Reserve Currencies: A Fundamental Overview of Where Each Stands

Reserve currencies are foreign currencies, precious metals, or other reserve assets that are held by countries’ governments, central banks, or central monetary authorities to hold as part of their foreign exchange reserves.

Reserve currencies are used to save in, transact in, stabilize one’s own currency, or use for investments. They are often called safe-haven currencies.

Every dominant empire throughout time has had a reserve currency. As dominant powers develop, their trade and capital flows are positive. Others want to invest in the country and have the goods, services, and assets it offers to the world.

Trade routes require a strong military. This also helps influence others outside of their own main territory.

Having a large share of global trade helps develop the usage and desire for its currency. The money gets passed around and more people want to use it.

A pervasively used currency as a medium of exchange and store of value, in turn, helps develop its debt and equity markets.

Developed financial markets help develop a leading financial center in the world for both attracting and allocating capital.

This was Amsterdam in the Dutch empire, London in the British empire, New York in the American empire, and now Shanghai (and to a lesser extent Shenzen) is being developed during China’s ascent.

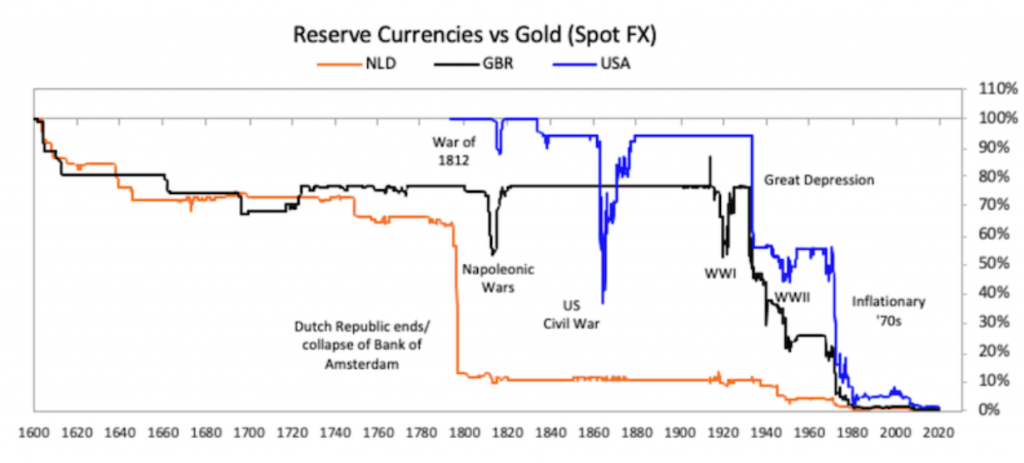

In the mid-1600s, until the collapse of the Bank of Amsterdam in the late-1700s, the Dutch guilder was the world’s leading reserve currency.

From the late-1700s to the first half of the 1900s it was the British pound.

After World War II and the establishment of the Bretton Woods monetary system, the US was clearly established as the top global player economically and militarily. The dollar became the world’s top reserve currency.

Right now, global reserves – i.e., the share of central bank reserves by currency – are around the following percentages:

– USD: 53%

– EUR: 20%

– Gold: 14%

– JPY: 6%

– GBP: 5%

– CNY: 2%

Their relative weightings are from a combination of:

a) the fundamentals that influence their relative appeals and

b) the historical reasons behind why they’re used

The USD now accounts for about only 20 percent of global economic activity but is more than 50 percent of global reserves, and around 60 percent if excluding gold. This is because of the US’s reputation and less so because of its fundamentals.

The same was true of the Dutch guilder and British pound, which maintained popularity even after the relative declines of their respective economic production and military power.

Why reserve status runs with a lag relative to the decline of an empire

Reserve status lags an empire’s fundamental reasons by decades because it’s not easy to change the system.

This is somewhat analogous to languages. Back in the late-1400s through the 1600s the Spanish empire was strong. Through their territorial expansion, the Spanish language spread through South America, Latin America, and into parts of North America.

The world’s top four reserve currencies – USD, EUR, JPY, and GBP – are what they are because they represented the leading empires in the post-World War II period. However, on a fundamental level, they are weak relative to their current standing.

The levels of each currency as a function of global reserves are too high relative to what amounts you’d want to have in order to be balanced – e.g., relative to economic activity, trade activity, relative growth levels – and where the world is going.

The European currency, yen, pound, and increasingly the dollar are in widespread use because of archaic reasons.

