Wealth Destruction: Why It’s Happening in Markets & How to Avoid It

Certain individuals holding certain types of assets in certain currencies face the biggest risk of wealth destruction today.

Markets provide the biggest opportunities – and the biggest risks – when there are unsustainable flows in liquidity in places where the prices discount earnings or economic scenarios that are not likely to transpire.

The risk of real wealth destruction involves the new paradigm of zero interest rates across the yield curve and what can happen when monetary policy and fiscal policy are unified are pushed to their limits.

Secular

There’s an ongoing rebalancing of economic power between the indebted, low growth Western countries and the faster-growing Eastern countries.

There are also various types of conflicts going on between the US and China that will play out over the coming years or decades.

More capital is flowing from West to East.

Because of the zero interest rates in cash and bonds that largely characterize the West, there are negative real (inflation-adjusted) yields and this is pulling the forward returns of stocks down as well.

When yields are very low – especially when purchasing power is being eroded – and these countries are creating a lot of money to get out of their intractable debt problems, this incentivizes more people to not want to hold the currency.

They will want to hold other alternatives, such as other currencies, other commodities, private assets, and other things that can be considered stores of value (e.g., cryptocurrencies).

So there’s the risk of wealth destruction in the assets and currencies of the countries that make up around 45 percent of global GDP today (US, developed Europe, Japan).

The most important themes today, which will go on for quite a while are:

i) Zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and quantitative easing (QE) being pushed to their limits, leading to tertiary forms of policy – monetary and fiscal unification.

ii) Divergences in the landscape between East and West.

iii) Having geographic diversification is more important than ever given the differing conditions across countries and currencies.

Secular landscape

There are a few main forces that drive economies. These are also producing divergences across regions.

i) Productivity

This is the rate at which people invent and learn how to do things better. Productivity is the source of real income and wealth over time.

Productivity is essentially what an economy boils down to at the most fundamental level.

ii) The business cycle

This is the standard cycle that’s generally controlled by central banks where they raise and lower interest rates to maximize output without generating excess price pressures.

These generally go on for 5-10 years or so. The recession dynamic normally occurs when the central bank raises interest rates to curtail inflation, which slows credit creation and financial speculation.

This causes the inflation and growth rate to fall, which eventually incentivizes the central bank to lower interest rates to stimulate the economy again.

iii) The zero-lower bound on interest rates

Throughout time, short-term interest rates hit zero. Economies are in a spot where the lowering of interest rates doesn’t stimulate credit creation.

The US was there during the Great Depression of the 1930s, 2008, and 2020.

US Short-Term Interest Rates

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

At this point, when short-term nominal interest rates can no longer be pushed lower, different monetary policy measures must be used.

The central bank (or central monetary authority) will typically begin buying longer-duration assets like government bonds (usually its own), riskier bonds and credit, and potentially even equities. This is commonly known as quantitative easing or QE.

When longer-term interest rates are at or near zero, then monetary policy must be coordinated with fiscal policy, as the standard framework has far diminished effectiveness.

The central bank provides the money and fiscal policymakers must decide who gets it.

This comes at the risk of devaluing a currency, which can bring with it higher inflation in both financial and real goods and services.

In some cases, it can result in inflation that ends up spiraling out of control, typically in countries that have large foreign-denominated debt, don’t have a reserve currency, negative real interest rates, and a history of high inflation.

iv) Politics

And there’s politics. Political decision-making influences how policymakers choose to use their levers to help aid the economy.

There’s also the general mix between much of the economy is controlled by the private sector (generally preferred by the political right) and the public sector (generally favored by the left).

When short- and long-term interest rates are near-zero, and the standard process of stimulating an economy no longer works, then more of an economy will be controlled by the government as a type of practical necessity.

How they fit together

With developed markets highly indebted and close to the zero lower-bound everywhere on their yield curve – including at or below zero depending on where you go – productivity will be low for the foreseeable future.

This is because the capacity to stimulate credit creation in the normal ways are gone.

Instead of interest rate adjustment, creating additional liquidity (money and credit) will be reliant on currency devaluation.

This helps asset prices. But asset returns are a combination of both price returns and the currency, not just nominal asset price movements alone.

For domestic traders, they care about buying power in the form of a real yield (i.e., nominal yields minus inflation).

