Can Oil Prices Go Negative?

This article was published on June 19, 2021.

The large drop in oil prices has prompted the question: can oil prices go negative?

On the surface, oil should always have some residual value. It’s the world’s most important commodity. So it’s commonly assumed that oil must have some type of floor price.

However, there is no reason why crude oil prices can’t go negative in theory.

The Basics Of Why Oil Prices Can Be Negative

Oil has limited storage capacity. So, carrying a large surplus is not a possibility unless more storage capacity is created. But that can take a long time.

If the oil market exceeds local storage capacity, prices can run below cash costs in order to rebalance supply with demand.

Moreover, there are fixed costs associated with shutting in crude oil production (i.e., effectively shutting it down) and restarting the process again.

Many know that electricity prices can go negative because it simply can’t be stored with the technology we currently have. Supply overwhelms demand to the point where no positive price yields a demand and prices can go negative.

This is essentially an indication to utility companies telling them to shut down power grids until the price becomes positive again.

Trade Oil

-

1

Interactive Brokers

Interactive Brokers -

2

NinjaTrader

NinjaTrader -

3

eToro USAeToro USA LLC and eToro USA Securities Inc.; Investing involves risk, including loss of principal; Not a recommendation

eToro USAeToro USA LLC and eToro USA Securities Inc.; Investing involves risk, including loss of principal; Not a recommendation -

4

Plus500USTrading in futures and options involves the risk of loss and is not suitable for everyone.

Plus500USTrading in futures and options involves the risk of loss and is not suitable for everyone.

Application to Other Commodities

Any futures contract with a physical commodity as the underlying asset may settle at a negative price when the supply of the commodity faces physical constraints in storage or distribution to such an extent that some suppliers will be prepared to compensate others to physically take away the commodity.

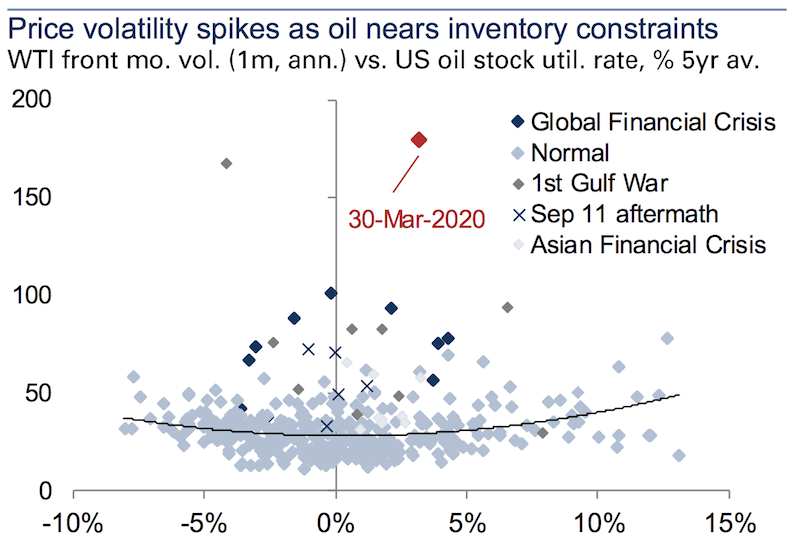

As Oil Prices Decrease, Volatility Increases

The lower oil goes, generally the more violent the market action becomes.

As oil supply gets closer to the capacity to store it, oil prices move downward. This is a further incentive to stop pumping to get supply back in line with demand. When storage capacity is available, prices will jump higher.

Understandably, because of this dynamic, there is a correlation between inventory levels and oil price volatility.

(Source: EIA, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research)

