Are Stocks Too Risky? What To Do

Traditionally, toward the end of bull markets, assets of the worst quality tend to take off. We’re also seeing this type of froth in certain pockets of the market.

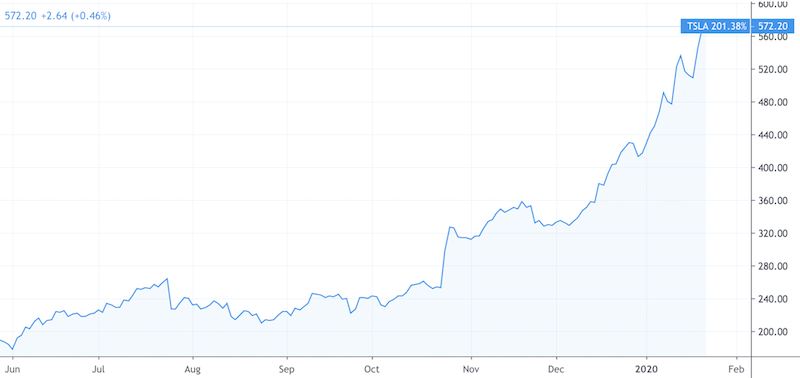

For example, Tesla, despite its poor balance sheet, difficulty in selling cars profitably, and its status as a car company (a capital-intensive, thin margin industry) has taken off in a rally reminiscent of bitcoin in 2017 and 1999 dot-com stocks.

Its price has risen more than 3x since its recent May 2019 bottom.

Companies that are hard to value, because their future cash flows are so uncertain, combined with some misunderstanding of what the company is actually all about, are prone to massive distortions in their valuations due to narrative.

Is Tesla a tech or software company that will eventually have fat margins, as its price extrapolates? Or is it simply just a niche auto OEM?

Is it actually profitable and turned the corner to becoming a “real company”? Or is the company’s representation of itself a function of accounting gimmicks, such as stretching its accounts payables, cutting its capital expenditures to conserve cash, shifting expenses to prop up gross margins, capitalizing operating expenses to the balance sheet, under-reserving for warranties to increase net income, and so on?

In terms of industrial output, its valuation is way out of whack. General Motors and Ford produce 40 times the number of vehicles with profits of $10 billion per year. Tesla produces a very small number of cars at a loss and is worth more than both combined.

WeWork rallied to a $47 billion valuation in the private markets by portraying itself as a tech company.

In reality, it simply sub-leases property. What does WeWork do that prevents other office space REITs from fetching the same type of valuations? That’s an important thing to get at to determine whether a wide divergence in valuation from its peers makes sense. Great business opportunities attract competition and it’s rare and hard for a company to have an everlasting advantage.

WeWork leases office space, then sub-leases it at a higher per-unit cost to capture that spread. Basically, they take credit and duration risk. It’s not any different from a financial services company.

There is no constraint on their growth except for capital, not unlike a bank. Accordingly, they should not lose billions of dollars due to “growth”. Nor are they or were they doing anything special to call themselves a “tech company”; there is nothing tech about the actual business model or what they actually sell to the end-user. It’s a glorified bank that predominantly deals with leasing out office space.

Of course, WeWork is now an “obvious” example because they very publicly almost went bankrupt and ousted their CEO toward the end of 2019. It was saved through an emergency loan from Softbank to effectively save their own investment.

General rule of thumb on valuation

We can use a general rule as a quick way to determine whether a company’s value makes sense.

Take a company’s market cap, divide by 10, and ask whether they’re going to be generating that in profit within 5 years.

Tesla’s market cap as the latter part of January 2019, is slightly north of $100 billion. Will it be making $10 billion in profits per year within five years? So far, its lost money every year, with those losses expanding as time has gone on since its founding in 2003.

Low rates have helped subsidize the growing market shares of various companies with profits having secondary to very little importance. This has been true for Tesla, WeWork, and ride-sharing companies such as Uber and Lyft. The market share game is broadly positive for consumers as it keeps inflation and inflation expectations low. But at some point, these businesses are not operationally viable unless they can make a profit.

The importance of diversification

Where in an environment where growth is low and interest rates are low, so capital is cheap. This makes the tech or “tech pretenders” some of the biggest market out-performers because a) they don’t necessarily depend on a high-growth economy to do well, and b) many of the unprofitable ones who haven’t shown they have viable business models need the low rates in order to keep their businesses going.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re great investments. A lot of it is speculative behavior that you probably don’t want to bet on either way, long or short.

