When Will the US Run Out of Money? (And Impacts on Markets)

Can the US or any country run out of money?

Technically, the government doesn’t have money. A government is just a collection of individuals. Everything in an economy comes down to productivity.

Governments collect tax revenue from what boils down to underlying productivity at the most fundamental level. It can use a combination of those receipts and new money and credit creation to create investments that ideally pay for themselves – productivity gains in excess of the costs – ideally in a broad-based way.

Productivity is expressed through a series of transactions where one party exchanges something for another good, service, or financial asset.

Money helps facilitate the transaction, though it’s not necessary. It can also be paid with credit (a promise to pay money later) or with another good, service, or financial asset.

Some believe that government deficits don’t matter and that the government can print whatever it would like without suffering consequences down the road. This isn’t accurate, but these theories will pick up steam as countries see their deficits and debt burdens balloon, especially in developed markets.

Key Takeaways – When Will the US Run Out of Money? (And Impacts on Markets)

- The US can’t technically “run out of money” because it can “print” it. But that devalues the dollar and severely hits cash and bond purchasing power over time.

- Politicians prioritize short-term spending over long-term productivity, which worsens debt cycles and accelerates currency devaluation risks.

- When printing accelerates, traders should favor real assets (gold, commodities, productive real estate) and be careful with nominal bonds and cash.

- Currency depreciation becomes the main release valve when interest rates are near zero, raising inflation and increasing volatility across markets.

- Forward returns on traditional 60/40 portfolios will weaken.

- Traders must diversify globally, hold inflation-hedging assets, and prepare for regime shifts.

Short-term gratification over long-term well-being

It’s a natural human tendency to prefer short-term gratification over long-term results. That plays a big role in the economic cycles – most notably debt booms and busts – that we go through.

The favoring of short-term results over long-term health will cause the highs and lows of the cycle to be exaggerated.

People and companies also favor the short-term over the long-term, which hurts them over the long run. But it’s especially common among governments because of the political incentives involved.

i) They are motivated to prioritize the short-term over the long run because they’re only in office for a limited amount of time.

ii) They don’t like to face limitations and real financial trade-offs.

iii) It is not politically enticing to raise taxes much or cut back on spending.

Oftentimes, politicians like to go after where the money is (i.e., “taxing the rich”) but that can only go so far before incentives and capital flows make that a bad choice.

In addition, when tax collection is based on a heavily progressive structure (higher amounts of earnings are taxed at a high level) the system becomes more dependent on high earners. In some cases, if just one of these big taxpayers leaves, it’s felt in the budget.

Inevitably, politicians choose to borrow and spend. This enables them to:

a) provide more without having to tax more, and

b) financing the deficits is easy so long as the lenders know they’ll be getting paid back (at least in nominal terms) because the government can create its own money.

As a result, governments will borrow and spend until they can’t do so any longer. Once they reach that point the process works in reverse.

Governments often reach this point due to:

a) hard limits (i.e., commodity-based currency system)

b) currency devaluation (money moves out of the country or into other stores of value) that creates monetary inflation, and/or

c) a debt default

At this point, spending has to be cut down to the level of income. This means less spending and/or higher tax revenue.

With this comes a host of political and social problems to go along with the economic issues that result. People fight over the shrinking resources and cast blame.

The place becomes less desirable to live for those who are taxed or are subject to reduced services in the necessary cost-cutting.

Those who have money tend to have more choices, so they leave if the environment is hostile to them. This hollows out the area further in a self-reinforcing way. Tax receipts fall even as taxes are inevitably raised to try to cover the shortfall, continuing the spiral until there’s a debt and political restructuring.

Over this time, to make the debt burdens easier to handle, the government typically has a negative real interest rate on its cash and debt. This makes both cash and bonds unattractive to own.

Can money be printed?

The single biggest factor on how the shortage of money plays out – i.e., too much debt relative to income – is whether money can be created or “printed” in order to fill the gap.

People still suffer if money can be printed. But the circumstances are different.

When money can’t be printed – typically because the debt is denominated in a foreign currency, which is common in emerging markets – debts can’t be covered with money. Austerity results and income has to contract down to spending.

When money can be printed, there will be enough money created (usually more than enough) to service the debt. The trade-off is that the value of money will go down.

Currency devaluation is a type of discreet tax. It also tends to stimulate nominal economic activity and certain types of assets like stocks, which see their values rise if done at a sufficient enough level to offset any economic destruction that might be occurring.

So generally in the short-term money printing is beneficial, especially if you have a reserve currency. This means there’s a lot of demand to save and transact in the currency, which means you can sell debt to fund your deficits to the extent that such debt is wanted.

