This article was published on January 26, 2021.

There is a new paradigm in monetary and fiscal policy. This has implications for investing in a zero interest rate environment.

For a brief refresher, there are three broad categories of monetary policy (which has been covered in other articles in more depth).

i) Adjustment of short-term interest rates. Once you get those to zero or a little bit less to somewhat negative, they’re no longer stimulative because the incentive in the private sector to lend and get money and credit into the system isn’t there.

ii) Adjustment of long-term interest rates. Long-term interest rates are embedded in longer-duration securities like bonds. To lower long-term interest rates central banks will “print” money (i.e., which is just electronic money creation) and buy bonds. This is often called quantitative easing (QE) or sometimes, simply, asset buying.

They’ll start with government bonds, and if necessary go down the quality ladder to corporate bonds and even stocks or equity-like securities.

The spreads on these can be pulled down relative to cash rates such that it’s no longer stimulative. When that’s out of room – like it is in all the main three reserve currency parts of the world (the US, developed Europe, Japan) – they have to move on to a third form of policy.

iii) Joint fiscal and monetary policy. When the first and second forms of monetary policy are out of gas and there’s a problem rectifying income, spending, and debt imbalances, central governments will move to a coordination of the main two levers of policy.

The money and credit isn’t getting to where it needs to go, so it stimulates a need for this.

This can take a variety of forms from monetizing deficits directly (e.g., central bank giving money to the government directly) or participating in direct spending and consumption programs (e.g., helicopter money).

Combinations of two or more of these three approaches

There are also combinations of these various approaches.

Take yield curve control, for example.

It is similar to QE because the central bank is buying bonds and other fixed income securities.

But the difference between QE and YCC is that QE has no specific bond yield target in mind while YCC fixes the rate at a certain level or range.

With QE, the central bank will commit to purchasing a certain amount of bonds or securities to support asset prices to help with that positive feed-through of lower long-term interest rates into the economy.

Yield curve control has a specific bond yield in mind on one or more parts of the curve.

YCC makes it so that the central bank will make the purchases it needs in order to effectively guarantee the yield rather than simply being an influence on them. This is done to ensure that large government deficits can be financed without interest rates increasing.

QE will take a policy approach that commonly works by buying a certain amount of securities per month or within a certain timeframe.

YCC, on the other hand, will operate by coming into the market automatically on an as needed basis to buy or sell a certain amount of securities to maintain a specific yield.

Many policy approaches don’t fit exactly into each of the three main categories. They have elements of more than one of them and run along a continuum.

For instance, if the government provides a tax break, that’s not “helicopter money” (central bank putting money in the hands of spenders and providing incentives to spend it). But it depends on how it’s financed.

If the central bank is monetizing the extra fiscal deficit from a tax break, it could be considered a form of helicopter money. Namely, if the government is distributing the money with the central bank financing that spending without a loan, then that’s helicopter money through fiscal channels.

Money and credit drive markets

Money and credit are what drive markets.

The two main levers for how money and credit are pushed into the financial system and move markets are monetary and fiscal policy, so it’s important to understand them.

In the US, and practically all of the developed world, we’re now onto the third form of monetary policy. Short-term interest rates are at zero or even negative in some cases, and long-term interest rates have been pulled down to close to zero or sometimes negative.

So, to make the system work, fiscal and monetary policy needs to be coordinated to get the money and credit in the hands of those who need it to “save the system”.

Fiscal policy, though it has the disadvantage of being a political process, directs the resources and monetary policy comes in to provide the liquidity and prevent interest rates from going up to avoid offsetting the types of things that need to be achieved.

The range of these policy options is discussed in a separate article.

The new monetary paradigm

There is now joint fiscal and monetary policy.

This third form of monetary policy is simply to get money in the hands of spenders to make up for lost income to avoid an elongated depression in economic activity.

The byproduct of this policy is that there are zero to near-zero (or negative) interest rates across the developed world.

That means for most investors in developed countries who are focused on their own domestic markets, cash and most forms of quality bonds are largely not very viable investments from an income perspective.

Fewer people want to hold an investment if it doesn’t yield anything in real terms and even less will hold it if it doesn’t yield anything in nominal terms.

Even the BBB yield, which is one step above junk grade, is only about 2.5 percent.

(Source: Ice Data Indices, LLC)

After inflation and taxes, you’re left with about nothing.

The zero and near-zero rates across the developed world is probably the single most important issue for investors to understand, as they will need to learn how to manage money effectively in this new world.