And having concentrated exposure is highly risky, particularly in investments that are of dubious viability and are likely wildly overpriced.

Those who bought the Japanese equities bubble in the late-1980s are still underwater. Those who bought the NASDAQ bubble at its peak were underwater for 16 years. Innovation never stopped in the US tech sector, but it took a very long time for valuations to pick back up.

Seeing interest rates drop 6 percent – a tailwind to financial assets as their cash flows are discounted at a lower rate, boosting their prices – and $15 trillion in financial assets bought by global central banks also helped enormously. Otherwise investors could still underwater now over 20 years later.

Moreover, the notion of what companies are good and which are the most innovative changes frequently. Enron and Worldcom were considered the hottest and most innovative companies 20 years ago. Both were overpriced, both were fraudulent, and both ended up zeroing shareholders once the equity markets turned down and their problems were exposed.

The most valuable companies today are businesses that are entirely new within the past 20 or so years. Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft have large entrenched positions that should last a long time. Google rose to prominence through its ad platform delivered through its search engine. Facebook’s power is in its advertising algorithm generated from people sharing data about themselves. Amazon became a global hub for e-commerce. Apple is an older company, founded in the 1970s, but most of its value is through the iPhone (2007), which simply outdid its competitors in terms of design and functionality. Microsoft started as a hardware company, before shifting into software and the cloud.

To us, who or what will unseat these companies isn’t entirely clear. But this is how people thought about IBM and Walmart in the 1980s. IBM and Walmart are still large companies but they didn’t pivot successfully to a changing landscape in technological and retail trends and got left behind.

Another 20 years from now the landscape is likely to change as well as digital technologies evolve to artificial intelligence and its subsets (machine learning, deep learning), and how these can be commercially applied to create value.

Diversifying well

No matter how attractive something is, remember that all investments compete for investor dollars and the consensus is already discounted into their prices. Amazon is a high-growth company that makes a lot of money, but this is why its share price is as high as it is. It has to make good on those expectations to keep the share price at its level or to improve it.

Learning how to diversify a portfolio well is one of the best things you can do to improve your return for each unit of risk.

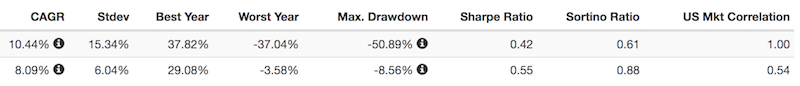

Compare the performance of the following portfolios:

– A “100 percent stocks” portfolio, and

– One that’s 20 percent stocks, 15 percent cash, 20 percent short-term bonds, 20 percent intermediate bonds, 15 percent long-term bonds, and 10 percent gold

