Portfolio Strategy: From Stocks and Bonds and Dollars to…?

Portfolio strategy has taken a big change from normal. Cash and bonds provide extremely low yields and this is having major impacts on where traders and investors go from here and how they construct their portfolios.

The nominal yields on government debt of reserve currency countries is very low to negative. We also know that central banks are going to target an inflation rate of at least zero percent, which means their real yields are even lower.

If a bond yields one percent and the inflation rate is expected to come in around two percent, that’s a minus-one percent real yield.

Cash and bonds, in these circumstances, are basically wealth destroyers.

Cash is one thing because everyone wants to get out of cash – the reason why people trade/invest – and/or borrow in cash to enhance their returns.

But bonds are another. The negative real yields of cash are basically locked in by moving out into bonds since their durations run on for many years, even decades.

If a standard 10-year bond yields 1 percent, that means you’re essentially signing up to destroy your wealth through that instrument by a little bit each year. (You can make money by speculating on the movement in interest rates, but that’s a trading strategy or alpha call.)

The real yields of government bonds are the lowest ever because of sovereign QE programs to help lower long-term interest rates to keep their economies going.

2008 was the start because of the financial crisis.

Real yields of cash are worse than bonds, as cash is zero to negative in all the main reserve currency geographies (US, developed Europe, Japan). They are nonetheless not as negative as they were during the previous monetization periods of World War I and World War II, with some overlapping years (after WWI and before WWII because of the Great Depression).

The low to absent yields are a problem because those owning these assets won’t see their funding needs met.

This includes important entities like pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, savings and money market accounts, and insurance firms.

These institutions meet their financial needs by holding some amount of conservative investment securities. With inadequate yields, they collectively will not be able to meet their obligations.

Hurdle rates of seven percent annually are not achievable when cash and bonds are 0-2 percent and stocks provide perhaps 3-4 percent in additional risk premium over those. And stocks are more volatile, which makes the path of future returns choppier with a higher distribution.

Bonds can still provide some diversification benefits since they do well in a particular environment (when growth and inflation run below expectation).

But nominal interest rates can only go so low, so nominal rate bond prices are close to how high they can go in price.

That means they become closer to a funding instrument than a traditional investment. That means more people will want to be short bonds rather than long if they are wealth destroyers on net.

Portfolio strategy: Does owning financial assets make sense?

The economics of having a lot of cash traditionally doesn’t make a lot of sense under situations when there’s a positive-sloping yield curve.

One of the main market equilibriums is that cash must yield below the rate on bonds, which must yield below the rate of stocks, and by the appropriate risk premiums.

People traditionally take cash and use it to invest in bonds, stocks, and physical assets where they can get a higher return.

But now the central issue with bonds is that you no longer get your 3-4 percent return over inflation like you normally do. There’s no spread, so the economics has become poor.

For international investors, who care about the value of the foreign currency relative to their domestic currency, when central banks have to print a lot of it now and in coming years to meet their debt and other cash flow-driven obligations, bonds don’t make a lot of sense either.

They don’t yield much or anything and the value of the currency is likely to decline long-term. This makes other assets more attractive to own, such as gold and things they’ll need like oil, copper, iron, and other commodities.

The entire idea of putting your money in the markets is to have it in a store of value that’ll enable you to convert it into purchasing power (of ideally higher value in real terms) than it is now.

You put up a sum of money for a stream of income going forward.

For example, if you invest in an asset for $100,000 and that gives you 5 percent return per year in earnings and inflation is 2 percent, you’re getting a 3 percent real return. Your money grows over time. You can take that $5,000 in return ($3,000) in real terms, and use it to invest back into the same asset or a different asset or use the money as income.

In turn, you can convert this into buying power down the road.