Because money printing gives a short-term jolt, it’s much more politically acceptable than taking debt problems through lower incomes and/or lower spending.

Even in circumstances where money is “hard” – i.e., money is tied to a commodity like gold – they will either alter the convertibility factor to get more money into the system, or they’ll sever the tie altogether. The US did in 1933 and 1971 when it broke the gold standard.

Printing money devalues debt and money.

There is lots of talk nowadays about how producing a lot of debt and money is possible without suffering bad consequences, but there’s a mechanics to doing that and there are very real trade-offs to pursuing those policies.

For example, in 2008, there was an economic crisis.

The US, the central bank printed money to make up for the income shortfall. This was mostly in the form of lowering interest rates and buying financial assets.

These steps were necessary. But it mostly benefited those who were prepared for it – those who own financial assets because that’s where the money went. Lowering interest rates increases the present value of future cash flows and QE involves literally buying financial assets.

One of the key trade-offs is that it intensified wealth gaps, which were already large. Conflicts increased between different groups of people. And it shifted the country into a period that increases the odds of some form of a restructuring.

While the adrenaline shots feel good in the present, the future eventually comes and the trade-offs that once seemed more favorable become less so and the range of policy options is more constricted.

In the US and most of the developed world, the range of options available would be wider if those making the decisions had made decisions that put long-term health over short-run gratification.

When you have a zero short-term interest rate and a zero or near-zero long-term interest rate – these can be viewed by looking at a yield curve – that’s a reflection that you’re nearing the constraints of how far you can expand credit and create money.

The policy focus shifts more into the fiscal side, where elected officials must direct where the money will go and central banks back that up by supplying it.

There’s more room for good because politicians can more easily direct money where they want it to go. When you raise and lower interest rates you change the general economics of borrowing and lending and the “invisible hand” essentially enables that to work its way through the system.

But there’s also more room for bad if the decision-making isn’t effective as it could be, such as the potential for more currency depreciation.

It boils down to human nature and how the present is emphasized over the future. So the cycles we experience end up being more painful than they would otherwise be.

Does the Fed make money?

The Federal Reserve can – and often does – make money for the central government.

The Fed is a self-funded government agency because it has the authority to create money.

And as a self-funded agency, the Fed collects interest on the bonds it owns. It buys the securities with money it creates by fiat. It also charges fees for services for banks.

After the Fed covers its expenses, it turns over the excess to the Treasury Department.

The importance of productivity

Printing money and creating debt and how to divvy it up has its role in terms of how the government can direct resources.

But ultimately what is done with that capital is important.

On it own, money doesn’t have any value. Underlying productivity gives money its value. If the supply of money rises faster than total productivity, it will become devalued. An inflation rate that’s low and steady (around zero or a little bit above zero) is healthy for an economy.

Productivity is the rate at which knowledge is gained relative to what’s lost. This enables societies to create more, invent more, and do more over time that helps improve living standards.

Productivity underlies everything. So for policymakers it’s not so much about just figuring out how to divide the pie, but also about fostering productivity to grow it.

It is vital that the debt and money being created is used to produce productivity gains and a favorable ROI that’s as broad-based as possible.

If the cost-benefit analysis is ignored or deemed unimportant and money and credit is given away that doesn’t yield productivity gains that benefit the whole, the devaluation of this money and credit will reduce the buying power of the government and everybody else along with it.

It is perfectly appropriate for the government to use its status as the lender of last resort so long as the capital produced provide a return on investment that’s adequate enough to service the debt.

Incomes exceeding productivity, and debt growth exceeding incomes is the basis of all of how our big cycle economic problems occur.

The role of politics

It’s the case in most democratic countries, especially the US, where the choice is between:

a) becoming more unified in supporting a capable, moderate, bipartisan leader, which would require those with different views and perspectives to not get exactly what they want but will provide them more balanced policy outcomes in which the system remains intact and works more effectively, or

b) dysfunctionally fighting for exactly what they want, which will give them ineffective decision-making and a greater risk of some kind of major internal conflict where raw power can become more important than whatever the law says.

There’s little chance of choice A considering the circumstances we’re in along with who presidential candidates are likely to be going forward and the number of extremists relative to moderates in Congress.

In a democracy in which there are both a) weak fundamentals that are leading to painful circumstances and b) high levels of fragmentation in political decision-making, one is destined to be an ineffective/failed leader.

Being a leader of a country in which the people are obsessive about fighting with each other and tearing down bipartisan efforts creates a very messy situation.

The US is in the classic stage of its arc where it is no longer economic to run, leading to painful trade-offs that will become more acute over time. When any government, company, or individual spends more than it earns and has liabilities greater than its assets, bad outcomes are inevitable.