For international traders, this entails movements in the exchange rate relative to their home currency.

High debts and near-zero interest rates limit how much spending and income growth can occur.

Moreover, reversing a downturn becomes more difficult when you can’t lower interest rates to offset a fall in growth.

This is why we’re in a world where monetary policy must be coordinated with fiscal policies to manage economies well.

On top of that, as traditional policy is more limited, populism has taken more of a role in the social and political order because of the various “gaps” that exist (i.e., wealth, opportunity, values, ideology).

This has created more internal discord within countries, a more polarizing social and political environment, and larger demands on the system to satisfy everyone.

Policy choices become more constricted when you have very low rates and high debt. So, money creation and debt restructuring become an increasingly likely way to relieve these pressures and help restore more policy flexibility.

The set of conditions for the East

When you look at the conditions for economies in the East, and especially China, you see a different outlook.

They have a normal interest rate and yield curve. They are growing more quickly than Western economies due to higher productivity rates.

This gives them more policy latitude to both stimulate growth and manage their cycles.

China and other Asian countries do have large wealth gaps, which can bring conflicts. But China’s culture and governance system can help manage them. Productivity gains will need to be broad-based to avoid this from becoming a bigger problem going forward where you have the types of social conflicts seen in the US and Europe.

The cultural differences between the East and West – and especially China and the US as the two main players – are creating more geopolitical tensions, which has implications for markets.

The upside is that each decouples in many respects (e.g., technology) – instead of feeding off each other’s progress and knowledge – and they each have their own spheres of influences globally.

The downside involves the various types of conflicts – trade/economic, capital, technology, geopolitical, military armament – spilling over into potential military engagement. This could be more limited, such as the fight over Taiwan, or potentially turn broader, which neither side wants.

Most circumstances involving a rising power coming up to challenge an existing power have led to a physical hot war – 75 percent of the time in the past 500 years. In other occasions, great pain have been taken to avoid them.

When one power rises to challenge another, physical wars usually ensue

(Source: Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs)

Conflicts generally go in stages.

Trade is usually the first domino to fall. It was in 1930 before World War II. The US applied tariffs back then, just as it did in 2017-18, though in a more minor way.

We’ve seen a little bit of the capital and technology conflicts.

Joe Biden’s election over Donald Trump may be seen as a move that could reduce some level of geopolitical antagonism with a less confrontational leadership style. Or the more boisterous style of Trump could be seen as a deterrent. Or make no difference at all.

But the key forces driving the various disputes and challenges are still in play. How political relationships are managed is very important, but elections don’t change many of the ongoing, big-picture realities.

China’s growth and its unique culture and top-down governance doesn’t fit in neatly with a US-centric world order, so there will be conflict no matter who is in charge. These tensions will continue to build and they will need to be dealt with one way or another.

Impacts on markets

A trader or investor might interpret this situation in that it’s dangerous to bet too much on one side or another (the US and its allies or China and its allies) given a future that is likely to be more hostile with potentially more bipolar global influence rather than the US and its allies dictating the world order.

Decoupling between the two sides might also bring greater diversification effects than normal instead of the general assumption that all capital markets are increasingly intertwined.

A rising East and setting West?

These divergent secular influences – a rising East against a sagging, indebted West – have implications for asset returns and capital allocation.

The West has engaged in a massive amount of monetary stimulation and other liquidity programs. This is particularly true in the United States due to the “exorbitant privilege” of having the world’s top reserve currency.

This has led to a lot of cash in the system, which is pressing yields down on all assets.

This is less true in markets like China where yields are more normal, which is getting more people to invest in Chinese assets.

The East, by and large, has better balance sheets, more productivity, more policy flexibility, and the least amount of money creation and currency devaluation.

This also means that their higher asset yields are at a bigger discount relative to countries that have the following mix:

– zero and near-zero cash and bond yields

– lower productivity (less growth)

– lower policy flexibility (less ability to counteract economic downturns)

– more internal social and political conflict

– increasingly dealing with this challenging mix through monetization

The Western countries dealing with these circumstances are increasingly moving toward what countries and empires typically do when faced with such a mix – a monetary and debt restructuring.

So, at the least, this calls for some level of geographic diversification to help balance the risks. It is also helpful to have some level of currency diversification.