The old ways of easing policy and having that create a boost to asset prices won’t work to the degree we’ve become accustomed to.

Since 2008, due to the financial crisis, we’ve been used to being around the zero lower bound on interest rates in all the main reserve currency countries.

It was true in the US, the core EU countries and the UK, Japan, Switzerland, Canada, and developed Oceania (Australia, New Zealand).

But the policies central banks undertook to ease was simply lowering cash rates and when that wasn’t enough moving into buying financial assets.

From history, you can see that most economic downturns are related to debt and liquidity. And these are dealt with in one way or another through an easing of monetary policy.

If you go back to the 1800s and look at how governments rectified debt and market problems, they always eased.

Depressions tend to not last indefinitely because in one form or another they figure out they need more money and credit in the system irrespective of what type of monetary system they’re on (i.e., commodity-based, commodity-linked, or fiat).

If they’re on an unconstrained monetary system (e.g., gold-based, bimetallic) and changing the convertibility of the commodity for the currency doesn’t work, they inevitably sever the tie with it.

As for the value of money, it could end up depreciated. And it’s especially a risk when that currency isn’t in great demand globally or a lot of money has been borrowed in a foreign currency, like they commonly do in emerging markets.

But they will always want to ease to get a reflation in activity.

Hitting the zero interest rate bound has never been a hard constraint even if it seemed like a barrier and a novel problem when it happened, like in the 1930-1932 period in the US during the Great Depression and the 2008-09 period after the financial crisis when buying assets to lower long-term rates became the new policy.

Even if nominal interest rates can only go to around zero, the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) interest rates can go quite negative.

On March 5, 1933, President Roosevelt made the announcement of ending the link with gold and depreciating the currency to reflate the economy. That gave banks the money they needed to repay their depositors.

The same type of thing happened on August 15, 1971 when President Nixon said he was unlinking gold from the dollar (the relationship had been previously re-established in 1944 under the Bretton Woods monetary system). There were too many liabilities relative to the amount of gold available and there wasn’t enough gold to go around.

There was the same type of “desperate easing” situation in 2008 with the US Congress and Treasury getting together to create the TARP program and going to quantitative easing.

In 2012, with the debt crisis in Europe, Mario Draghi had a similar type of decision to make.

In the US, the Federal Reserve has created a lot of money and implemented credit support programs with the US Congress.

That’s going into equity assets and various credit assets. You also see some of it going into gold. You could also see a depreciation in the value of the dollar eventually. However, a dollar squeeze and appreciation occurs at the beginning as people have a shortage of money relative to their need for it.

Everything is timing. You see the bond yields fall first (bond prices up), then the currency falls later.

But at the time, you don’t necessarily know which of these various asset class interactions is going to happen or how it’s going to play out.

Back in 1971, there was a large decline in the value of real stock prices (up in nominal terms, down in real terms). Inflation accelerated. Bonds also did poorly. Gold and commodities performed best.

Because of the inflationary 1970s, eventually the Fed had had enough under Volcker, who hiked interest rates (i.e., cash rates) to over 19 percent. This was more than the inflation rate (i.e., real rates were positive), which attracted more inflows into the dollar and out of commodities and gold. It caused a recession but only temporarily, as the Fed eventually eased. This easing gave way to the stock and bond bull markets of the 1980s and 90s. Commodities fell out of favor again in favor of stocks and the quality yields on fixed income.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

It’s hard for most investors to time these shifts.

This is why having balance is key, which we’ll get into more later on.

Cash’s role in a portfolio

Investors are used to thinking of cash as a safe investment.

But in this environment where central governments need to create money and finance very large deficits to stay out of a deflationary depression, investors can’t really sit in an overabundance of cash. There needs to be enough to provide liquidity and optionality, and to be safe from having to sell in a drawdown, but too much becomes counterproductive.

When thinking from the store of wealth concept, cash is not as safe. It doesn’t earn anything, there’s inflation that eats its returns over time. Then there’s also the devaluation aspect over the long-term when printing a lot.

While many investors tend to think of just equity returns, there has to be a level of balance in a portfolio.

Looking over history and finding analogous periods to the one we’re in now (e.g., the 1935-1940 period or another), you can’t be sure if you’re going to see a depreciation in the value of money and common store of wealth (i.e., your own domestic currency).

