Hyperinflation: Definition, Causes, Examples, Remedies

Hyperinflation refers to a situation in which goods and services inflation is very high and typically increasing in a non-linear way. It’s important for traders to understand the phenomenon because it can and will show up in some markets and can ruin entire investments.

During hyperinflation, the real value of the currency declines. People who earn their money in that currency are increasingly incentivized to convert their holding of said currency into more stable stores of wealth.

This includes more stable currencies, inflation-hedge assets like gold, and other real assets such as commodities, real estate, or even physical capital assets like tools and machinery.

In many types of economic contractions that turn inflationary – most recently Turkey and Argentina – policymakers are able to engineer a recovery where incomes and spending increase and inflation rates return to more normal levels.

With currency weakness, some economies are able to export more and import less and/or secure funding (from the IMF or elsewhere) that helps close these balance of payments gaps and equilibriums return.

However, some inflationary depressions spiral into hyperinflation where the prices of goods and services typically at least double every year. This accompanies extreme losses in wealth and severe economic hardship.

The fundamental cause of hyperinflation resides in the dynamic of the currency depreciation and the failure of policymakers to close the gap between external spending, external income, and debt service requirements. (An example involving early 1920s Weimar Republic will be covered later in this article.)

When the drop in the exchange rate leads to inflation, it can become self-enforcing and a dangerous feedback loop can develop that is rooted in investor behavior and the psychology of all economic participants.

With investors, each spurt of money printing is increasingly transferred to foreign or real assets instead of being spent on goods and services within the domestic economy to boost economic growth.

This behavior transfers from investors to all participants within the economy in order to hedge against inflation and preserve wealth. Foreign investors, unless they are compensated with an interest rate that offsets the combination of the depreciation in the currency and inflation rate, will not invest (once hyperinflation sets in, foreign investors bail completely).

Local currency bonds are wiped out and the price of domestic equities no longer keep pace with the drop in the exchange rate. The currency devaluation that took place pre-hyperinflation will no longer stimulate growth.

For workers, inflation spreads to wages. Workers demand higher wages to compensate for their loss in purchasing power. Producers, in turn, want to increase the prices of their goods and services to offset the rise in labor and other input costs.

This gets into a feedback loop that compounds on itself – currency depreciates, prices increase, policymakers print more money to cover the shortfall which also decreases the value of the currency, prices rise again, and so forth.

Key Takeaways – Hyperinflation

- Hyperinflation is most likely to occur in countries with no reserve currency, substantial foreign debt, depleted foreign exchange reserves, significant deficits, negative real interest rates, and a history of high inflation.

- In the face of economic and debt crises, central banks often struggle to maintain currency stability, leading to capital flight towards safer currencies and assets.

- This exacerbates inflation and hampers growth, especially in countries reliant on foreign capital inflows.

- The outcome of these crises largely depends on the efficacy of fiscal and monetary policies in managing debt levels and fostering economic recovery.

- During hyperinflation, safeguard investments by shorting the affected currency, transferring funds out of the country, and investing in commodities like metals and gold.

- Stocks eventually lag in a hyperinflation.

- When hyperinflation sets in, policymakers need to create a new currency backed by a hard reserve asset.

- Avoiding hyperinflation is a complex process.

- While halting money printing can theoretically prevent it, doing so can severely contract economic activity.

- This can lead to a vicious cycle of declining currency value and escalating prices, as witnessed in historical cases like the Weimar Republic.

- In Weimar Germany, external debt obligations and socio-political factors further fueled the crisis, illustrating the balance policymakers must maintain between fostering growth and preventing a sharp fall in economic activity.

- This is why governments often oscillate between fiat and commodity-based monetary systems to manage these challenges.

- Can hyperinflation happen in the US and other developed markets?

- The US’ status as a reserve currency holder and lack of high foreign debt make spiraling inflation unlikely, though its debt issues and the devaluation of debt and non-debt claims (e.g., pensions, insurance) is a long-term issue.

Background

Some think that when you create a lot of money this will directly feed into increases in prices in the real economy. While this can be true under the right mix of circumstances, one will find this erroneous when thinking on a transactions-based level.

It is the amount of spending that changes prices. This is true for anything whose equilibrium price is determined in a market where its price is a function of the total amount spent divided by the quantity.

During the financial crisis in 2008, there was a large drop in credit creation. The central bank dropped interest rates, bought financial assets, and the fiscal government helped by providing credit guarantees and direct payments to help support economic activity.

If the amount of money is offsetting a drop in the amount of credit, then prices won’t change. They are simply negating each other when the amount of money is brought up to replace the shortfall in credit.

If the amount of credit is contracting and the amount of money is not increased to counteract this shortfall, the total amount of spending will fall and prices will decline.

Where is hyperinflation most likely to occur?

Depressions that are inflationary in nature are possible in all countries and currencies, but they are more likely to occur in countries with the following mix of conditions:

- Do not have a reserve currency

- Large foreign debt

- Low foreign exchange reserves

- Large deficits (i.e., a large fiscal deficit and/or current account deficit)

- Negative interest rates in inflation-adjusted terms

- A history of high inflation

A more complete explanation of these factors

When a country doesn’t have a reserve currency, it means there is no global preference to hold their currency, debt, or financial assets as a means of holding wealth.