Landlocked Crude Versus Waterborne Crude

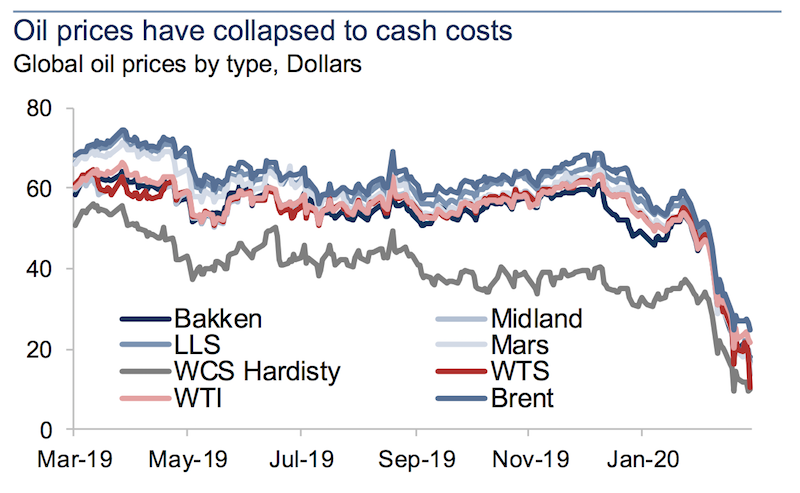

WTI (West Texas Intermediate) crude oil is also likely to run more volatile than that of Brent crude during this period.

WTI is settled in Cushing, Oklahoma, a landlocked location. Brent crude is waterborne, produced on an island in the North Sea.

Landlocked crude has to make it through hundreds of miles of pipe before it can be shipped to its final destination, unlike waterborne crude, which has direct access to a ship.

In the case of landlocked crude, such as that produced in the US, Canada, and Russia, if storage capacity is depleted, then supply can overwhelm demand and cause a shutting in of oil producing assets.

Similarly, when oil prices were hit hard in 1998, it was the landlocked crude oil versions that were hit hardest.

Canadian WCS oil is a very cheap form of oil, heavily due to its particular logistics combined with the Russia-Saudi Arabia price war. In March and April 2020, it traded at just $4 per barrel. WTI and WTS oil were similarly hit.

(Source: Goldman Sachs)

In the world of natural gas (a byproduct of shale production), we’ve also seen negative prices at some hubs. In the Waha hub near El Paso, Texas, natural gas prices have gone as low as minus-$4/mmbtu. In other words, buyers have been paid to take it off producers’ hands because of oversupply.

Fundamentally, if prices do go negative, it’s because producers either need to shut in production or else they’ll pay somebody else to dispose of a barrel given the fixed costs associated with shutting down a well.

Not The Base Case

Negative WTI oil prices is not the base case by any means. It’s a function of a temporary dislocation.

Low prices create a lot of pain among oil producers (more than what’s been inflicted already) and the lower they go, the larger the incentives to get the market back into a healthy balance.

In April 2020, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the US led a 23-country coalition to cut 9.7 million barrels per day from the global oil markets. With global production at slightly more than 100 million barrels per day, this comes to about 10 percent of total production. However, the deterioration in demand has been north of 20 million barrels per day.

The production cut prevented a further leg down, but the market remains oversupplied. It nonetheless beneficially pushes out the timeframe by which storage space might become maxed out to mid-May.

This was corroborated by OPEC Secretary General Mohammad Barkindo:

“To put this in some context, the OPEC Secretary’s assessment of available global oil storage capacity stands over 1 billion barrels. Given the current unprecedented supply and demand imbalance there could be a colossal excess volume of 14.7 million barrels a day in the [second quarter of 2020]. This oversupply would add a further 1.3 billion barrels to global crude oil stocks, and hence exhaust the available global crude oil storage capacity within the month of May.”

Demand falling by anything like 20-25 million barrels per day for just three months could have devastating consequences because it could mean increasing global inventories by approximately 2.2 billion barrels. This is about two-thirds of the OECD’s current stockpiles of 3.0 billion barrels.

North American Oil Production

North American oil is heavily controlled by private companies rather than the state-owned companies controlled by sovereign governments that typically dominate emerging market production.

These companies normally lack much in the way of scale and heavily rely on external private funding to make the business work.

While private enterprise helps spur innovation (e.g., shale), their breakeven costs are often significantly higher than the majority of national oil companies. While private companies need to make a profit in order to remain viable, governments can run deficits for elongated periods.

When influential oil-exporting nations increase their production, causing the price to fall (holding all else equal), this can drive the breakeven cost of production for some producers down so low that the business is no longer viable for them. This creates the need to acquire additional funding, roll back expenses, or find other ways of generating revenue.

Finding additional funding is hard, especially when other lenders and investors are pulling back, and generating new sources of revenue is also often not viable.

That leaves cost reduction as the most straightforward (and usually only) option. That often means shutting in productive wells. They are also doing so without having clarity on what will happen if they resume production. But North American companies have limited options with refiners, pipelines, and storage facilities filling their capacity.