The US is in the very privileged position of having the world’s top reserve currency, which allows it to paper over its bad finances in the short run by monetizing deficits.

The loss of this reserve status is what would effectively lead to forced budget controls (spending has to contract to the level of income, which is based on productivity), and lots of defaults, debt restructurings, and painful cuts in real incomes.

We’re clearly in the phase where central banks face the choice between:

a) allowing money and credit to tighten and interest rates to rise, which is depressing especially for those who are the most over-indebted, and

b) printing money to help the most indebted service their debts and keeping real interest rates artificially low, which devalues their money, raises inflation, and increases debt, which is a type of short-term fix that just makes the problem worse down the road.

How will you determine when a government will run out of money?

In emerging markets it’s easier to ascertain when debt problems will emerge because they usually lack reserve currencies and the tools necessary to service debt. So, they usually go into default if they don’t get emergency lending.

They must solve these problems by cutting back incomes to their level of spending to reduce deficits.

When a currency devalues, they can afford fewer imports and their exports become cheaper for other countries. That helps close any current account deficit that might exist.

But if they have a lot of foreign-denominated debt, it’s like a big surge in interest rates because their money no longer goes as far.

They might also look toward certain organizations like the IMF to get financing to help them pull out of their economic problems.

In developed markets, they typically have reserve currencies to varying extents.

When there’s demand to hold the debt internationally it’s much easier to fund any gaps and spend beyond your capacity.

But getting a reserve currency from:

- dominance in trade, technology, economic power, capital markets development and overall size, military, and geopolitical strength…

then…

- overspending in the reserve currency and becoming indebted…

and…

- leading to the relative decline in the empire as its financial health deteriorates…

…is a classic economic problem that happens over and over again historically.

Nobody knows when the fiscal government will run out of capacity to fund their deficits.

Right now the USD, as the world’s leading reserve currency, is still in large demand globally, which means there’s still the ability to sell a lot of debt. So, it’s not necessarily a short-term problem.

Deficits, in the long run, however, are rectified through movements in relative exchange rates and currency devaluations.

The trade-off that’ll become more acute over time is to either:

a) allow interest rates to rise to unacceptably high levels to defend the currency (compensate investors enough for holdng USD money and debt), or

b) print money to buy the debt and devalue the dollar when there’s a shortfall of free-market buyers of it (like now).

They can’t do the first because debt servicing costs will climb too high and credit creation will be stunted.

Credit, like money, confers spending power. And one person’s spending is another person’s income. So it means lower incomes and pulls forward all the bad economic, social, and political consequences.

It’s a problem that gets worse over longer time horizons because the interest rate received on the money and debt aren’t on par with the rate the currency is declining due to the underlying capital flow (money moving into other currencies and things/stores of value that give better prospective returns).

That’s why governments often ban gold or impose foreign exchange controls to control the outflow.

It also means things like bitcoin and cryptocurrencies are at risk of government intervention if they become big enough. Sometimes they’ll impose wage and price controls, though they tend to just create distortions and aren’t very effective.

The devaluation goes on until a new balance of payments equilibrium is established.

This means you get a large enough level of forced selling of real and financial assets and enough reduced buying of them by US entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

This is the point that entails the loss of reserve status. And the loss of reserve status effectively means forced budget controls – or further currency depreciation and the ill effects of that if overspending continues.

It means Americans can no longer spend as much, so the social and political consequences will be bad. And once you get to that point, there’s nothing policymakers can do about it.

It’s simply a self-correcting mechanism from the excessive spending patterns of the past. You can’t spend beyond your means forever. It’s true for any individual or collection of individuals (company or government).

How much any entity can spend beyond their means in the short run depends on their creditworthiness and whether the debt is being deployed effectively to obtain a positive ROI.

Reserve currency status is traditionally the last thing to go when an empire declines, so the US will milk it until they can’t anymore.

Costs vs. Outputs

The high costs apply to lots of things.

Social programs are very costly. Building the defense is very costly. The idea of needing more US-based production to get away from dependence on overseas manufacturing is very costly.

Is that money going to be spent (i.e., invested) productively to get the desired outcomes within the desired timeframes?

The US federal government does not have a positive ROI on its spending, which is natural when empires get to a certain level of size where they have a certain level of fixed costs and a level of productivity that isn’t commensurate with those commitments.

So, in the short- and medium-term, as long as you continue to have good creditworthiness, you run a larger deficit over time.

To get the money, you either tax it (which you can do up to an extent) or you issue debt to fund it and the central bank “prints” money to monetize whatever amount of debt the private market doesn’t want to avoid an unhealthy rise in interest rates.

(If interest rates rise too much it contracts private credit creation and economic activity, which impacts incomes, living standards, your tax base, and so on.)