When there is a large foreign debt stock, the country becomes vulnerable to the cost of the debt rising either through an increase in interest rates or the value of that currency going up.

With low FX reserves, a country may lack adequate buffer room to protect against capital outflows. If capital outflows exceed the extent of their FX reserves, a country can lose control of its currency (i.e., little ability to arrest a depreciation).

When there are fiscal or balance of payments deficits, then the government will need to borrow or create money to fund it.

Interest rates that are below inflation rates – i.e., negative real interest rates – means that lenders won’t be adequately compensated for holding the currency or debt. When central banks lack adequate FX reserves, they cannot buy their currency on the open market to support it.

Their next step is to offer an interest rate that offsets both the depreciation in the currency and the inflation rate to compensate lenders and holders of the currency.

For traders, that is the means by which you can identify the bottoms in the currencies undergoing these types of inflationary crises (most recently Turkey and Argentina in 2018).

When a country has had a history of going through these types of issues and there have been negative returns in the currency over time, it is more likely that there will be a lack of confidence in the value of the currency and debt.

For example, people in the US put a lot of trust in their currency. Most US-based investors do not diversify much by currency. They tend to own a lot of stocks and bonds denominated in their own currency; even most emerging market investments are translated back into USD. This is the natural bias.

Those in emerging markets – and particularly those in countries where there’s been a history of debt and currency problems (e.g., Argentina, Turkey, Russia) – tend to place less faith in their currencies and many choose to diversify by owning foreign assets and/or alternative stores of wealth like gold.

Can these occur in more stable countries?

The more a country fits the above profile across those six main criteria, the more likely a depression is to be inflationary. The most popular case in modern history is the hyperinflation that occurred in Germany’s Weimar Republic in the early 1920s. This case is covered in more detail in the latter part of this article as a mini case study.

Reserve currency countries that don’t have material amounts of foreign currency debts can have depressions that are inflationary in nature. However, to the extent that they do, they don’t to be much less severe and are likely to occur later in the process. I

f inflationary pressure does emerge, it is likely to occur due to overuse of stimulation to offset the deflationary depression that is characteristic of the type reserve currency countries go through.

When a country experiences capital outflows, this is negative for demand for its currency, causing pressure to depreciate. When a currency depreciates, the trade-off between inflation and growth becomes more acute. This is true for a currency regardless of the global bias to hold it as a reserve.

If the central bank of a reserve currency country allows for higher inflation to keep growth stronger (i.e., not hiking interest rates to encourage credit growth) by creating currency and keeping monetary policy easy, it can undermine demand for its currency. This can make investors view it as of lesser quality and weaken its status as a store of wealth.

The typical dynamic in reserve currency countries without foreign exchange debt is one where contracting credit is offset by money creation. But creating currency can be overused at a point that could lead to inflation. However, unlike in non-reserve currency countries, inflation is typically easy to negate because all the central bank has to do is stop feeding the stimulant (money printing) or raise interest rates even slightly.

This is particularly true for an indebted economy. Countries that recently went through a debt crisis usually still have ample amounts of debt relative to income. This means any tapping of the brakes on monetary policy tends to be very effective.

What caused hyperinflation in Germany?

Entire books have been written about the German Weimar Republic hyperinflation that reached its crescendo in 1923. In the interest of brevity, given the purpose of this article is to give an overview of the mechanics of how and why hyperinflation occurs, we will give a broad synopsis.

Weimar Germany’s hyperinflation was borne out of the war reparations requirements stemming from its loss in World War I. It also illustrates that the single biggest mistake a world leader can make is starting a war, losing it, and being saddled with crushing reparations debt.