On top of that, even when oil is available to sell, the low prices mean that many or most barrels are unprofitable.

Levels around $40-$45 per barrel (WTI crude) is needed for US shale production to be breakeven or just barely profitable.

This is another influence for OPEC+. They know that even if they cut production by a lot, oil prices will still very well remain low enough to keep the pain on US shale producers for a while. Secondarily, as an additional benefit, this helps Saudi Arabia (the most influential member of OPEC) maintain its strategic alliance with the US.

Supply Versus Demand

Being overly concerned about supply-side analysis generally results in problems in all sorts of markets. This goes for any type, not just financial markets. If you’re selling a physical product, the number of sellers that are in the market or how much physical supply you can produce, or procure to sell, is a secondary element.

First, you need to know how much of the product is demanded.

Do people need or want it? If a market doesn’t have demand, it’s not going to sell very well. If demand isn’t robust, then pricing power will be weak.

The same is true for stocks, bonds, commodities, or any type of financial market as well.

Any rebound in oil is going to be fundamentally driven by the demand side. April is likely to remain the low point for global oil demand.

However, there is a balancing act. When demand eventually does recover due to less strict virus-related lockdowns, oil supply will follow demand higher. There will be less incentive to constrict supply.

While the US helped broker a deal between Russia, Saudi Arabia and the rest of “OPEC+”, the Russians and Saudis are not likely to keep coordinated production cuts in place for a long period.

It is virtually impossible to run a global multinational oil organization, with a multitude of full-time and part-time members, who have very different and oftentimes mutually exclusive geopolitical goals and interests.

Final Thoughts

Can oil prices go negative?

They can potentially go negative. Oil’s floor is not low double digits, or single digits, or even zero.

When supply brushes up against storage capacity, pipelines, refineries, and storage facilities can’t physically take any more oil. This is more likely to impact landlocked oil (e.g., WTI, WCS) than waterborne oil (e.g., Brent), which doesn’t bear the same logistical constraints.

If storage capacity is maxed out, then oil producers face a conundrum if nobody is taking the oil.

Given the amount of gasoline and jet fuel on the market, refineries are slowing oil purchases. Oil storage facilities from Asia to Africa and the US southwest are filling up and physically can’t take anymore after a point. Accordingly, producers begin to shut in wells whose oil has nowhere to go.

This process of shutting down production and reopening it involves a fixed cost. At a point, producers would be willing to pay somebody to dispose of the barrel.

We’ve seen this type of process play out in other energy markets where producers pay people to take the asset off their hands (e.g., natural gas trading at negative prices in the Waha hub).

In electricity markets, prices turning negative is a common dynamic.

That’s not to say that this is likely by any means. As prices decrease, producers have incentives to coordinate on drawing back on production. But negative prices are not out of the question. Just as capital can have a negative price – i.e., negative interest rates, negative yields on bonds – where the demand is low relative to its supply, so too can commodities.

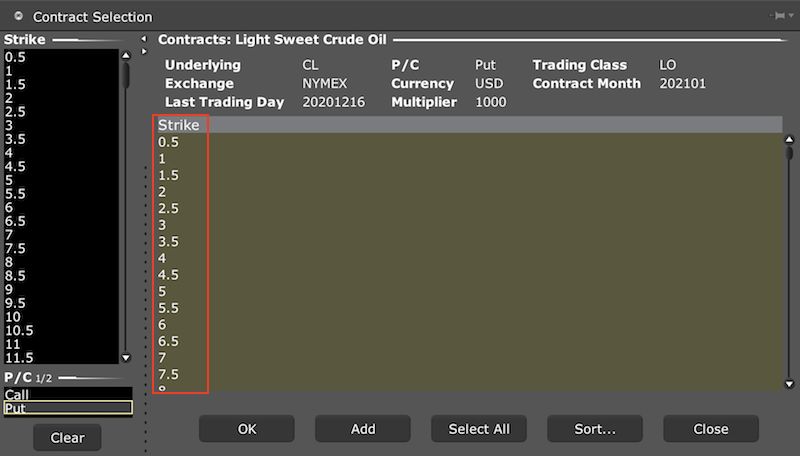

Market participants are realizing this potential and beginning to write put options on out-of-the-money maturities near zero. What interest rate traders realized more than a decade ago could become a possibility is now hitting oil traders in the same way – zero is not genuinely a floor.