An essential ingredient is that the debt and money that’s created is used to produce productivity gains and favorable return on investment rather than just being given away without yielding productivity and income gains.

If it’s given away without yielding these gains the money will be devalued and its buying power will be reduced.

A country cannot sustainably run deeply negative real interest rates (i.e., nominal spending – (productivity + labor growth) – nominal interest rates).

If a country burns its creditors like this, then it’ll have more trouble finding them, which risks currency problems and impacts its ability to spend in excess of its income going forward.

The way the US takes its reserve currency status for granted given the way it runs twin deficits (fiscal and current account) is a longer-term problem because the global bias to hold dollar-denominated credit is a key ingredient in how far the US can push its spending in excess of its income.

Right now the dollar is fine because of what’s been a growing interest rate differential between the US and other countries, but once that passes through the currency challenges will be a bigger issue in managing the cycles. The balance of payments/current account deficit is a bigger driver of the dollar than the fiscal side.

If the amount of money being lent to finance the debt is not adequate, it’s perfectly okay for the central bank to create the money and be the lender of last resort as long as the money being invested has a return that’s large enough to service the debt.

History has shown that investing well (i.e., so that it yields productivity in excess of its costs) in education (in its various forms, including job training) at all levels, infrastructure, and research that yield productive discoveries has worked well.

Throughout financial history, large education programs and infrastructure programs that were done well have paid off in nearly every case, even though they have long lead times.

Even when financed by debt, improvements in education and infrastructure (among other supply-side stimulus) were important ingredients behind the rises of virtually all countries/empires and declines in the qualities of these investments were almost always reasons behind their relative or absolute declines.

Impact on Financial Markets

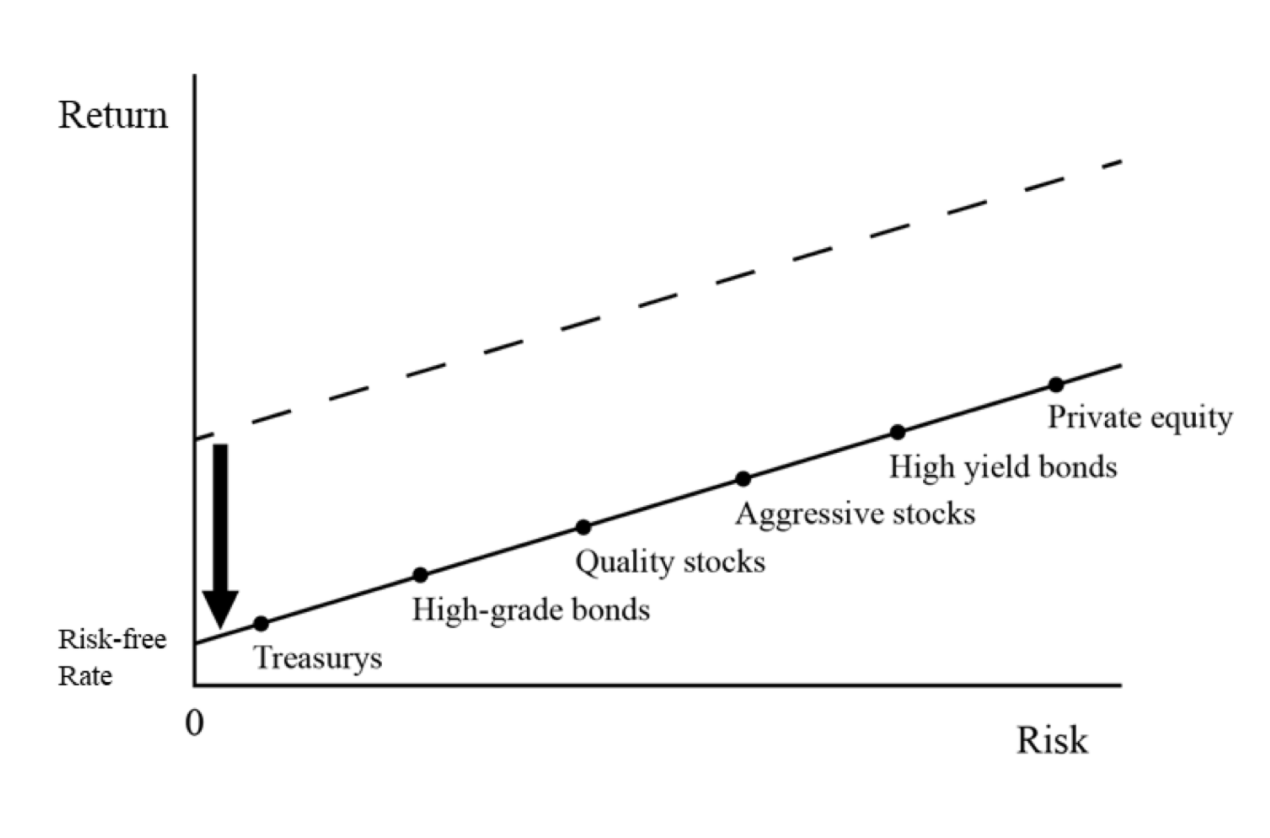

Monetization is good for certain types of assets and bad for others.

