How Policymakers Are Constrained & What It Means for Traders

Policymakers can get what they want, but only to a point. In this article we’ll explain how policymakers are constrained and what it means for markets.

Where policymakers are constrained

Central banks can do a good job of putting more money and credit into the markets. And, when combined with fiscal policymakers, they’re effective at getting it into the real economy as well.

Namely, they can do well working from the demand side. But from the supply side they’re limited. They don’t physically produce goods and services like in the real economy.

We’ve lived in a world where the problems the Fed faced were problems the Fed can resolve.

And traders and investors have gotten used to that.

In 2008, the problem was that there wasn’t enough credit.

The Fed can turn on the spigots of credit in such a scenario to offset that. It was bold relative to what they’ve done historically, but they’re capable of offsetting credit losses by printing money.

They’re also capable of offsetting income by printing money.

But what they’re not capable of doing is creating the supply that’s normally exchanged for income.

So you’re seeing those types of policymakers constraints.

When to be bullish

For a trader, you’d want to be more bullish on markets when policymakers are free to react to any type of downturn in markets and the economy.

When to be bearish

You’d want to be more bearish when policymakers’ hands are tied and they can only do so much.

We live in a world where we were accustomed to central banks pushing markets higher and providing liquidity on demand, but this may not continue.

The problem is that what used to work for policymakers is now constraining them. People in emerging markets understand the idea of policy room much more than those in developed markets tend to.

Lack of policy room in emerging markets produces inflation and currency issues sooner because they lack international demand for their debt and currency. Few want to save in it so there’s little capacity to push deficits higher.

It used to be that if markets came under duress, you could count on the central bank’s unlimited ability to provide credit. But this isn’t necessarily true forever – they run out of room if they hit various types of constraints (covered in the next section).

Central bankers have done a lot since 2008, and people forget how little liquidity existed back then relative to how it does today.

3 main policymaker constraints

But when they’re constrained, there are three main constraints that can affect policymakers’ ability to step into a problem:

1) When the problem is inflation – when it’s essentially a supply-side problem.

When demand is above supply, they can’t simply step in to solve that because central banks are not the entities that makes the goods and services necessary to resolve that.

A central bank is a type of lender, not a traditional “doer”. When it’s a problem on the supply side, they can’t solve that directly.

2) Currency problems – when lots of new money and credit is created without offsetting supply, that’s a risk for the currency.

Typically you see lots of different assets going up in currency terms – e.g., stocks, real estate, commodities.

In a sense, in accounting terms, they basically act as the inverse of money.

For example, when a house goes up in price even though it’s intrinsically stayed the same, at a microeconomic level it might just be local supply-demand dynamics.

But at a macroeconomic level, if there is lots of new money and credit being created in excess of the supply, that’s a potent factor.

If money and credit goes up in excess of the supply of something that’s wanted, the price goes up.

Such dynamics, however, are bad for bonds because of the inflationary effect. It eats up their real returns.

And it’s bad for cash because more of it is being created.

In emerging markets, there are sometimes cases of hyperinflation. They have problems printing money because the currency collapses in value while they’re trying to print more of it.

The fundamental cause of hyperinflation is in the dynamic of the currency depreciation and the failure of policymakers to close the gap between external spending, external income, and debt service requirements.

3) Asset bubbles are a third type of problem.

When assets rise above their fundamental values and create bubbles, that’s a risk to financial stability if at some point in the future people lose a lot of money because of that.

The central bank is responsible for facilitating credit creation in an economy and therefore responsible for controlling broad-based asset bubbles that occur.

Today, the Fed faces the problem of inflation being well above their target. And the inability to be as easy as they’d like to be because of it.

And asset bubbles are certainly an issue in certain areas, especially in some areas of emerging tech.

There haven’t been outright currency problems yet.

But that puts them in a different type of situation than they were in in 2008.

Tapering to fight inflationary pressure

Tapering asset purchases is valuable to fight inflation, as are standard interest rate hikes.

Both will be effective in pressing down on any unwanted inflationary pressure on the demand side.

There is lots of debt relative to income in developed market economies, so hiking interest rates and tapering asset purchases to give long-term yields freedom to rise will increase debt service requirements and produce less demand in the real economy.

But the only reason they’re going to taper is if the inflationary pressures don’t go away.

But if supply comes online to match the demand and there’s a more deflationary element, then the Fed will slow down. Tapering won’t be as necessary and there’s not as much of a risk to financial markets in such a case.

The problem, more likely, is that the inflation drags the Fed along and that’s risky for traders and investors.