These currencies came out of the 1970s era Group of Five (G5) that represented the top five countries by GDP per capita – the United States, West Germany, France, Japan, and the UK.

Below we’ll discuss the fundamentals of each of these main reserve currencies. This also includes gold, which is a type of long-duration, store of value asset that acts more like a currency than a commodity.

US dollar

The US has the tremendous privilege of having the world’s top reserve currency.

But because of the US’s financial situation, where it’s increasingly having to “print” money to meet its enormous obligations that are increasingly coming due (not only public debt, but also other liabilities related to healthcare, pensions, and other unfunded obligations), it’s at risk of endangering that status.

The US is well past the point where all the money will be paid by taking a fraction of economic output (taxes) and/or spending cuts.

A country that does not have sizable reserves, a position the US is in, is vulnerable to not having enough of other currencies and reserve assets that the world values.

That means that the US is currently economically powerful because it can print the world’s most favored form of money, but would be highly vulnerable should it lose its reserve currency status.

People, which importantly includes many international entities, wanting to hold dollars through US Treasury bonds means cheaper borrowing costs.

This allows the US to live beyond its means and provide the country and its citizens with an income advantage.

It’s one of the reasons why US incomes have tended to trend around 20 percent higher on a per-capita basis relative to other developed countries.

The USD’s reserve status also conveys operational powers, such as having control over the world’s predominant clearing system.

China is positioning itself to gain power over time. China’s goal is to become the world’s top superpower. And to do so it will want the world’s primary reserve currency.

Overholding of dollars

US dollar holdings in foreigners’ portfolios are too high in relation to what they ideally should be.

These holdings are most importantly within portfolios controlled by governments, including the reserves of central banks and sovereign wealth funds, and large institutional funds.

USD holdings are too high relative to a variety of long-run measures:

i) The size of the US economy (gross domestic product) relative to the world economy

ii) The capitalization of US debt markets relative to the capitalization of other markets

iii) The asset allocation that international investors and reserve managers would want to have in order to more prudently balance their portfolios

iv) The reserve currency holdings that would be suitable to meet the needs of trade and capital flow funding

USD-denominated debt is high relative to all these measures. But, as mentioned, reserve currency status declines with a lag relative to the overall empire’s decline along various measures (e.g., economic output, trade, military power).

Typically, but not always or necessarily, a better system is created first.

The dollar is perceived as a safer asset than is justified and US dollar borrowings are disproportionately large.

Reserve managers, central banks, and others who are responsible for determining what share of their holdings should be in what markets and in what currencies collectively are not going to want to increase their share of dollar reserves.

This is especially true as the US needs to issue larger and larger amounts of debt (bonds) to cover its obligations.

In fact, many are considering reducing their exposure to US debt outright.

If this happens, it will require more purchases of this debt by the US central bank, the Federal Reserve. This will devalue the dollar.

The amounts that need to be produced are not likely to see adequate demand from private domestic investors or international buyers. The Fed will have to buy it as part of its monetary policy operations. This effectively means “monetizing” it.

On top of this, the financial incentives to hold this debt are low because the nominal yield on it is not very high and there’s a negative real yield.

If yields are 0-2 percent and inflation is 2 percent or higher, it’s effectively wealth destruction. People buy financial assets because they expect these assets will enable them to convert these holdings into goods and services down the road.

In the circumstances surrounding the US-China conflict, holding another country’s debt when you have conflict with the debtor is not as desirable as it is when relations are better.

China holds less than five percent of all US Treasury debt, but it’s certainly a risk.

Other countries know that the same actions taken toward China and their holdings of dollar assets could also be taken toward them. Accordingly, the perceived risks of holding dollar debts are higher. This can reduce the demand for them.

Currently, US net external debt as a percent of GDP is over 40 percent. No country has maintained that without a devaluation to help relieve debtors.

The US dollar’s role as the world’s leading reserve currency relies on its ability to be exchanged easily between countries and also work well for most countries to use it to transact in and as a store of their savings.

Therefore, the extent to which US policymakers place controls on the way the dollar can flow (sanctions), or run monetary policy in ways that are in conflict with the world’s interests relative to the US’s own interests, the less desirable the dollar will be as a reserve asset.

The basic takeaway is that a lot of elements are stacking up that are against the long-term value of the dollar.

But at the same time, the dollar is so widely used that it’s more valuable and difficult to replace in a short period of time.

Dollar weakness is likely to transpire over a longer period.