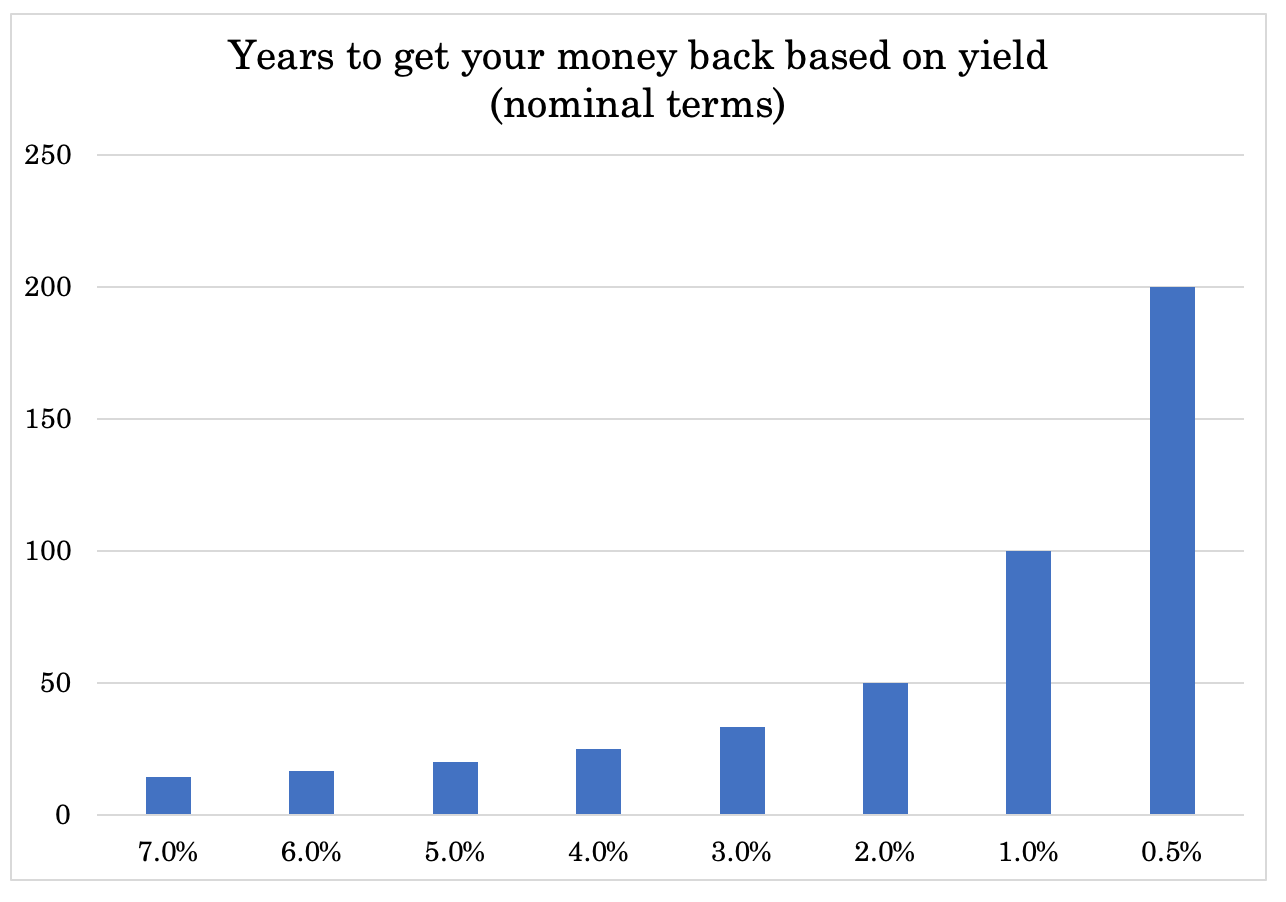

In all of the main reserve currency areas, you will need to wait anywhere from dozens of years (US) to hundreds of years (Europe, Japan) to get your money back from bond investments in nominal terms.

Taking into account inflation, which you need to do because you’re trying to at least conserve buying power and ideally get more of it, you’ll have to wait hundreds of years in the US to get your money back and you’ll never get it back in Europe or Japan.

In other words, the duration of these instruments has effectively become so long, as to be immeasurable in some cases because they no longer hold their traditional role as investment assets.

Unless you can cash in on a capital gain by buying bonds, if you buy bonds in the US, developed Europe, or Japan you are guaranteed that you will have less spending power in the future.

That means people will want to buy things that will get them inflation or better. That can mean the aforementioned alternative currencies (e.g., gold, precious metals), commodities, collectibles, or even making speculative investments on certain kinds of virtual currencies like bitcoin.

Bloated bond exposure

All of this comes at a time that:

i) the world is overweight bonds, especially USD bonds given the dollar is the world’s leading reserve currency, and

ii) lots of money and debt assets are being produced, especially in the US.

US debt held by sovereign wealth funds, central banks, and international investors are more than half of overall holdings. The euro is in a distant second place, followed by other reserves (e.g., JPY, GBP).

The US’s privileged position enables them to overborrow, which in turn has led to its exorbitant overindebtedness (which goes beyond just headline debt, but other obligations tied to pensions, healthcare, and other unfunded liabilities that put it around 15x GDP), which will eventually lead to threatening its reserve currency status.

Other empires have gone through it before, which means its citizens can no longer spend as much as they did before relative to their incomes.

Traditionally, this goes hand in hand with the rise of another power. This rising power develops its currency and capital markets at the same time the other power is overstretched economically and militarily, which makes it more vulnerable.

More capital is shifting from West to East. China’s capital markets are taking more from the US markets.

China’s share of international bond portfolios is still low relative to the size of its economy and based on its productivity rates (which are higher than those in the West), but growing quickly.

Based on the relative shares of world trade, economic activity, and sizes of their capital markets, US bonds are overweighted relative to underweighted China’s bonds. Over half of global debt is denominated in USD versus less than ten percent in RMB.