The only reason the Fed is going to tighten is if they have to. That is, if nominal GDP increases at a rate that’s driving inflation higher than they’d like.

If lots of supply comes online to match demand, this is the best scenario for markets. They’re not going to tighten much and will keep policy relatively easy.

Hedging a portfolio in an inflationary or stagflationary environment

In terms of coming up with an inflation playbook or stagflation playbook, you have opportunities.

Most portfolios are not very well prepared for inflation because they’re long a mix of stocks and bonds.

They typically don’t own commodities, which will tend to do well in inflation. This is because they’re either producing the inflation in teh first place because their prices are going up or because of the lack of supply relative to demand.

And both stocks and bonds are likely to suffer in real terms when inflation runs above expectations for an elongated period.

So the goal of an investor during periods of higher inflation and higher nominal GDP is to try to lock in cash flows that approximate the level of growth in the real economy and go short things like interest rates (e.g., Treasury futures, borrowing cash within reasonable levels, shorting eurodollar futures (which approximate fed funds futures)).

But the basic strategy is to arb the difference between nominal GDP and the very low level of interest rates you’re receiving.

For example, if nominal GDP is somewhere between 5-10 percent and the interest rates you’re being given are 0-2 percent, you have a decent spread to capture by going long the former and short the latter.

“Owning nominal GDP” basically means cash flows that correlate well with nominal GDP.

This means their revenue should roughly correlate with nominal GDP but also don’t necessarily have the costs that also vary with inflation.

In other words, their pricing aligns with the inflation pressure and demand in the economy but without having variables costs tied to those pressures.

This can mean companies like consumer staples and other equities that can effectively serve as a store of value, which roughly grow at the rate nominal GDP does. They can also pass along a lot of pricing pressure off to consumers.

The biggest risk is not the cash flows declining over time but rather the interest rates going up.

This is why it makes sense to short interest rates so you can benefit if your spread starts to close.

Most portfolios don’t hedge the main risk.

The main risk is interest rates rising because of the aforementioned factor of inflation. It’s not deflation, because if there’s deflation (e.g., 2008) they’ll stimulate and spend money, which will support the prices of things.

The big risk is stagflation and most portfolios – because of their part-stocks, part-bonds nature – are susceptible under this situation because both underperform in real terms under such an environment.

And part of why portfolios heavy on equities and 60/40 are so popular is because they’ve worked for decades.

So most portfolio managers extrapolate what they’ve become accustomed to even when conditions are changing that make the future likely to be different from what it looked like in the rear-view mirror.

Most portfolios are massively exposed.

And there are ways to hedge the risk by arbitraging the spread between the likely returns available in nominal GDP versus the prevailing level of super-low interest rates.

What does a balanced portfolio look like in this environment?

The basics of a stagflation environment is to be long some assets and be short some assets. That’s step one.

And geographic diversification is still available. The US situation is different from Europe, which is different from emerging markets and China.

Sixty percent of global portfolios are comprised of US assets even though the US is only around 20 percent of the world’s economic activity.

So diversification is undervalued.

Also, the US situation, with its labor issues and being in a type of environment where fiscal and monetary policy have to be coordinated is very different from the type of situation China faces, for example. And are different than the problems Europe faces.

So being diversified geographically and across assets – e.g., having equities exposure, commodities exposure – is a step that everybody can take to deal with the wide range of possible outcomes.

But hasn’t staying in the US been the best option?

Diversification is a common thought in trading and investing to balance the risks and environmental biases that assets intrinsically have.

But having a lot of something is good if it performs well. That’s why people put a lot into certain stocks or cryptocurrencies.

It’s always possible.

But one of the reasons diversification works so well is because people have a bias to go into an asset that’s done well working backwards.

So people have piled into the US because it’s done so well for such a long time.

But the US, today, is an economy with:

- a lot of inflationary pressures

- requires a lot of fiscal policy

- needs the continuation of very low interest rates to prop up asset prices

- paper wealth (i.e., financial claims) is at extremely high levels relative to incomes

- then there are the risks of heightened political conflict

But if you go decade by decade, the best-performing equity markets tend to do the worst the following decade and the worst tend to do better.