So, what you define as risk is murky because risk encapsulates many different things. Many have grown accustomed to seeing cash as a risk-free investment because its value doesn’t move around much. But risk isn’t just price volatility.

Cash can be a risky asset because it loses value over time in a stealth way.

So, you have to think about different asset classes and different geographies in terms of having a strategic asset allocation mix.

The one thing you can be pretty sure of is that the Federal Reserve and other central banks are not going to allow an implosion to happen without printing a lot money and doing what they can to save the system.

Risk assets

The forward returns expectations for risk assets, in real terms, is probably close to zero over the next decade. Central bankers won’t want asset prices to be bad in nominal terms, but the likelihood of them being very good in real terms is low. Yet investors will still have to contend with the volatility of owning those assets.

One of the basic equilibriums in markets is that stocks must yield more than bonds, and bonds must yield more than cash, and by the appropriate risk premiums.

Cash yields about nothing currently, or negative depending on where you go, and central banks want to keep it that way to incentivize credit creation and limit borrowing costs. There’s essentially a penalty to owning it.

A 10-year government bond, a common benchmark in any market, yields between 50-100bps as this is written in the US, about zero in Europe (each market is different), and zero in Japan where they practice yield curve control. Those are the main three reserve currency areas.

In China, the other major financial system globally, the 10-year bond is a bit under 3 percent. China has more room to work within the traditional monetary policy framework with standard interest rates policy still effective.

Stocks are priced off the present value of discounted cash flows.

Usually, the yield on stocks is about 3 percent more than the 10-year bond. And this 10-year bond is generally giving you about 2-3 percent more than cash. But cash and bonds are basically now in the same bucket as funding vehicles rather than investment vehicles.

If we look at the returns of US stocks, the US 10-year, USD cash, and gold (another store of value that over the long-run returns a bit better than cash), we can see the following annual returns.

Portfolio Assets

____

Performance statistics for portfolio components (from January 1972-June 2020)

We can also look at the monthly correlations over time.

Monthly Correlations

____

Correlations for the portfolio assets

We don’t expect the returns of equities to exceed that 2-3 percent premium over bonds. The nominal returns you see of the past also aren’t likely to transpire. That was aided not just by interest rate and other easy liquidity policies, but by the higher productivity rates of the past and also employment growth tailwinds (e.g., women entering the labor force, growing working age population) that are no longer there.

Stocks over the next ten years or so are likely to see annual nominal returns of maybe 3-4 percent while still getting the same type of volatility.

Higher returns are also not likely to manifest in private equity or venture capital. They provide a little bit of a premium over stocks being riskier and less liquid.

If you hold all of these assets in your portfolio and you wake up ten years from now, you’re probably going to be disappointed at their value relative to how a stock and bond portfolio has grown over the past ten years. Central banks had lowered interest rates and did a number of other things to help boost their prices. That type of paradigm is largely over.

Financial assets are simply securitizations of cash flows. If those cash flows aren’t really there – a function of productivity and labor growth at the macro level, and revenue being above expenses at the micro level – then the asset values aren’t there either.

Because of all the debt and debt-like liabilities (e.g., pensions, healthcare, insurance, other unfunded obligations) in the US that are coming at us, we’ll need more returns but they won’t be there at the level needed. They’re currently at about 15x GDP so they’re never going to be paid through productivity outcomes.

Asset prices are currently at a level well beyond the economy through the liquidity that was pushed in by the central bank to be stimulative in a zero interest rate environment.

That’s pushed up the prices of all asset classes relative to their expected returns. Therefore, expected returns are going to be lower, especially relative to what kind of returns are needed. That’s just a reality that investors have to contend with.

And there’s also going to be low returns yet a lot of volatility around that. With less potent monetary policy, there’s the risk of having a downturn and not having the capacity to deal with that in the normal ways.

That makes sell-offs more violent. Then there’s the virus uncertainty about whether that’s coming back, which has the big economic implications about potential large drops in spending and income.

The new paradigm in monetary policy means there’s no longer the allocation of capital in the ways we’re used to it.

Before the way monetary policy would work was through the way the central banks would deposit cash. Then it was the bankers, and those who had the savings and capital, who would lend it out to people and institutions based on the perceived reward and risk of the investment.

Now it’s largely policymakers deciding who gets the money, who doesn’t, and how much. It’s a form of “state capitalism” rather than the previous form that was more hand’s off and “bottom up” rather than “top down”.

We cover more about US-China relations in a separate article and in a follow-on six-part series discussing the various types of “wars” or conflicts going on between the US (and to a lesser extent other Western democracies) and China.

