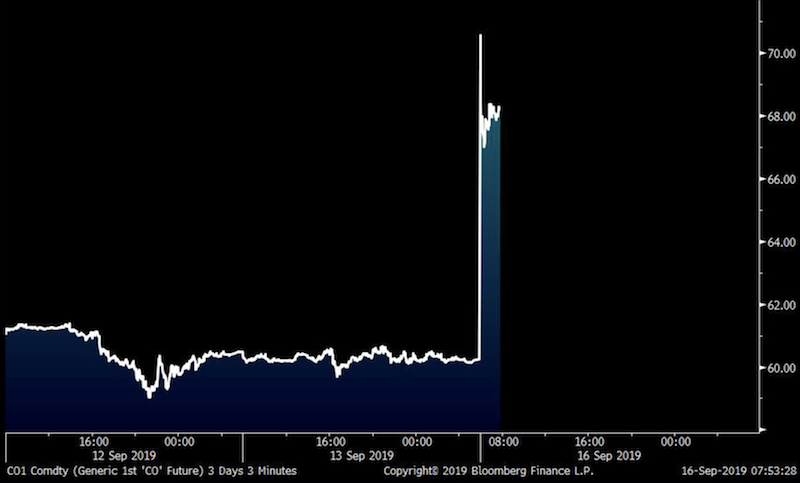

Lessons from Oil’s Largest Spike in 28 Years

All market watchers know the details by this point. Drone strikes on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq facilities sent crude oil prices flying 10 percent or more depending on the type of crude. Brent crude, shown above, is more susceptible to a Saudi outage than WTI.

It was the largest daily gain in 28 years, back when the beginning of the Gulf War sent prices moving.

Geopolitical tensions in the Mideast are always with us and a form of risk that’s hard to quantify. The situation in Iran can always deteriorate and various oil-producing nations, Saudi Arabia in particular, are susceptible to attacks on their oil infrastructure.

Most traders tend to be focused on stocks and are concerned about how to hedge against downside equity risk (because most people are long, often in a leveraged way). However, instead of considering basic hedges like puts against stock positions, one could make a case for hedging with long-dated out-of-the-money oil calls.

If there’s ever a supply disruption or the outbreak of a conflict that could impact supply lines, that’s a materially bullish event for oil.

What happens if Saudi Arabia and/or its allies decide to retaliate?

Markets can move more than most think. 10 percent in crude oil is a large move, but it’s done over 30 percent in a day before. Anything can happen. It’s the probabilities that matter.

Things can happen that aren’t priced into the distribution. It’s why being short gamma – i.e., selling options, which can have theoretically unlimited downside – can be so dangerous.

While markets are highly sensitive to the US-China trade conflict, the move in crude emphasizes the reality that geopolitical risk is higher than most might imagine. The new premium that’s been fed into the oil market will also remain elevated for some time even if the raw supply and demand economics aren’t altered much.

With that said, there are broader trading lessons to be learned from this event.

Let’s go through them:

Don’t be short gamma*

Short gamma, broadly speaking, means selling (sometimes called “writing”) options.

First, with a caveat:

*If you must be short gamma, be willing to purchase the stipulated amount at the stipulated price. This is what selling an option, if it lands in-the-money (ITM), will require you to do. Or, better yet, be covered by not selling options naked.

Selling out-of-the-money (OTM) options is a bet that has a relatively high probability of working out because the price needs to move enough in a certain direction for you to lose the wager. But it’s like picking up dimes in front of a steamroller. It tends to produce a little bit of profit for a while. Then when a dislocation comes you really blow a hole in your portfolio, losing many multiples of the premium you expected to receive.

Many people use them because it seems like an easy way to make money. But anybody who is short gamma in any frequency will eventually get burned badly.

With that said, options premium can occasionally be a useful source of return if employed wisely. For example, if implied volatility is higher than what realized volatility is likely to be and you are willing to buy or sell at the price and quantity stipulated by the options contract, then it can be an opportunity. Better yet, if your position is covered, you aren’t exposed to the big downside risks that normally accompany being short gamma.

