Inflation Protection: Asset Allocation in a Rising Inflation Environment

The basic idea behind the merging of fiscal and monetary policy is to get the inflation rate up in an economy. The basic premise driving asset allocation in a rising inflation environment is that assets with fixed returns get squeezed and become less attractive. Other types of assets are needed to provide inflation protection.

Let’s say cash earns 3 percent nominal in a normal environment and inflation is 2 percent.

That means your real return is one percent, taking the difference between the two. That’s not a lot, but you know that you’ll at least preserve your wealth in cash plus earn a small spread assuming inflation remains under the nominal return or if the nominal return increases.

However, when interest rates hit zero for cash and close down to those levels for nominal rate bonds, that puts asset allocators in a quagmire.

Central banks will always target a somewhat positive inflation rate. So zero percent cash and bonds (or negative in some jurisdictions) face negative real returns – i.e., nominal returns minus inflation.

The entire idea of putting your money to work in trading, investing, or in any business pursuit is to get more money back in return.

Real returns are important to consider. Returns are not just nominal returns; there’s the additional component of the currency’s value.

The value of nominal dollars or any nominal monetary amount decreases over time because of inflation.

You can make five percent nominal, but if the value of the money those returns are denominated in are declining by an equal amount each year – i.e., a five percent inflation rate – no real wealth is being created. If inflation exceeds the nominal return, then wealth (spending power) is being destroyed.

Unifying fiscal and monetary policy

When cash and bonds rates are at or about zero, traditional monetary policy has lost its stimulative capacity. More of the burden for stimulating the economy moves toward fiscal policy with the central bank backstopping those measures.

This means more money creation, which in turn makes cash unattractive. They’re printing a lot of it and the real yield on it is low – i.e., the nominal yield is less than the rate of inflation.

Cash is a source of wealth destruction. That also spreads to bonds, which locks in the terrible real returns.

It can also spread to stocks. A negative real yield on stocks occurs when inflation is higher than the inverse of the P/E ratio.

If the P/E ratio is 30x in a select basket of stocks, that means it takes 30 years to make your money back based on the current price relative to the estimated forward year’s earnings.

The inverse of that earnings ratio is just the yield or return. One divided by 30 is about 3.3 percent.

If inflation is higher than that 3.3 percent, the stock(s) has a negative real return.

S&P 500 vs. Real Earnings Yield

If you’re a trader or investor, you have to be concerned about the idea of holding any asset that yields negatively in real terms.

It’s especially true when you’re hanging out in an asset class that’s as volatile as equities are.

So, it’s possible for cash, bonds, and stocks to be bad at the same time.

That’s why stocks tend to react negatively to higher-than-expected inflation readings.

It reduces their real yields. Moreover, it can increase the probability of interest rate hikes by central banks. That makes cash scarcer and a higher yielding asset, and reduces the availability of credit. It creates competition for riskier assets.

So, you generally don’t want to hold assets that yield negatively, whether that means cash, bonds, or even potentially equities.

Moreover, when rates are very low, the duration of assets is very long, which makes them more sensitive to changes in rates. A reversal of the low rate regime is most likely when inflation runs above expectations and there’s a lot of excess price pressure in the real economy.

Deficits and addiction to negative real rates make alternative stores of value good to own

When a country is running deficits (trade and/or fiscal) and offering negative real rates on their debt and liabilities to keep everything going, alternative wealth store-holds are increasingly attractive.

It also causes problems for the country doing these things because negative real yields signal holding your wealth in these things causes wealth destruction.

The incentives of those in government have a lot to do with the chronically indebted environment.

Most people pay attention to what they can get and pay much less attention to where the money will come from to pay for it all (productivity). Accordingly, there are strong incentives from elected leaders to spend a lot of borrowed money and make a lot of promises to give voters what they want and to take on debt and other forms of liabilities that will cause problems going forward.

Inflation protection assets: Considering your options

International markets

First, recognize that not all of the world is the US or developed markets.

Some emerging markets are a possibility, such as Southeast Asia, where they have a normal interest rate, normal yield curve, and normal return on assets.

While cash and nominal rate bonds might be bad in developed markets where they have intractable problems, they’re not bad everywhere.

So if deflation were to win out, holding the bonds of certain emerging market countries could be prudent to capture those shifts.

