How to Leverage Cash Yields

Even with the Federal Reserve cutting the fed funds rate – which is the predominant feeder into cash rates in the US economy – cash is still one of the best returning financial assets. Treasury bonds return even less or about the equivalent. Stocks do not provide much extra in compensation relative to their volatility and risk (only about 4.0 percent above that of cash). This article will discuss how it’s possible to leverage cash yields.

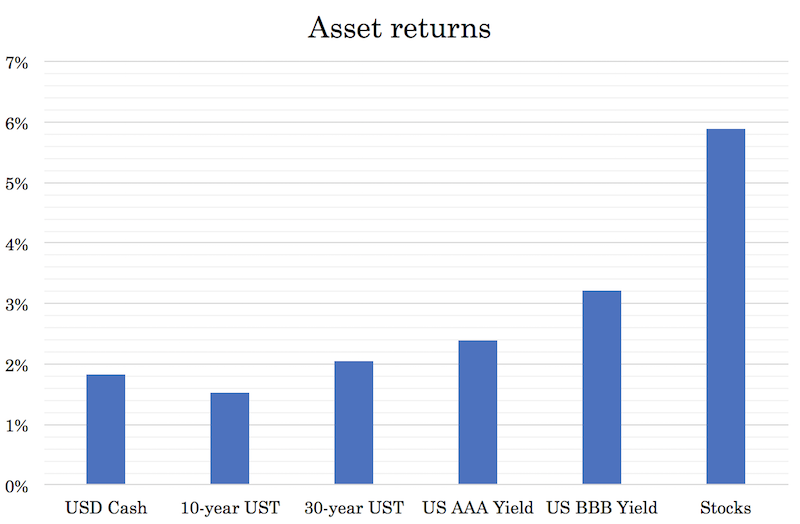

Cash yields a return of just under 2 percent in the US. Bonds yield a bit less, the same, or a bit more depending on their type (based on amount of credit and duration risk), and stocks look reasonably priced relative to bonds and okay relative to cash (a long-term Sharpe ratio, or excess returns over excess risks, of 0.25-0.30, which is typical).

The chart below shows the relative differences between different types of USD-based assets.

Leveraging this cash return, given its relative risk profile, can be valuable if done well.

The value of cash

At various points in time, you will need to recognize that the cost of being involved in a market will be higher than not being involved. In this case, being in cash or cash-like securities can prevent losses and maybe even give you some type of positive return.

Being in cash allows for the ability to take advantage of opportunities that come along that you wouldn’t be able to otherwise. Sitting on a sufficient cushion of cash (say 10 percent of the total equity value of your account) will also go a long way toward ensuring that margin deficits never become an issue.

The issue with cash

Cash is typically taken as the three-month rate on domestic sovereign debt. It’s safe, has almost no volatility, and gives you a rate you can reliably make over the next quarter.

What this rate is depends on where you go in the world.

In the US, cash will yield around 1.7 percent. In Germany, it’s minus-0.60 percent; in Switzerland, minus-0.94 percent; in the UK, 0.70 percent; in India, 5.2 percent.

Cash, as a whole, is usually the worst asset you can have from a return perspective. Cash is something you typically borrow to produce a higher return elsewhere. That’s how the capitalist system works. In other words, if you are a trader, investor, business person, homeowner, asset owner in general, you are typically short cash.

You want to hold some cash, but not too much. Its risk might be low, but after inflation and taxes, it yields probably nothing or even negatively (as it does in developed markets).

So, to have cash work as an investment, you need to figure out to leverage cash yields in some form to make its return passable while still keeping its risk under control.

Leverage cash yields: markets and trade structures

We’ll go through these opportunities one by one. This will be centered toward US traders, though can also be applicable toward the cash markets in other currencies.

1) Buying US Treasury cash bonds on leverage

One option is to buy US Treasury cash bonds through your broker. “Cash bonds” means you are buying the underlying securities. Some broker-dealers, such an Interactive Brokers, have institutional grade platforms for transacting in the Treasury cash bond market.

This method is risky because it has to be managed properly.