Just note that when people blow up their portfolios, it’s typically due to the uneducated use of leverage or by irresponsibly selling options. It should be used very selectively or avoided altogether.

Carry trades can also be considered forms of synthetic gamma trades. Being long the Turkish lira (TRY) against the Japanese yen (JPY) seems good in theory when one currency yields 16 percent or more and the other yields slightly negatively, but this return comes with very high risk. Carry trades, like most short gamma trades, tend to produce smaller bits of income for a while before the dislocation comes and wipes out everything (and often more than everything).

Some FX carry trades lost years’ worth of gains in a few weeks in 2008.

Moreover, people who had a lot of success shorting equity volatility throughout 2017 lost a massive amount once February 2018 rolled around.

Cap your downside

Trading is fundamentally about accurately assessing risk versus reward and keeping downside manageable. If you get the relative probabilities right over time you’re likely to get ahead.

Whatever your approach or markets you trade, you need to find a way of systematically getting the odds in your favor. If not, you’re almost guaranteed to lose.

The only true way to cap your downside is by being long options (“long gamma”). You know exactly how much you can lose unlike when you have a position in an underlying instrument or are short gamma.

When there’s a dislocation in a market, a stop-loss is not going to help you. Markets will gap. When Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities were attacked on Saturday, a day when the market wasn’t open, there was nothing you could do if you were short oil or wanted to protect your portfolio in any way.

If you were short WTI crude oil and had a stop-loss at $55.00, your stop-loss would have gotten you out at the next available price, which was Sunday night and well above $60. If you were in CL futures – the most common way to directly trade WTI crude oil – you would have gotten out of the trade, but not before losing $7,000+ per contract. If you had been short through a put option, the value of that put would now be very low, but your loss would probably be small in comparison. Unless it was a deeply ITM option, in which case it would act much like the underlying commodity.

Don’t leave positions on inadvertently

Never make an inadvertent bet.

As mentioned above, if you don’t have a way to systematically skew the odds in your favor, you won’t win in the markets over the long-run. Never keep positions on inadvertently and never bet on something that you’re not deeply knowledge about and have some sort of edge on.

Also, don’t forget to close out positions that you may get assigned through options.

For instance, if you have an options contract that expires at the end of the week and it’s ITM, you need to prepare for how to handle that because it’s likely you’ll get assigned. If you have no desire or intention to hold the asset beyond the option’s time period, you should close out the position.

You can do this by either selling the option or by covering it by taking a position in the underlying. Selling an option is often not the best choice because the spreads are wider than they are in the underlying market. That means you’ll lose some amount of money because of the spread. Options markets tend to be illiquid relative to markets in the underlying.

Example

Let’s say you are long 56 CL puts (WTI crude oil).

It’s Friday and these are ITM.

That means if these stay ITM you will be assigned CL short.

If you leave that on during the weekend and something happens, then you’ll face a huge loss that you can’t control.

In order to control for this, to ensure you won’t get assigned, you can buy CL contracts in the amount equal to the number of long puts that you own. This will neutralize your position and would get you flat heading into the weekend.

Always keep enough capital cushion in your account

If you are running low on collateral, it can force you into doing things that you don’t want to do.

You may be liquidated when positions go against you and you may need to sell off positions manually that you might have high conviction on. You also won’t be nimble enough to get into good opportunities when they present themselves because you happen to be capital constrained.

It seems like common sense to keep this cushion available, but some like to run their collateral (also known as “excess liquidity”) down very low to ensure they’re taking advantage of their entire account size.

Resist the temptation and always try to have about a 10% buffer room. Having more than that is fine, especially if you don’t have great trade ideas.

It will go a long way toward keeping you out of any margin call related issues and allow you to take advantage of opportunities as they come.

Don’t underestimate the probability of fat-tail events

Markets can move more than most would expect.

Implied volatilities are based on historical volatilities. This is good in theory as historical volatility reflects what the asset is like. But at the same time, things can happen that are outside the distribution of expectations.

