Market Equilibriums: The Most Important Three

The financial markets and the economy are inextricably linked together. Understanding these cause-and-effect relationships and what market equilibriums are necessary to achieve is important to have a sense of where markets are likely to go.

The financial system is what provides money and credit into the real economy. Money (what payments are settled with) and credit (promise to pay in the future) are the means of payment that facilitate spending. Spending, in turn, changes demand and prices.

Movements in the economy and movements in the financial markets are a continuous process by which they work to find their equilibrium points. These movements are a reflection of adjustments in the supply and demand of goods, services, commodities, and financial assets.

High rates of return don’t remain for very long. Profits attracts competition. If something is very profitable, more of it will be produced, lowering the forward return.

If making the good is unprofitable, less will be produced until it becomes profitable. This type of process will quickly begin to resemble a cycle.

Broadly speaking, at the macroeconomic level there are three big equilibrium points that need to be achieved.

Also, there are two forms of policy that governments can use in order to achieve these objectives – monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Looking at these forms of market equilibriums and what policy choices must be done to achieve these, it is possible to estimate what will happen next both economically and within the context of the financial markets.

Key Takeaways – Market Equilibriums: The Most Important Three

- Economic capacity utilization can be neither too high nor too low

- The growth in debt servicing payments must remain below the growth in incomes

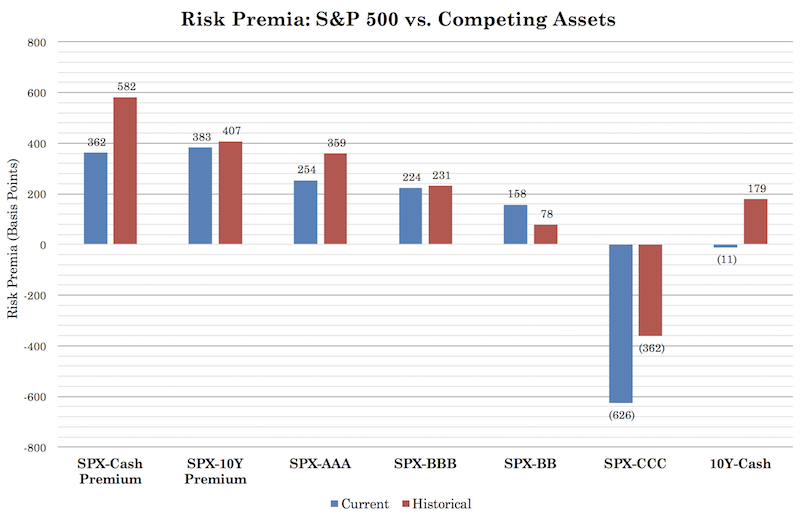

- Cash must yield below bonds, which must yield below equities and by the appropriate risk premiums

Let’s go through these market equilibriums individually:

1. Economic capacity utilization can be neither too high nor too low

If there is a lot of slack in the system – e.g., unemployed workers, unused infrastructure such as factories – then central banks and other policymakers will have large incentives to ease monetary policy to get utilization capacity up again. This is often called an “output gap”.

Economic activity becomes bogged down below its potential when the parts aren’t being adequately utilized within the system. This means more money and credit are likely to be pushed into the system through various means to get them allocated.

Central banks will be inclined to ease monetary policy through some combination of lowering interest rates, buying assets (to lower rates further out on the curve), or, likely eventually, by participating more directly in spending programs.

The exact laws and statutory mandates that central banks must abide by for various programs differ by jurisdiction. But easing or tightening policy to encourage or constrict credit creation is a cornerstone.

Politicians will be inclined to ease fiscally. This can mean a variety of things from public spending programs to tax cuts to deregulation and legal structural reforms and so forth.

Prices will adjust down in the economy and markets until using up spare capacity becomes profitable again.

On the other hand, when the labor market becomes tight and spare capacity is limited, then price pressures occur in the economy that can result in inefficiencies, such as prices that go up well in excess of wages. Inflation in anything is often stoked due to a shortage in supply of something relative to the demand.

When inflation heats up, or there is the belief that inflation will run too high, central banks will take measures to restrict demand growth through the tightening in credit conditions (typically by raising interest rates).

2. The growth in debt servicing payments must remain below the growth in incomes

Recessions, at least those in reserve currency countries where commodity and currency related shocks are uncommon, occur because debt servicing costs run in excess of income growth.

