Low Interest Rates: How Do They Create Wealth?

This article was published on July 31, 2019

The developed world is awash in low interest rates and is about to get rates that are even lower. Traders look heavily toward the US Federal Reserve and other central banks for clues on where asset markets will go. This has been covered in other posts on the blog, such as “Why Day Traders Need to Pay Attention to Central Banks”.

As the biggest contributors to money and credit creation in the world economy, the Fed is heavily followed by almost all market participants. Its meetings, actions, and proposed policy prescriptions have tangible effects on financial markets.

But what often isn’t clear is how exactly low rates stimulate wealth creation. There’s the following chain of logic:

- Central bankers see signs of weakening growth and/or inflation, which leads to

- Interest rates being reduced, which creates

- Economic stimulus (lending becomes easier), which leads to

- Stronger economic growth when the returns generated from the debt exceed its cost, which helps to generate

- Higher corporate profits, which in turn leads to

- Higher stock prices, which causes

- Higher wealth (at least among those who own stocks and other financial assets that benefit from Fed stimulation, or benefit from the positive influences of such policies, such as companies’ higher proclivity to hire when project hurdle rates can be more attainably met)

What are the specific channels that low interest rates benefit?

1. Lower interest rates make capital cheaper. This encourages businesses to invest because it reduces the hurdle rate necessary for their projects and other ventures to be economically viable.

For example, if a project is expected to produce annualized returns of 5 percent going forward, but debt or equity funding costs more than 5 percent, the project isn’t feasible and will never get off the ground in those conditions. The economy won’t gain whatever benefits accrue from building out the project.

However, if the central bank lowers rates and this feeds into lower capital market rates that companies borrow at, then more projects and initiatives become feasible and this helps unlock more economic growth.

2. To help companies accomplish these objectives, they need to hire more. As more people are hired or find jobs where they will be more productive, the economy is able to operate at a higher capacity. This is true until it “overheats”. This is the point at which workers have bargaining power for higher wages, which leads to wage inflation. This helps to encourage consumer spending.

3. If companies have lower debt servicing burdens from lower rates, this helps increase their profits. Higher net income gives them more cash to reduce debt, buy back stock, issue dividends, or help them engage in capital expenditures to grow their business.

4. As rates fall, this increases the value of financial assets through the net present value effect. This makes companies worth more. Accordingly, investors are more likely to give them capital. Or investors can realize gains on their holdings in the company by selling. This can then go back into the economy in the form of spending or other investing.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, declining interest rates have been the primary factor behind rising asset prices.

It is also a factor behind the rise in global populism in both the US and Europe. Those who have owned financial assets have by and large done well financially and seen their net worths rise. Those who haven’t owned financial assets or only marginally been involved have been heavily left behind. This has produced a wealth gap and contributed to increasing friction between what we can broadly call “investors” and “workers” and has had some effect in driving recent political movements.

5. Lower rates have produced cash rates of zero percent, less than zero, or just above zero throughout the developed world. The lack of return on cash or short-term bonds has pushed investors out over the risk curve into riskier assets like equities.

This has also broadly increased risk tolerance in the financial markets and given capital to companies and ventures that would have otherwise never gotten off the ground or survive without this support. As a result, due to the abundance of capital, about 12 percent of the world’s companies are considered “zombies” – meaning the interest payments on their debt exceed their operating profits. If this is anything but temporary, these businesses are not viable and would cease to exist otherwise. In the early 1990s, this rate was estimated to be around 2 percent.

6. Lower rates help consumers. At the household level of the economy, most will buy houses and cars partially using debt because of their large cost relative to their income.

The demand for these items is therefore heavily dependent on the supply and demand for credit. Low rates also help consumers refinance existing mortgages and other debt agreements. Monthly payments on floating-rate mortgages decline. This gives households higher disposable incomes and more money to spend on discretionary purchases or lead to higher savings rates. (The propensity to spend is likely to increase more than the propensity to save as rates fall because of the lower return on savings, though the economic theory and empirical evidence isn’t clear-cut.)

7. People tend to extrapolate the past. So, when interest rates are falling, people expect this to continue. This makes all of which was discussed above perceived to be likely to continue going forward.

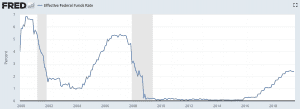

For example, in the Fed’s interest rate cycles, they almost never raise or lower rates randomly. When interest rates are rising, they typically raise incrementally over a sustained period, with several adding up to a multi-percentage move over time. Likewise, when rates fall, they also tend to have a path of an extended run in one direction. This is also true in emerging economies, but with more variability given developing economies are more volatile in their growth and inflation patterns, so naturally interest volatility is higher as well.

However, rates tend to be cut faster than rates rise. This is because an easing cycle is often in response to a downturn in the economy.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System)

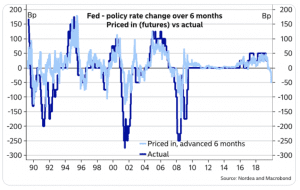

Traders also typically tend to underestimate the extent of Fed easing going by market pricing versus what actually transpired six months laters.