China is increasingly opening its doors to foreign investment. Moreover, their yields are normal relative to Western/developed market bonds.

China’s advantageous balance of payments situation also gives favorable forward returns on their currency. At the same time, the RMB is becoming more of a reserve through its internationalization.

The entire supply-demand picture makes for an adversely skewed set of possibilities for dollar-, euro-, and yen-denominated cash, bonds, and currencies.

These areas have incomes that are below their spending, which means lot of debt needs to be issued, and this imbalance will become more pronounced as time goes on.

This means one of two outcomes:

i) There’s too much supply relative to demand, which causes bond prices to fall and yields to rise.

ii) Central banks will have to buy this debt by creating money since price-sensitive, free-market buyers won’t take it all.

The first generally happens first because it acts like a signal to engage in the second.

The latter is bearish for those currencies, though it helps reflationary assets in relative terms — stocks, gold, commodities.

If bond prices fall…

If bond prices fall that could encourage additional selling of them.

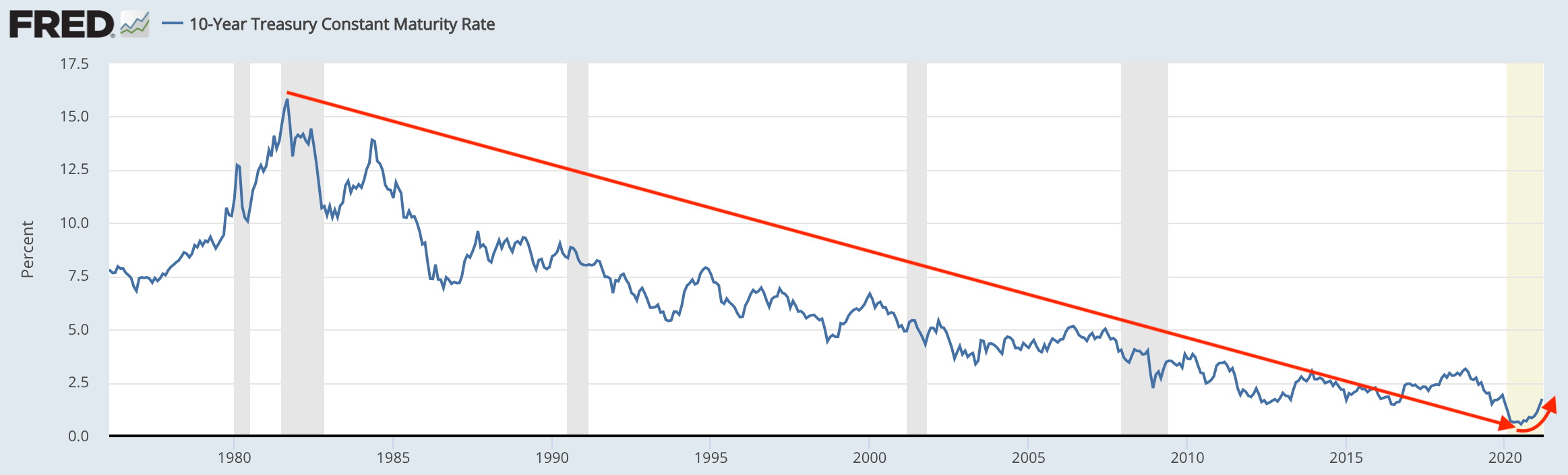

From Q2 1981 until 2021, bonds had a 40-year bull market that pretty consistently rewarded those long bonds and worked against those who were short.

Due to a natural tendency to extrapolate, this bull market created a large number of bondholders who felt comfortable continuing being long. There were only a few periods where being long bonds produced double-digit price declines.

If these holders want to sell these bonds due to:

- Lack of yield

- Concerns over the currency and profligate printing of money

- Recent price declines letting them know that being long bonds can be a painful trade

- Lower interest rates also lengthen the duration of financial assets, making them more vulnerable to large price declines should interest rates increase in the future

Then falling bond prices and rising body yields could create knock-on effects in all markets.

All assets are priced off a discount rate or risk-free rate, typically based on that of a safe government bond.

There are more than $80 trillion of US debt instruments of various durations. US Treasury debt is about one-third of this.

Holders of this debt need to decide whether they want to hold it and accept the horrible returns or sell them to buy something else that has better reward to risk characteristics.

Treasury bonds are largely held because they’re safe. The same goes for safe corporate bonds.

But if it doesn’t yield anything in real terms, there’s the currency and inflation issue to worry about (which are tied together), and the longer duration securities are subject to large price declines, they may realize that bonds are not actually that safe to hold.

The convertibility to cash problem

At any given time, the amount of financial assets relative to cash is large.