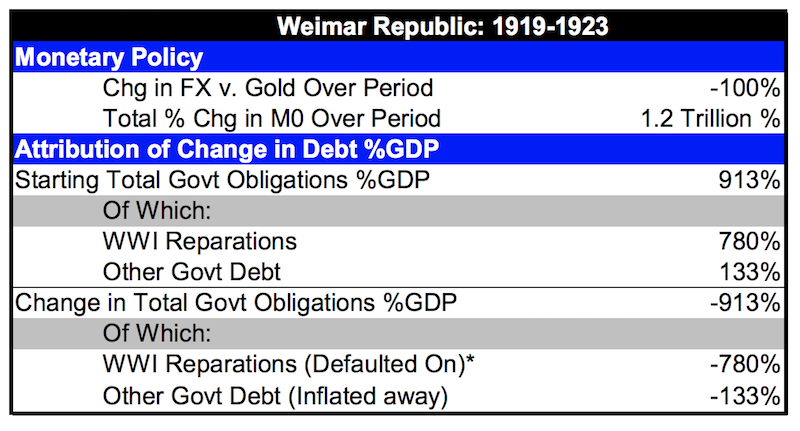

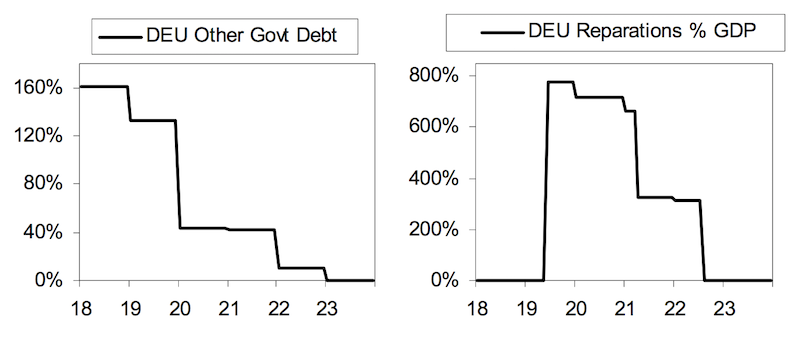

In 1918, after the war ended, the government had a debt to GDP ratio of roughly 160 percent after their borrowing binge to finance war spending. However, after the Allied parties imposed reparations obligations on Germany, to be paid in gold, the total debt and obligations rose to 913 percent of GDP (780 percent of that attributed to war reparations).

It was known by the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 that reparations payments would be massive. The exact amount that would be required wasn’t set until the start of 1921. This came to 269 billion gold marks and had to be restructured given the burden relative to national income.

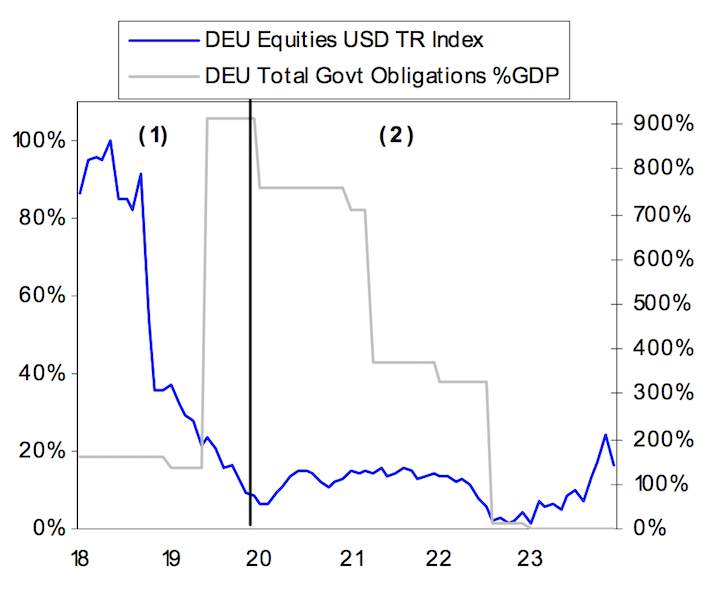

The chart below shows the Weimar Republic’s debt obligations relative to the value of its equities market.

(Source: Global financial data)

In 1918 and 1919, toward the latter stages of the war and directly after, German incomes (in real terms) fell 5 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

In response, the Reich helped encourage a recovery in incomes and asset prices by devaluing the paper mark against the dollar and gold by 50 percent between late 1919 and early 1920.

As the paper mark fell, inflation rose, as its apt to do, part of it being attributed to more expensive imports and increased demand for exports.

From 1920 to 1922, inflation eroded the value of government debt denominated in marks. However, it made no difference on the reparations-related debt given. It was purposely designed to be owed in gold so it could not be inflated away.

In the spring of 1921, the Allied Reparations Commissions restructured the reparations debt to half its original value to 132 billion marks. This was still a heavy burden to the government at 325 percent of GDP.

By mid-1922, the Reich decided to stop making reparations payments, effectively defaulting on the debt.

After this point, the debts were restructured several times via negotiations – to 112 billion in 1929 and then effectively wiped out by 1932. The level of currency depreciations caused creditors (i.e., those being owed the money) to favor short-term loans and move money out of the mark currency.

This led to further depreciation of the mark, and required its central bank to keep printing to buy the debt and prevent the economy from becoming illiquid (i.e., not enough currency relative to the demand for it).

This dynamic of capital outflows (currency being converted into other national currencies and alternative currencies like gold) with the void being filled by printed money to buy the debt led to the ultimate hyperinflation in 1923. This process accelerated in 1922 and 1923. It ultimately left local currency government debt at 0.1 percent of GDP.

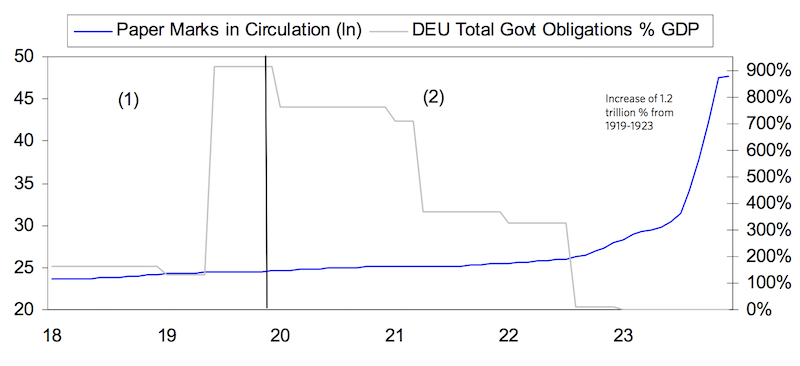

By the time the hyperinflation ended in 1923, the Reichsbank had increased the M0 money supply (i.e., cash and reserves) by 1.2 trillion percent between 1919 and 1923.