Testing the limits

The US is testing the limits of how far they can push the dollar to their advantage:

i) the dollar being weaponized through sanctions to help the US get what it wants and protect its interests

ii) producing a large amount of dollar-denominated money and debt

iii) fueling its borrowing through negative real interest rates on the debt (which disincentivizes people from wanting it), and

iv) having a monetary system where the value of the money is based on the federal government’s authority alone

Nobody knows what the ultimate limits to these actions are. And once these limits are reached it’s already past the point of rectifying them.

The US has to issue a large supply of debt relative to the demand. This has the effect of either pushing up the yields on it or devaluing the currency.

The latter is eventually favored, as it’s less painful to devalue money than let a lot of people and entities go broke.

Currency devaluations can also feel good in various ways. It’s stimulative to nominal activity and makes certain types of assets go up in nominal terms (e.g, stocks, gold, commodities; though it’s bad for bonds and the overall value of money).

The Fed won’t want interest rates to climb because keeping nominal interest rates below nominal growth rates maintains the spread necessary to keep the economy going. (To be more technical, debt service payments need to remain lower than incomes, saleable assets, and new borrowing.)

So, in a “free market” all the debt creation might signal a bad environment for bonds. But if the central bank wants or needs to buy it all, they’ll look to devalue the currency instead.

It’s politically difficult to raise taxes beyond a point. It impacts incentives and capital flows. People take measures to avoid them or vote out those governments.

It’s more discreet to devalue people’s money and has the aforementioned benefits.

The US government, through its deficits, and the Federal Reserve are basically running a giant experiment to see how much money and credit can be produced through the dollar’s reserve status without breaking the system.

For now, the US has the clear edge in the “capital war” currently as it pertains to its multi-conflict front with China. The dollar’s reserve status far exceeds the renminbi’s and that’s a big advantage.

But it’s clearly venturing into very risky territory given the supplies of dollar-denominated money and debt currently being supplied and the limited relative demand for it.

This doesn’t mean that anyone can be confident of the short-run trajectory of the dollar or its value as a reserve currency.

But the dollar’s relative proportion of global reserves will inevitably come down over time.

Euro

The euro is a type of pegged currency union that is weakly structured by unifying many different countries’ together that have quite different economic conditions. It is difficult for individual European countries to pursue monetary policies that are best in light of their own conditions.

This produces a currency that tends to be too weak for a stronger economy like Germany, and too strong for weaker economies like Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece.

European countries are highly fragmented on a number of different issues, both within and between countries, and the region is weak both economically and militarily.

Developed Europe grows at a slower rate than the US economy, is no longer on the frontier of productivity as it was in decades and centuries past, and its share of global growth is falling from its current level of about 15 percent.

Gold

Gold is a popular reserve asset. It has a track record going back thousands of years where it’s been used as money throughout time. Because it has worked for such a long time it is valued as a store of wealth.

Prior to 1971, during the Bretton-Woods monetary system, and in many other societies and empires before then, gold was the foundation on which money was based on.

To a lesser extent, silver has also been used to back up the value of money. Precious metals have helped countries refrain from creating money and credit too profligately and to ensure some level of collective fiscal responsibility.

Gold and silver are by no means perfect to peg a currency to, but are generally chosen as they don’t have wild swings in their demand.

But at a point, the amount of IOUs on gold (and other precious metals) becomes too high relative to the supply. The need to create money and credit overwhelms the desire to retain such monetary discipline.

Either the convertibility factor between gold (and/or silver or other precious metals) and the currency is increased or the link is broken altogether.

The US went through this delinking in 1933 and 1971, as can be seen in the graph below comparing reserve currencies against gold over time.

Gold is a non-credit dependent asset so it bears no risk from being excessively “printed” unlike fiat currencies. For this reason, gold functions similarly to the inverse of money.

As currency and reserves in circulation increase, the price of gold often follows over the long-run relative to whatever currency it’s being marked to.

Gold’s popularity tends to gain when the real returns on financial assets decline. It’s a type of currency hedge and long-duration store of value.

Gold is commonly thought of as a cash alternative.

Since 1850, interest-bearing cash has returned 1.2 percent annualized in real terms. Over that same period, gold has returned 1.3 percent annualized in real terms.

The gold market is limited in size and relatively illiquid. Its value is more volatile than most developed market currencies. So its use as a reserve asset is limited in accordance with that.

Japanese Yen

The yen has many of the same financial issues that are plaguing the US and its currency.