This include conflicts regarding:

i) trade and economics

ii) capital and currency

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military armament

vi) internal conflicts within countries

Portfolio Construction

In previous articles, we talked about holding a well-diversified portfolio that can grow and capture risk premiums in most environments, and produce lower drawdowns, be less vulnerable to left-tail risk, among other benefits.

Diversifying well will increase your return per each unit of risk better than anything else you can practically do.

This is more important than ever before even if the returns of asset classes are not likely to be high, especially in real terms.

Most portfolios are structured to be long a specific asset class. Most investors are biased toward the stock markets of their own country.

Usually they have everything in stocks, or in stocks up to a level of volatility they can tolerate and sprinkle in some other assets (usually bonds) for the remainder.

The most important thing for most investors is to start with diversification of asset classes, of different countries and geographical regions, and of different currencies.

The one thing we know in this particular environment is that we don’t know much.

It’s not necessarily easy to time what’s going to happen. The markets are relatively efficient in making comparisons between the various choices of assets. It’s not always obvious to spot a mispricing and say that one thing is necessarily better than another.

The best thing is to diversify in a way that produces the excess return in a way that is as stable and the least risky as possible. The combination of different assets that do well in different environments will make it more stable.

Concentration in the traditional portfolio of stocks and in the same currency, as most tend to do, is dangerous, which is borne out historically. Everybody’s favorite asset class is going to decline some 50 to 90 percent during their lifetime.

In recent times, we’ve seen central banks come in to boost asset prices, replace lost incomes, and reflate the economy through “extreme” liquidity measures.

It’s likely they’re going to continue to do that where they can. Then it becomes a matter of how that manifests in asset classes. You can’t be sure exactly how it’s going to go.

– Does it drive up stocks in real or nominal terms?

– Does it drive down the value of money?

– Does it drive up gold prices that are priced as the inverse of money?

– What does it do to inflation?

– What is the role of inflation-indexed bonds (also known as inflation-linked bonds, or ILBs)?

From 1945 forward, with the institution of the Bretton Woods monetary system, that created a US and dollar type of world order. And through that, investors have learned certain habits and a way of operating.

It’s largely been great for US financial assets. But as the US has built up obligations and its role in the world declines (it gradually makes up for less of all economic growth), those types of returns are no longer realistic.

Nominal vs. Real Returns

The question of nominal versus real returns is important for certain types of investors.

Those concerned about nominal return targets are usually those with defined benefit plans, such as pension funds. They know exactly how much they’re going to have to pay out in the future and thus target nominal returns.

Those more concerned about real returns include endowments and foundations because they’re concerned about what they’re going to be able to purchase with these returns.

Risk for many types of investors pertains to an asset and liability mismatch. Some investors have a fixed return liability where the nature of their liabilities is known in advance. Others have a real return liability where the real purchasing power component is more important.

In engineering the portfolio when considering nominal versus real, the first consideration is what the base asset, sometimes called the “risk free” return, is.

For a nominal return portfolio, it’s a nominal return bond.

For a real return portfolio, it’s a real return bond, or an inflation-indexed bond (also known as an inflation-linked bond). For those more concerned about their real returns, then inflation-linked bonds become the base asset off which the portfolio is built from, as those pay the inflation rate.

Off that, the maturity of the base assets will need to match the nature of the liabilities.

In terms of going beyond that into other assets, it has to be consistent with the particular return objectives while being consistent with the liability stream. This ends up being an engineering exercise that is different from one market participant to another.

The overarching concern is that most investors – e.g., pension funds, endowments, foundations – relative to their liability stream, are not going to have enough income relative to their needs.

This is relevant to all companies and all individuals. They have a certain amount of revenue, they have a certain cost structure, and a certain amount of savings relative to liabilities.

Going through individual companies, you can see that some will not be able to pay out a certain amount of money based on the income they’re generating. That means they’re going to have to tap into their savings pool. Then it’s a matter of how long this can go on for.

Some companies can either raise capital to push out their time horizon or even receive direct government support if the costs to not “bailing them out” are higher than letting them fail. Some will default.

When it comes to retirement obligations, you can’t tell most people they won’t get their money. It’s not politically acceptable to default on those, so they’ll have to be monetized through further rounds of monetary “printing” to fill the liability gaps.