The general method is to buy Treasuries on leverage – collateral requirements are only 1-10 percent depending on the bond’s maturity – then swap out the negative USD balance (incurred from buying the bonds on leverage) for a foreign cheap currency (e.g., JPY, CHF, EUR) by buying USD against one of those currencies.

The net effect is that you will own a pile of Treasury bonds giving you some type of yield, and short a cheap funding currency. In other words, you’re shorting the cheap currency to be long the higher yielding US Treasury bonds.

The cost of USD leverage is typically the effective fed funds rate plus 150bps for lower sums of borrowing (under $100k). That means you’d be borrowing at 330-340bps based on where the rate is at the time of writing.

No Treasury bond gives you that type of yield, so you’d actually lose money investing in US Treasuries on leverage by keeping your borrowing in dollars.

Therefore, the rationale is to borrow in a cheaper currency.

For example, let’s say you have a cash balance of $100k before buying the Treasury cash bonds. You buy $200k worth of Treasury bonds. After, your USD cash balance is -$100k.

To cover that USD cash deficit, you could buy $100k in USD/JPY (or a bit more to have a bit of a cushion to ensure no interest charges occur if the balance were to go negative based on fluctuations in your portfolio value).

This way, you’d incur interest on the yen instead of the dollar because you’d now be short JPY. Then the trade structure is designed to profit off that spread between the yen interest and US Treasuries.

For this trade to work you need to believe that the appreciation and interest received from the US Treasuries is enough to offset the interest paid on the yen (or euro or franc or whatever cheap currency is being borrowed in).

The longer the duration of the bonds, the greater their volatility and the more you are making a concentrated bet on interest rates.

On Interactive Brokers, for every $100k borrowed (in approximate USD equivalence) in one of the cheap zero-interest rate currencies they charge 1.5 percent. This is expensive, but among the best available among online brokers. For $100k-$1mm borrowed, the cost is 1 percent. For every dollar equivalent past $1mm, it’s 0.5 percent, which starts to approach the rates you might get if you were primed with an investment bank.

If you borrowed at 150bps, and bought short-term USTs at 1.7 percent, for each turn of leverage you would profit 20bps (170-150). If you were borrowing at 100bps, then 70bps (170-100).

But this is not it. You need to hedge your foreign currency exposure. If you do not, you are basically making a leveraged forex trade – plus the duration risk from the bonds – so the risks are diverse and your expected returns outcome would have a very wide range.

For example, if you are leveraged 4x, for each 1 percent depreciation in the USD against the currency or currencies you borrow in, that would be a 4% hit to your portfolio. When you borrow in a currency, it is a short bet against it.

When you are borrowing in higher quantities, it develops into a concentrated short bet. The movement of your portfolio is therefore not primarily dictated by what the stocks, bonds, and other assets do, but rather from fluctuations in the exchange rate. For the same reason, this is why when countries borrow in foreign currencies there is a huge outlying risk (e.g., Argentina, Turkey).

There are ways you can hedge it.

You can diversify your liability currencies, taking short positions in multiple cheap funding currencies. But this only mitigates your risk to an extent

You can use futures contracts. If you are short $117k worth of yen, buying one JPY futures contract (implicitly a long JPY/USD position), will neutralize your position.

Or you can use a type of hedging strategy, such as a collar or risk reversal.

For risk reversals, you can buy a JPY call and finance the option by selling a JPY put. Risk reversals are a common way of managing foreign FX liabilities because if the currency you’re borrowing in were to depreciate you could help offset the loss through the appreciation in the options. And since you’re both buying and selling options, you don’t have to fork over too much capital, though it still is likely to cost some collateral on net.

2) Treasury futures

Treasury futures allow traders to get leveraged exposure to the US Treasuries market to an even greater extent than what they can achieve in the cash bond market. Some traders use futures contracts – and the corresponding options market – as a way to hedge interest rate exposure in their portfolios.

At current market prices, buying ZT (2-year Treasury futures) can get you access to $216k worth of 2-year USTs with a collateral requirement of just $640. That means for every $1 you place on margin, you get access to $337.5 worth of 2-year Treasuries. In the cash bond market, the outlay would be something closer to $1 for $30 to $50 worth of 2-years.