Money printing and currency devaluation is bad for cash and bonds, and good for stocks, commodities, and gold.

Cash and bonds are bad in that environment because they’re printing and creating a lot of it. And when short-term and long-term interest rates are at or near zero, that typically means real interest rates are negative.

Central bankers are always going to target an inflation rate of at least zero. If real interest rates are negative, that means your wealth is being destroyed.

The entire purpose of putting your money in the markets is to get more purchasing power over time.

If putting your money into certain things causes that to go backward, then you’re going to want to find something else.

That something else is whatever the monetization benefits. Where is the government directing that money? What other assets will benefit.

So the general playbook is:

a) understand where wealth is being destroyed in such an environment and avoid that, and

b) know what assets benefit in a monetization environment

Where to put your money

So when the returns on cash and bonds are low and there’s a lot of it being created, you have a few main alternatives:

i) inflation-linked bonds (ILBs such as TIPS)

ii) gold, precious metals (e.g., silver, platinum, palladium), and certain types of commodities

iii) different countries where the environment is different

iv) stocks and companies with stable cash flow

We’ll go through each individually.

Inflation-linked bonds

Nominal rate bonds are risky investments with little upside when the interest rates on them are around zero.

Nominal interest rates can only go so low – about zero or a little bit below.

Inflation is always going to be targeted at a positive level, so your real return is negative. And the price risk is high because there’s no limit to how high interest rates can theoretically go. If inflation picks up and real rates normalize, there’s that asymmetry.

Switching part of the allocation away from nominal rate bonds and into inflation-linked bonds is one option.

Nominal rate bonds still retain some level of diversification to a deflationary environment, but inflation-linked bonds can still perform well even if real interest rates continue to decline.

There’s no limit to how low real rates can decline. Real interest rates are a function of nominal rates minus inflation. So inflation-linked bonds don’t have the type of “price ceiling” constraints as nominal rate bonds.

Overall, the price upside on a bond yielding 0 to 2 percent is small relative to the downside. And the returns are very likely to be negative in real terms, so the real income generation potential is negligible.

Gold, precious metals, commodities

Gold functions like the inverse of money or a type of long-duration, store of value asset. It’s a function of the value of the money used to buy it. When gold goes up or down, it doesn’t have much to do with its utility or industrial demand.

Gold functions much more like a currency than a commodity subject to supply and demand in its consumption. It’s the third-largest reserve asset held globally behind dollars and euros.

Over the long-run, gold’s price is a function of currency and reserves in circulation relative to the global gold supply. Generally, when more money is created relative to gold, the price rises, though there’s plenty of volatility in the gold market.

Gold is more volatile than the S&P 500 and a little more than twice as volatile as the US dollar.

Traders and investors buy gold as a type of protection against their own currency, as gold is no one’s liability and can function as a type of currency alternative or reserve asset in a limited capacity. It is much less liquid than traditional sovereign bond markets.

It can be helpful to have in a portfolio in a time like today when central banks are creating a lot of money to service debt. Unlike fiat money, nobody can “print” gold.

Inevitably, when a country has too much debt (it owes too much money), and it has an independent monetary policy that enables it to create money, it will print what it needs to prevent the debt from becoming a problem. This is especially true if they have a reserve currency.

The biggest part of the debt matter at the sovereign level is whether the debt is denominated in the country’s own currency or in a foreign currency.

When it’s denominated in a country’s domestic currency, they can handle it in the usual ways:

i) Change the interest rates on it

ii) Write-down some or all of it (a 30 to 40 percent write-down is fairly typical in major debt crises)

iii) Change the maturities on the debt in order to spread out the burden

iv) Change whose balance sheet it’s on

Although the main developed economies (US, developed Europe, Japan) and China have debt loads that are too high relative to income, the debt is heavily denominated in their own currency.

In places like Turkey and Argentina it’s a different story.

They can control the situation as a result if they’re proactive about it.

If they write some of it down, change the interest rate on it, and spread it out such that they only have to pay a manageable amount each year, or if it debt goes from the individual or corporate level (who are not able to print their way out of their debt problems) to the government (if they can print) then it becomes much more manageable.

All the new money creation has implications for the value of money.

No country can create money, issue debt, and have chronically large deficits without impacting the soundness of their currency.