This left the Weimar Republic as one of the most extreme inflationary depressions in modern history.

At the end of the war, the Reich government had to choose among severe economic contraction or printing money to stimulate incomes and asset prices and risk the currency and severe inflation down the road.

This set of trade-offs was unpalatable, but the government inevitably chose to print, which is the natural desire to keep the economy and incomes afloat. Its 50 percent devaluation at the end of 1919 did enough to bring the economy out of recession.

But the extreme stimulus measures led to an eventual loss of confidence in the currency and hyperinflation. The end result was a currency that was virtually worthless, both as a unit of account (a massive line of zeros) and for commerce.

The chart below shows that the currency fell 100 percent against gold and the exponential nature of the money printing, increasing the money supply by 120 trillion times (1.2 trillion percent). Its non-reparations government debt of 133 percent of GDP was wiped out by inflation. The reparations debt tied to gold of 780 percent of GDP went into default in the summer of 1922 and reparations payments were halted.

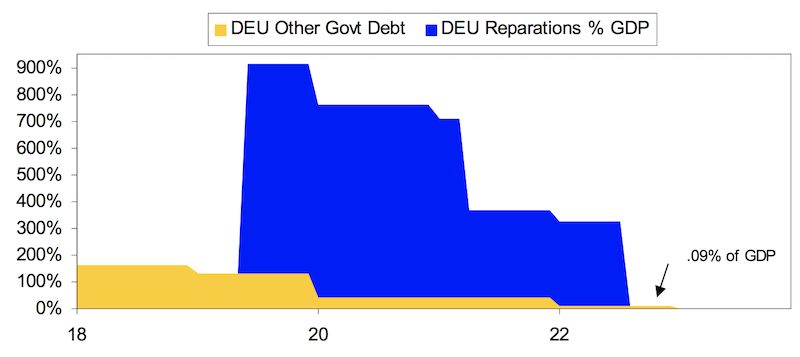

Below shows debt obligations and their magnitudes as a percent of GDP, divided between reparations and government debt and their changes from 1918 to the end of the hyperinflation in 1923.

Reparations were not officially imposed until 1921, though they notionally existed from just after the completion of the war. It was just a matter of how much the Reich government’s total bill would be. This amount was officially settled at the beginning of 1921. It was later reduced, pre-hyperinflation, to 50 percent of the original burden, though still a massive sum.

The local currency government debt was eroded through inflation. But because the reparations payments were denominated in gold, they held their value until the Reich effectively defaulted on them

The increase in M0 (currency and reserves) was not the cause of the inflation and currency depreciation. Rather the money supply was increased to help accommodate the higher inflation and currency depreciation.

This formed a self-reinforcing inflationary cycle. The increased need for money was accommodated by the central bank creating more of it.

This led to currency weakness, higher inflation, and less capital flowing into credit. This created more demand for money to keep up with rising prices, which the central bank accommodated.

General Points

1) Debt is one entity’s asset and another’s liability

2) Debt is a promise to provide currency (i.e., money) in the future in a particular currency (e.g., USD, EUR, JPY, GBP, etc.)

3) Currency and debt serve two basic purposes: i) a means of exchange and ii) a store of wealth

4) Those who own debt expect that such assets will provide the opportunity for them to receive money down the line. In turn, they plan to eventually convert these assets into goods and services (or other financial assets). As a consequence, holders of these assets are very mindful of the rate at which its purchasing power is lost (i.e., the rate of inflation) relative to the compensation provided (i.e., the interest rate on the debt or currency) for holding it.

5) Central banks and other monetary authorities can only create money and credit that is within their control. The US Federal Reserve can only create US dollar-denominated money and credit, the ECB can only create euro-denominated money and credit, and so on.

6) Central banks and borrowers – the fiscal side of the central government and private sector entities through its member banks – usually create larger amounts of debt assets and debt liabilities. It’s easy to create debt and financial assets, but over the long-term not a lot of thought is put into how these liabilities are going to be paid for.

Financial assets, in the end, are securitizations of cash flows. If these cash flows don’t exist, or at least not up to par relative to the value of the asset, then what owners of these assets believe are “assets” aren’t actually so, either worth a fraction of their face value or nothing at all.

7) The greater the debt burden, the more difficult it is for central banks to get policy right (both inflation relative to output and incomes relative to debt servicing), such that the economy doesn’t fall over into either a deflationary depression or inflationary depression, depending on the mix of circumstances in the country that makes it susceptible to one or the other.