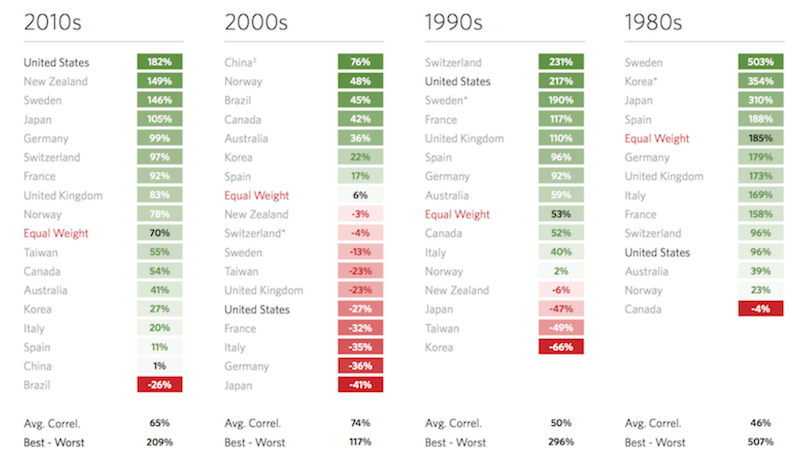

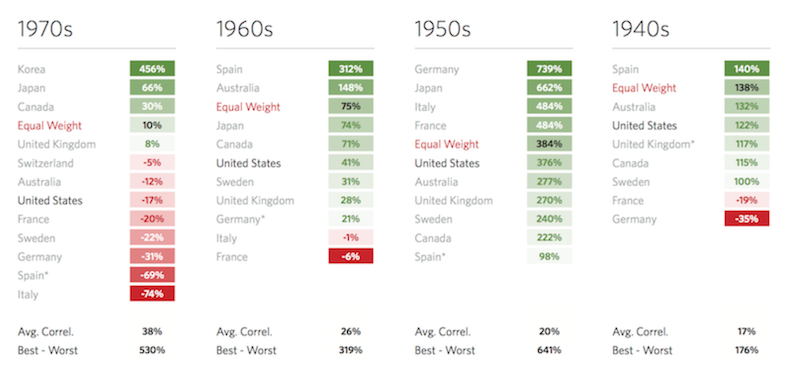

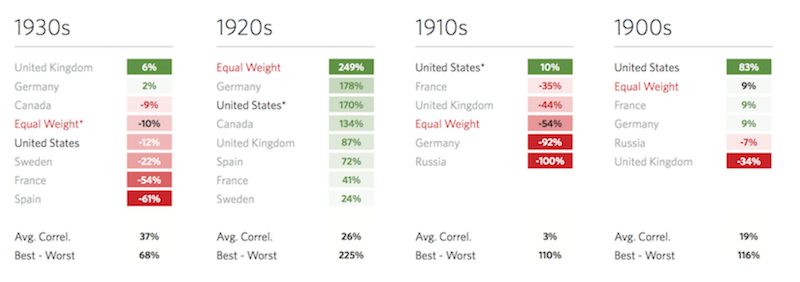

Global diversification

Global diversification is insufficiently valued. Capital is always shifting around. It’s always moving between assets, different asset classes, into different countries, and into different currencies and things that are of a financial and non-financial character.

Sometimes a globally diversified portfolio doesn’t work as well when one country has been dominant.

For example, the US has been a pretty dominant market in most people’s lifetimes.

But whatever country is good, going decade by decade, tends to be a lower-performer in the 10-year period following.

You can look at the patterns between each country and the equal weight portfolio.

There’s generally always rotation. Extrapolation happens even when the underlying conditions don’t support a continuation.

Sometimes things transpire in a way that make their returns good when looking in the rear-view mirror, but likely to be quite bad when looking forward due to the nature of how lowering interest rates and other forms of stimulus (money printing, currency devaluation) works.

Who will benefit from a growth surge but less liquidity?

The US spent the 2010s and part of the 2020s benefiting from lots of liquidity.

Those policies have a limit and most US assets have benefited from them greatly while they don’t have as much cyclical variability to nominal GDP growth as the assets in emerging markets.

So, naturally this might push you toward a more global diversification.

Assets that are likely to benefit include assets in the countries running tighter fiscal and monetary policies that ensure a sound currency and a safe balance of payments situation.

In the end, each entity – individual, corporation, government – must earn more than its expenses and have assets above its liabilities to remain sustainable.

Environmental diversification

Are you prepared to deal with an environment that may be less favorable toward stocks or a more stocks-centric portfolio (e.g., 60/40 stocks/bonds)?

All assets have environmental biases. Stocks tend to do well in an environment where growth comes in above expectation and inflation is low to moderate.

If you have a bond part to your portfolio (namely, safe government bonds), those benefit when growth and inflation are weak.

If inflation rears up and stocks flounder, do you have enough assets to help offset that. Cash and bonds aren’t likely to do you much good in a stagflation environment either.

If inflation picks up, the real yield of cash gets lower and the value of money (cash) goes down.

For bonds, it’s the same thing. Bonds are a promise to deliver money over time. Inflation is also likely to impact their prices. Higher inflation causes nominal yields to rise, which reduces their prices. If not, then it reduces their real yields.

Inflation is bad either way for fixed-rate investments.

Bonds tend to diversify well with respect to growth. When pro-growth assets like stocks falter when discounted growth goes down, a lot of those flows go into bonds.

But bonds don’t diversify stocks well with respect to higher inflation stocks. The fairly reliable negative stock-bond correlation isn’t likely to hold up when inflation rises.

Stagflation or inflation protection assets

This is where things like commodities, precious metals, some inflation-linked bonds, other currencies (of countries without the endemic financial issues), and other stores of value can potentially perform well.

Do you have enough of these “higher inflation” or “stagflation” assets to help protect a portfolio?

By and large, most market participants don’t have enough. It’s largely because they haven’t experienced such an environment before.

