the allure of doing so easy. It’s then up to those who come after them to deal with an increasingly indebted situation where there’s progressively less room for error.

And inevitably, governments will always choose to create money over the alternative of allowing a lot of defaults and financial pain.

There are three main ways countries deal with their financial problems:

i) cut spending

ii) higher taxes

iii) print money

In any huge funding gap created by a crisis, you can’t shore up your finances through austerity or tax hikes. If you try that, it won’t accomplish much at the scale required. If you’re a politician, you know that providing the money and credit required to fill in the gaps is the most important thing even if, over the long-run, the debt and long-term obligations that spending created won’t be paid back.

So, they inevitably go with the third (printing money) if they can. And for the US, it’s a no-brainer if you have the world’s top reserve currency, though if your finances are bad and you’re technically insolvent on an asset/liability basis, then you’re at risk of jeopardizing that.

This is ultimately a currency question. What is the value of money?

Does the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights hold any promise?

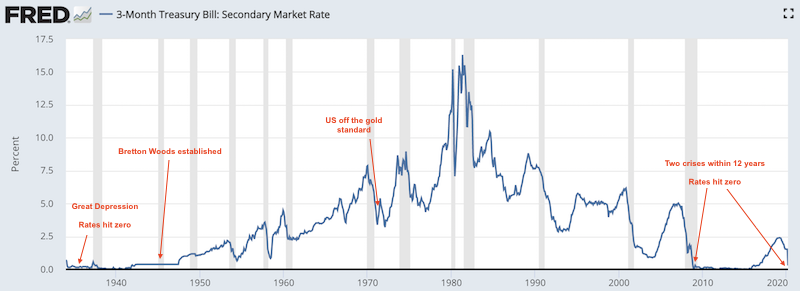

Debt crises come and go. There was the Great Depression and then World War II, which brought forth the Bretton Woods system (1944) that established the US as the world’s most dominant superpower and the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

That lasted until 1971 when the US dropped the gold standard. Inflation problems in the US ensued for the next decade as monetary policy was run too loosely. Starting in 1981, each cyclical high and each cyclical trough in interest rates has been lower than the previous one.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

With less stimulant available, each successive widespread bailout comes at a cost.

First, lowering short-term interest rates was the main way of stimulating credit creation. During the Great Depression and again in 2008, lowering long-term interest rates, also known as quantitative easing (QE) became a secondary way of doing it. That eventually ran out of room as longer duration assets also saw their spreads getting squeezed relative to short-term interest rates.

After that, like we’re doing now, there’s coordination between fiscal and monetary policy with credit guarantees, direct payments, among other programs. This is the third form of monetary policy.

While the Fed can simply create money, this comes at a cost, even if it’s discreet and not well appreciated.

Countries can bail themselves out. But they pay for it, long-term, through the currency channel.

Several weeks ago, the US Congress passed a $2.2-$2.3 trillion recovery package called the CARES Act. It included $350 billion in small business loans, which can be forgivable if it helps pay employees. The funding dried up quickly due to demand.

Also within the law is $425 billion for the Treasury to recapitalize the Federal Reserve. The Fed is a central bank (the bank of the commercial banks) and operates similar to a bank, so it will leverage this new capital into buying other forms of collateral to help support the recovery, including corporate credit, mortgages, municipal bonds, and other assets.

For countries with limited demand for their currency (and accordingly low demand for their debt), they are turning to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At least 120 countries have reached out for help to the organization, which has about a $1 trillion balance sheet outside its liquidity buffer.

Turning to the IMF = Printing of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)

Special drawing rights (SDRs) are a composition of various reserve currencies globally:

USD: 42%

EUR: 31%

CNY: 11%

JPY: 8%

GBP: 8%

Special Drawing Rights are a unit of account and not necessarily an independent currency. The weightings and currencies used are based on the amount of reserves held in the currency globally and the level of international exports conducted in them. The basket (i.e., both weightings and currencies) can be re-evaluated every five years. The renminbi was added in November 2015 and effectuated the following October.

In 2008, SDRs were used to a relatively small extent (about $250 billion). It also took a long time to issue them (August 2009), after the crisis had already blown past and nearly a year after the worst part.

In recent years, more of the world is turning to the IMF for help, which means greater de facto demand for SDRs. However, the world had also never been so indebted. The balance sheet problems become magnified when income drops.