(Source: Interactive Brokers internal interface)

Update

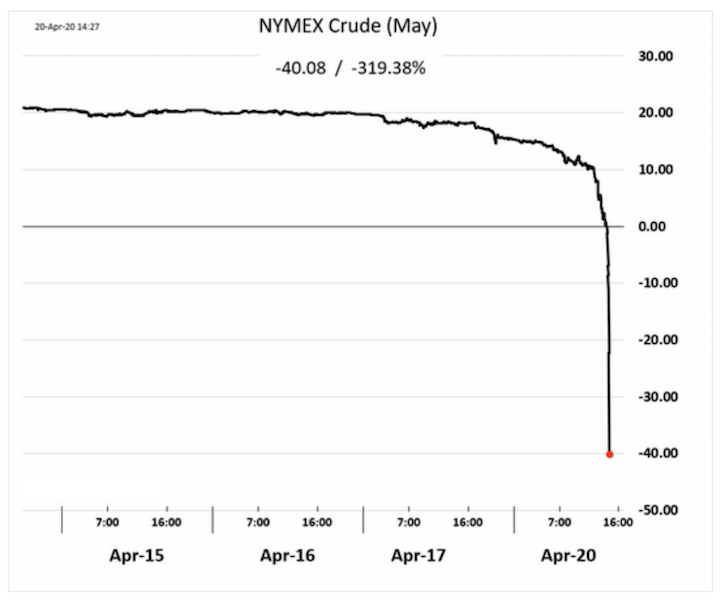

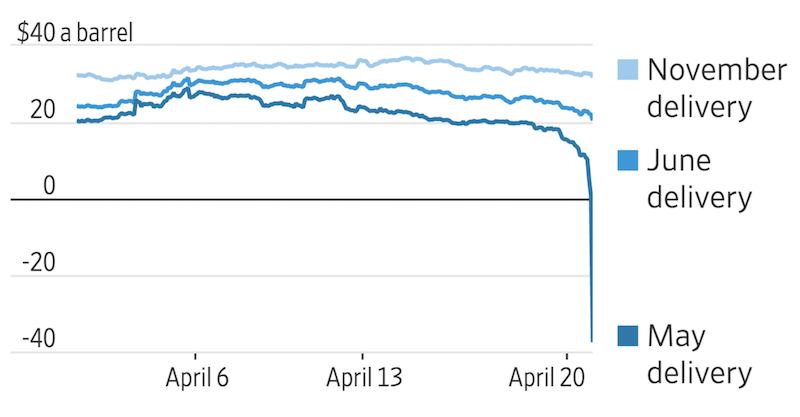

On April 20, 2020, we saw the front-month oil contract on WTI go deeply negative, at one point going to minus-$40 per barrel:

(Source: Trading View)

Looking at the spill over just the few days leading up to the crash to minus-$40. The crash accelerated once under $10, and had virtually no interruption going from $0 to minus-$40 with a lot of selling and no buyers in sight:

(Source: WSJ, Bloomberg)

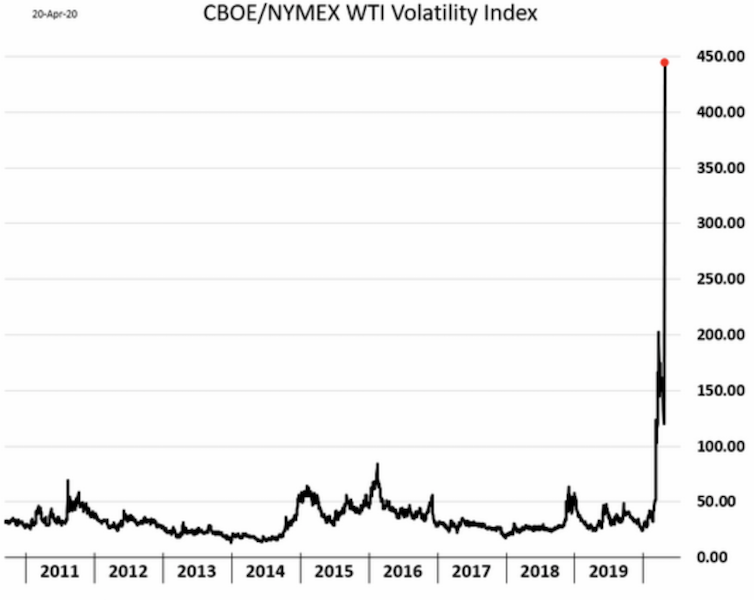

Oil volatility also hit a record high based on the Chicago Board of Exchange NYMEX WTI oil volatility index. This puts the well-known 2015-16 oil crash in the dust in terms of price and the volatility index reading. However, note that volatility models typically follow a log-normal distribution where prices never go to zero or under. That assumption is not valid as it may have been previously assumed so the reading is practically meaningless.