8) Central banks generally want to relieve debt crises by creating money in which the debt is denominated. Usually this works in reserve currency countries where the clear majority of the debt is denominated in domestic currency. They can change the interest rates and change the maturities to spread out the obligations and print money to offset any funding shortfall.

Countries without reserve currencies often borrow in foreign currencies, making money creation to relieve debt less viable because of how it changes the relative exchange rates. Monetary policymakers also want to spend on financial assets to help reduce burdens further and lower borrowing rates. This lessens the value of the currency, holding all else equal.

9) Fiscal and monetary policymakers can usually balance out deflationary forces (e.g., debt contraction, austerity) with inflationary forces (e.g., money printing). Debt burdens can be restructured so they are spread out over time. They not always get the balance right.

10) Particularly relevant for emerging countries where inflationary depressions commonly occur: If a currency declines in relation to another currency at a rate greater than the interest rate being offered on the currency, the holder of the currency and debt denominated in it will lose money.

If investors believe that this weakness will continue without being compensated with a higher rate of interest, the currency will continue to fall. Moreover, the currency’s fall and subsequent impact on inflation will become increasingly magnified if not interrupted.

The currency dynamic is the key component of hyperinflation

The currency dynamic is what causes depressions to be inflationary in nature. Those who hold currency and debt denominated in the falling currency will want to sell it and move into a different currency or alternative store of wealth such as precious metals.

When there is the dual combination of a weak economy and a debt crisis, it often becomes impossible for a central bank to raise interest rates enough to offset the currency weakness and get the currency to bottom.

Accordingly, money leaves the currency for safer currencies and alternative ways to store wealth. When money leaves the country, lending increasingly declines and the economy slows down. The central bank is either faced with the choice between letting credit markets dry up or creating money, generally ample amounts to offset the contraction in credit.

It is broadly known among economists, traders, and other market participants that central banks face a trade-off between output and inflation when they change interest rates and liquidity in the financial system.

What is not as commonly known is that the trade-off between output and inflation becomes much more acute when money is leaving the country. Likewise, it becomes easier to manage when money is flowing into a country.

This is because these positive capital inflows can be used to increase foreign exchange reserves, lower interest rates, and/or appreciate the currency, depending on how the central bank chooses to use this advantage.

Demand for a country’s currency and debt will increase their prices, holding supply constant. This, in turn, will lower inflation and increase growth if the amount of money and credit are held constant. When there is less demand for a country’s currency or debt, the reverse process will occur where inflation is pushed up and growth is pushed down.

When a country has a reserve currency, they derive an income effect from it, as they can borrow more cheaply.

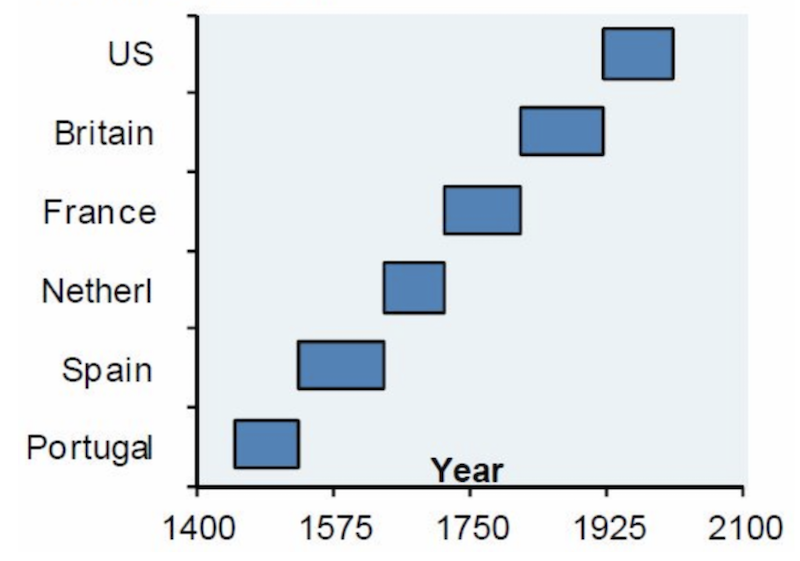

Having a reserve currency, overborrowing in it because of the income advantage, and having fiscal and current account deficits rise to levels that endanger the status of the reserve currency is a classic phenomenon that occurs throughout history.

The change in demand for a country’s currency and debt will have an influence on interest rates. The degree to which this happens depends on how the central bank uses its policy tools. When money is moving out of a currency, real interest rates need to increase less if real exchange rates decrease more.

Capital moves out of a country when debt, economic, social and/or political problems occur. This generally hits the currency, sometimes substantially.

Those who borrow in a stronger currency (usually because its interest rates are lower, as they tend to be lower in the top reserve currencies) and use it to fund business activity that generates them incomes in domestic currency usually see their borrowing costs go higher.

This makes economic activity in the weaker currency country even less viable, so the currency takes a further tumble relative to the stronger currency.

Because of this, countries with the combination of high indebtedness, high amounts of debt denominated in one or more foreign currencies, and a large dependence on foreign capital inflows generally have substantial currency weakness.