The relationship between the cash bond market and futures market for rates and credit is a bit more complicated than simply trading cash bonds. This is because each futures contract has optionality embedded in it. This means the seller can deliver one of several viable securities, not always giving you a clear-cut idea from the outset as to what your expected yield is.

There are entire books written on this subject.

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) has a 23-page white paper on Treasury futures.

It also has an analytics tool that can be found here.

A more in-depth guide on Treasury bond futures can be found here that’s largely considered the most influential guide on the subject.

The upside to Treasury futures is it involves no foreign currency borrowing and therefore no FX risk, like you’d have to incur and manage above.

How do I get the yield on Treasury futures?

One of the more common questions people ask with respect to the Treasury futures market is – how do I get the yield of the bond?

The answer is that yield is already implicitly embedded in the price of the contract. Treasury futures have no coupons. If the cash bonds included the coupon and the futures contract simply represented the price movement, the owners of the cash bonds would have a big advantage over the owners of the futures contracts. One could simply buy the cash bonds and short the corresponding futures contract and lock in a risk-free return.

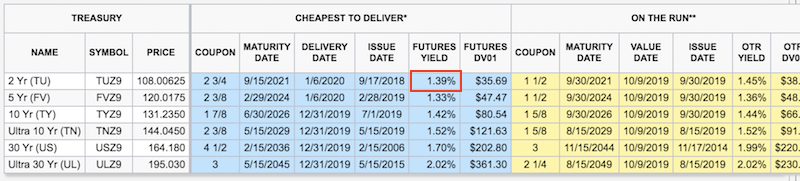

However, this doesn’t really exist in practice because traders arbitrage out this difference. In other words, locking in some type of positive yield without price risk is a popular enough strategy that it yields very little. In the analytics tool on the CME website, the effective yield of the futures contract is displayed for all maturities.

(Source: CME Treasury Analytics)

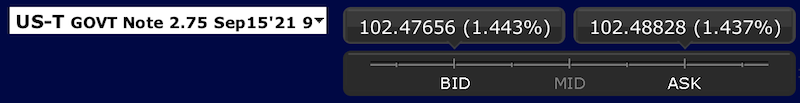

If we look at the 2-year Treasury yield, which is based on the Sept-15-2021 maturity, it is currently 1.39 percent in the futures market.

In the cash bond market, it yields 1.44 percent.

This differential of 0.05 percent means that most of it is arbed out.

3) Treasury swap rates and other interest rate market products (e.g. LIBOR, SOFR, eurodollars, fed funds)

These are derivative contracts. The 2-year US Treasury future goes by the symbol ZT; the corresponding swap is T1U.

Swap rates normally trade at a slight premium to the cash bonds due to the additional credit risk associated with the swap contract itself, though this isn’t true at the highest durations (30-yr US Treasuries yield more than the swap rate). Why this inversion exists between cash bond yields and the swap rates will be covered in a future article.

You can also trade cash market products, such as LIBOR rates, SOFR (LIBOR replacement scheduled for December 2021), eurodollars, and fed funds. These products allow you to bet on their forward rates.

4) FX, FX futures / forwards / swaps / options

Bonds are simply fiat currency flows that are spread over a longer duration.

The spot FX market is fundamentally a cash market. Instead of a bond giving you interest spread out over time at fixed intervals, the spot FX market gives you daily interest based on the cash positions you hold. Depending on what currencies you hold long and hold short, that will normally equate to some amount of net interest gained or net interest paid.

Gaining carry on USD involves being long the dollar against a cheaper currency. A cheaper currency means one that pays less overnight interest, such that there’s a positive spread.

At the current point in time, the USD is one of the few developed market currencies that provides any material amount of nominal yield above zero at the prevailing spot rates.

Most brokers, unfortunately, don’t give you good rates. So, trading FX for carry will depend heavily on what broker can provide a reasonable amount of interest. For instance, a long USD/CHF position should normally net you around 2.6 percent of carry based on the rate differential – 170bps on USD and negative-90bps on CHF. Leveraging this position could get you even higher yield. However, with most brokers you would earn basically nothing in net interest.