This is heavily a product of oil storage facilities at risk of overflowing, which means US and Canadian producers are likely to pay customer to take oil off their hands, effectively making oil prices negative.

This is especially true regarding the storage facility constraints in Cushing, Oklahoma, the WTI and main US hub.

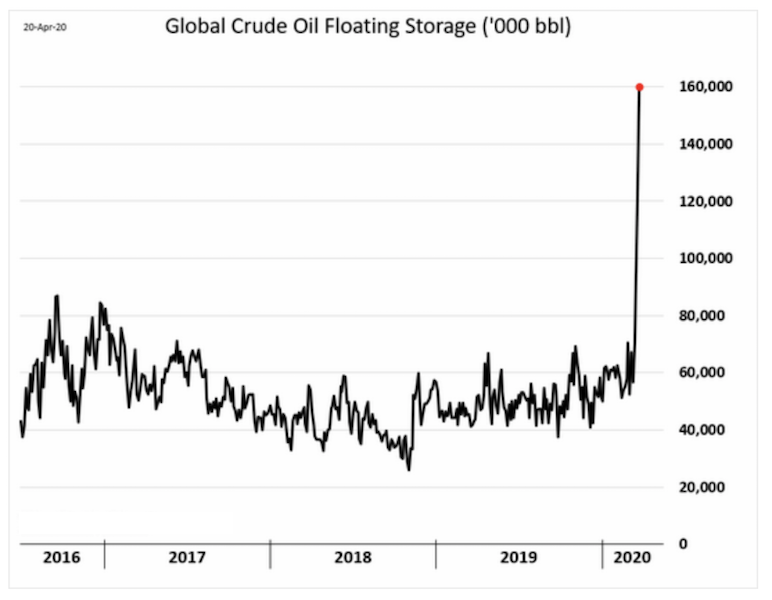

It’s currently estimated that 200 VLCCs (very large crude carriers) will be used for storage in May. This could mean supertankers may be used to hold up to 160 million barrels of oil, or roughly two days of total current global demand.

Below is a chart of oil tanker storage capacity since 2016:

There have been times historically where crude carrier ships have refused to unload oil until prices rose enough to make selling it economically viable.

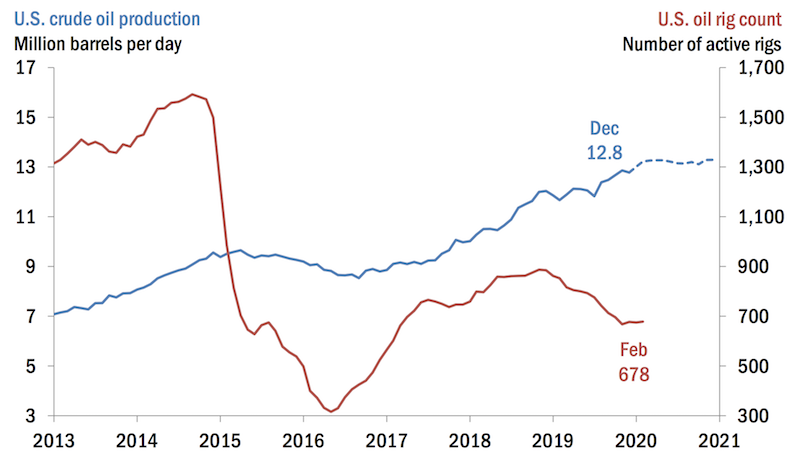

Before 2020, the US oil industry was producing about 13 million barrels of oil per day, the equivalent of about 13 percent of typical global demand of just over 100 million barrels per day. The extrapolation of daily production (dashed line) was as of February 11, 2020.