Other relevant factors to investing today

Beyond the constrained monetary policy landscape and fiscal policy determinations of what capital goes where, there are other elements that are very important to the markets today.

Importantly, we have various issues, like wealth gaps, opportunity gaps, values gaps, and political gaps that are driving more internal conflict. This is due to a variety of reasons.

One is monetary policy itself, which has aided those who held financial assets over those who didn’t, creating wider wealth disparities.

Another is the influence of locating production wherever it’s cheapest. Many parts of rural America have been hollowed out as the jobs that employed many people in certain areas have gone offshore. That’s led to depressed incomes and various types of issues like higher suicides, more opioid addictions, and so on. Then there’s the education issue, with certain groups having better access to quality education than others. That also has implication for adult incomes, incarceration rates, and so forth.

That’s driven more populist political tendencies and more of a wedge between the left and right. You have values gaps and this moves into what kind of leaders are elected, where you have a populism of the left (e.g., Bernie Sanders) and a populism of the right (e.g., Donald Trump).

When you have an economic downturn, all this boiling conflict that comes from these various issues tends to spill over in one way or another.

And who gets elected has implications for corporate tax rates, individual tax rates, capital gains tax rates, and other matters related to dividing up fiscal spending.

Geopolitics: US and China

There’s also the geopolitical landscape, particularly with the emergence of China to challenge the US as the dominant global power.

The current conflict between US and China is, in reality, a serious long-term geopolitical confrontation that will run on for decades going forward.

There’s the “trade agreement” stuff that seems to provide a détente, but is simply cosmetic and a small part of a bigger picture.

The heart of the situation is not just about balancing out trade flows or making those more even. China can buy more US products that it’s already incentivized to buy on some scale (like soybeans and natural gas).

But important structural issues that undermine China’s long-term strategic objectives are not going to be accomplished to too much of a degree.

This includes things like forced technology transfers for foreigners looking to do business in China, intellectual property theft, market access, market competition, government subsidies, cyber-espionage, and who controls what global spheres of influence.

We know that either the US will consolidate as the main global superpower, or China will rise in technological, economic, and military influence. If the latter, this will form a more bi-polar or multi-polar world and produce a bifurcation in the global economy that drifts away from a US-centered one.