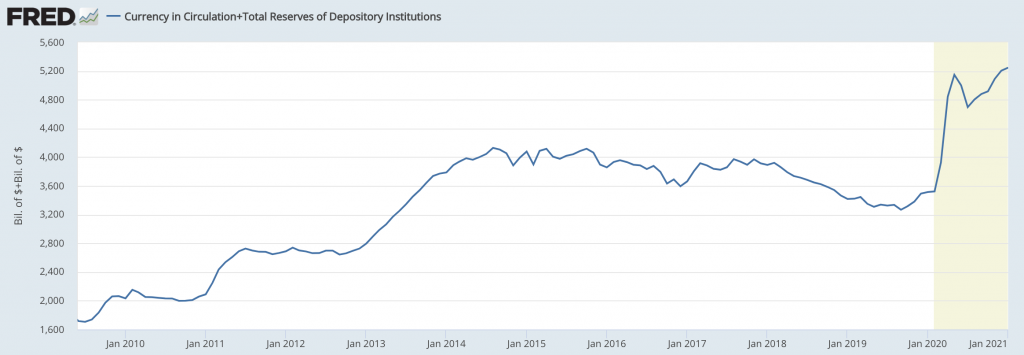

The total amount of money (i.e., currency and reserves) in circulation was only a little more than $5.2 trillion at the beginning of 2021.

Currency and reserves in circulation

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

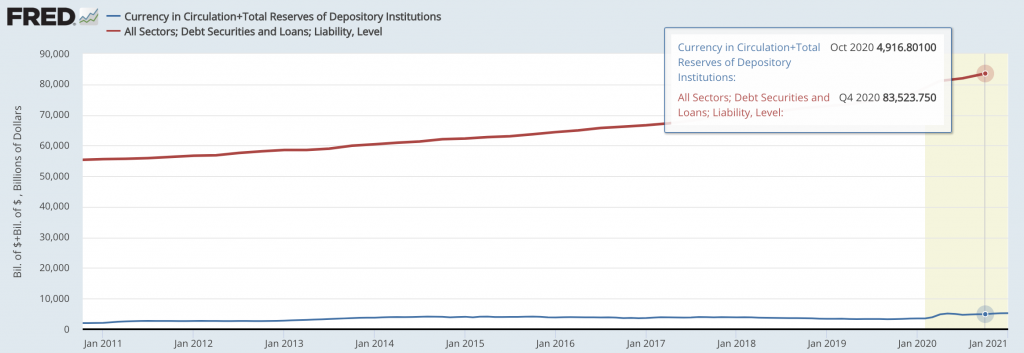

Yet the total amount of debt in circulation was close to $85 trillion.

Compared side by side:

Total debt, all sectors (red) vs. Total money and reserves in circulation

If these numbers were used as a guide, there are many more promises to deliver money (debt) than the actual amount of money available to deliver by a factor of about 17x.

On top of that, there is a lot of dollar-denominated debt that exists outside the United States, so this 17x figure (claims on dollars relative to dollars in existence) is smaller than the real aount.

The basic idea is that there are a lot of goods, services, and financial assets bought with credit and not enough attention to what they are promising to deliver and where they are going to get it from.

Accordingly, there is much less money than there are claims/obligations to deliver it.

Most holders of debt assets believe they can sell them to obtain cash and to buy “stuff” with it. That’s the basic purposes of holding financial assets – to convert them into buying power in the future.

The issue is that at these valuations it’s not realistic for a lot of these bonds to be converted into cash to be used for goods and services.

Any type of movement in this direction would essentially result in a “run” dynamic where people want to get out and there’s no stopping it.

There’s been these types of blips, where bond markets temporarily appeared broken, such as the 10-year Treasury bond jumping 11-12bps more or less instantly.

Any dynamic like this has to be rectified by the printing of money by the central bank to buy the bonds. This keeps yields in check and devalues the currency.

This will also include restructuring debt and government finances. It often involves increases in taxes on individuals and/or corporations.

Central banks will always print in the end

When bond yields increase, the actions of the central bank will depend on the circumstances behind the rise. If nominal growth is rising and nominal rates are following – but maintaining an appropriate spread – that’s acceptable so long as inflationary pressures aren’t too high.

When faced with rising bond yields due to a supply-and-demand imbalance that could create a rise that is more than desired with respect to economic circumstances, central banks will eventually create money and buy them.

This effectively enforces yield curve control that is essentially a cap on bond yields and comes with the trade-off of devaluing money.

This means cash is bad to own and good to borrow.

If the central bank provides low cash rates but allows an upwardly sloping yield curve, that can help generate external demand for bonds by making the rate on cash low relative to the rate on bonds.

This was the case during World War II in the United States.

Back then, the very high economic demands of WWII required capped funding rates to avoid US government debt – and eventual debt servicing requirements – from getting out of control.