Ongoing wealth destruction in real terms

The issue of low asset yields – not only on cash and bonds, but increasing risky assets – and printing a lot more money to relieve debt pressures means the genuine risk of real wealth destruction.

There’s the creation of a lot of debt that is supported through the creation of money. This is used to get money into the hands of people to help keep the social order normal and prevent languishing economic conditions or potentially a revolution of some sort.

There’s also the need for this to continue. When you create money to fund government debt, it lessens the value of that money and debt. It’s a discreet way of transferring wealth, as it doesn’t involve tax hikes or spending cuts.

This is inherently necessitated by an environment where interest rates are at zero everywhere along the yield curve, such that normal stimulation doesn’t work.

Looking toward economic history

The circumstances we’ve personally experienced are often different than the ones that have been experienced in other generations and lifetimes (and other societies).

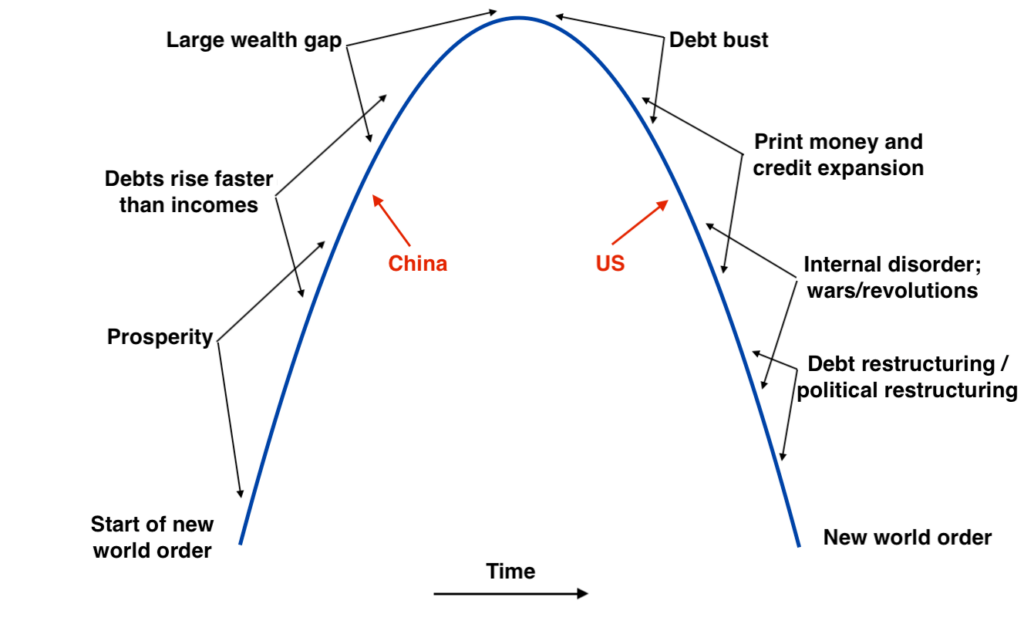

For anyone from the United States, most of their thinking is conditioned from the 1945 period on forward. It’s been the American world order and there have been great gains in equities and real wealth.

The 1945 to 2008 period has been the upswing of this conceptual arc. We’re now in the downswing as it involves money printing and increasing social and political conflict.

The generation before that experienced a 35-year period that was very different.

You had two world wars and a depression sandwiched in between them. World War I gave way to the debt-fueled prosperity of the 1920s.

The inability to service all that debt led way to an 89 percent drop in the stock market from 1929 to 1932 and a lot of economic pain, and internal and external conflict in the 1930s.

That gave way to a global military war starting in the late-1930s, running six years, with the subsequent restructuring of the world order.

Studying back hundreds of years can help give enough of a perspective to see how analogous times were experienced, including capital market outcomes.

Throughout the past several hundred years, the current mix in the Western world (zero interest rates, high social and political conflict) has been experienced many times.

You get a reflation, currency devaluation, and government guarantees of the efficacy of key economic entities and financial intermediaries.

Debtors are favored over creditors. One person’s debts are another person’s assets, so creditors see wealth destruction. This is often discreetly through currency devaluation (being paid back in depreciated money) and sometimes explicitly through asset write-downs and debt restructurings.