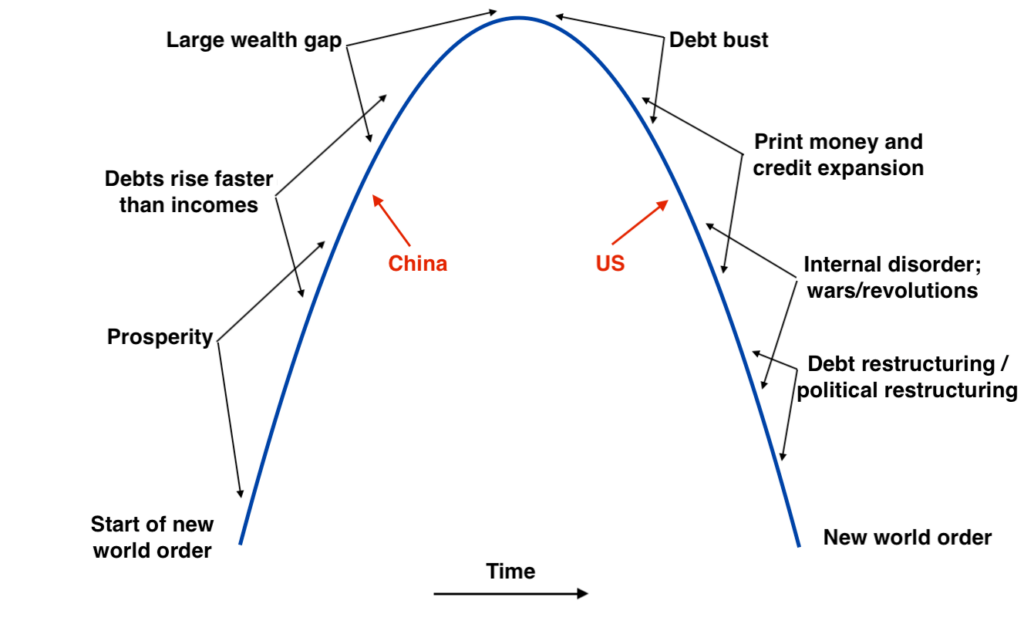

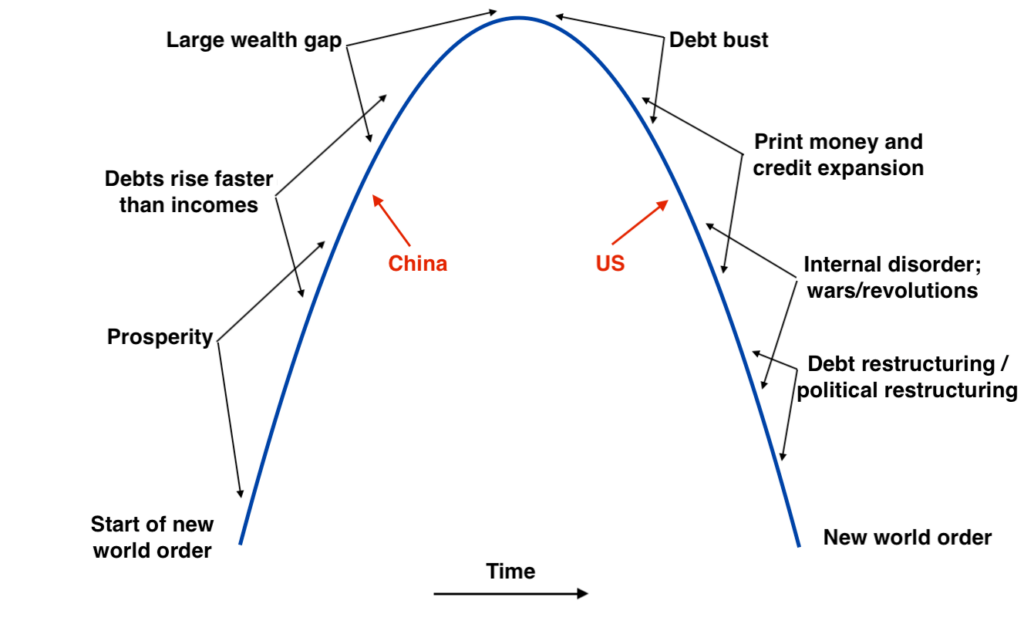

Roughly speaking, we could say that each in these particular respective stages of their current development arcs. For the US, their currency arc started in 1945 after the end of World War II that established the American world order. For China, it started with the Cultural Revolution in 1949.

There are different conflicts nested in one and going back throughout history, they all follow a certain template. There’s a combination of conflicts with respect to:

– trade

– technology and who produces what (together? independently with separate supply chains?)

– capital

– military and other geopolitical matters

With capital, one country may not want to own the currency of the other country through the bonds if the nation they have conflict with decides to unilaterally not make due on that amount. That’s been true historically and it’s true today.

Both economies could have separate supply chains. There could be competition and disparities over who develops what new, disruptive technologies (e.g., 5G, quantum computing, AI chips). There could be broader technological decoupling in other spheres.

This type of framework has occurred over and over again throughout history.

It’s a broader power struggle between a dominant power and ascendant power that’s happened over and over throughout history. The standard way these conflicts develop going back centuries is following the standard template – first it becomes trade, then economic and capital-related, then geopolitical in most other ways.

In the past 500 years where the ascendant power came up to try to supplant the dominant power there was a shooting war in 12 of the 16 occasions. In the other four cases, there were great pains taken to avoid one.

(Source: Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs)

In the 1930s, there was a downturn at the beginning of the decade, which set off various forms of internal and external conflict. There were “economic wars” and new alliances formed. Then came a real war at the end of the decade.

It’s not that a real war is necessarily the base case today. It depends on how the political relationships are managed.

China knows that this conflict is about the US looking to ensure its continued global geopolitical and economic dominance by poking at China’s weak points (i.e., their continued dependence on global trade, though that’s changing from a shift from a manufacturing-focused, export-centric model to an internal consumption-based model).

China has no incentive to agree to anything that structurally undermines its long-term strategic objectives. If they do, they won’t follow through.

This has big economic implications through the supply lines that can change in very permanent ways and have impacts on certain businesses. It can change capital movements. And it can also influence exchange rates.

This will be there for a long time irrespective of who’s in power in the US.

Multi-asset, multi-country, and multi-currency investing

In diversifying well, it’s important to be in different asset classes, multiple countries, in multiple currencies, and in reliable store-holds of wealth.

Wealth isn’t really destroyed so much as it shifts.

It shifts between asset classes, between countries, between currencies, and between different stores of value.