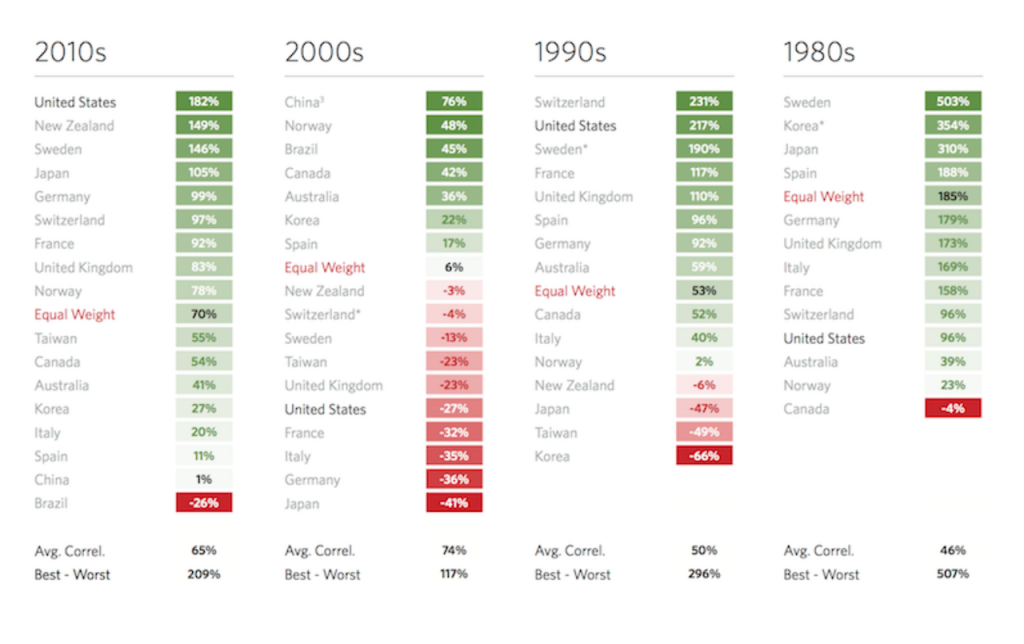

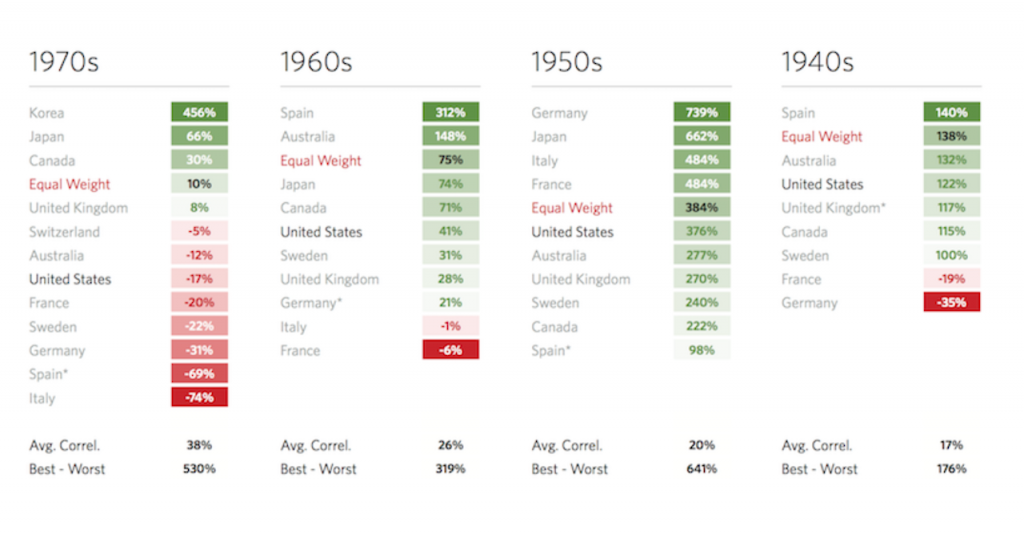

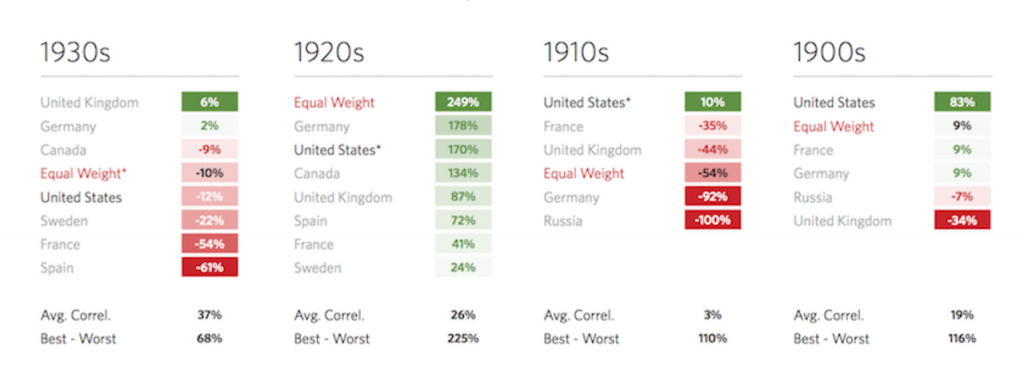

Here are the returns of the various stock markets globally from the 2010s back to the first decade of the 1900s:

Going long underperformers from the previous decade and short overperformers is an overly simplistic strategy and not recommended on its own.