Wealth destruction has been seen repeatedly in every financial asset as countries take steps to help rectify bad economic conditions and ensure some semblance of stability.

Four stages of reflation

The reflation generally goes through four stages, if necessary.

i) Monetary stimulation

ii) Fiscal stimulation

iii) Debt restructuring

iv) Monetary restructuring

If monetary stimulation doesn’t work – i.e., lowering interest rates and, if necessary, buying financial assets – they move onto fiscal stimulation.

If that fails to get a reflation going because the debt and liability burden it too high, there’s a debt restructuring.

If that doesn’t work, there’s ultimately a monetary restructuring.

In almost every case in recent history (past 200 years), reflation relieved the economic distress. It’s a matter of how deep policymakers have to go and the impact it has on creditors and other asset holders.

Every asset class is vulnerable, but some more than others

Every asset class in history goes through a period of real wealth destruction of 50 to 80 (or more) percent.

This also includes cash.

Even though its value isn’t very volatile, cash is a risky asset to hold long-term given its purchasing power goes down over time. This is even if inflation manages to be low and stable and in some cases it’s not.

The risk in cash and bonds

Cash and bonds are already destroying wealth in real terms through negative real yields.

The printing of money is largely being used to replace lost income and not to make productive investments.

This is reducing the value of currencies at the same time the nominal return of holding bonds is about zero throughout the developed world.

Combining all this with the wealth, opportunity, ideological, and values gaps, to go along with rising geopolitical conflict, means the pressure to borrow money, issue debt, print money to fill in the gap, and raise taxes in whatever ways possible will be a reality until the monetary system breaks.

We’re in a period where there’s the pressure to create money and devalue it, and the determination of where that money will be directed will be dictated by the government.

It’s a question of how much will go toward income replacement and how much will go toward raising economic productivity.

Economic productivity helps to pay for itself if the productivity benefits exceed the costs, especially if these productivity benefits are broad-based.

Most of what’s being discussed here is geared toward a US-focused view, but the European Union has its own situation with this, as does Japan and Great Britain.

Japan and Great Britain are on the downward slope of their empires, and their currencies (yen and sterling) go with this process, but with a lag.

There are other countries that are in different parts of their cycles. Many countries are near the zero lower bound, while others are off of it and provide compelling real yields in cash, bonds, and equities.

Less important are the tactical moves — which are difficult to do well — and more important is achieving balance and strategic diversification across not only asset classes, but also countries and currencies.

Currency allocation will become increasingly important

US investors tend to think strictly in dollars and most put the bulk of their wealth in equities.

Dollars and stocks have been a fairly decent recipe throughout their lifetimes. The USD has been a global reserve currency. Stocks have had many bad downturns, but have ultimately gone up throughout most people’s lifetimes.

But, by and large, most traders and investors think a lot in terms of their asset allocation – e.g., what stocks do I buy? – and not enough attention to currency.

When faced with difficult trade-offs, currency depreciation is a hidden way of easing a debt problem.

This is because you’re not overtly saying who’s paying the price. You’re not directly saying who’s getting taxed or who’s spending capacity is being altered.

So the political consequences are the least severe relative to raising taxes and/or slashing spending, which is alienating and people generally vote out those governments if pushed to a certain level.

A currency devaluation is also stimulative to the local economy in nominal terms and increases asset prices up in that currency. These seem like good things. So the wealth destruction isn’t direct, even though it’s a big deal.

It’s expected that China will continue to liberalize their capital account and manage the RMB less. They’ll want to increasingly free-float their currency to bring it along as a global reserve. Capital controls at any material scale work against that, and are ineffective for a country with a lot of international trade and growth.

Every great power throughout history has had a reserve currency. This shift of the proportions of global reserves from the standard reserve currencies (USD, EUR, JPY, GBP) toward the RMB (and gold) is likely to continue.

Cyclical forces

Liquidity overdrive

The amount of liquidity is high in relation to the supply of assets, bidding up their prices and bidding down the yields of just about everything.

No longer does it make sense to have a lot of money in cash or in bonds yielding such low returns, and indeed destroying wealth.