Political Pressure for Low Interest Rates

In the US, President Donald Trump has been pressuring the Fed to lower interest rates. Central banks, particularly in the developed world, pride themselves on political independence as this helps in forming better policy rather than responding to political whims and narrow self-interests that may not be in line with the greater good.

Though it seems unusual for Trump to try to exert political influence on the Fed, it is not new. Though the last three US presidents have steered clear of outwardly commenting on the Fed – Obama refrained, George W. Bush refrained, and Bill Clinton considered the tactic but also refrained based on the advice of his advisors – politicians come to realize that the Fed largely has more control over the economy than they do. The central bank can respond faster to economic events and without the partisan wrangling that accompanies fiscal policy decisions.

In some fashion, fiscal and monetary policy is already coordinated in Japan (an economy with very low growth and inflation) and China (still heavily a centrally managed economy) to make sure each other’s actions don’t cancel out.

Why, specifically, does Trump want lower interest rates from the Fed?

1. Trump is heavily focused on being re-elected. Since lower rates generally help support economic growth and typically go hand-in-hand with a rising stock market (and other asset prices), both of which contribute to increasing one’s re-election odds, getting lower interest rates will help him achieve this goal.

If his primary aim is re-election he may be less vocal about wanting lower interest rates following November 2020. Though lower rates may still be a point of interest for him in order to help the economy throughout his prospective second term and for legacy reasons.

2. Trump has been a real estate executive for most of his life and real estate is heavily about obtaining cheap leverage. Therefore, to Trump, lower rates are hardwired as always a good thing in helping him in his business and political affairs.

The negative effects of low rates

So far, this article has mostly posited the favorable view of lower interest rates. In the current situation in developed market economies, the risks to the global economy are skewed to the downside. This is because the world has a lot of debt relative to income (debt markets total to over 250 percent of global GDP). Therefore, it doesn’t take much to slow the economy down by raising interest rates even a little bit with the impact it has on debt servicing requirements.

However, there are times when low rates are not in the best interests of an economy and can be harmful.

1. As low rates are stimulative, there is such a thing as low rates being overly so. The primary concern is undue inflationary pressures. Some inflation is considered a positive thing and a foundational central banking practice. It is set to a low, positive target (often a symmetric target so it is not viewed as a ceiling). Or it may be formulated as a range, such as the Reserve Bank of Australia targeting an inflation range of 2 to 3 percent. When inflation is around this target it is viewed as a healthy aggregate measure for trends in output, wages, spending, and employment.

But too much inflation can lead to excess wage inflation, which leads to higher prices for goods and services by placing too much pricing power in favor of those who sell them. For savers and those who lived on fixed incomes, their costs will rise in excess of their incomes. While more well-off households can invest in assets that help offset the rise in inflation – e.g., inflation-linked bonds, real estate, equities, some commodities – lower-income households that lack disposable income largely cannot and are disproportionately affected.

For those close to retirement or in retirement, they will emphasize more conservative investment vehicles such as cash, money market accounts, or safe fixed rate government bonds, these instruments will be affected through lower real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) returns. Cash is typically a poor investment after considering the effects of both inflation and tax on the interest. The return, in real terms, is often negative.

Increasingly in some economies, which pay nothing on bank deposits or charge a negative interest rate plus additional surcharges, the nominal return (i.e., including inflation) on cash savings is often negative.

2. When rates are low, this leads to the greater availability of cheap credit. This leads to more leverage and investment in companies or pockets of the economy where the long-term return from the investment isn’t likely to justify the cost of capital.

Lenders determine how much they can lend based on the net income or projected net income of the borrowers, collateral (net worth), and their own capacities to lend.

In rising economies, all these rise together, which is not sustainable. Debt growth increases faster than the incomes and liquid assets available to service the debt. Borrowers feel rich because of their access to lenders and on aggregate spend more than they earn and buy assets at high prices with leverage.

When low rates lead to bubbles, it is usually most prominently in one or two particular areas. And these often go on under the radar because it’s concealed beneath the macroeconomic averages that make markets and economies look otherwise healthy. We have a natural tendency to extrapolate the past and assume current conditions will continue into the future. In lending and borrowing situations, this often creates reckless lending practices that results in an accumulation of bad loans.

Bubbles become increasingly more apparent when an increasing amount is being borrowed to make debt payments. Of course, while this might provide a short-term fix and give some buffer room to deal with the economics of their situation, it exacerbates the indebtedness of borrowers. At some point, this becomes recognized by market participants, bankers, and policymakers. They begin to slam on the brakes by tightening lending standards and central banks will often increase rates as a blunt tool.

When money and credit growth is diminished and borrowing becomes more difficult, credit growth declines, which in turn reduces incomes and spending. (Remember that one person’s borrowing is another person’s income and higher incomes tend to lead to greater borrowing capacity.)

Because of this, more debt services problems come to the surface when the process works in reverse. At this point, we are likely at or around the top of the debt cycle. This is the point at which debt servicing costs are greater than the amount that can be borrowed to support spending needs within the economy.