This includes a lot of debt that is growing quickly and being purchased by its domestic central bank (the Bank of Japan) through “printed money” such that it’s paying very low interest rates in nominal and real terms.

At the same time, Japan is not a leading economic and military power. It currently accounts for around five percent of global GDP, and it’s losing share as time goes on through low productivity rates and falling population growth.

The yen is also not widely used or valued outside Japan.

British pound

Before the US dollar became the world’s reserve currency, there was the British pound. The British empire surpassed the relative power of the Dutch empire somewhere in the mid-1700s.

The UK is now about only three percent of global GDP. It has fiscal and current account deficits and has relatively weak overall power geopolitically.

The pound is comparable to the yen as a share of global reserves at about five percent, still above its relative share of various economic measures for historical reasons.

Chinese renminbi/yuan (RMB or CNY)

The renminbi has been only a minor currency so far.

But its relevance is expected to increase over time given. China is the second-largest economy and has the second-largest stock and bond markets globally.

It has the largest share of global trade of any economy. Its economy is the second-largest and is projected to be the largest within the first half of the 21st century.

The Chinese renminbi/yuan is the only main reserve currency that makes sense on the basis of its fundamentals, unlike the dollar, euro, yen, and pound.

The US was the dominant economic power in 1945 and didn’t have a comparably sized economic competitor at any point in the last 100 years until recently.

Now it does in China, which is of increasingly similar size and it is also growing more quickly. On its current track, China will soon be as dominant an economic producer as the US was following the World War II period.

The RMB has been managed by Chinese policymakers to be approximately stable versus other currencies and on a purchase price parity (PPP) basis. Its foreign reserves are also large.

On top of that, unlike the other reserve currencies, the RMB doesn’t have a zero percent interest rate or negative real interest rate. It still has a normal interest rate and a positive-sloping yield curve.

China does have an indebtedness problem. But the debt is denominated in local currency where it can be controlled.

It will be restructured over time through a combination of write-offs, lowering the interest rates, elongating the durations, and changing who’s balance sheet it’s on (e.g., the central bank buying the debt if necessary).

China also doesn’t have the problems associated with debt monetization that the other countries do, which are stuck at zero and near-zero interest rates. So China’s money is relatively sound.

The main drawbacks to the RMB are the following:

– It’s not widely used globally. Not many people transact in it, save in it, or use it for investments.

– China has a different way of operating internally than Western democracies and Japan. Its type of top-down system doesn’t have the widespread trust of global investors. Some believe the Chinese system is not hospitable to good returns on investment given the government’s desire to control how various types of resources are allocated.

– Its capital markets are not yet as well developed even though they are large.

– Shanghai and Shenzhen are not yet considered global financial centers.

– China’s payments clearing system is not yet well developed.

What the decline/loss of US dollar reserve status will look like

We don’t know when the dollar will decline significantly as a reserve asset.

But we do know what will happen when it does. And there is little policymakers can do about it at that point.

It will involve:

i) People wanting to sell dollar-denominated debt and move their wealth into different countries and currencies and store of wealth assets.

ii) People wanting to borrow in dollars to take advantage of cheap funding to help them generate higher returns.

The Federal Reserve will have difficult trade-offs to make.

It will either need to:

a) allow interest rates to rise to high levels to defend the currency – that is, compensate investors enough for holding it – or

b) print money to buy the debt, which further reduces the value of the dollar-denominated money and debt.

Central banks almost always choose the second choice in printing money, buying the debt, and devaluing their currency.

It can’t allow rates to rise to such levels that crush economic activity, so it chooses to devalue the currency.

This process typically goes on in a self-reinforcing way because the interest rates the government is paying on the money and debt are not enough to compensate investors for the depreciating value of the currency.

To get the currency to bottom, policymakers need to choose an interest rate on the currency that offsets both the inflation rate and depreciation rate of the currency (based on the underlying capital flow) to provide a positive real yield.

But that’s typically painful because of higher credit and debt servicing costs, so devaluation is the common path.

This process typically goes on to a point where the currency and real interest rates establish a new balance of payments equilibrium.

In other words, this means there will be enough forced selling of real and financial assets and enough diminished buying of them by US entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

It’s a self-correcting process that works to rectify the excessive borrow-and-spend pattern of the past. Debts cannot rise above incomes, and incomes cannot rise above productivity indefinitely.

The social and political impacts of the US eventually paying the price for its excessive spending will be terrible.

It will mean that Americans can no longer spend as much because the US can no longer use its reserve status to borrow massive amounts of money to fund these expenditures.