This is a driver of gold and why it does a reasonable job of inversely tracking the path of real interest rates of the currency it’s referenced against. When a currency goes down in value, gold goes up in money terms and money goes down in gold terms.

The lower financial assets yield, the more people look for alternatives. It’s a type of currency hedge. This goes for stocks and other types of commodities and real assets as well.

Silver serves a similar type of purpose and has also been used as money throughout history like gold.

But silver has industrial uses, which makes it correlate to the credit cycle. So it’s less of a diversifier.

It’s also an even smaller, less liquid, and more volatile market than gold. If one wanted to allocate to both gold and silver, most would allocate less to silver given those factors.

Looking at other countries’ markets

There are other countries that have positive nominal bond yields, so those are an option to make money on nominal rate bonds if the global disinflationary trend continues.

Traders and investors from the US tend to take a US- and Western-centric view of the investment world.

But what’s representative of the US and the developed world is less representative of the East.

And these factors can persist because the conditions between them are different. But more and more investors are switching their allocations more to southeastern Asian (China and others) and away from the low yields in the US and developed world.

In many parts of the East, you have a normal cash rate with a positive real yield and positive nominal bond yields, while cash and bonds are largely wealth destroyers in developed markets.

As a whole, investors are overly focused and concentrated in their home markets. That goes for their currency as well. Most pay a lot of attention to whether the assets they have are going up or down but not much attention to what their currency is doing.

As trading and investing is all about growing real spending power. And gains are not just account equity gains, but equity and currency.

So currency diversification is valuable. It’s especially so when many currencies are being actively deprecated because of the big picture related to various countries’ intractable debt problems. This makes them essentially reliant on negative real interest rates.

That means investors in these areas are probably going to want exposure to other assets from other countries, other currencies, and other assets that are of a non-financial character.

Capital is always moving around. For those typically highly concentrated in stock portfolios, that’s a big concentrated bet on a state of the world where the US dollar and US equity market does well. By and large, it’s an extrapolation since the American world order (1945 to the present) has been a reality of everybody’s lives.

The policies that were pursued to push US equities higher – low interest rates, QE and money printing – have brought forward those returns looking backward but have lowered their returns going forward as there are constraints to the efficacy of those policies when rates hit zero.

The returns of the future, especially in real terms, will be nothing like the returns of the past.

The US policy mix is bidding up US asset prices and is good in the short term. But that lowers risk premiums.

And low risk premiums and negative real interest rates on a large bulk of assets means money is eventually incentivized to leave the country.

So one can expect that it’s important to have exposure to the assets of other geographies and currencies as well.

Capital will continue to shift more from West to East. This is because emerging Asia is growing faster and becoming a rising influence in the world.

Productivity rates are 0.5-1.5 percent annualized in the developed world. Over in the East, you commonly have 4.5-6.0 percent.

And what are common industries in the US are growth industries in China and other parts of southeast Asia simply because they didn’t exist before.

The US’s reserve status will not last forever, but is safe in the near-term

While the world is accustomed to the US dollar as the world’s top reserve currency, the US’s financial situation is putting this at risk (eventually).

The US is now just 20 percent of the global economy yet still around 60 percent of global payments and international debt. That eventually has to come closer in line.

The US isn’t going to raise its growth rate to take more from the world on a relative basis because of the limitations in productivity growth. It’s the currency that will have to come down over time.

But it’s not going to happen overnight. Loss of reserve status always comes with a lag after an empire’s relative standing fades.

But if the dollar isn’t used as the primary currency in global transactions, then what is used in place of it?

That’ll take time to move into a new system. But more capital will shift out of the US dollar over time.

Certain stocks and business

Certain stocks involve selling products that people always need. They can be thought of as consumer staples. Companies that drive big productivity gains can be thought of in the same way as good stores of value.

Companies involved in creating the technology that’ll drive the big productivity gains going forward (e.g., 5G, quantum computing, AI chips, data and information management) can serve the same type of purpose in a portfolio.

These companies don’t rely on interest rate cuts to help offset a loss in income and are expected to reliably grow their earnings over time.

They can function like a type of fixed income alternative in some capacity.

They won’t have the big ups and down like companies that are highly tied to how the economy does, like a manufacturing business.

Cyclical businesses rely on interest rate cuts to offset the drop in earnings to get the bottom in the markets. In a normal recession, there’s an interest rate cut of about five percentage points (500bps). But when you’re out of interest rate room, that’s no longer reliable. It’s more on the politicians to help you, which they might not want to do or have the ability to do even if they wanted to, depending on the limitations they face (based on politics or economic reality).