Borrowers default, which reduces spending power, which decreases wealth (i.e., asset prices fall), which leads to job cuts and a slowing in hiring, which reduces income.

Central banks must rectify this situation. In normal circumstances lowering interest rates fixes the issue. Debt servicing growth is dropped below the rate of income growth, and the process repeats itself.

Debt, in itself, is not an issue and shouldn’t be thought of in a black-and-white way. There’s good debt growth and bad debt growth.

If the debt is used in a way to produce more cash inflow (i.e., return on investment) than cash outflow (i.e., debt service payments), there is a net benefit for both parties involved – the borrower and lender.

If the opposite is true and the cash outflow begins to exceed the cash flow produced, that means the debt is not being productively used. That represents an unsustainable situation and denotes that changes will need to be made.

Credit growth must occur in a way that achieves balance – when both debtors and creditors benefit from the arrangement.

If credit creation is too slow, then spending and investing in the economy will be too slow and the economy will not reach its full capacity.

On the other hand, if credit creation runs at too high of a pace – that is, when debt growth exceeds income – then the level of demand in the economy will be too high. Debt problems will eventually follow.

For this reason, debt growth must be appropriately in line with income growth.

Moreover, incomes are volatile. So, it is difficult to accurately assess the level of income that’s precisely available to meet debt servicing requirements at any given point in time.

Accordingly, this is why having savings available is important to act as a buffer to deal with any shocks that reduce income.

At the household level, this means savings that are easily accessible, such as cash and cash-like securities. For corporations, this means having adequate liquidity to continue operations and avoiding over-leveraging. For countries, this is means having sources of strategic reserves to deal with shocks or prospective shortfalls in important goods – e.g., foreign exchange reserves, appropriate commodity reserves (oil, gas, and petroleum being the major ones). At the sovereign level, having a reserve currency is especially important as you can create more to fill in the gaps in income and credit.

Debt growth often runs above income when people extrapolate the past and expect the future to be very similar to the environment they’re familiar with.

To avoid this problem, debtors, creditors, investors, and policymakers need to ascertain what kind of return they’re likely to get by understanding the project or investment and the cause and effect relationships driving its value and futures returns. This ties in with the financial markets and is the subject of the next equilibrium point.

3. Cash must yield below bonds, which must yield below equities and by the appropriate risk premiums

The expected return of cash must be below the expected return of bonds, which must be below the expected returns of equities. These spreads must also reflect the appropriate risk premiums.

A risk premium is an expected additional return for investing in something, determined by factors related to duration, credit risk, liquidity risk, and other sentiment and behavioral inputs.

When you choose a stock over most forms of bonds you expect to be compensated for taking on higher risk accordingly.

The capital markets cannot function very well when these premiums are out of line for long periods. It will prevent households, companies, and governments from investing and funding themselves well.

This is part of what yield curve inversion gets at and why it’s talked about when it happens.

When a yield curve inverts, the return on bonds is lower than the return on short-term rates (i.e., the rate that is paid on cash or a cash-like instrument).

This throws a wrench into the lender-borrower relationship. If the funding costs of financial intermediaries are below the rate at which they can lend profitably, they will often choose not to do so and this will slow credit creation and economic growth.

In general, when these risk premiums are not there, it interferes with the incentives to invest, produce, lend, and borrow.

Economies function because people trade things that they have for things that they need or want.

In the markets it is the same thing. Investors are going to want to be compensated for taking on more risk with riskier assets. Taking on these risks is not attractive if there isn’t sufficient compensation involved.

The size of the relative risk premiums will work heavily to determine what capital will move to what assets. This will in turn work to drive money and credit throughout the financial system and economy. Financial intermediaries, such as banks, are always looking to obtain this spread.

Accordingly, this makes distortions in these premiums unlikely to last for long periods of time. In turn, this drives asset class returns and knock-on effects in the economy, such as credit and output growth.

In the economic system that we live in – at least in developed markets, by and large – one person’s cost of financing is another person’s return. This process is heavily controlled by a country’s or jurisdiction’s central bank.

They set the rate on cash (also commonly known as a reserve rate, deposit rate, or overnight rate). The central bank, through the commercial banking system, makes this cash available to those who are able to borrow it and generate a return beyond what they’ll pay in interest.