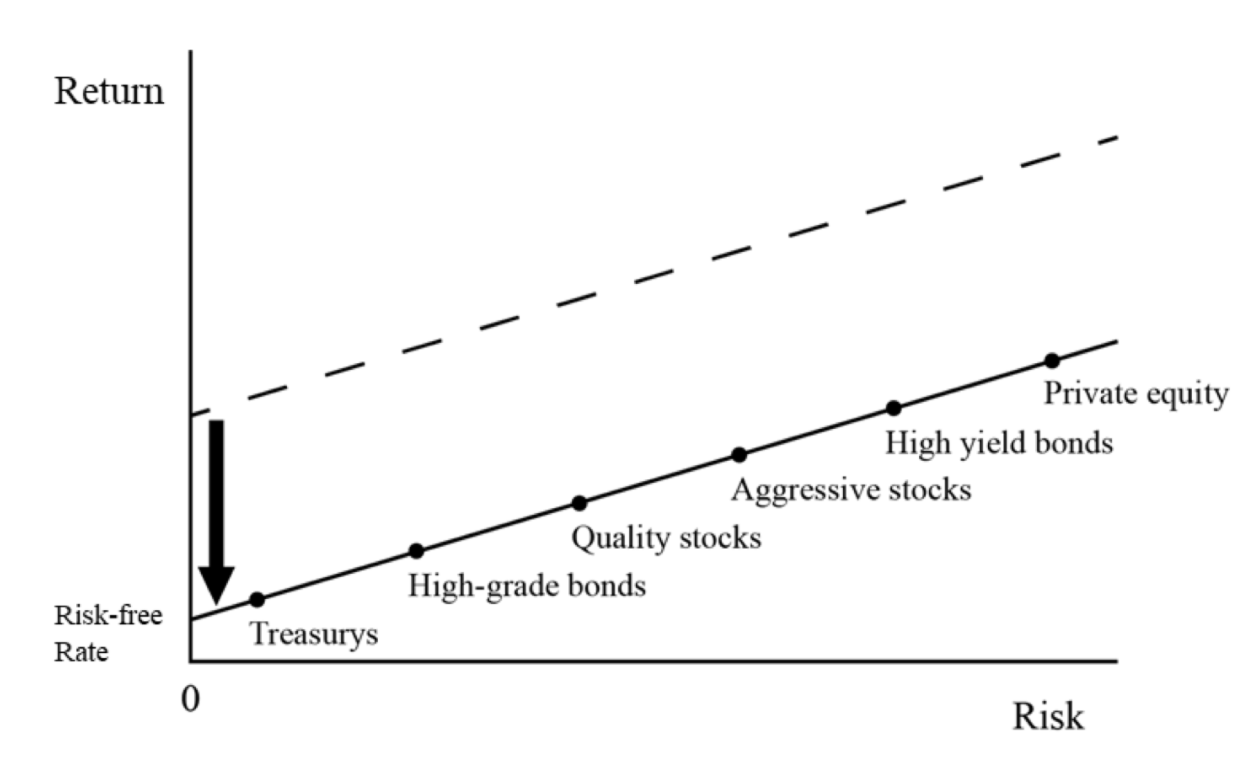

That said, it doesn’t favor a heavy allocation to stocks either, given their forward returns don’t look particularly enticing either. Stocks in the US have traditionally returned a bit more than three percent per year over the 10-year Treasury.

Stocks are also vulnerable to a rise in interest rates, which can come from higher inflation expectations and/or higher real yields, as people want to be compensated commensurate to the risk they take on.

So, you don’t want to just be in a single asset class. Or a single country or currency with the monetary shift that’s going on globally.

Wealth is always shifting. It moves around more than it’s being destroyed.

When asset classes decline, it’s typically not because a lot of actual wealth is being destroyed as it pertains to the whole. The bulk of it is just moving somewhere else.

It may be shifting into different assets, different asset classes, different countries, and/or different currencies.

When there’s a flood of liquidity, it favors a well-diversified set of assets.

2020 was the biggest year for markets since 2008 where the big economic forces were:

i) a big drop in incomes, which was…

ii) …caused by a public health crisis…

iii) …at the same time interest rates were at zero in all reserve-currency countries.

This led to:

a) Governments wanting to supply lost incomes.

This was financed from borrowed money that the central bank created. Supplementary liquidity and lending provisions created a big layer of liquidity, which propped up a lot of assets.

b) Assets that can be considered stores of value outperformed.