If you’re excessively concentrated in a certain thing you’re not going to be able to benefit when that wealth moves out in an environment inhospitable to that asset class (and/or the underlying country or currency).

If growth underperforms expectations, for example, that’s bad for equities. If you don’t have a portfolio that’s well-diversified to other asset classes and so on, you won’t have the assets to “catch” that movement.

With concentration, you’ll get some higher highs, but much lower lows, higher left-tail risk, longer underwater periods, and higher risk per unit of return.

If you’re only in stocks in your home country and home currency, you’re poorly diversified, as you’re only betting on a certain macroeconomic theme.

Sometimes it’ll work, sometimes it won’t and it will lead to very bad drawdowns.

As mentioned in previous sections, you’re dealing with lower-than-normal returns but the same or higher risks going forward.

If you balance well, you don’t necessarily have to predict shifts ahead of time or move around tactically. There’s always going to be competition between everything – i.e., one asset class to another, one country to another, one currency to another, financial to alternative non-fiat stores of wealth.

Capital and wealth is going to move around. Growth and inflation are the two big economic forces dictating this. Now we have the additional factor of zero interest rates no longer being a tailwind to financial assets or having the ability to offset drops in earnings.

So, the starting point is how to get to a risk-neutral strategic asset allocation and go from there.

When it comes to making tactical bets about what’s going to be good and bad, most investors should be very cautious about whether they can do that well. So, the risk-neutral “base portfolio” is a good bet to start with.

The most surprising things in investing

The things that tend to surprise you the most in markets are the things that haven’t happened recently or even in your own lifetime but have happened over and over again historically for the same logical cause and effect relationships.

Investors tend to extrapolate what they’ve gotten used to, but it’s always something different that’s going to get you.

For example, going over the past 20 or so years, the three major market crashes have all been very different in nature from each other.

In 2000, it was the collapse of the bubble in the tech sector.

Then it was a subprime debt crisis (mostly in the household and financial sector through housing). This was similar to the type of consumer debt bubble we had during the Great Depression. After that, the household sector and the financial sector deleveraged, but leverage increased in the non-financial corporate sector and at the sovereign level, only to see it all get derailed by a virus, of all things.

It’s important to know the mechanics of debt cycles. These are predominantly what drive movements in markets. Knowing what the central banks are doing is important, as they’re the ones with the biggest levers over liquidity, which is what drives markets.

Some important shifts tend to happen alongside the debt cycles, particularly the “breaking points” that cause big economic damage.

For example, big currency depreciations tend to happen alongside the end of debt cycles because devaluing your currency is one of the common ways to get out of it. It makes debt cheaper to service.

At the same time, understanding the nature of how things are now – and not just blindly following templates of the past – is important because each case is different.

For example, in 1933 and 1971 when there was the unlinking of currencies from gold it produced big moves in those currencies relative to the metal. Today, we’re much less likely to see those huge, abrupt depreciations because currency regimes are largely free-floating.

Political cycles also go around debt crises. Central banks pursue a lot of the same measures. These are necessary but the flows benefit certain groups a lot more than others. This leads to wealth inequality and so on, and drives calls for change.

Globalization helps efficiency in resource allocation and helps the whole. But the pain can be very real for many individuals. This contributes to opportunity gaps, income gaps, values gaps, and political gaps.

Certain periods in markets can go on for a while. But they often become overly extrapolated even when the underlying conditions change.

For instance, going into the financial crisis, we had short- and long-term interest rates above 5 percent in the US. That was a lot of stimulation capacity. That’s now gone.

What’s important for markets is what transpires relative to what’s discounted in.

Toward the end of cycles, you often see earnings growth extrapolated forward even when it’s not likely for various reasons. For example, with the pushback against globalization and the unlikelihood that corporate tax rates are going much lower, this means margins are likely toward secular highs.

If margins contract, that puts more pressure on sales to drive risk asset prices forward. But if economies are weighed down by a burden of debt and productivity growth (just 1.2 percent annualized over the past ten years) and labor market growth is lower, that also reduces the likelihood of above-trend growth.

Extrapolation of current conditions tends to happen but is often inappropriate.

From 2008 until 2019, for about eleven years, we were in a paradigm with the lowering of interest rates and quantitative easing. This decreased interest rates all along the curve. This increased risk asset values due to the present value effects.

You also had influences like share buybacks propping up stock prices. The interest rate on cash and other lending rates was low, which led to the buying back of their own shares. When interest rates get so low, it can be like a situation of automatically rolling over the debt and not having to go through with debt service.