Moreover, many risk management models are based on the normal distribution. The problem is that the normal distribution has relatively thin tails. Financial market variables tend to be fat-tailed. Therefore, if you’re using the normal distribution for risk management or forecasting, you’re likely to be materially underestimating the odds of low likelihood events.

What some market commenters might describe as a “five sigma” event – i.e., five standard deviations from the mean, or something with only a supposed 0.0000003% chance of happening – is most likely not a “five sigma” event at all. It’s that the distribution used to model the probabilities is flawed.

Long-Term Capital Management, which in the 1990s was at the forefront of investing, thought it had a 1 in 6 billion chance of its portfolio blowing up. It looked at historical data to estimate future risk. But financial market history is full of theoretically low probability events that indeed transpired.

For all the intellectual capital inside LTCM, they failed to consider their own liquidity premium. Namely, there’s a correlation among positions for no other reason than the fact that they held them within their own portfolio.

The LTCM episode reminded market participants that risk-free arbitrage trades don’t truly exist. There is always some form of risk. Moreover, the arbitrage trades they were trying to take advantage of had very little yield on an unleveraged basis. So, they had to leverage them up significantly to produce the desired levels of returns. But at the sizes they were trading, this magnified the risks in a non-linear way.

Normally leverage is a double-edged sword that improves risks and returns linearly. LTCM was managing $5 billion in assets, which, through leverage, became over $1 trillion notionally. In other words, they were leveraged 200x.

This put them at a massive risk to small fluctuations in the financing fees given to them by their lenders and also subjected them to the whims of market liquidity.

LTCM’s scope and influence became so large that it’s impending failure from over-leveraging and flawed risk management modeling endangered the global financial system in the late 1990s. Markets also sniffed out their situation and traded against them. This squeezed LTCM further.

While this may not pertain to many, you never want to be such a big part of your markets that somebody could squeeze you. This is why investment managers will need to cap their size if they are active in nature (not passive, or simply emulating market returns). Not only do transaction costs increase in a non-linear way, but past a certain point of capitalization you can be such a large influence on the markets you trade that you can get squeezed if somebody decides to trade against you.

A drone strike on Saudi crude oil facilities is one of these multi-sigma, fat-tail events that occurs very rarely but is always a risk. Nobody can predict it and nobody can really hedge their portfolios against something like that entirely.

If something has never happened before the only thing you can do to hedge yourself completely is to cut off the left-tail risk entirely. Being long gamma (owning options) can help you accomplish this.

Conclusion

In trading, it will seem as if you’re constantly relearning the same lessons. You might make a lot of the same mistakes, but hopefully they become less frequent and more trivial.

The move in oil was a wakeup call not just for oil traders, but for all traders to not underestimate the potential for markets to move in a way they don’t expect.

Some principles to keep in mind:

Don’t be short gamma

If you do, at least make sure that you’re covered (in which case, you’re not short gamma) or it’s a position you really believe in. Don’t be short gamma just to try to make a quick buck.

Cap your downside

To cap your downside, stop-losses won’t work in illiquid markets or when prices gap, as they just did in oil. If you had been long options, you would have been able to cut off the left-tail risk entirely. It would have been up to the counterparty who had sold you the option to manage that risk. (That’s what you effectively pay for in the premium.)

Don’t leave positions on inadvertently

Never make an inadvertent bet. Make sure every position you have on has a clear rationale behind it. The market is always an objective indicator of your performance. If something goes against you, saying it’s because the market is irrational or because you’re unlucky is not helpful. Things can always happen in whatever market you’re in and you need to be prepared. It’s never a good idea for any trader to blame something or someone else for any trading mistakes that occur.

Always keep enough capital cushion in your account

It’s tempting to use all your collateral for active positions. But try to have a 10% cushion or more. This keeps margin calls away and allows you to take advantage of any opportunities that come your way.

Don’t discount the probability of fat-tail events

In trading and in business, things will always happen. Only bet on the things you feel most confident about and you have deep knowledge in. Balance your risks well. Never have too much in any given position or any given theme. Watch your correlations. Have a variety of preferably uncorrelated positions. Reduce your risk to the lowest amount possible (buying options is a good way) that keep the big upside while reducing the potential downside.