If the risk premium between cash and bonds and bonds and stocks is too high or too low, the amount of borrowing and lending will also be too high or too low.

Tight spreads between asset classes will lead to insufficient borrowing and lending activity. Wide spreads will lead to too much.

Typically, short-term interest rates are below the rate of return on both bonds and equities – or riskier, longer duration assets in general. This incentivizes people to borrow at the short-term rate to buy longer-term assets to profit off this spread. These investments could be capital spending projects such as factories or mechanical equipment, real estate, and traditional financial asset investments like equities, venture capital, or private equity.

Below is a representation of how stocks are priced relative to cash and various forms of bonds, and cash relative the US 10-year.

Because of the leveraging factor, these assets will tend to go up in price and reward those who take on the risk. This causes asset prices to appreciate.

Afterwards, income goes up, which makes businesses and consumers more creditworthy. This encourages more borrowing and pushes asset prices up further and these risk premiums down. Long positions in financial assets become increasingly leveraged.

At a certain point, the central bank will usually raise interest rates to cool off this process, often taking signs from a tightening labor market and/or increases in consumer prices.

When the cash rate is pushed above the expected returns of bonds and/or the expected returns of equities, this rewards investors for holding on to cash relative to riskier alternatives. Accordingly, lending and borrowing activity will slow and the economy will grow at a slower pace.

Normally, these positive risk premiums for equities over bonds and for bonds over cash holds true. However, that won’t always be true. Moreover, it’s not always prudent for that to be the case.

If cash rates were perpetually left below the returns of other asset classes, then risk-taking would get out of hand. People would have no fear in going out to borrow cash and own higher-returning assets to the maximum degree that they could if they knew it would always work. This would not be a sustainable set of conditions. Too much leverage will build in the system and it’s important for investors to have a healthy fear of risk.

When the US yield curve inverted in 2019 – both the 3-month / 10-year spread and later the 2-year / 10-year spread – many market participants criticized the Federal Reserve for being indifferent to it. While the Fed has been behind the curve and made an error in its assumptions of how much and how quickly it could tighten monetary policy in Q4 2018, managing monetary policy to the stock and/or bond markets is not necessarily the correct thing to do.

Having occasional periods where risk premiums run close together or even become negative helps to prevent excessive risk-taking and prevents the economy from running above potential for too long (which leads to eventual debt issues).

This means there will be occasional periods where the economy and markets don’t perform as well. Central banks have a large amount of control over when this occurs, just as they have reasonable authority over when periods are better for the economy and markets. They impact the spreads through their use of monetary policy. Q4 2018 was one of these periods.

Tying these market equilibriums together

These factors:

- equilibrating economic demand and economic capacity,

- keeping debt growth (more accurately, debt servicing obligations) in line with output and income growth, and

- maintaining the risk premiums between various asset classes in the capital markets

…fluctuate constantly above and below their equilibrium levels, often resembling cycles and elongated trends in both the economy and financial markets.

These market equilibriums also work synchronously. When one equilibrium is achieved, another often gets out of whack.

For example, when risk premiums between financial assets contract and go negative, this often means that the economy is reaching a point at which economic demand and capacity are in equilibrium. This is why you sometimes see strong economies accompanied by falling stock prices. Financial markets lead the economy.

When debt growth is put back in line with income growth, this often means that demand is insufficient relative to capacity, and risk premiums are too wide (i.e., asset prices are weak).

These equilibria do not remain out of line for long periods. If they are, circumstances will emerge that drive change back to them. For instance, when they are not at their appropriate points – e.g., capital and labor are not adequately employed – this often brings social unrest and changes in political regimes.

When the US was in the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s, there was not sufficient stimulation brought to the economy. This worsened the depression, stocks lost 89 percent of their value from peak to trough, unemployment was very high, and high levels of populism developed.

This resulted in the election of the populist candidate Franklin Roosevelt, after which policies of dollar devaluation and unusual central bank measures (i.e., the Federal Reserve purchased US Treasury bonds, much like what quantitative easing (QE) is today) were undertaken to rectify the imbalances. This leads us to the next section.

Inflation-Linked Bonds vs. Nominal Bonds

Inflation and inflation discounting also brings up another equilibrium to monitor:

- The yield on nominal bonds vs. the yield on inflation-linked bonds

Real Yield and Inflation Expectations

The risk premium on inflation-indexed bonds may or may not be considered attractive compared to the market’s discounting of future real yields of cash.