But the general idea is that good performance has a tendency to be extrapolated going forward even when the underlying variables change, which in turn don’t make that forward performance very likely.

The valuations of US (and US technology, in particular) are fairly extreme relative to other markets.

For example, Chinese equities – holding earnings constant – are priced at about 60 percent of the levels of US assets.

This reflects concerns over China’s regulatory regime and themes like Common Prosperity. In this case, shareholders can’t be sure if the earnings are ultimately going to be their money or if some (or a lot) of it is going to go toward trying to achieve the Communist Party’s social, political, and economic goals.

Not only does the US have to massively outperform economically, it’s going to have to perform even better than it has over the last decade based on what the pricing shows.

At the same time, maybe the US dominates and global portfolios go from 60 percent US assets to 70 percent or more.

There’s a wide range of outcomes.

But more likely, over decades, you go from 60 percent to something that’s more in line with the US’s relevance in the world (closer to the 20 percent).

China’s investability

Over periods of time, traders and investors get some amount of negative news flow out of China.

Regulation is a concern in China. It even, for many, calls into question China’s overall investability.

How do you approach China?

So, a couple things, in particular:

a) Everybody looks at the equity market.

But there’s more to markets than just the stock market. A balanced mix of assets including Chinese equities, bonds and credit, and commodities is going to usually do okay even if one or two of those parts is down. Assets all act differently based on their environmental biases.

And China doesn’t have the super-low yields that are impacting the returns of developed markets.

Stocks have had their issues at times because policymakers are looking to balance different goals at the same time.

There’s ‘Common Prosperity’ as mentioned. The Chinese system is based on “dialectical materialism” – with modern roots in the teachings of Marx and Lenin. Their main focus is on growing the pie and dividing it well.

China has a lot of state-run companies. But the overall level of capitalism is about the same as in the US. For example, the US has higher tax rates than China even though the US is commonly thought of as being a more pure capitalist system.

China’s current economic model is really more Confucian than anything – namely, more like a top-down society run in a similar way to how a private company might be operated.

There are “wise leaders” at the top making the decisions, then there’s everyone beneath them knowing their role in society and carrying it out in the interests of the whole.

China also regulates things like information security and ensures that no company becomes more important than the Party.

b) China also has goals of becoming a global superpower.

For that to happen, they recognize the need to have well-developed capital markets.

History shows that every global power has had a leading financial center. For example, if we look at the last three leading global empires:

- Amsterdam in the 1600s and 1700s

- London in the late-1700s through the 1900s

- New York in the 1900s to the present

All became the world’s top financial center. Cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen are developing in that role.

China is moving toward a more open financial system. The policy direction is in place. It’s how the country gets from where it is now to where they want it to be that matters.

How you think about China might also depend on how long your time horizon is. Over the past 30 years, China’s economic results have been remarkable. But over any given year, the results will vary.

Trends or bumps in the road?

Every once in a while, whether it’s 2015 or in 2021, the financial market development will take a step back as they try to achieve some other goal.

But the overarching trends over the course of decades has been the development of these markets.

They’re now at a level of having the second-largest capital markets globally and are serious competitors to the US.

And the world remains underinvested in them and under-owns its currency, the renminbi, relative to China’s relevance in the world (close to 20 percent of global GDP and growing).

The balance of assets

China’s capital markets function well, as evidenced by the fact that the balance of assets works about as well as it has in other countries.

The stock-bond correlation is negative as it has been in the US over the course of decades. This means drops in stocks tend to be made up for by gains in bonds, for example, in a more predictable way.

In fact, it’s more reliable today than it is today in the US and Europe because interest rates are at a more normal level.

Regulatory risk

There is regulatory risk in China because they’re mostly focused on building. The rule of law setup isn’t as developed as it is in more established markets.

They’re essentially coming up with the laws on the fly and they don’t have a structure for how to deal with companies and the various things related to governing them.

That creates a more volatile environment for investors. But a lot of that is priced in. As mentioned earlier in the article, you get maybe a 40-45 percent discount in China’s markets comparing dollar for dollar.

Should the “discount” be better or worse?

