Argentina’s Debt Restructuring

In a recent article, we took a look at the issues confronting the Argentinian economy. For those who trade emerging market currencies (“EM FX”), it’s important to understand the fundamentals of what makes a currency move and idiosyncrasies governing these currencies.

Unlike when you’re trading a G-7 currency pair, you don’t regularly have to worry about devaluations, capital controls, capital flight, surprise multi-percentage point moves in interest rates, strong political upheaval, and other matters that suddenly influence a currency.

The seeds of Argentina’s current debt problem

The current seeds of Argentina’s present debt problem were arguably sown back in 2017. That year a rise in imports caused their current account deficit to blow out to 5 percent of domestic GDP.

Argentina, however, does not export enough products and services to cover that. That caused its current account deficit to expand. With a current account deficit, this means Argentina needed to turn to the debt markets to fund this imbalance.

Given that Argentina has a small banking system and low levels of domestic savings, it heavily prefers to borrow externally in foreign currency (USD and to a lesser extent EUR).

The danger with borrowing in a foreign currency is that if the domestic currency declines, that makes the debt more expensive and harder to service. It effectively serves as an interest rate increase.

When debt is denominated in a foreign currency, it can’t be managed it in all the usual ways like it would be if it’s denominated in one’s own domestic currency. This debt management process includes having the autonomy to change the rates, re-profile the maturities, and/or alter whose balance sheet it’s on.

Maturities were shortened earlier this year to reduce their costs. But that led to servicing costs being brought forward. That included $3.3 billion due in June, $3.7 billion in July, and $2.6 billion in August. It now includes $4.5 billion in September (the month this article is being written), $3.1 billion in October, $1.3 billion in November, and $600 million in December. It has $38 billion in debt due next year, both foreign exchange debt and peso (domestic currency) debt.

To service these amounts, Argentina needs a substantial restructuring or re-profiling.

(A debt re-profiling refers to the process of rescheduling maturities, but no write-offs or markdowns as is typically the case in terms of debt restructurings.)

Macri’s Legacy

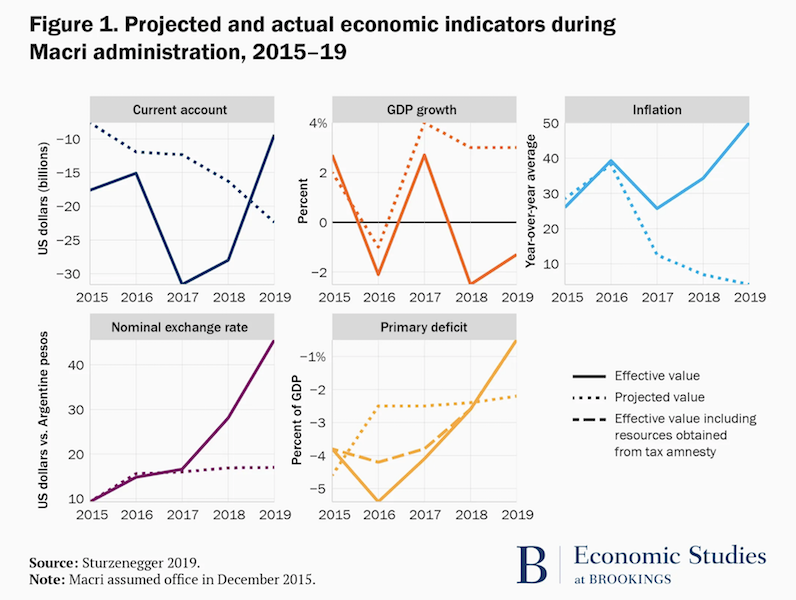

Argentina President Mauricio Macri brought confidence upon his election that his pro-market agenda would make the country’s debt manageable. A country with a culture embedded in trade protectionism, mercantilism, populism, and broader state control of the economy had seemingly decided to begin detaching itself from longstanding Peronist control.

Macri took the step of moving the peso off its peg once his term started. This brought a devaluation, though the currency stabilized soon thereafter. However, this brought credit risks because the debt and broader economy is more susceptible to a shock in the exchange rate more than any other broad economic force (e.g., volatility in output, volatility in interest rates).