This generally comes to a head when there’s an event that triggers a downturn in economic activity. The currency weakness is what causes inflation to occur when the downturn comes.

Normally an inflationary contraction ends when the currency and debt prices decrease to the point where they are very cheap and net capital inflows resume. One or more of the three factors is generally true:

- i) The debt service requirements are reduced, such as debt forbearance

- ii) The debts are defaulted on or enough money is created to help support debt payments

- iii) The currency depreciates to a larger extent than inflation increases, such that the country’s assets and exports become competitively priced and its balance of payments situation improves

How fiscal and monetary policymakers handle the situation matters. Contractions of both the deflationary and inflationary varieties are self-correcting mechanisms. At the most basic level, debt is too high relative to income.

This eventually must be corrected because it can’t continue indefinitely. Political decisions can either help or hurt the progression of the process. Namely, are policymakers capable and do they have the authority to make the best decisions possible?

How to invest during a hyperinflation

What to do during a hyperinflation? Most traders have never experienced a hyperinflation personally or been in the markets of a country undergoing this process.

Whether you’re an investor (hopefully looking from the outside in) or a citizen, the playbook of investing during a hyperinflation period has a few tenets to go by:

- Short the currency

- Get your money out of the country (i.e., don’t own the currency and don’t own the bonds)

- Buy commodities and commodity industries, such as metals and gold

What about stocks?

Some view stocks as a way to protect yourself against inflation as a general piece of advice.

However, in a hyperinflation world, it’s a different story.

While the stock market may be a good place under normal inflation circumstances, the transition between inflation and hyperinflation makes equities an increasingly bad place to store your wealth.

Normally there is a high correlation between the prices of shares and the exchange rate.

If you’re a US-based investor in USD denominated equities, for instance, you don’t care much about the day to day oscillations in the price of the US dollar. In general, if your domestic currency goes up or down much, you typically don’t have much reason to care if your stocks are denominated in local currency.

In times of hyperinflation, there’s a divergence between share prices and the exchange rate.

Even though shares continue to rise in local currency terms, they begin to lag and lose money in real terms.

Gold becomes the asset of choice, stocks become a terrible investment, and bonds are zeroed.

In general, people want to buy any asset that’s of a “real” or non-financial character. This includes land, machinery, factories, tools, metals, and natural compounds.

Even finished goods and capital investments like construction equipment will get purchased as stores of wealth even though they’re not needed for their originally manufactured or intended purposes. In the Weimar Republic, even granite, sandstone, and various forms of minerals became desired things to own.

Once inflation reaches “escape velocity” – i.e., policymakers can’t close the imbalance between external income, external spending, and debt servicing requirements, and keep printing money to make up the gap – it spirals into hyperinflation.

At this point, the currency will never recover its status as a way to store wealth.

What do governments need to do once hyperinflation takes control?

They need to create a new currency backed by a hard reserve asset.

This needs to be something that is not subject to large swings in demand. Throughout history, this has typically meant gold and to a lesser extent silver.

So, a government will typically create a currency backed by gold, though it could theoretically be backed by something else (such as an oil-rich country backing it with its oil reserves).

Whatever is used, the government must create a new currency with a hard backing at the same time they discontinue use of the old currency.

Is hyperinflation avoidable? Can hyperinflation be reversed?

Some believe that hyperinflation is avoidable if policymakers just stop printing money. However, it is not easy to simply stop creating money.

If policymakers stop printing money when capital is flowing out of the country it causes a steep drop in liquidity and usually a very deep fall in economic activity. The longer this occurs, the harder it becomes to stop.

In the Weimar Republic example, cash kept leaving the country because it was so detrimental to keep holding it in local currency. Once the inevitable kicked in, it kept losing value literally by the second.

That meant the existing stock of money in circulation became insufficient to buy goods and services. By October 1923, Germany’s entire stock of money from ten years prior would have literally bought you only a fraction of a loaf of bread.

If they had stopped printing, that would cause economic activity to dry up completely. One of the two uses of a currency is its use as a medium of exchange (the other a store of wealth).

If there is no currency available, then economic activity can’t occur in the normal ways. So printing seems like the best choice even if it does feed the inflationary spiral of which there is no way to get out of.

On top of that, money often breaks down as a means of exchange entirely. As a unit of account, with a long line of zeroes behind it, it becomes useless.

The lack of stability in the currency makes producers and merchants unwilling to sell their goods and services for local currency. Accordingly, producers will often demand payment in foreign currencies or else barter for other goods and services that they need.

In Weimar Germany, US dollars became a source of exchange, but there were far too few that came into circulation. And because of the currency’s value – and virtually any external currencies were much more valuable given the ongoing by-the-second devaluation – it became hoarded.

At a large enough scale, the lack of willingness for producers to accept domestic currency creates illiquidity in the economy. This causes demand to collapse.

Further money printing can’t resolve the situation because confidence in the currency is lost. Accordingly, stores close and businesses cut their employees.

Hyperinflation goes hand in hand with a rapidly contracting economy. The very high and/or accelerating currency declines zap trust and sow chaos.