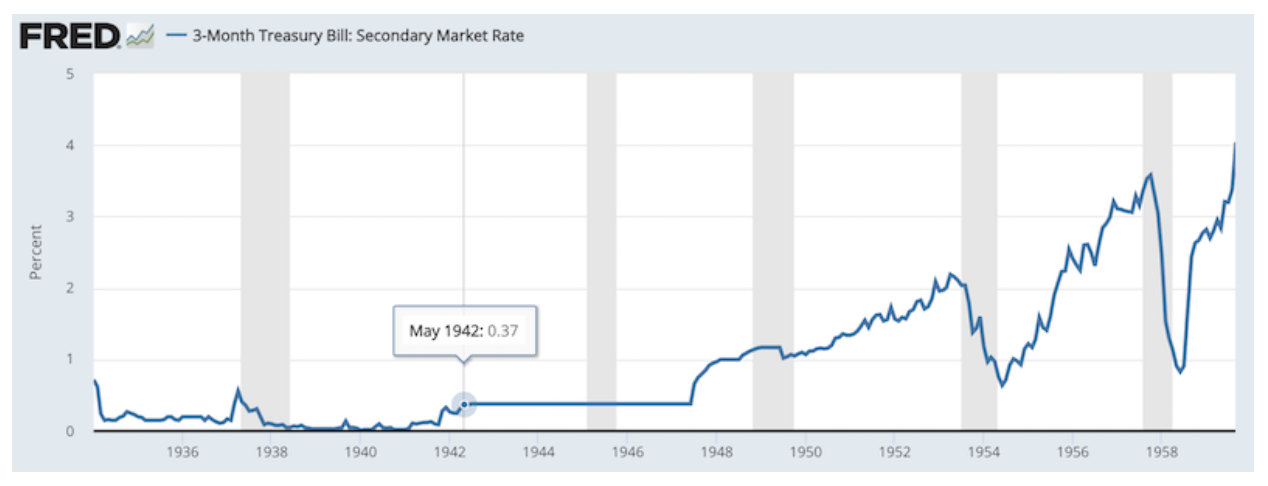

From May 1942 to June 1947, short-term interest rates were held at 0.375 percent.

Short-term interest rates

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

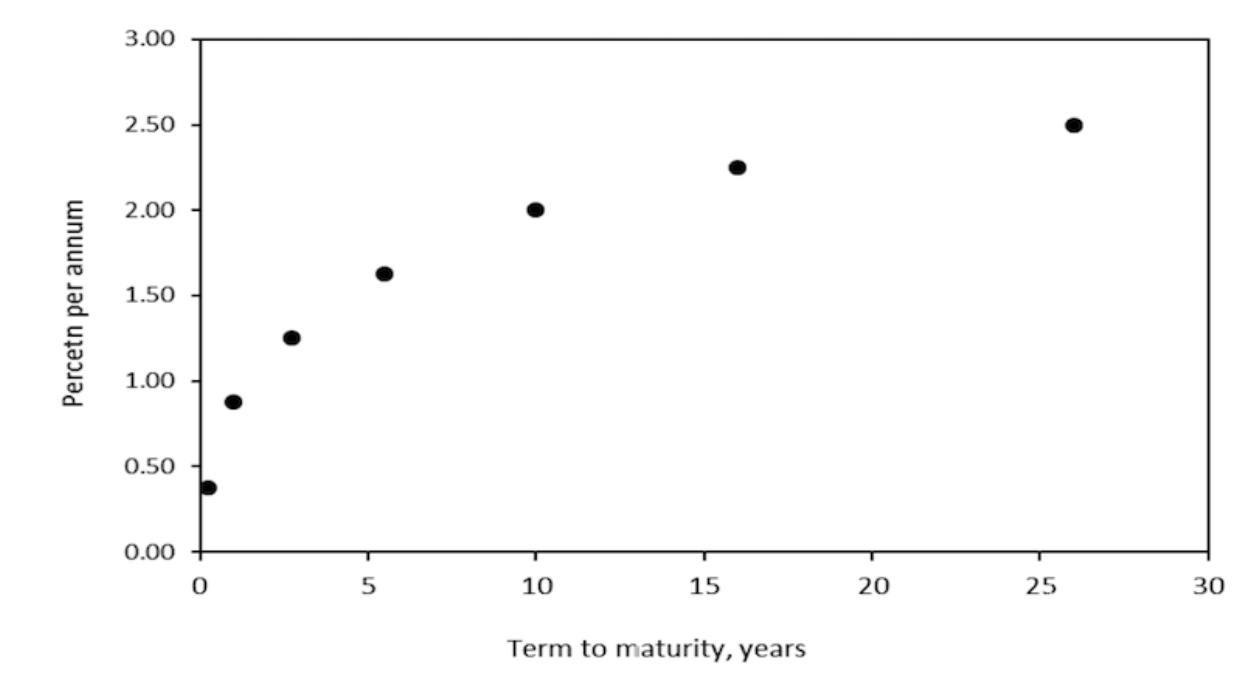

Intermediate yields included a 0.875 percent yield on 1-year bills, a 2 percent yield on 10-year notes, and a 2.25 percent yield on 16-year bonds. Yields of 2.5 percent were assigned to 31-year issues.