Reaching a settlement with creditors on its 2001 default also allowed the government to tap the international markets for capital. In addition, this allowed its central bank to begin building reserves.

An inflation targeting program instituted in March 2016 worked in helping control and draw down inflation, which had remained stubbornly high (25%+ annual rate) for years. By the end of 2017, inflation targeting had gone roughly according to plan, drawing it down to a 17% annualized rate, with another 200-300bps expected to be run off in 2018. However, the program was ended without warning in 2018.

After the 2017 midterms, in which Macri’s governing coalition performed well, the government believed it had more leash to operate according to its desired ideological stance.

It then altered course on key policy decisions. The inflation target was raised and interest rates were lowered, which is inherently stimulative. This contradicted the central bank’s ongoing program, which led to interpretations that its independence from Macri’s regime was being undermined.

Moreover, at the same time, US rates were in the middle of a tightening cycle, in which the Federal Reserve intended to (and did) raise rates four times in 2018. The extra yield on US cash and other short-term US assets facilitated USD inflows. Argentina’s economy was impacted by a drought that limited its agricultural exports. The growing deficit in its balance of payments caused the peso to devalue rapidly given the funding shortfall. This caused its debt servicing costs, heavily denominated in foreign currency, to compound.

Macri turned to the IMF for relief. The IMF responded with a $57 billion lending assistance program in exchange for structural reforms to the economy.

Traditionally the IMF will require collateral in exchange for the loan in addition to some set of changes specific to improving the country’s conditions.

These can include the following:

1. Cutting spending and expenditures, balancing budgets, reducing funding gaps, and other austerity measures

2. Finding ways to enhance economic output, such as encouraging resource extraction to build a larger export base

3. Opening up trade through the removal of tariffs and other import and export restrictions

4. Decrease inefficiencies and waste via increased privatization of the economy through incentives (e.g., lower business taxes, lower regulations) and divestment of state-owned enterprises

5. Enhancement of private property rights

6. Improve governance procedures to crackdown on corruption

7. Build or better open up domestic capital markets to assist in foreign direct investment inflows; improve investor rights

8. Remove wage controls and/or price controls

9. Suggestions to currency policy (e.g., devaluation is stimulative, though can exacerbate debt problems in countries with a high amount of foreign exchange debt)

10. Suggestions to monetary policy depending on expected growth and inflation trends, as well as the country’s individual financial stability situation

—

In exchange for the IMF’s $57 billion loan, Macri agreed to run a more contractive fiscal and monetary policy stance to get public spending and inflation under control. Moreover, it would better embody the notion that central bank policy is independent from the Macri regime’s influence. Public investment was curtailed, export taxes were implemented, and the country’s stabilization fund was drawn down.

(A stabilization fund is typically used as a type of “countercyclical buffer” to protect against economic vagaries over which a country largely can’t control, such as the price of an important commodity.)

Nonetheless, in August 2019, Macri’s political support had dwindled and his Peronist opponent, Alberto Fernandez, easily won the election primary. Given markets are naturally skeptical of “command and control” tactics, fearing they’ll lead to economic and market inefficiencies, Argentina’s stock, bond, and currency markets all fell heavily in tandem. The peso lost approximately 50 percent of its value. This exacerbates domestic inflation and worsens the debt servicing situation.

Small export base holds back balance of payments improvement

Argentina’s export sector is also rather small at just USD$5.86 billion or around 1 percent of GDP.

So, the ability to responsibly handle large amounts of external foreign exchange debt is limited. The main counterpoint to this argument would be if:

a) the interest rate on this debt is sufficiently low and,

b) the debt has a long enough aggregate maturity to limit refinancing needs.

This, however, wasn’t the case.

Because exports are so low as a percentage of overall output, it takes a large move in the exchange rate (downward) to stimulate external demand for exports and reduce or close the current account deficit (and ideally get it back into a surplus).

At the same time, a weaker exchange rate that would be necessary to remedy its balance of payments would undermine its debt sustainability by raising the effective servicing costs.

This presents the main catch-22 for Argentina’s economy. The central government wants a higher real exchange rate for the peso to ameliorate its debt sustainability. Yet the central bank wants a lower real exchange rate to balance local-currency liabilities with foreign asset valuations.