The UK’s 2022 Fiscal Mistake – An Example of Fiscal Policy’s Impact on Currencies & Markets

In September 2022, the UK imposed a tax cut as an attempt to stimulate the economy.

In this article, we cover the broad-level impact of this fiscal proposal on financial markets.

Financial Market Impacts

That led to the plunge or UK currency, bonds, and financial assets because the tax cuts were unfunded (i.e., they lead to a larger fiscal deficit).

GBP/USD

Unfunded expenditures require the selling of additional debt (bonds) in order to pay for them for which there wasn’t the demand for by the private market.

Pressure on the currency or interest rates

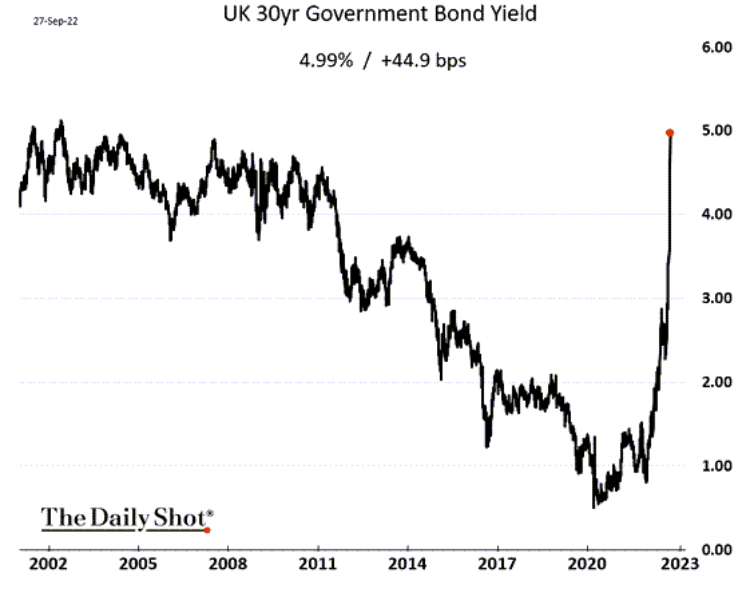

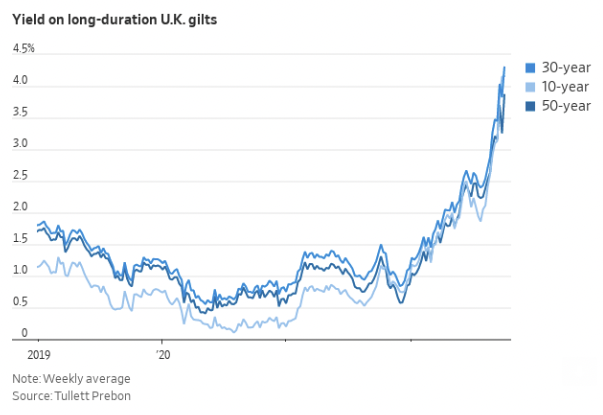

This means either interest rates have to go up due to the supply-demand mismatch in the bond market. Namely, investors need to be compensated more in order to buy the bonds.

If they aren’t, they sell.

Easy money policy that’s done toward the beginning of a business cycle to get markets and the real economy going again brings a host of risky practices, such as borrowing short term to lend long, “reach for yield”, and leveraged arbitrage: buying one asset while selling short something similar.

When interest rates go up, short-term loans become harder to refinance, risk asset prices decline, and leveraged investors are forced to sell to meet margin calls.

This dynamic plays out everywhere:

- derivatives

- equities

- corporate debt

- emerging-market debt and

- mortgages

In past crises this showed up in Mexico’s default in 1982, the stock market crash in October 1987, the bankruptcy of Orange County, California in 1994, and the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

The 2021-23 tightening cycle is the fastest since the 1980s and will inevitably trigger similar things as a result of the knock-on effects of changing the economics of various lending relationships and financial market strategies.

British pension funds’ leveraged positions in gilts that came to the surface in September 2022 was one such event.

All medium- and long-duration gilts went up at the same time.

If the rise in interest rates is too much such that it negatively impacts private sector credit creation (and therefore economic output), then the Bank of England can digitally create the money to buy the bonds.

This would keep a lid on interest rates but weaken the currency.

So it’s bearish for the currency and for bonds, though not necessarily both at the same time.

Impact on equities

An adverse shift in interest rates relative to discounted expectations that’s not offset by a commensurate rise in earnings is also bearish for equities.

Impact on the real economy

Overall, these types of fiscal maneuvers make investors want to get out of the currency and debt and hurts domestic financial assets more broadly, which feeds into the real economy with a lag.

The UK has some reserve status with the pound – about 5 percent of the world’s FX reserves are held in GBP – which means there’s a little bit of a global bias to hold its currency and debt.

So it has some leeway to run fiscal deficits at an elevated level relative to countries with no reserve status.

However, these types of policy errors that lead to a plunge in the value of a country’s currency and bonds are more like those seen in emerging market economies (which has little to no reserve status).

Policymaker constraints – ‘Pushing on a string’

Policymakers cannot spend more money than they’re taking in such that they need to sell a lot of debt that won’t find sufficient demand because it is being sold at low or negative real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. (This phenomenon is often called pushing on a string.)

Implications for policymakers in other countries

If policymakers in other economies choose similar actions, they are vulnerable to similar outcomes.

Even for countries that are in the most privileged position in terms of reserve status (i.e., the US), while they can spend in excess of their income because of this, this is not an unlimited privilege.

The limits to these policies come up in the form of three main constraints:

The UK hit all three of these.

The US hit on two of these with its own stimulative monetary and fiscal policies:

- It saw inflation.

- It saw financial asset bubbles within certain pockets (especially within “emerging tech”).

- It has yet to see currency problems.

Even though the US was late when it came to tightening monetary policy, the speed at which they raised interest rates relative to other developed market economies – growing the US dollar’s interest rate differential relative to other countries’ currencies – created a strong dollar in relative terms.

In the UK’s case, the proposed tax cut was eventually reeled back after the critical market feedback.

Political implications

Had the Bank of England bought gilts more decisively, then the UK tax plan would have been better absorbed. And when the central bank did intervene, the pound went up, not down, so markets didn’t feat that monetizing the country’s debt would lead to a balance of payments crisis.

However, it does mean that there are political limits to fiscal policy, especially during periods of high inflation.

BOE Gov. Andrew Bailey’s interventions were modest because he didn’t want to be viewed as abetting the government. Moreover, given his mandate to bring down inflation, he had an interest in trying to reverse the fiscal path that was being pushed.

In the end, a prime minister is generally easier to remove than a central bank head.

Conclusion

What is the main lesson from the UK bond market spasms?

After lots of debt issuance, fiscal space became limited.

If there’s aggressive debt issuance, markets respond by selling the currency, forcing policymakers to hike more to defend the currency.

But this causes pain in the real economy with the way it reduces credit creation and spending, which represents people’s incomes, so a drop in the currency is generally the path of least resistance.