Not only is there economic contraction, but financial assets cannot keep pace with the combination of the inflation and rapidly falling currency. Accordingly, hyperinflation wipes out financial wealth.

Debtors who owed money in domestic currency see their liabilities inflated away and lenders see their wealth evaporate. People at every level of the economic strata are badly worse off. Social and political conflicts intensify. Internal strife becomes rampant.

Many people, particularly those in the public sector, also refuse to work because they don’t want to work for money that is worthless. This means police officers and other public servants often stop their service.

Looting, crime, violence, and general anarchy break out. Weimar Germany dealt with such matters by having the military stamp out the unrest and rioting. The military would also take up the duty of carrying out arrests.

In the case of the Weimar Republic, its printing was not something it could stop. Its war reparations requirements meant that its external debt servicing would be very high for a very long time. There was no way for them to conceivably default, though they eventually did in 1932.

That brings up the question: Why did creditors insist on punishing Germany so harshly despite the clear humanitarian crisis it would cause?

Creditors were worried about allowing a way for the country to default lest it result in the revival of German militarism, which did occur after the reparations default in 1932.

Hitler came to power in March 1933 at the same time the rest of the developed world was struggling with their own economic depression, which fueled populist political movements.

When economic conditions are very bad, this creates various forms of social discord and spills into political movements. People increasingly look toward strong, charismatic figures to take control of the situation.

The sheer amount of capital (paid in full and in non-depreciated currency given the linkage to gold) that would need to be paid by the Reich government by the end of World War I – and thus flow out of the country to pay these creditors – all but guaranteed that Germany would face massive inflation problems.

Outside of Weimar Germany’s case, policymakers often opt to keep creating money to cover external spending because they want to keep growth up. Long-term, spending needs to be kept in line with income, which in turn needs to stay in line with productivity.

If printing is done over a long period of time and on a large scale, a country might face hyperinflation even if it could have been avoided by closing the gap between spending and income and debt servicing requirements, even if it means a big economic contraction at the outset.

But it’s a tough decision to make.

In the worst circumstances, all economic activity can grind to a halt if printing money is ceased – at least until they come up with a different currency with a hard backing. This is also why historically governments have tended to oscillate between fiat monetary systems and commodity-based monetary systems.

Commodity-based systems are prized for the discipline in money and credit creation that they impose.

But when economic problems become onerous enough, policymakers either change the conversion between the currency and the commodity that backs the currency (i.e., usually gold) to get more money and credit into the system, or they abandon the system altogether in favor of a fiat monetary system.

Under a fiat system, debt problems generally become burdensome to the point where policymakers need to deprecate the currency by creating more of it, sometimes to a point where it endangers the currency as a useful asset.

Reserve currency status doesn’t last.

Even though these inflection points in currency regimes occur infrequently, they do happen and are always underestimated because they rarely occur during our lifetimes.

Investment assets as stores of value

Higher-than-normal inflation is not something that most traders and investors have come across in their lifetimes.

So, it’s important to look through history to understand more about how to trade well through that type of environment.

Investors always need to keep in mind that what they put their money into should fundamentally be a quality store of wealth.

We think this will be an important consideration going forward, as key tailwinds for financial asset markets (e.g., lowering short-term and long-term interest rates, tax cuts, globalization’s impact on margin expansion) are no longer there.

This is especially true in developed markets going forward where cash rates are around zero (or negative in some cases), bond rates are around zero or even negative yielding. The yields on stocks get pushed down toward those levels as well as more money and credit gets pushed out over the risk curve.

Cash and bonds

Quality stores of wealth can take a variety of different forms. Traditionally they can be cash or bonds. But when those don’t yield anything in nominal terms and yield negatively in real terms, they aren’t the best investments and are practically useless for income generation purposes.

It calls for a different portfolio strategy.

Being long some nominal bonds in geographies where interest rates are still materially positive can be viable, whether that’s through buying the bonds themselves or through proxy vehicles like ETFs.

If deflation wins out, which is entirely possible given the deflationary forces are so large, those are likely to increase in value. And they have positive spreads to begin with and can offer some level of currency diversification.

Inflation-linked bonds (commonly abbreviated ILBs) are also something for investors to consider.

Instruments like Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) and inflation-linked gilts (ILGs) provide a base yield plus inflation (usually defined as CPI or the official government-defined metric). They effectively act as an inflation-hedge asset. They can provide another source of diversification.

Stocks

Some stocks can be quality stores of wealth, such as those who provide basic “staple” goods (e.g., food, basic medicine) that will always be in demand anywhere as they are necessary to physically live.

The stocks of certain technology companies that are on the frontier of productivity can also be quality stores of wealth.

Gold

Gold can be a quality investment as a cash alternative. Central banks want wealth store-holds and investors are interested in currency hedges when real interest rates become unacceptably low.

Gold is simply a contra-currency. It’s effectively the inverse of money, priced in dollars per troy ounce, euros per troy ounce, or whatever the reference currency.