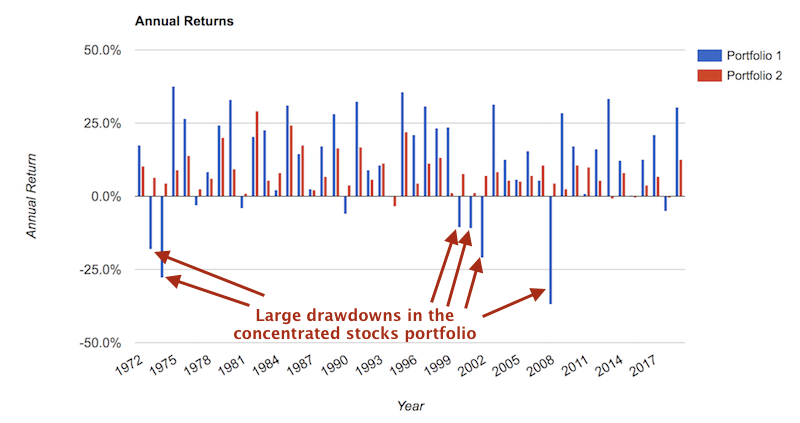

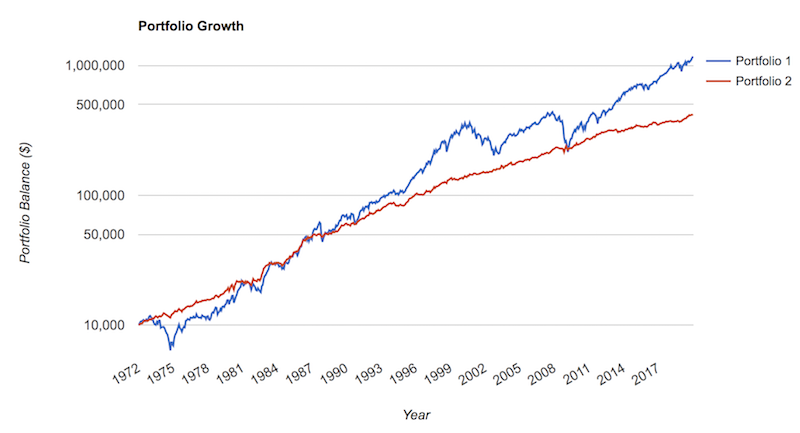

Your return relative to your risk is much better diversifying. Measures of risk to return, such as the Sharpe and Sortino ratios, are materially higher. (The stocks portfolio is in the top line and the diversified portfolio is in the bottom line.)

Moreover, your drawdowns are much milder. Note the much larger drawdowns associated with the concentrated 100 percent stocks portfolio.

This is the risk of having a concentrated portfolio and it happens at some point. No matter how many stocks you may own, it’s not a diversified portfolio because they have the same environmental bias. This would also be true if you owned only a bunch of corporate bonds or various commodities.

Your returns are much more linear in the well-diversified portfolio versus a concentrated stocks portfolio.

Most people overemphasize stocks in their portfolio.

After all, the public’s exposure to the financial markets is predominantly through the conduit of their domestic stock market and, within that, the most popular brands in particular.

When individual investors select securities, they’re most likely to pick brands they know and stocks that have done well in the recent past – even though this typically means that they’re more expensive investments rather than better ones.

People’s behavior buying stocks, and financial assets more broadly, differs heavily from their behavior when purchasing most anything else.

When the price of most goods goes down, that’s more likely to stimulate one’s demand for it rather than make it less attractive. When the price goes up, that usually limits demand. For most investors, the relationship is the polar opposite.

And some people have their own individual biases wherein they want their portfolios to be mostly or all bonds. Or they like gold. But that has the same issue. All broad financial asset classes and non-financial stores of wealth (e.g., gold, precious metals, commodities) have viability in a portfolio. But learning how to have balance and how to mix them well is key.

Now the main objection to this is – if you want to have more diversification you give up returns.

And that’s true. Bonds as a whole return less than stocks, so your search for diversification is constrained by giving up long-run returns.

However, as we discussed in a different article on portfolio construction, notably in the risk parity section, the key is to get each asset class to exhibit the same risk. This was not considered as part of the above comparison, as asset classes were simply taken as they come pre-packaged and blended into a solid mix to show the basic benefits of diversification.

In practice, we get assets to exhibit the same risk by leveraging them to make them equitable. For Treasuries, this is commonly done with either bond futures or through repo or basic cash financing. This is how all assets compete with each other on an equal footing. This is how bonds can compete with equities, which compete with real estate and private equity and all other asset classes.

Once you have gone through the process of making all asset classes exhibit approximately the same risk, you can diversify for all economic environments without forfeiting expected returns. Your search to have balance and diversification is no longer at odds with having to give up long-term returns.

Central banks won’t normalize interest rates

Central banks have increasingly come to terms with the fact that they can’t normalize interest rates. In other words, they can’t raise them much back up to a level that could help offset a downturn.

In the typical recession, it takes around 500bps of easing to get risk asset markets, and then the economy, to bottom. In the US, they’re at 155bps. In Europe and Japan, they’re at zero and negative not only at the front end of the curve, but out ten years or more in many of the most creditworthy countries.

Inflation rates are weak and central bankers look to be on hold until those run higher. In a November 2019 speech, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell stated, “It is essential that we at the Fed use our tools to make sure that we do not permit an unhealthy downward drift in inflation expectations and inflation.” In December 2019, he said, “In order to move rates up, I would want to see inflation that’s persistent and that’s significant.”

The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, PCEPI, has been under 2 percent for more than seven years now.

That means, for the time being, the normal reason why recessions happen – the central bank hiking rates to control inflation – won’t happen. That’s a good thing for asset prices.

Accordingly, rate hikes are unlikely if there’s not much in the way of inflation to rein in. In 2019, 49 central banks cut rates a total of 71 times.

Sometime in the intermediate future, the Fed is likely to officially change its policy. This will not be immediate, but it is likely to officially adopt some type of average inflation targeting.

The new policy change will be designed to do away with the notion that the public views the 2 percent inflation target as a ceiling, and not a symmetrical average. The Fed hiked rates nine times during the current cycle despite inflation running successively below target, reinforcing this belief.