(Source: Dallas Federal Reserve)

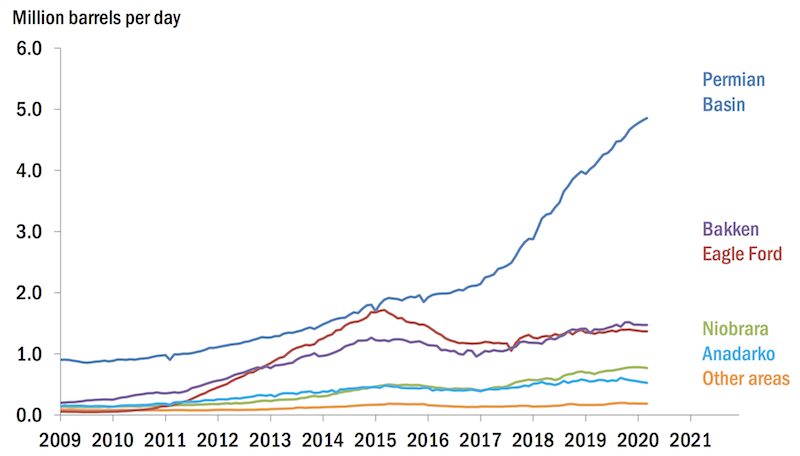

The Permian Basin accounts for a lot of this production and has grown in importance since 2015.

(Source: Dallas Federal Reserve)

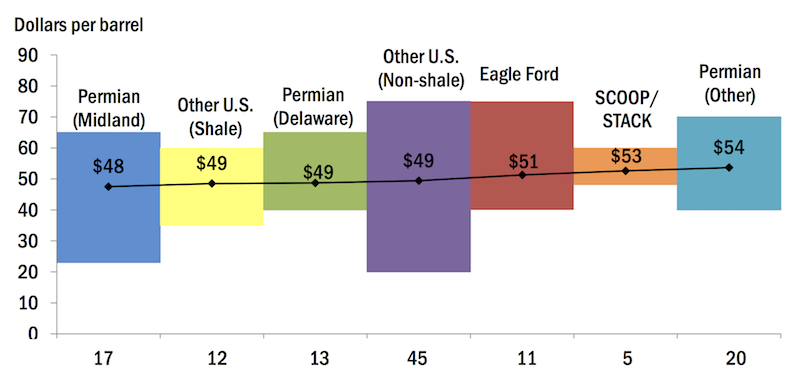

The breakeven prices for new wells by region. They all hang around $50 per barrel.

(Source: Dallas Federal Reserve)

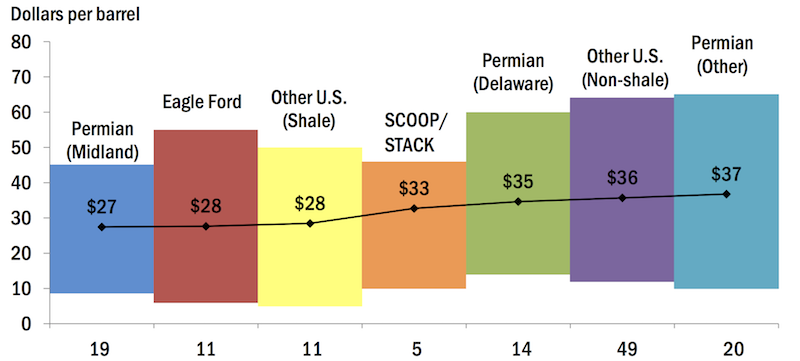

Shut in prices for new wells — i.e., oil prices required to cover operating expenses:

(Source: Dallas Federal Reserve)