Something like restaurant business is not necessarily a good store of value because people don’t have to go to restaurants. The same thing with malls and movie theaters. People don’t really have to go to the mall with so much commerce now done online or go to the movies when they have other entertainment options.

Differentiation between countries and sectors

In a world where interest rates and QE are the main drivers, which change the economics of borrowing and lending. The interest rates that result from that move through the system. A rising tide tends to lift all boots.

At the same time, it’s not very targeted. In a world where fiscal and monetary must be unified, more of the control of the economy falls onto the politicians. Elected officials have more of a role in dictating who gets money and support and who doesn’t.

It also has influence on a country level because different countries have different capacities.

It’s generally true when you get to this state of the world where:

- traditional policy is out of room

- more policy decisions are directed by politicians,

- you see differences in behaviors and spending patterns due to a atypical or special events, and

- there’s more conflict between countries such that they become self-sufficient rather than open and reliant on others…

….that you’ll get wider divergences and the averages won’t be representative of much.

The US has a reserve currency so it will print money and create debt and that’ll go into financial assets. The EU and Japan will also do so to a more limited extent, as will other countries that have somewhat of a reserve currency (UK, Canada, developed Oceania).

But, as mentioned, emerging markets have much more limited capacity. Their response may not be anywhere near the same, as it can lead to balance of payments issues when nobody wants to hold their debt, which causes the money to just go into inflation.

Ultimately, the limiting factor on government printing is inflation (of goods and services).

Protection against inflation

Most people in the US haven’t experienced much in the way of inflation before. High double-digit inflation hasn’t been seen in the US since the beginning of the 1980s.

Older policymakers tend to be more mindful of the possibility than younger new-age officials just because of life experiences.

But once you get monetary and fiscal policy moving in the same direction the possibility is more likely that you can get inflation.

For the most part, monetary and fiscal policy have been moving in different directions in most of the developed world for quite a while.

The US had a fiscal surplus back in the early 2000s. Post-2008, monetary policy was loose but fiscal policy was relatively tight.

The exception was the last few years of the Trump administration where fiscal policy became looser, but the Fed responded by being tighter by hiking rates even without a pickup in inflation.

The Fed began easing back off its expectations in late-2018 and throughout 2019, which came after the fiscal easing began washing out.

There are different types of inflation.

i) monetary inflation

ii) demand for something in excess of its supply

Monetary inflation comes from currency weakness. This is a material risk when interest rates are at zero and more economic decision-making falls into the hands of elected officials, which creates more room for both good and bad.

If a currency depreciates, the money doesn’t go as far, which makes other stuff go up in price in relation to money. Imports become more expensive (inflation) and exports become cheaper (deflation to the rest of the world).

So one country’s inflation can be another’s deflation.

There’s also the supply and demand functions of inflation.

An economy is made up of three basic things – capital, labor, and commodities/raw materials.

Inflation is largely a function of demand in excess of the supply of something.

If costs are going up, that means industrial commodities could be uniquely suited as a type of inflation-protection asset.

Most commodity baskets are heavily centered around oil and energy. But if governments have carbon, environmental, and climate policies they’d like to pursue, that could cause increased demand for many types of industrial commodities.

If the world were to strive to meet things like the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals that’s going to cause a whole lot of extra demand for things like copper, lithium, cobalt, aluminum, agricultural, and other industrial commodities.

So constructing a commodity portfolio that’s less reliant on oil and energy and more into the things that could benefit going forward can be both return-enhancing and risk-reducing.

Something like gold can be a reasonable counter against monetary inflation while a diversified commodities portfolio can be a good counter against supply and demand related inflation.

Inflation-linked bonds, of course, can play a role in a portfolio designed to counter against inflation risks.

How much to hold?

Striving for a portfolio allocation of about 10% dedicated to gold and precious metals and 10% to a diversified commodities portfolios can be reasonable benchmarks to consider.

Can cryptocurrency be a part of it?

Cryptocurrencies and their rise are largely a function of the environment we’re in. When cash and bonds yield so poorly, the money goes looking for something else.

A lot of the flows are speculative. But some increasingly view cryptocurrencies as a potential store of value.

Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies don’t yield anything (though crypto savings accounts with a yield are now a thing). But like a lot of things that don’t yield anything (gold, precious metals collectibles, commodities, some forms of real assets), that doesn’t matter as much when the yields on other things have gone down.

The fall in short-term interest rates reduces the return on all else

Volatility is the main issue with cryptocurrencies when it comes to portfolio construction. That means if you’re trying to have a relatively balanced allocation that can weather everything the world throws at it, even having just a sliver in cryptocurrencies can bring a lot of risk.