When central banks recognize that credit growth is too fast, they will typically hike interest rates. This typically accelerates the drop in lending, incomes, and spending. Not only will lending slow, but borrowers’ need to make due on their payments increases. Those with unhedged floating-rate obligations will see their interest payment increase directly.

Risk assets such as stocks will typically top. This leads to a self-reinforcing cycle where there is less lending and less spending. Moreover, there is also less collateral value available to pledge toward new loans. Net worth values decline, and leads to even lower levels of lending and so forth going forward, and leads to trends in asset markets – typically down for risk assets and up for the safest assets, such as US Treasuries and alternative safe havens like gold.

When debtors cannot service their debt to lenders, these lending institutions now face the quandary of not being able to meet their obligations to their own creditors. When this happens, central bankers and other policymakers must directly work with the lenders first.

The more leveraged the lender is, the more precarious their situation when involving defaults at any non-trivial level. Lenders most exposed to the debt issues pose the greatest risks for creditworthy borrowers and the broader economy. Usually, these lenders are commercial banks. However, credit providers in an economy are now a more diverse set of institutions than they have been traditionally, and include non-bank lenders in various forms, such as insurance companies, broker-dealers, special purpose entities, among others.

3. Low rates can enhance investors’ proclivity to reach for yield in both a relative and absolute sense. In a relative sense, there’s a risk premium between cash, bonds, and stocks.

Traders and investors expect to be compensated for taking on more risk. Bonds, depending on what type of bond, will typically yield about 2 percent more than cash over the long-run. Equities will require an extra 2 percent more than bonds, also depending on the type of bonds and the idiosyncratic risk characteristics of the particular stock.

When the yield on cash is very low, this helps to elevate the premium between cash and bonds and bonds and equities. This helps bid up the price of financial assets and create wealth through the financial system. For those who own financial assets, this is great. For those who don’t, it may be less beneficial, though may still help when companies become worth more, have lower hurdle rates for projects to become profitable, and need to hire more.

In an absolute sense, even if the risk premium between cash and equities is normal, say 4 or 5 percent, but cash returns zero (negative in inflation-adjusted terms), investors have no other alternative in terms of how to generate positive real returns. The equity risk premium could compress more and the only outlet for positive real returns would still be in stocks.

This can create undue risk taking and create purchases of financial assets on leverage. When financial assets are bid up, this reduces their forward expected returns, and thus their yield. When yields aren’t sufficient to cover the debt they’re paid with, these investments are underwater.

For example, in private equity, real estate, and other asset markets, companies are often purchased with 25 to 35 percent equity and 65 to 75 percent debt. When these assets eventually come down in value by 25 percent or more, this leads to negative net worth. At a broad enough level this bleeds into creditworthiness and lending behavior.

4. When interest rates are low, central banks lack the potential to stimulate the economy through the traditional rate cutting channel. Central bankers have the most experience and historical data available with respect to using overnight/cash rates as a policy setting tool. When venturing into new policies, they will have less empirical information by which to go by. This, to some extent, increases the probability of a policy mistake. In some cases, not only will they lack the firm understanding of the effects and ramifications of such a policy prescription, but will lack the authority to do what they believe they need to do in the best interests of the economy (e.g., political interference, legal obstacles to implementation).

In the US in the 1970s and into the earliest part of the 1980s, central bankers chose to run inflation a little higher than typical in order to squeeze more growth out of the economy. But this turned out badly, as price pressures and inefficiencies exceeded whatever incremental effect was made on growth. Higher labor costs stemming from an overheated job market can squeeze margins to the point where this leads to a decline in business investment and subsequent hiring.

Conclusion

Lower rates typically follow central bankers’ observations that growth and/or inflation is weakening in any economy. This is a form of economic stimulus. Lending is incentivized, which leads to stronger economic growth, which helps in hiring, which helps corporate profits (when labor among other inputs is favorably and competitively priced), which helps stock and asset prices, which helps create wealth.

On the flip side, low rates can lead to very undesirable outcomes. It can come in the form of an overheated labor market, where wage inflation leads to much of the market pricing power falling in the hands of the sellers of goods and services (in order to maintain their margins).

It may involve cheap and abundant leverage leading to excess speculation on financial assets. This can include stocks (e.g., 2000 tech boom), real estate (1989-1990, 2007-2008), and or even high-yield bonds (also part of the 1990 recession experienced by many parts of the developed world).

Low rates can lead to bubbles forming in one or a small number of sectors that threaten an economy’s financial stability. Banks and policymakers may miss the warning signs, such as an increasing amount of debt being used to service pre-existing debt, which only compounds borrowers’ indebtedness. Or they may too eagerly assume that the recent past may be like the future when it becomes increasingly clear that the investments being made with the debt won’t throw off the cash flow to service the liabilities in the future.

Understanding what’s going on at the broader macroeconomic level and how this will affect trends in your traded asset classes can have a big influence on your eventual results. You’ll also be able to characterize what’s going on in the economy and markets in a more cohesive, simplified manner rather than viewing everything coming at you as a befuddling mish-mash of various unrelated things.