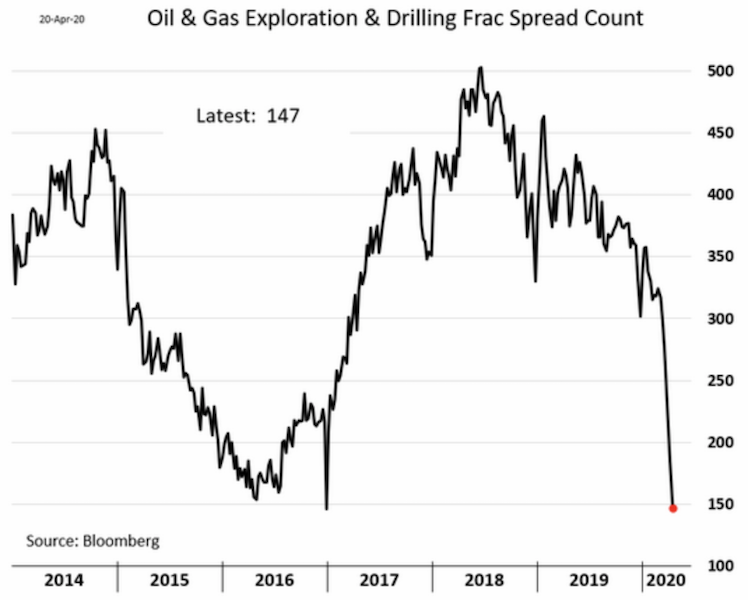

Naturally, with the massive drop in prices, fracking crews have shrunk rapidly.

Contracts further out on the curve retained a more normal price, meaning the whole oil markets wasn’t affected throughout the other contract maturities.

(Source: FactSet, WSJ)

Why the unique dynamics where you have negative spot oil prices and “normal” prices several months out?

This is what occurs when a physical futures contract isn’t able to find buyers as the contract moves toward expiration.

Because of the current state of the low demand and high supply situation, investors can see that it’s now more profitable to store oil than to pump it.

If you buy an oil contract, specifically the NYMEX WTI contract that we’re referencing in this case, that has a delivery point at Cushing, Oklahoma at a specific date. At the time this is being written, the closest contract is for May delivery. Those who hold the contract at the maturity date have to take physical delivery of the oil they bought.

That’s essentially what the futures market is – taking delivery of the physical commodity.

Those who do not want to take physical delivery or in cases where it simply isn’t feasible (e.g., most traders probably don’t want a bunch of cattle delivered to their door), they will be required to “roll over” the contract to the next delivery date. In other words, they will need to sell the current contract they own and buy the next one or some later maturity (the closer to maturity, generally the more liquid it is).

In the case of today’s oil market, the maturity of the front-month contract is tomorrow, April 21. In the days leading up to maturity, many traders sell and begin rolling over to the next contract. Typically, there is not much action during this process. Traders can sell what they need to.

During the front-month contract’s plunge to negative territory, holders were not able to resell it. Moreover, when storage capacity is very low, getting the oil delivered to you in Cushing, Oklahoma (contractual obligation) is virtually impossible.

If there is no storage in Cushing, no price available to store it, and/or the buyers of the contract aren’t aware of the physical delivery aspect as the contract near maturity (or underestimate the risk), this can lead to a collapse in demand. Liquidity in the front-month contract literally disappeared and a violent sell-off ensued.

But it’s important to note that such activity isn’t currently indicative of future expectations. When the roll officially takes place and the front-month contract is June, that currently sits at just above $20 per barrel.

At the same time, today’s action is indicative of the fact that Cushing storage is getting full and that situation isn’t getting much better with the persistent lack of demand. Q2’20 was the worst quarter in terms of economic data in most investors’ lives. The US economy, on aggreagate, bottomed in May 2020.

Oil didn’t rebound until there was an increase in demand. Further supply cuts were needed to help supplement the handling of the downturn in the interim.

Until that point, landlocked crude had a big shortage of buyers. Where storage fills up quickly, producers needed to shut in production and negative oil prices remained a risk.

Daily demand of 100 million barrels won’t be recovered for a long time – likely not until the end of 2021. In April 2020, demand was running at around 65-70 million barrels per day. Global lockdowns were drawn back slowly due to fears of follow-up waves of infection.

The crude futures market does offer hope. The market is in contango (upward sloping futures curve). But the market expects improvement. Supply cuts will only work up to a point. The drop in demand is too deep. And getting various different countries with various different motivations and geopolitical goals to agree on supply cuts past a certain point (and be compliant with the agreement) is hard to do.

While this is a difficult period for all oil producers and exporters, the lowest-cost producers and/or those who can take low oil prices for a long time (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Russia), know that there’s long-term strategic benefit in hurting US shale even if the short-term effects are negative for themselves.

Bottom line

Even with futures months contracts in positive territory, those are precarious to hold as storage capacity is getting very full. Landlocked physical oil markets, include the popular US benchmark WTI, are not in good shape.

Disclosure: No position in oil