This includes things like consumer staples, which aren’t as vulnerable to big drops in income as they produce products and services that people need.

It also included a lot of technology companies, as people bet on these to yield the productivity improvements that add to economic growth and are less sensitive to overall macro conditions. In other words, things like interest rates, the price of oil, and so on don’t affect them as much.

However, very richly valued companies are highly susceptible to quickly falling into deep drawdowns. Bonds compete with stocks for capital flows.

If stocks with little to no earnings will provide very low yields for a very long time, yet safe bonds can get you comparable nominal yields, people will increasingly want bonds.

For example, many companies are trading at 50x to 100x earnings. The inverse of that is the yield (1 to 2 percent). If that’s the outlook for the next 5-10 years, people are going to find bonds that lock in that 1 to 2 percent increasingly more attractive.

So emerging tech can be very risky.

c) There was a wide divergence in outcomes between those who owned assets (“investors”) and those most impacted by the drop in spending (“workers”). This led to increased social and political divisions and a move back to the left politically in the United States.

Market drivers from a ‘sources and uses’ perspective

In a sources and uses framework, the basic sources of liquidity in an economy are money, credit, and income. These produce spending, reserves (savings), and purchases of financial assets.

M + C + I = S + R + F

(Money) (Credit) (Income) = (Spending) (Reserves) (Financial assets)

Netting out everything, even though there was a drop in income in 2020, there was more than enough of an offset in money and credit to replace the income. This produced a net surplus of income in relation to spending.

As a consequence, that excess went into cash that was earning little to nothing in nominal terms and less than zero in real terms.

All that needed somewhere to go.

As a result, in developed markets especially, you can expect a devaluation of cash relative to a portfolio that diversifies well among many assets over the long run.

With extra money on consumer balance sheets, the residential housing market has picked up and will continue to.

This goes along with reduced supply (going back to the financial crisis), mortgage rates at 2-4 percent, and more need, desire, and capacity to work from home.

Mispricings and Imbalances

In the markets, it’s not important whether things are good or bad but whether things are good or bad relative to what’s discounted in the price.

In other words, how are prices formed? And once they’re formed, what do they imply about the future?

The price of anything is the amount of money (which settles a transaction) and credit (a promise to pay) spent divided by the quantity.

A certain amount of currency is exchanged for a quantity of something. General movements in price are a result of demand for something in relation to its supply.

Money and credit are the basic building blocks of the system. They provide the funds for exchange that set the price, and also the funds to finance the spending that is discounted in prices.

From a tactical perspective, the best opportunities occur when unsustainable flows in money and credit form prices that discount in future economics or earnings scenarios that are unlikely to transpire.

Because of the very large amount of money and credit produced in certain countries (e.g., developed countries) versus the limited use of “printing” elsewhere (e.g., Latin America, Asia), there are big divergences across countries. This has led to very large impacts on incomes, spending, and the prices of real and financial goods.

Cases of unsustainable flows

Mexico, for example, saw a declining economy, falling liquidity, and did not offset the decline with money printing or fiscal stimulus. (This is because the peso is not a reserve currency, so most of said printing would have resulted in higher inflation and a balance of payments issue.)

Their spending and incomes collapsed, which in turn caused a big drop in imports. Taking into account the lack of spending on imports and fiscal and monetary balance sheets largely remaining unchanged, this enables their current account to move into a large surplus.

At the same time, their currency and asset prices fell. This caused asset prices and their exchange rate to implicitly discount these extreme conditions going forward.

Brazil also has similar dynamics to Mexico.

Any normalization of money and credit flows would discount a much better forward economic path and work to continue to relieve the liquidity squeeze that formed the current prices in the market.

Such imbalances can lead to big opportunities. Many of these opportunities will be outside of your home country and outside of your preferred or favorite asset class.

Because of a large number of previous currency declines and equity declines, and interest rate differentials between the US and other countries (Asia and cyclical emerging markets), this has made their discounted future cash flows cheap in USD terms (i.e., without hedging them).

For example, Japanese stocks unhedged in US dollar terms are valued at very reasonable levels.

Outside the country to country dynamics, you have massive amounts of USD currency and dollar debt being created, which is much higher relative to the long-term demand to hold it as a reserve.

This means, going forward, how one handles one’s currency exposure is going to be a big deal.