There’s also, of course, the factor of risk. Your return will be impacted by spot moves in the currency pair. If the CHF gains ~2.6 percent against the USD, that effectively wipes out your annual carry.

Carry trades, more generally, tend to be like synthetic short gamma positions. They typically produce slow steady returns during tranquil times and wipe out your carry during more volatile, turbulent times in the market.

Because cheap currencies are funding currencies, with traders looking to borrow inexpensively to chase the returns of higher-risk assets, these positions are unwound during risk-off events. Whenever a short position is covered, that causes a rebound in its price. Accordingly, currencies like JPY and CHF tend to be negatively correlated to the global credit cycle and global equities. There are also macroeconomic reasons behind the “safe haven” status of these currencies. (Japan and Switzerland are creditor nations without dollar debt problems.)

You can also do FX trading outside of spot transactions. Brokers that have options on FX futures allows you to do this. Other strategies include shorting a cheap currency on the spot market and going long the carry currency in deliverable swaps. Or shorting non-deliverable swaps in the cheap currency and going long the carry currency.

FX futures take into account carry for the same reason Treasury futures do. Buying a JPY futures contract will give you exposure to about $117k worth of yen (borrowed against USD) for a collateral outlay of just $3,162 (2-3 percent margin).

There are a lot of opportunities; what’s best to do is a matter of what kind of products are available to you, what your financing terms are, and what you feel most comfortable doing.

A note on leveraging cash yields with flat yield curves

Most yield curves throughout the developed world are inverted in parts, flat, or close to being flat.

As rates on the short-end rise to a level of those on the long-end, hedging out currency risks can make many types of trades unprofitable. Many financial intermediaries depend on the relationship between borrowing short and lending long.

When the Fed hiked interest rates in 2017 and 2018, the short end of the curve rose while the back end of the curve remained relatively anchored. For EUR and JPY based investors, the cost of holding USD increased, and even to the point that made US Treasury yields negative for these investors. This made foreign flows into USD debt less reliable. Finding foreign buyers for domestic debt becomes more difficult when the spread between short-end rates and long-end rates converge.

As covered in a different article, for many non-US investors in developed markets (i.e., EU, Japan), US Treasuries actually yield negatively if they wish to currency hedge their investments.

Banks, life insurers, pension funds, and other institutions commonly use 3-month cross-currency basis swaps to hedge exposure, defined as 3-mo USD LIBOR vs. the 3-mo rate in the other currency. The lower the swap rate the higher the hedging costs on a cross-currency investment.

A Japanese life insurer might want to buy Treasuries, but after hedging the FX exposure, the actual yield is now negative. Therefore, the trade is uneconomical.

That’s why a lot of Japanese investors are favoring their own debt relative to US Treasuries.

So, they need to either:

1) look at higher-yielding US assets (corporate bonds, equities, CLOs, etc.),

2) look at assets in other countries, or

3) don’t hedge at all or only partially hedge (or become more creative with the hedging process) and take a big risk on currency fluctuations (with a 2-3 percent adverse fluctuation in the USD against the domestic currency wiping out the yield entirely)

Conclusion

Cash is both a good thing and a bad thing. You should have some quantity to give you safety and flexibility. But you don’t want to have too large a quantity such that your returns don’t amount to much or anything. Or, in developed markets these days, cash will yield negatively in both nominal and real terms in many countries.

However, there are still ways to leverage cash yields to generate returns that are well in excess of the nominal rate on cash. As you might expect, there is risk involved because leverage will need to be employed. These include:

– Leveraged bets on cash bonds (while hedging out FX risk)

– Through Treasury futures (which are really bets on interest rate movements)

– Interest rate contracts, swaps

– Spot FX market, by leveraging a cash position against a cheaper funding currency

– FX futures, options, forwards

With that said, never try a new market or trade structure without fully understanding what you are trading. Always paper trade or try out in a demo account first to understand its behavior and risks before putting it on with real money.