US yield curve during World War II period

(Source: New York Federal Reserve)

That meant borrowing cash to buy longer-dated bonds would’ve generated a spread of around two percent annually.

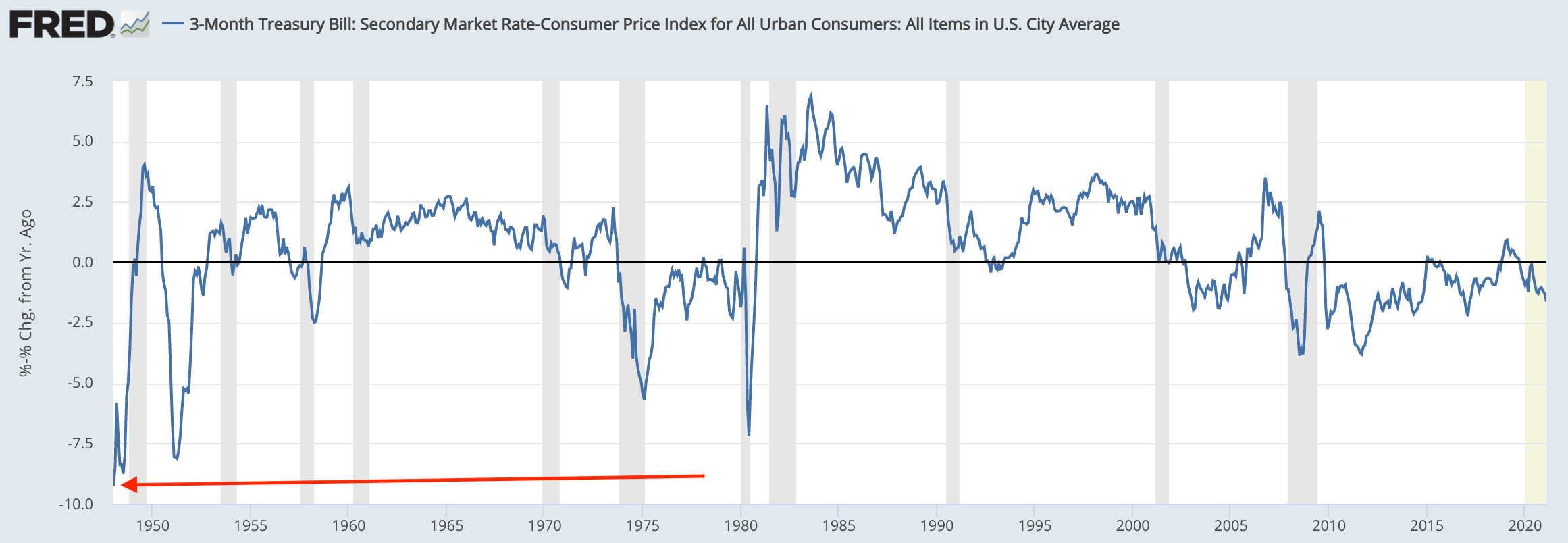

The level of inflation during this period made real interest rates very negative during the WWII and post-war period, a type of scenario not seen again until the inflationary 1970-1980 period.

US real (inflation-adjusted) short-term interest rates

(Sources: Board of Governors; BLS)

While keeping a positive-sloping curve helps generate a positive spread between cash and bonds, under this scenario both returns on cash and bonds are poor.

Capital outflows

To keep a lid on everything, it often means governments will undertake capital controls and outlaw store of value assets.

When capital is leaving the country it is more difficult for policymakers to manage.

It is popularly known among traders, investors, economists, and other market participants that central banks face a trade-off between economic output and inflation (the pricing of this activity) when they change interest rates and put liquidity in the financial system.

What’s not as well known is that this trade-off is more difficult to manage when capital is leaving the country – and conversely, easier to manage when capital is coming into the country.

Capital flows coming into a country allow it to increase its foreign exchange reserves, lower interest rates, and/or appreciate its domestic currency depending on how the central bank wishes to use this advantage.

When capital moves out, the central bank’s job is accordingly more difficult. It faces either higher interest rates, a weaker currency, and/or will need to expend its finite supply of FX reserves. (The US has few reserves in the form of other countries’ money.)

In a capital outflow scenario, less growth is achieved per each unit of inflation.

The 1930-45 period and other policymaker reactions

During this period, the Fed managed to keep yields low to keep borrowing costs under control.

They also banished gold ownership so people didn’t seek to store their wealth in a common alternative currency. Foreign exchange controls are also common to prevent capital from moving elsewhere.

Sometimes wage and price controls are put into place, but they tend to create distortions rather than provide solutions.