It’s hard to say, but as a whole, you’re probably better off erring on the side of diversification rather than being in only one market or the other.

And that mix of assets between the two markets doesn’t have to be in just equities. It can be in other types of investments outside stocks.

Will China become the largest global economy?

Some are even skeptical that China will have the largest global economy at some point in the future. But China’s incomes (GDP per capita) are going to grow faster than those in the US.

As an emerging power, China still has a lot of catching up to do to get its living standards on par with the US or at least other developed markets.

But even if China’s incomes only get to half the level of those in the US, there are four times as many Chinese as Americans, so that means their economy would be twice as big.

And whoever has the most dominant economy and technology tends to be superior in most other ways (e.g., militarily, geopolitically, reserve currency).

Competition between the US and China and impact on markets

Policymakers from both the US and China are increasingly taking a more hawkish approach toward each other.

While much was made of the “trade war” during the Trump administration, the Biden administration essentially continued the same policies, as expected. No tariffs were rolled back, among other measures put into place during the Trump years.

The less collaborative working environment is a net drag to both economies and markets.

The trade frictions forced China to focus more on developing its own internal consumer markets – that is, something they were already doing, but something they had to pull forward and expedite.

And the more combative relationship means there’s less shared between the two economies.

Supply chains are more separate. Technological development is done independently.

There’s less of a “how can we help each other?” type of mentality to help grow productivity together. And there’s more of a recognition that the two are global competitors butting up against each other.

And not that it was all collaborative before or all competitive. But on the continuum it’s heading toward more competition.

Economically and financially there’s a lot that’s unknown, which is an argument in favor of diversifying in terms of how that competition is ultimately going to play out.

Hopefully the level of competition won’t boil over to the point of an actual hot war, but it’s a competitive situation that’s going to change things a lot.

When production demand soared in China and it couldn’t meet that demand, that’s something that hit the entire world with a lack of goods supplied to other markets.

It’s not only China that will suffer the financial consequences of those challenges.

And when Chinese policymakers openly say that they want to slow down US innovation, that sounds bad, but that’s more or less a reflection of what’s already known.

It’s a reality that China and the US are going to increasingly split up in various ways.

And it’s a big deal in terms of managing a portfolio when it comes to how all that might play out.

For example, what if there’s a military engagement? What if supply chains that are highly integrated between China and the US get broken up?

Who’s going to benefit and who’s going to suffer in terms of all the things that are going to be thrown at your portfolio?

There’s a lot that’s unknowable

But the best tool to deal with that wide range is to not take a lopsided bet on one market or the other – e.g., being great for the US and bad for China or vice versa.

A good approach is to set yourself up a broad range of how things can play out.

Markets compete for capital and that always circulates around between different assets, different asset classes, different countries, different currencies, and different financial and non-financial stores of value.

It’s prudent to diversify as to how that competition is going to play out and how the demand for goods will be allocated.

If things go unexpectedly in one direction or another, you’re still prepared for whatever outcome actually happens.

Things change in unpredictable ways and you can never be too sure.

The way most approach trading is “how much can I gain?” – rather than what could happen and how far could it go?

Traders trying to make easy money often place one-way bets where they feel like the odds are in their favor, but it’s a very risky approach.

Conclusion

In this article, we covered how policymakers are constrained and how this affects traders. Inflation has been rising and most portfolios aren’t prepared for it.

Inflation is the most immediate way policymakers are constrained when demand runs into supply constraints.

Inflation means that demand or spending is above the supply or productive capacity of an economy. It typically leads to problems like:

- asset bubbles

- currency problems (because the interest rate isn’t sufficient enough to offset the loss in real value)

- credit problems

While it’s important to keep demand up, eventually there’s a lot of pressure on policymakers from consumers and businesses who are losing out if their wages and revenue aren’t going up much but prices are going up a lot – whether through cyclical forces or policy excesses.

If inflation hits consistently above-target and stays stubbornly high, central banks will need to reverse course on their stimulative policy measures.

So you could see even pressure on asset prices. This would be particularly bad for riskier, rate-sensitive sectors like tech.

This is because lower interest rates mean these companies can issue new equity or debt at very low costs to grow their businesses. But the cost of borrowing goes up with higher interest rates, which helps dry up some of their capital access.

Traders are used to policymakers getting what they want because it’s easy to create demand. But supply shortfalls that mix with high demand to create inflation is a different story. Policymakers are constrained when these forces are working against them.

Certain strategies like going long companies that will correlate with nominal GDP and shorting rates is one option for traders looking to benefit.

Geographic diversification is another, as different parts of the world are in different circumstances.