Even if you put 10 percent of your allocation into bitcoin and the rest in the S&P 500, 63 percent of your risk allocation would be in bitcoin just because of how volatile it is.

| Portfolio | Name | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| 90% Stocks | SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust | 36.57% |

| 10% Bitcoin | Grayscale Bitcoin Trust (BTC) | 63.43% |

Is there a path to recovery for governments that spend too much?

Yes, there is a path to recovery for governments that spend too much, but it requires disciplined, preemptive action anchored in structural reform rather than short-term fixes.

The key is setting a clear fiscal target – for example, aiming to stabilize the deficit at around 3% of GDP.

More generally, a level commensurate with GDP (so the GDP-to-debt ratio stabilizes) or based on organic demand for the bonds that finance the deficit.

Without stabilization, debt compounds faster than economic growth.

This, in turn, eventually leads to a tipping point where markets lose confidence, interest costs balloon, and forced austerity becomes unavoidable.

To achieve stabilization, a three-pronged policy strategy is needed:

- Moderate but meaningful spending reductions across non-essential programs (e.g., 4% of GDP), focusing on entitlement reforms and inefficiency cuts rather than slashing productive investments.

- Gradual tax increases/revenue enhancements (another 4% of GDP) targeted in ways that minimize economic distortion, such as broadening the base, closing easy arbitrage opportunities, and aligning taxes with long-term growth incentives. A lot of this relies less on “taking” and more about growing productivity.

- Reducing the real cost of debt by maintaining interest rates below nominal growth rates. This can be achieved through financial repression (i.e., holding interest rates below inflation to reduce debt burdens), central bank support, or strategies that anchor inflation expectations slightly higher (e.g., 2.5% instead of 2%) without destabilizing the currency. In 2020, the Federal Reserve officially adopted an average inflation targeting (2%) framework that was a step in this direction so 2% is viewed as an average instead of a ceiling.

This approach emphasizes shared adjustment across political and economic sectors, which is critical because it creates social problems when one group bears all the burden.

Importantly, like what’s been seen in the past and in other societies, policymakers can embed automatic fiscal stabilizers. This way, if political consensus fails, pre-agreed cuts and revenue adjustments trigger by default.

This builds resilience against the cycles of political dysfunction that often accompany fiscal stress.

Moreover, pairing fiscal tightening with monetary accommodation – easing interest rates or supporting financial conditions – can offset recessionary forces and falls in risk assets that spending cuts and tax hikes would otherwise cause.

History shows that when fiscal discipline and monetary support are synchronized, debt-to-GDP ratios can stabilize or even decline without triggering bad economic and market outcomes.

Strategic view

Recovery isn’t just about balancing numbers.

It’s about preserving faith in the government’s ability to manage its obligations over time.

If credibility is lost — if bondholders begin to fear either default or runaway inflation — then the costs multiply and options narrow.

Acting early, moderately, and credibly creates a “soft landing” path.

Delaying action, by contrast, risks a much harsher, externally forced adjustment later: currency crises, inflationary spirals, capital controls, and loss of reserve currency privileges.

The real question is whether political systems – particularly in democracies where short-term interests dominate – can muster the will to undertake shared sacrifice before crisis forces it upon them.

The trader and investor’s view

Structural reform is unlikely, so traders/investors should prioritize building strategic resilience over tactical positioning.

Focus should be on high-quality companies with strong margins, clean balance sheets, and global revenue exposure.

Allocate to real assets like gold, productive real estate, and carefully selected commodities as hedges against monetary debasement.

Diversify geographically into countries with strong fiscal positions and maintain shorter-duration or floating-rate fixed income for optionality.

Finally, hold cash, use tail-risk hedges, and embrace volatility exposure to navigate the inevitable turbulence from fiscal and monetary instability.

Conclusion

Most governments can print money, so those that can print can meet their obligations in nominal returns, if necessary.

Policy constraints kick in when interest rates are around zero. No longer can the economics of borrowing and lending be changed as they normally can.

Instead of policy easing going through the interest rate channel, the vulnerability is the possibility of it going through the currency channel.

This can produce monetary inflation where cost pressures become higher than normal and policymakers are forced to face more acute trade-offs.

Portfolio construction in such an environment is centered around two ideas:

i) avoiding the places where wealth is being destroyed, and

ii) going into assets that benefit from monetization policies.

These assets can include:

- inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

- gold, precious metals, industrial commodities, and other real assets

- different countries that have different conditions, where owning cash and nominal rate bonds make more sense because the real rates on them are positive

- certain types of stocks and income-generating businesses

Portfolios that did in the past – such as one loaded heavily with stocks or a 60/40 stock/bond mix – are not likely to do as well.

Those portfolios look good looking backward but the conditions that brought those tailwinds are largely no longer with us, meaning forward returns are likely to be poor, especially in real terms.