Shorting bonds as part of one’s portfolio strategy?

Such an environment might mean getting out of bonds or shorting bonds.

While bonds might be bad, central banks can keep cash even more unappealing.

And on top of that, policymakers could try to prevent capital from going to other countries, currencies, and other stores of value (e.g., gold, bitcoin).

What these moves portend

Historically, and logically, these moves are quite disruptive and signal a new paradigm in economies and markets.

It’s important to watch what central bankers do.

- Are they increasing their bond purchases at the same time interest rates are rising?

- Are interest rates rising and being led by long-term interest rates (i.e., 30-year rates in the US)?

- Is this occurring while the markets and economy are strengthening/strong?

If so, this means there’s a supply and demand issue in the bond market.

When the central bank buys bonds, what are the purchase amounts and what impacts is it having?

As more and more debt is coming due and:

- there isn’t enough free-market demand for them, and

- the central bank has to apply more money printing to alleviate the burden, and

- this has a lower pass-through effect into the economy…

…the worse things are.

This dynamic is all fairly classic and has happened repeatedly throughout history. It happened in the 1970s in the US, which in part is why the current period can be analogous to the 1960s going into the 1970s.

So, it’s really not that unusual. One thing we can be pretty sure of is that traditional nominal bond-heavy portfolios will not be as good as they once were.

US 10-year bonds will no longer provide the seven percent returns they have since 1972.

Portfolio assets’ performance: January 1972 to present

| Name | CAGR | Stdev | Best Year | Worst Year | Max. Drawdown | Sharpe Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Stock Market | 10.67% | 15.63% | 37.82% | -37.04% | -50.89% | 0.44 | ||

| 10-year Treasury | 7.05% | 8.02% | 39.57% | -10.17% | -15.76% | 0.32 | ||

| Cash | 4.65% | 1.01% | 15.29% | 0.01% | 0.00% | N/A | ||

| Gold | 7.62% | 20.02% | 126.55% | -32.60% | -61.78% | 0.24 |

Debt assets’ lost appeal is following the standard cycle

Credit is an asset to the lender and a liability (debt) to the borrower.

It conveys spending power that can be used for goods, services, and financial assets.

This helps create productivity, or the means by which living standards rise (“the economy grows”).

In the up part of the cycle the debt is employed well such that there’s more output produced, such that the earnings produced offset the costs of the debt.

Debt obligations nonetheless create a time in the future in which you’re not only borrowing from the lender but from your future self. You have to pay it back and spend less than you otherwise might.

Once this process is set in motion it quickly begins to resemble a cycle.

When the economy is weak and policymakers are doing everything they can to get it going again, it’s a good idea to buy the standard “reflation” assets like stocks, gold, commodities, and inflation-linked bonds.

The stimulation (i.e., money and credit injections) will first go into financial assets before passing through into the economy.

The new capital created to relieve the economic pain pushes interest rates down relative to both inflation and the overall nominal growth rate of the economy (inflation + real growth).

This pushes financial asset prices up, which are the discounted present value of future cash flows.

Interest rates being pushed below nominal growth rates lowers the overall debt service requirements in relation to incomes. Paying debt back becomes easier.

All the new money and credit in the system helps investment assets and can even cause bubbles in certain speculative markets even if the real economy is still weak.

This period benefits “asset holders” over “labor”. It can also intensify social and political conflict, as it did after 2008 and led to more populism and impacted the types of leaders who got elected.

After the positive impact on stocks and reflation assets, real growth picks up and later inflation.

After the increase in real and nominal growth happens, then one should expect policymakers to think about pulling back on how much stimulus they’re giving the economy.

This was a big influence in 2018, about ten years after the financial crisis, most notably in February 2018 and in December 2018. Most financial assets were down that year because of central banks starting to tighten money and credit.

They realized they were too tight and couldn’t normalize interest rates the way they thought they could, leading to a big rebound year in 2019. (This was analogous to the rebound years of 1982 following a tight 1981 and 1995 after 1994.)

Providing all these monetary stimulants over years and decades creates large debt obligations. As these amounts build, risks also increase.

Debts rise faster than productivity, and these problems eventually come to a head.

The creditors (those who lent the money) want to get paid back with more buying power than what they gave. Borrowers are carrying around the weight of having to make these payments.

Eventually they become too large and have to be dealt with. Because the income (a function of productivity) isn’t there to service them, they have to be reduced. But it’s hard to do, as there’s no free lunch.

Sometimes the stress point is reached abruptly and this forces policymakers to act.

They inevitably favor the debtors over the creditors and asset holders.

This is not good for these entities, but it begins to reduce debt to income ratios and lowers debt servicing payments.