That favors alternatives such as:

- Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

- Gold and other forms of precious metals (e.g., silver, palladium)

- Commodities (industrial, agricultural/soft)

- Other countries with more normal cash and nominal bond rates

- Stocks that can act as a type of bond replacement (e.g., consumer staples)

- Private businesses that aren’t overly cyclical or could benefit in a higher inflation environment

- Collectibles

- Riskier ventures where there’s a higher prospective return (startups, angel investing, venture capital)

- Alternative asset classes like cryptocurrencies and DeFi instruments

An institutional allocator will need to have something that’s tried and true like gold, industrial commodities, commodity producers, various forms of land (timber, farmland, other forms of real estate), collectibles with large markets, EM FX, inflation-linked bonds, and other traditional stuff.

Collectibles are not commonly thought of as a source of inflation protection because they’re not traditional financial assets.

That can include things like art, which is more traditional, or something like classic cars. It can also get more into niche type of things. There are such things like rare wine, whiskey or other liquor forms, dinosaur fossils, baseball and other forms of trading cards, or something newer like NFTs or other forms of digitized assets.

Smaller investors can be more nimble in terms of what types of things they can buy. For example, a hedge fund is probably not very likely to buy dinosaur fossils because they have a limited market and therefore a limited capacity to allocate capital toward.

There’s not a multi-billion dollar market for them (and similar types of items) to our knowledge. Certainly, the most conservative investment vehicles, like pension funds or central banks, aren’t going to buy things like that.

Many hedge funds may be able to buy an inflation swap (a type of derivative) directly as part of their inflation protection strategy, as it’s the purest form of hedging against inflation.

Whatever it is, it needs to be reliable and needs to be able to be done at scale for an institutional manager.

It all boils down to what’s a reliable store of value.

In this respect, there is no one answer. It’s not only gold or silver, or traditional long-duration alternative currencies. It’s not just other types of commodities. Or real estate. Or cryptocurrencies.

It has to be a diversified answer.

So the big two asset allocation ideas for dealing with inflation are:

i) Global diversification to different countries and currencies, and

ii) Environmental diversification in scenarios where inflation runs higher than expectations and policymakers get in a delicate trade-off between accepting higher inflation or hurting economic growth if they tighten policy.

A subset of environmental diversification is owning enough inflation or stagflation assets to help successfully get a portfolio through environments where inflation runs above expectations and harms traditional asset classes like stocks and bonds.

Shifting policy doesn’t mean abandoning certain things altogether

The idea is not necessarily to abandon the traditional assets entirely. What moves markets is how conditions change relative to what’s discounted in the price. All that’s known is discounted in.

Inflation is not a 0-or-1 thing. Exchange rate variations feed into inflation. For example, if one country’s currency depreciates relative to another, that’s inflationary for the depreciating country and deflationary for the appreciating country.

A lower value of one’s currency means money doesn’t go as far. Exports become cheaper for the country that sees its exchange rate appreciate relative to your own. Imports also become more expensive, which means higher prices, holding all else equal.

So ultimately, it’s not clear whether inflation or deflation will win out relative to expectations.

It’s all about whether you have enough assets to withstand a higher inflationary environment that can be so damaging to the traditional portfolio that has an equity-centric allocation.

That doesn’t mean giving up on cash or bonds or stocks or anything that’s expensive in developed markets because of where policy is – super low short and long rates on the monetary side plus aggressive monetization through fiscal channels.

Deflationary forces can still win out if certain things transpire – e.g., less willingness to print, another downturn in the economy – but it does mean that there are material risks to holding them in any type of concentrated way.

Longer duration bonds are especially a risk when the central bank is encountering inflation and it wants to taper to cut down on that. The trade-off is that the Fed is already buying around half of all bond issuance – due to a lack of private buyers – so it can become hard to fill that demand.

Demand flooding into unexpected places

Sometimes the demand under easy monetary and fiscal policy goes into unexpected places.

With new wealth from things like cryptocurrency or tech companies, a lot of that wealth goes into the things that the beneficiaries of these price moves want to buy.

In other words, they want to convert some of that new wealth into something real. New buyers come into the market and give cash to those who either originally produced them or were an earlier participant/holder in the market and want to do something with that money.

That can be housing, which is a classic case of where wealth is spent because shelter is a basic need. It can also be a type of luxury purchase. People spend a lot of time in their homes and it can be a status symbol, so new wealth aided by easy money policies tends to help the top of the housing market.

It can be things like baseball cards or even new things like NFTs and other digital assets. Or collectibles like ancient artifacts. Collector sneakers. The list goes on.

When there is so much money in financial assets it will want to seek out a home in something.

A risk for policymakers is that flooding the financial system with money causes those asset prices to go up and the risk premiums to compress to such a level that the money wants to leave the country to find better returns.

The short-run effects of easy monetary and fiscal policies are the stimulative impact it creates first on asset prices (greater aggregate wealth) and then the feed-through into the real economy.

But the trade-offs are stretched asset valuations and bubbles in one or more pockets of the economy and asset markets, and/or excess real economy price pressures that have to be reined in.

Capital outflow is a concern.