An upward-sloping real yield curve (nominal yield minus discounted inflation) means greater attraction for inflation-linked bonds at longer durations than nominal bonds, for example.

Equilibrium Movement in Real Yields

Real yields need to adequately compensate investors for the risks associated with inflation.

Comparison to Market Discounting

The attractiveness of the risk premium on inflation-indexed bonds is highlighted in relation to the market’s expectations for future real short-term interest rates.

Related: Inflation-Linked Bonds vs. Nominal Bonds

How governments can bring about these equilibria

Policymakers have two main ways of keeping these equilibria in line, monetary policy and fiscal policy. We’ll go through each one individually.

Monetary policy

The two main ingredients that facilitate changes in spending and the economy are money and credit. Central banks have the power to influence both their prices and quantities.

The price of credit is represented by interest rates. Interest rates are not the price of money, as commonly defined. Money is something that settles a transaction rather than opens up a liability account (as credit does). The “price” of money is the inverse of the price level, with its value decreasing over time due to inflation. This is why cash under the mattress is generally a bad idea or even cash getting an interest rate that doesn’t compensate for the inflation rate and any taxes paid on interest. Cash may not see it’s value move around much so it’s considered safe from a volatility perspective, but it’s the worst investment over time.

When central banks change these prices and quantities, this influence the values of financial and real assets, economic activity, and the value of the domestic currency relative to others and relative to alternative store-holds of wealth such as gold.

Central banks typically do this by changing short-term interest rates of by purchasing debt assets (to change longer-term interest rates). With respect to asset purchases, first, they start out with sovereign bonds.

This process works by putting cash (liquidity) into the system. Namely, the central bank buys these securities, which represents assets on their balance sheet. The holders of these securities – primarily commercial banks – gets cash (reserves) in return. This impacts the spreads between assets in the ways mentioned above.

Holders of these bonds want to buy something similar and move out over the risk curve. This helps create a wealth effect and is stimulative to the economy. The goal is to get it into spending, which helps support income, which supports further spending in a virtuous self-perpetuating cycle.

Central banks normally will ease policy in this manner when capacity utilization in the economy is low and debt growth is languishing.

This lowers cash rates (short-term interest rates) relative to the yields on bonds. To capture this widening spread, investors and financial intermediaries capture this spread. This bids up their prices and reduces their yields.

This is turn means the spreads between bonds and equities will rise as well (i.e., the risk premium will increase). So, stocks tend to increase in price in conjunction.

Because higher asset prices make people wealthier, they become more creditworthy. This encourages more lending activity and higher spending.

When central banks judge that debt growth is too fast and the capacity of the economy is running above what’s sustainable (such that inflation is rising), they will do the opposite and tighten policy. They will raise interest rates and run-off their balance sheets, or reverse QE.

This makes cash more attractive relative to bonds, and (usually) bonds more attractive relative to equities. (Equities are higher duration, higher risk securities than bonds and may do worse in a rising rate environment than bonds if corporate earnings don’t keep up in conjunction.)

Depending on the earnings situation and exogenous factors that can affect the day-to-day movement of asset prices, this can cause asset prices to fall or rise less quickly.

In turn, this makes lending less attractive when rates rise faster than the expected returns on investments. Lending and spending will normally slow, also causing economic activity to decrease in conjunction.

Types of monetary policy

Broadly speaking, there are three main forms of monetary policy:

1) Adjustment to short-term interest rates

2) Asset buying (also known as “quantitative easing”)

3) Joint fiscal and monetary policy. This can include debt monetization (central bank buys government debt and effectively pays it off) or stimulus directly targeted at spenders (commonly called “helicopter money”). This broadly falls under the current moniker of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) that’s settled into the mainstream when discussing fiscal and monetary coordination.

Interest rate policy has a broad influence on the economy and is the preferred measure. Decreasing interest rates allow central banks to make it easier to buy goods, services, and financial assets.

This helps ease debt servicing costs. Lower rates also decrease the discount rates at which the present value of cash flows are calculated (which form the prices of financial assets). This creates a wealth effect.

When short-term interest rates hit zero percent – or whatever lower bound is desired by a central bank, can be slightly positive to somewhat negative – they will move into quantitative easing.