This comes through a combination of:

- Writing some of it down (one person’s debt are another’s assets, so someone loses income)

- Changing the interest rates on it to make servicing cheaper

- Changing the maturities to help better spread out the burden over time

- Changing who is responsible for paying it (often the government buys it from a private entity)

This process is also generally bad for financial markets and economies. Many people lose their jobs and incomes. It’s also bad for capitalist systems more generally.

When this happens, what people thought was an asset wasn’t really much of an asset at all. Many financial assets lose their value and buying power that can be derived from them are significantly reduced until sufficient monetary stimulation is applied.

There’s typically a political shift to the left during these periods. There’s not enough money to pay for everything, so raising taxes is typically a normal action.

There’s also a lot over who should get money and where it’s going to come from. The rich are a common target, who want to be defensive and commonly move their assets and/or themselves out.

We are currently at this point, which coincides with these types of battles over wealth/money, ideology/politics, opportunity (“haves” versus the “have-nots”), and values internally.

And is often marked by the rise of a foreign power (China) coming up to challenge a leading power (US), which leads to disputes over:

How to trade this environment and general portfolio strategy

Because cash nominally yields zero and is negative in real terms, having too much cash is not a good thing.

You want to have liquidity and not be stretched, but cash is the least safe asset over a long period of time as it gets eaten away.

Bonds are also not attractive when they’re at zero, negative, or near-zero yields. Bonds that yield less than two percent are not very likely to serve their purpose as even a basic store of value. Wealth is essentially getting destroyed in a lot of these instruments (i.e., reserve currency sovereign debt).

A bond is a promise to deliver currency over time, so it essentially locks in poor returns when their yields start to mirror cash.

This means it’s essentially better to borrow cash and buy higher-returning assets that are non-debt in nature.

The tax picture will also impact what capital flows where and that will have an important impact on where people will want to be and what they’ll want to buy.

The wealth tax possibility and its impact on markets

Policymakers will want to raise taxes because they’ll be short of the money they need. This will cause movements out of debt assets and into other stores of value and into other jurisdictions.

They won’t like this behavior so they’ll work to try to prevent these movements.

For example, the wealth tax proposed by Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren has “trap” provisions, such as a 40 percent “exit tax” for anyone who wants to forfeit citizenship to get around the wealth tax.

Forfeiting citizenship isn’t necessary to legally evade much or all of these taxes, but it’s one of the many forms of controls policymakers may try to use to prevent capital from leaving the country.

This could mean clamping down on gold, bitcoin, cryptocurrencies, and other store of value assets and foreign exchange controls.

Wealth taxes have been tried throughout history, naturally when governments become increasingly desperate for revenue.

1920s Germany was one such example due to their massive war reparations debts. Many evaded the tax by moving their money/themselves somewhere else.

Many of those who were subject to it on some scale had to go on payment plans because most of what we call wealth is illiquid. This means they had to sell off assets to make their payments because they didn’t have the cash.

Flows from publicly traded assets to those that are privately held and more dispersed is a common behavior. They are not marked to market, easier to hide, and easier to dispute the value of.

This bids up the value of real assets relative to financial assets.

Because of the way the government is taking a more aggressive approach to managing the economy, the US could be perceived as less friendly to capitalism and capital markets.

The government, by unifying monetary and fiscal policy, is taking a more practical approach to the situation and is necessarily taking over more of the economy when the standard way of incentivizing private sector credit creation (lowering interest rates) is no longer effective.

Wealth taxes of considerable size are not likely to pass in the US and face constitutional hurdles.

Only under limited circumstances can the federal government pass a form of wealth tax. For example, states and local governments can levy property taxes (a type of wealth tax), but the federal government does not.

The steps that policymakers are likely to take will be met by actions taken by capitalists to run from the places and assets where returns are not likely to be good, which will worsen the situation.

To simplify portfolio construction in this environment

You can benefit from a well-diversified portfolio that:

a) increasingly moves away from ostensibly “safe” low-yield debt assets that provide low to negative real returns, and

b) increasingly moves away from a portfolio concentrated in US dollars to one that is more diversified by different currencies, including various store of wealth assets.

This can include, but is not limited to:

- some stocks (especially those that don’t rely on interest rate cuts to keep their earnings up)

- gold

- precious metals

- bitcoin/cryptocurrencies

- commodities

- collectibles and tangible assets

- income-producing assets that can be held privately

- real estate, and other alternatives

Bottom line

A portfolio strategy that shifts away from traditional financial asset mixes (e.g., 60/40) toward one that holds more non-debt, non-dollar assets can make sense with the way the world is changing and where it’s going.

This type of portfolio will be better suited than one that is a stock/bond mix that is heavily concentrated in US dollars.

It’s also quite likely that US and developed market assets will underperform those in emerging Asian markets, including China. This is because of current yields and the balance of payments differentials.

Traders and investors need to be aware of likely capital flows moving from West to East and the continued pressure this will place on developed market economies.

This has implications for foreign exchange/capital controls. It’s also important to be aware of likely changes in tax policy.