It was a period that was very favorable to corporations, with low borrowing rates, margin expansion, individual tax cuts, corporate tax cuts, and so on.

Those things can’t be extrapolated indefinitely because there’s a limitation to how far that can be pushed.

You’re not going to get another round of tax cuts. You’re not going to get another round of a big cutting in interest rates. You won’t get the same level of share buybacks.

All of those tailwinds are gone. Investing in a zero interest rate environment is a challenge that all investors will have to grapple with.

Throughout history, the empires change, the personalities change, and the technologies change. But the same types of things occur over and over again for the same logical cause and effect reasons.

This period in the US and most of the developed world is analogous to the 1935-1940 period in various ways – with respect to monetary policy, fiscal policy operating within the context of polarized factions (more so than what’s typical), internal tensions (wealth gap, values gaps, political and ideological polarity), and external conflict with one power rising to challenge another.

Final thoughts

Developed markets are in a new monetary paradigm where the adjustment of short-term interest rates and quantitative easing no longer work. (This was already true for Japan and some developed European countries.)

This has pushed countries into a new joint fiscal and monetary policy approach of getting money and credit to where it needs to go.

We could have very large outcomes in the future path of the economy.

This could mean anywhere from additional deflationary outcomes that have been persistent over the past 40 years, to something like stagflation.

Or even paths like terrible growth and progressively higher inflation that throws policymakers for a loop. They’re so used to not getting inflation that the tendency has been to ease as much as possible.

Emerging markets are especially vulnerable.

Geopolitically, the world is going from a level of higher integration and interdependence to one that goes more toward self-sufficiency and less connected supply chains.

This could also provide traders and investors that diversify broadly to see lower correlation across global assets.

In this new monetary paradigm you can expect monetary policy and fiscal policy to be more extreme and expansive than normal.

The ultimate breaking point will come in terms of unacceptably high inflation and devaluation of the currency.

Potential currency issues may not be much of a theme in developed markets.

First, to replace the world’s top reserve currency (the US dollar) and the others (euro, yen, and a few more), there needs to be a better system first.

Second, currencies are largely floating rate systems, so large devaluations (especially relative to gold), like in 1933 and 1971, are unlikely.

It’s always important to have assets in your portfolio that can do well when stocks and other “big yield” assets perform poorly as an asset class. Over the past several decades, you could rely on safe nominal bonds to provide something of an offset. That’s now largely no longer the case.

But certain nominal bonds in emerging markets still have positive yields that could benefit if deflation is still the predominant global outcome.

In China, in particular, nominal bonds tend to do well when stock prices fall. This holds up the relationship that many in market participants in the developed markets have become accustomed to over the past several decades.

Emerging market bonds tend to be under-tapped by global investors. Access can sometimes be an issue.

Inflation-linked bonds, gold, and other precious metals are alternative stores of wealth and likely to be better than nominal bonds. Consumer staples, utilities, and other forms of defensive stocks that have stable earnings over time are likely to be more reliable.

Land is a classic inflation-hedge asset and is also a tangible and non-financial in nature.

But land and real estate also depends on its utility and what kind of income can be made from it. Malls, for example, have been in secular decline.

Student housing is generally viewed as a traditional hedge against recessions (when the economy is down, more people go back to school). However, more learning is done from a distance.

On the other hand, warehouses that act as e-commerce distribution centers near big population centers are on the way up.

Farmland and timberland tend to be less economically sensitive and sought after by some institutional investors for their diversification benefits.

The same could be said for types of assets like litigation loans that are not as popularly known.

Digital assets are a mixed bag. An online business providing steady income is clearly an asset.

On the flip side, digital currencies and cryptocurrencies are still mostly speculative assets that have governance and regulatory risks.

For most it’s not clear how they generate productivity to give them long-lasting value when they lack the main two features of a currency (a medium of exchange and a store of wealth). Most traders in this area are simply betting on the price movement.

Will governments allow to exist if they become material as an off-the-grid payments system? Even gold has been banned by governments throughout time for this reason.

Adding in some commodities as well could be useful.

Stocks that are likely to always retain their earnings, like consumer staples and other companies that sell products and services that are necessary to physically live, can take over more of a role from nominal bonds. They could serve as a type of bond alternative to replace the income lost from the now very low-yield fixed income securities.

Companies producing technological advances and are important for military or strategic reasons can also make sense in a portfolio.