Inflation expectations are important because they are likely to flow into actual inflation. This is due to such influences like how some worker salaries are moved up by a certain percentage each year. This filters into spending habits and pricing behavior and therefore inflation. Likewise, financial markets are forward looking. They price in future inflation expectations. This goes on to impact capital allocation decisions, which affects outcomes in the real economy.

Inflation is a key element of how asset prices move and is critical for traders to understand. (The other main element is growth.) Inflation has implications for the movement of interest rates and how that impacts the prices of financial assets through the present value effect.

The way cycles traditionally end is with central banks raising interest rates to fight inflation.

Inflation is not a problem and not likely to become a problem due to various structural reasons – i.e., high debt relative to income (depresses spending power if rates are raised), increasingly aging demographics, technological innovations that make relative pricing across retail channels easier, decreasing influence of unionized labor, and off-shoring and other forms of labor arbitrage activity.

This means that the cycle could go on for a while as long as interest rates remain low to keep it that way. In other words, nominal interest rates need to be kept below nominal growth rates to keep debt serviceability favorable.

Implications for currencies

With no attempt by the world’s major developed market central banks to raise interest rates, these currencies will remain range-bound relative to each other, and their values low in relative terms to something like gold.

Then you combine some level of steady simmering international conflict with China and Iran.

And take the effects of the ballooning US budget deficit and the intractable balance of payments deficit. These deficits require funding. That means the issuance of more bonds.

That brings up the question of how much demand there is for higher and higher amounts of US bonds and, accordingly, US dollars. A bond is simply a promise to deliver currency over a period of time.

Different types of buyers of these bonds have different motivations: For private sector domestic buyers, they care mostly about inflation – namely, what kind of real yield are they likely to get. But there aren’t enough buyers in the domestic private sector, so many of these have to be purchased from investors and institutions abroad. Foreign buyers have a different motivation – i.e., they care mostly about what happens with the currency.

If you buy a foreign bond that yields 2 percent (around what US Treasuries yield), it’s left unhedged in FX terms, and that currency drops 2 percent versus your domestic currency, then you’re left with a bond whose annual yield has just effectively been wiped out. If it depreciates more, the actual return of that bond is negative.

With the US needing to issue so many bonds, that’s not necessarily bad for bonds price (i.e., higher yields) due to supply. Any lack of the demand the Federal Reserve can simply buy.

But what it’s likely to become increasingly bearish for is the US dollar. The Fed will need to create the money to buy the bonds and that extra supply of dollar liquidity reduces the price.

And, naturally, the question is what will the dollar depreciate against?

The euro, the world’s second-top reserve currency, is not that attractive.

The EU has major challenges that don’t structurally apply to other economies. They don’t have a common fiscal policy. Italy and Spain regularly try to flout the EU budget rules entirely. Many EU countries have to share a uniform monetary policy because of the euro, which leaves rates too low in Germany (contributing to their surpluses) and too high in the periphery, where countries like Italy and Greece perpetually struggle to lift growth rates.

This bleeds into political movements, where the policies become more populist. The EU doesn’t have great unity within countries or between countries. There are major governance and sovereignty challenges.

The EU has structural issues that will come more to light when the economy turns down. Of all the major economies, Europe will be the most strained of all developed economies.

Then you take Japan. They have an intractable demographics problem and the most indebted society (as a percentage of output) at the sovereign level in modern history. Rates have to be kept low to keep debt servicing affordable. Holding the yen doesn’t earn you anything.

That goes for holding the yen in cash or as part of a bond. Even you hold a 40-year JPY bond – a promise to deliver yen currency to you over a 40-year period – you don’t even earn 50bps of yield per year. After taxes paid on the interest and inflation, your return is negative.

So, not many people think the yen is very attractive to hold. Many short it to fund the purchase of higher yielding assets, in what’s commonly known as the carry trade.

The US dollar is still far and away the world’s reserve currency in comparison to euro, the next most widely held and used currency.

Just in terms of the general statistics:

– FX reserves: USD = 62 percent; EUR = 20 percent

– International debt: USD = 61 percent; EUR = 23 percent

– Global import invoicing: USD = 56 percent; EUR = 35 percent

– FX turnover: USD = 43 percent; EUR = 15 percent

– Global payments: USD = 39 percent; EUR = 34 percent

In global payments, the euro is comparable to the US dollar. But it is very far off in terms of how the big institutional money and central banks treat it. On that front, the US dollar is three times more commonly held in these types of portfolios.