They create reserves, a form of monetary savings, and buy debt and perhaps other forms of securities. This increases cash in the system and decreases the yield spread between cash and bonds. This pushes investors and savers into riskier assets, causing prices to go up to produce a wealth effect.

Quantitative easing works when risk premiums on bonds are high relative to cash and equities relative to bonds. It helps to lower the risk in financial markets more broadly.

It becomes less effective when these spreads close. Once the spreads on bonds are comparable to cash, or provide compensation insufficient for the higher level of risk (e.g., say between a Treasury bond and corporate bond of some duration and risk), then QE becomes less effective. This is because they can’t be pushed down much further.

This is often called “pushing on a string”. The ability to produce a wealth effect is diminished, as well as the capacity to increase spending and lending activity, and hence economic output.

When QE is exhausted then they must turn to a third form of policy.

The third form of monetary policy, which we’ve now moved into in the developed world, could include buying and retiring government debt or it could mean putting money directly in the hands of spenders and tying it to spending incentives. For example, to incentivize people to spend the money rather than save it, it could disappear after a certain expiration period.

There are various ways joint fiscal and monetary policy can be done in an infinite number of permutations, which we discussed in previous articles.

Fiscal policy

Governments, through fiscal policy, influence the economy through their expenditures on goods, services, infrastructure, and with policy measures with regard to regulatory and legal reforms and tax policy.

Central banks are responsible for determining how much money and credit are in the system. Central and local governments help determine how to split up the pie, in how wealth is redistributed through their particular policies, programs, and other measures.

There is a certain amount that governments will need to spend. They will do this through a combination of tax revenue and borrowing. These choices are often unpopular, given decisions must be made regarding how much to spend, tax, and borrow, and who gets what set of goods and services and what structural reforms get accomplished. This process influences the economy. When these decisions are made, it is inevitable that there will be some who benefit and some who may not benefit.

When governments spend more and/or tax less, this has a stimulatory effect to the economy. When the opposite is done – spending less, austerity measures, and/or spending more – this is restrictive to the economy.

When the Trump administration passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, this cut taxes for most individuals and corporations. When you cut taxes, people have more money to spend. Companies become worth more when they keep more of what they earn. This pushed up stock prices and economic activity.

The policies that governments make also influence behavior. This could be laws that govern the labor market or regulations that impact efficiency, security, and protections for certain economic actors.

Legal and regulatory reforms that remove restrictions on economic activity can help the economy, improve productivity, and better a country’s competitiveness in the world. Fiscal policies can either assist or hold back economic activity.

The policies that are chosen through fiscal and monetary policy can push economies toward these equilibria or away from them. Moreover, they can also adjust the speed at which they move toward or away from them. If policymakers move inappropriately, incapably, or without sufficient haste, this can drive the economy away from these equilibria. If their actions are expedient and appropriate, they can drive the economy and markets toward them.

By seeing which are in line and which are out of line, you can help to anticipate what monetary and fiscal policy actions are likely. When these shifts are anticipated, we can anticipate what the changes in the conditions will be for financial markets.

Conclusion

Economic and market equilibriums include:

Spending in Line with Output

This equilibrium is important for sustainable economic growth and low inflation.

It’s achieved when nominal spending growth aligns with the growth in the labor force and productivity.

In the context of the US, a nominal growth rate of around 4% is generally indicative of this balance – i.e., growth in line with capacity and inflation of about 2% (high inflation has negative impacts on productivity).

The equilibrium suggests that the levels of output and employment are appropriate relative to the output capacity and the size of the labor force.

Debts in Line with Incomes

An economy is less susceptible to major financial crises when debts are proportionate to incomes.

This balance is essential to avoid extreme financial vulnerabilities, such as a debt bubble or a credit contraction leading to a depression (i.e., a point where interest rates can no longer be lowered to stimulate an economy).

The equilibrium is not just based on broad averages but also sectoral and dependent on the health of key entities and intermediaries, ensuring that different sectors of the economy work together harmoniously.

Risk Premiums in Line with Risks

This equilibrium supports the efficient flow of capital in the economy.

For instance, a moderately upward-sloping yield curve encourages risk-taking for credit growth, while a reasonable equity risk premium relative to bonds fosters sustainable equity capital flow into productive enterprises, reducing the likelihood of destabilizing price movements.