Though gold is at a strong price point in most currencies, the dynamic isn’t really that “gold is going up” or it’s utility has gotten higher, it’s that the value of money has declined. It’s a natural consequence of real interest rates falling and the ongoing need to print a lot of money to meet debt and increasingly debt-like obligations (e.g., related to pensions, healthcare, insurance, and other unfunded claims).

Gold’s long-run value is proportional to currency and reserves in circulation relative to its supply globally. It functions closer to a currency than a commodity subject to traditional supply and demand for the physical good.

It acts as a reference point for the value of money, which is a question that will gain in importance over time.

Real estate, land, and tangible assets

Real estate and land can be quality stores of wealth but ultimately rely on how they’re used, which impacts their values and can change over time.

If, for example, we considered the value of malls and e-commerce distribution centers decades ago relative to today, they’d be very different in relative value terms.

Land and real estate investing is still one of the oldest forms out there and can play a part in the construction of any portfolio.

Digital currencies and cryptocurrencies

Newer asset forms like digital currencies and the cryptocurrency sub-category could eventually play a role, but are currently nascent in their development.

The vast bulk of cryptocurrency activity is tied to speculation and not toward legitimate value creation purposes (e.g., modernize payments infrastructure where our current payments systems are slow and cross-border transactions are inefficient).

Going forward, certain digital assets have the potential to expedite intermediary functions (e.g., do away with the duplicate information kept by various banks in many forms of transactions), reduce costs, streamline operational processes, and so on.

But they’re a very long way from being sound, dependable payments networks that can scale up to broader adoption in financial and non-financial contexts. Governance is a major problem so it doesn’t make much sense to rapidly integrate cryptocurrency technologies (e.g., “permissioned blockchain”) until that’s better worked out legally and in various regulatory spheres. For instance, it doesn’t take much for miners and validators in a specific network to collude to affect its integrity.

And they have an extremely long way to go before being considered a source of reserves by central monetary authorities or as currency hedges by large institutional investors.

Further reading

A more in-depth discussion on stores of wealth was covered in a separate article: The Future of Trading & Investing: A ‘Store of Wealth’ Perspective

In regards to the prospect of inflation in the developed world and, generally, how to traverse a larger-than-normal subset of unknowns in building a portfolio, we also covered those matters in the following article: Stagflation: How It Occurs And Building a ‘Stagflation Portfolio

Can hyperinflation happen in the US or developed markets?

The US has three of the six aforementioned characteristics:

- low FX reserves

- large funding deficits

- negative real interest rates

But it doesn’t have the others:

- The US does not have a history of high inflation (it’s been more episodic)

- It does not have high foreign debt

- And the USD is a reserve currency

The US has the world’s top reserve currency but lacks FX reserves/”world money”. The US’s financial situation is not sustainable, but is not likely to lead to spiraling inflation because it lacks foreign-denominated debt commitments as is typical.

However, the US will eventually face a large debt reckoning. And it will essentially devalue its way out of this given the lack of other options that are politically palatable – e.g., higher taxes (impossible to get the money needed because the productivity growth rates are too low), lower spending, lower incomes.

When the loss of reserve status occurs, it means Americans will no longer get to spend as much as the decline in the currency will go on until a new balance of payments equilibrium is reached.

In other words, this means there will be enough forced selling of real and financial assets and enough curtailed buying of them by US entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

This works as a self-correcting process in order to rectify the excessive borrow-and-spend pattern that produced exceptionally large liabilities and debt obligations relative to income.

Debts cannot rise above incomes, and incomes cannot rise above productivity forever.

The social and political impacts of the US eventually paying the price for its excessive spending will be horrible.

It will mean that Americans can no longer spend as much because the US can no longer use its reserve status to borrow large amounts of money to fund these expenditures.

Final Thoughts

Hyperinflation is the state where economic inflation is very high and typically accelerating.

Hyperinflation is typically seen in the economic depressions of countries that have the following mix of characteristics:

- lack of a reserve currency

- high foreign-denominated debt

- low FX reserves

- large fiscal and/or current account deficits

- negative real interest rates, and

- a history of inflation or negative returns in the domestic currency that undermines trust in it.

Typically, when countries that borrow a lot in a foreign currency undergo an economic shock, their currency declines, which makes their debts harder to service because so much of it is denominated in a foreign currency.

That incentivizes them to print money to cover the shortfall, which causes inflation, more printing to cover the debt, and so on, until a dangerous spiral emerges.

For example, if the currency you earn your income in declines 50 percent relative to the currency you pay your liabilities in, that’s effectively like a doubling of your debt servicing obligations.

When the debt burden is too much and the country lacks foreign exchange reserves, they have to print money to service it if they have that ability. The extra money being created depreciates the currency further.

That incentivizes residents and investors to get out of the currency fearing that the currency and assets held in it will be of depreciated value.

If the central bank doesn’t deliver an interest rate that helps compensate for the rate of depreciation and the rate of inflation, a dangerous dynamic develops that fuels a further drop in the currency.

It is the currency dynamic that fuels the inflationary nature of the depression.

Reserve currency countries can have inflationary depressions as well, but if it does, it usually comes later on in the process after the overuse of monetary stimulant.