Countries with reserve currencies can create the money, but it also means starting the recovery from a high debt base, which makes it harder to increase government spending and increase tax takes during the ensuing expansion. It also means a lot of near-term pain when creditors don’t get paid and companies can’t meet their expenses, leading to asset sales, defaults, and falling financial markets.

Creating SDRs normally involves IMF members issuing them in proportion to their voting rights in the IMF. But this also means countries like China and Iran, which have tension with the US, would also be part of any IMF bailout package. This is part of the reason why the US doesn’t want new SDR issuance.

Pressure on the IMF grows as any crisis deepens or begins to increasingly affect new countries.

The issue has no limitations on printing money in theory, but it’s not costless at the same time. This leaves more pressure on the IMF and its own printing exercise, particularly when its jurisdiction is larger with the Fed providing direct recourse to US individuals and companies only.

China may have its own conditions for accepting IMF money, such as a reduced role of the US dollar in the SDR. China is already 11 percent of the SDR (largely because of its role in global trade) despite being only 2 percent of global reserves.

Can special drawing rights be the next reserve currency?

Special drawing rights – a type of hybrid currency of existing national currencies – are not likely to supplant the US dollar as a top reserve currency despite the IMF’s technical status as the lender of last resort.

Usually the country with the highest national income has the world’s top reserve currency. This also typically means they have the world’s most powerful military and are technologically superior in most other ways.

But we’re in a world where the total debt is now over $300 trillion. Taking into account about a 20 percent drop, debt obligations are now about 4x global annual income. If you take into account the debt-like obligations on top of that in the form of pension, healthcare, and other unfunded obligations, it’s much higher, depending on the discount rate used to capitalize these obligations. But in the US alone, you get non-debt (but debt-like) obligations that are north of $300 trillion alone.

These obligations – much of which involve entities receiving something without producing anything – are inevitably a money printing exercise. The amount of income extracted at the federal level doesn’t pay for spending, let alone the increasing wave of obligations coming due.

Ultimately, it’s a confidence game. Currency and debt are IOUs. Too many IOUs inevitably leads to crises.

Throughout history, governments choose commodity-based currency systems only when they’re forced to because unconstrained monetary systems led to them “printing” a lot of it to service their debt burdens. They inevitably abandon commodity-based systems, or change the conversion when they don’t permit the level of money creation required in crises. So, governments oscillate between the two over time. Nonetheless, currency regimes tend to work successfully for decades, or sometimes for more than a century, which means these watershed moments are not reached frequently.

This is why many investors use gold as a currency hedge against real rates becoming unacceptably low and as an antidote against the types of tail risks that happen rarely (e.g., shifts in currency regimes). But they do occur over and over throughout history and frequently enough for investors to hear about them in select countries semi-frequently (e.g., Venezuela, Zimbabwe).

Final Thoughts

Central banks that have the privilege of having reserve currencies can “print” money. Central banks without reserve currency countries have limited capacity in that regard due to limited demand for their currencies (i.e., the debt the money printing creates).

There is massive demand for IMF support, with over 120 countries requesting aid from the organization as a source of capital, especially for countries with low reserves. The IMF has its own currency (more realistically a unit of account) called Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). Even as the global lender of last resort, its unit of account is not likely to supplant the US dollar as a reserve currency. It’s not a currency on its own, but rather comprised of other national currencies.

Reserve currencies can last past the point of when nations and empires thrust themselves into poor long-term economic health. There’s a reputation component. And incomes can remain high even if the country is in bad shape in the long-run from an asset and liability perspective. The US will never be able to attend to its debt and long-term obligations. They can never cut spending enough or tax enough, as there are constraints to these processes. They will need to print money. There won’t be enough demand for the debt domestically or abroad, so the Federal Reserve will need to buy it or directly monetize it (basically not issuing debt in the first place or retiring it).

Throughout history, countries oscillate between commodity-based monetary systems and fiat monetary systems because of the problems associated with each. In the former case, money creation is dependent on increasing the supply of a commodity not subject to large swings in demand (usually gold) or by changing the conversion rate of said commodity to money. Because the constraints to money creation are too onerous under this approach, after some time operating this system, nations abandon it in favor of fiat regimes where they can create as much as they want, inevitably leading to debt problems.

While reserve status is fleeting – tending to last 75-150 years usually – something like gold as a type of alternative money tends to have lasting demand over centuries. It is by no means perfect and has an environment is which it does well and an environment in which it does poorly. But holding it in a smaller quantity as a type of alternative cash can useful as part of one’s long-term holdings.