China is a rising power and the world’s second-largest economy, but it’s currency is nowhere near the level of being held as a major reserve currency. As an emerging market with its own host of issues – in terms of its authoritarian government, limited private property rights (in comparison to a country like the US), its need to develop better rule of law, its volatile and still under-developed financial markets, its substandard regulatory oversight – the yuan has a long way to go.

But the US’s own fiscal challenges give the dollar long-term issues. The US losing its hold as the world’s top reserve currency is within the range of possibilities thinking many years out (i.e., a decade or more).

Fewer foreign entities want to hold dollars. At the least, they aren’t that inclined to add to their existing stock. This includes China, Russia, Iran, and others.

But at the same time, central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and institutional funds still need to hold something. With all reserve currencies at zero, negative, or near-zero yields, they all present issues in the form of a lack of return. Emerging markets have higher yields but have accompanying risks in various forms.

Gold as an alternative (in a smaller amount)

That means you can probably expect something like gold to stand out.

Gold has its own set of issues that makes it an imperfect store of wealth. It can’t take in large amounts of inflows from financial assets. There are still less than 2 billion ounces in global gold reserves above a certain level of purity. That means the global gold market is valued at a bit less than $3 trillion, compared to over $100 trillion in equities and about $300 trillion in debt securities. (That excludes the notional quadrillions in financial derivatives.)

Gold’s price is largely the inverse of money. As developed markets face their own indebtedness issues compounded by interest rate policies that are maxed out, this causes policymakers to continue to print more money to kick the can down the road. Namely, they are simply exchanging one IOU for another. They aren’t getting at the things that matter the most over the long-run, like improving productivity.

When rates are low and secondary forms of monetary policy, such as asset buying, also become ineffective because the risk and liquidity premiums have already largely been closed, this leads to new policies that continue to deprecate currency.

These can include the central bank giving money directly to savers and paying for deficits directly. Some central banks will attempt to depreciate their currencies, but this is heavily zero-sum because other central banks are likely to respond in-kind to avoid being put at a competitive disadvantage. This brings along with it more challenging political situations.

Gold is simply an alternative currency to fiat currencies, a system that’s been the standard since the breakup of the Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971. The behavior of gold is simply that of an alternate type of cash that has diversification merit. Generally something above 5 percent of a portfolio, but usually below 10 percent is a good type of allocation. It shouldn’t be overemphasized because it’s simply another form of cash.

But when everything else is frothy – stocks are very high, bonds are priced so high that their yields are zero, near-zero, or below zero – that makes alternative stores of wealth more attractive in relation.

Conclusion

In the main reserve currency countries – US, EU, Japan – cash yields zero or close to zero and bonds are also zero, negative, or close to zero as well. The US still has some room in its curve to stimulate asset prices, some 150-220bps, but they’re really in the same bucket as Europe and Japan because of how close they are.

That means investors are increasingly pushed out of cash and bonds and into riskier assets like equities and private investments like real estate, private equity, specialty lending, and venture capital. All of these compete for investor dollars. Their future returns get bid down as well as their prices go up, contributing to general froth in the stock market. Their forward returns don’t look that great in comparison to their risk.

To navigate this type of environment, it’s critical to have balance in your portfolio.

If you look at everything, nothing is particularly attractive, at least in relation to the risk you’re taking on.

Having a strategic asset allocation mix that balances asset well to get to a neutral position where you’re not too dependent on any type of environment playing out is key. As opposed to tactical asset selection where you’re jumping in and out trying to bet on what’s going to be good and bad. That’s not an easy thing to do even for professionals with large budgets for hiring investment professionals and acquiring the best data and technology available to them.

Most people are biased to be long their home equities markets. This builds a lot of environmental bias into a portfolio where the health of most people’s portfolios is dependent on the stock market holding up. When you have balance from having a strategic asset allocation mix, the risk shifts from “I hope the stock market will do well” to will this allocation outperform cash?

You can feel pretty good about taking on this risk.

In capitalist economies, cash has to outperform financial assets over time or the system doesn’t work. People who have good uses for cash will borrow it to create and invent things. Only for short periods of time does cash outperform financial assets – periods like, for example, 1982, 1994, and 2018 when a balanced portfolio didn’t do as well and neither did anything.

When the central bank recognized the need to ease following, the balanced portfolio had outsized gains the following year.