How to Trade Emerging Markets (Part I)

This article is the first in a series of how to trade emerging markets. It covers the common characteristics of how emerging markets progress financially and economically. For those who do trade actively and especially those who trade over longer time horizons, understanding what part of the cycle you’re in is important.

In our last article, How Empires Rise and Fall, we covered a template of how countries, nation-states, and empires go through boom and bust periods throughout time, and what the general features are of each of the broad five stages.

While financial markets change and monetary systems change, throughout history, the same things happen over and over again for the same cause and effect reasons.

The types of debt crises that emerging markets go through tend to be different from the ones that developed countries go through.

Debt crises in developed countries

The debt crises in developed markets tend to be deflationary (e.g., the Great Depression in most parts of the world in the 1930s, 2008 financial crisis) because they heavily borrow in their own currency. The crisis creates a hole in the economy by hitting incomes and balance sheets (i.e., worsening debt to income ratios). This hits the prices of financial assets and feeds through into the economy, causing prices to go down (i.e., deflation).

Debt crises in emerging countries

When emerging markets borrow, they often heavily do so in a foreign currency. This is because reserve currencies have lower interest rates, limiting the debt burden, and there’s typically limited demand for their own currency.

When they earn income in domestic currency and the crisis comes, that incomes goes down. Moreover, their currency, less demanded as the reserve currencies they typically borrow in, goes down in relation.

So, their debt burdens (in the appreciated foreign currency) increase while their income (in the depreciated domestic currency) declines. The currency declines make imports more expensive and pushes up inflation.

Citizens and investors also want to get their money out of the country, which also fuels the inflation process and inflation psychology.

While it is well-known that central banks manage monetary policy in a way to balance output and inflation, it is not as well-known that it is easier to achieve higher output per each unit of inflation when capital is flowing into the country and harder to achieve when capital is flowing out of the country. When capital is flowing out, the trade-off between growth and inflation is much more acute. Easing policy under these circumstances creates more inflation than desired while tightening policy is too onerous in terms of its effects on growth.

When emerging market crises become unmanageable (e.g., runaway inflation)

Hyperinflation occurs when investors holding money and credit assets (like bonds) want to sell them and move their money into other assets or to other countries.

As this selling occurs, the central bank is in a position of having to choose between interest rates increasing (which is not desired because it reduces money and credit creation) or creating money and buying financial assets (which devalues money and credit assets).

When they need to create a lot of money and can’t close the gap – the money keeps being moved out of the country and into inflation-hedge assets – this monetary inflation becomes a hyperinflation.

The currency becomes worthless, as do bonds (which are a promise to deliver currency over time). Stocks don’t provide an adequate hedge as they lose value in real terms.

Gold, and some other commodities, become the asset of choice. Alternative payments systems, like cryptocurrencies and other forms of digital currencies, are also viewed by some as viable monetary stores of wealth, or at least a temporary improvement for those undergoing runaway inflation conditions, such as the recent cases of Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

Part I

But let’s back up a second and we’ll cover each individual stage in more detail one part at a time.

We’ll cover the first part of the cycle and its characteristics as it pertains to emerging markets, or generally any country that does not have a reserve currency. (The main reserve currencies are USD, EUR, JPY, GBP, CAD, CHF, AUD, and NZD. The Chinese yuan (CNY), also known as the renminbi (RMB), could also qualify and China also borrows predominantly in its own currency, which helps it manage crises that it goes through.)

No two cycles are exactly the same. But if you study enough of them and/or go through enough of them as an investor, you’ll get the hang of the general characteristics and a playbook for what to do, just as a mechanic determining what’s wrong with a piece of machinery or a doctor watching the progression of a disease.

Stage I: The Early Cycle Upswing

The foundation

First, there needs to be some basic foundations in place to attract external capital and create domestic wealth broadly.

For example:

– Is the country politically stable?

– Is corruption low?

– Is there rule of law?

– Are private property rights respected?

– What is the overall culture of the country? Is there a focus on work over leisure? Is commercialism and innovation viewed favorably?

– What is the regulatory and bureaucratic environment like? Is it too lenient, is it fair and appropriate, or does it stifle business activity?

Many investment firms will develop indices to quantify how each country comes in across cultural, value, and indebtedness metrics.

Only when these are in place to a sufficient enough degree will investors have enough confidence that the positive “vital signs” that characterize each jurisdiction could create a hospitable investment environment.

The financial and economic rise

With that out of the way, we’ll go through these below.

When countries are first coming up in the world, the country’s labor is cheap. Therefore, they are competitive and ripe for productive investment opportunities.

Because their incomes and savings up to this point have been low, few have been willing to lend to them and private sector lending is low.

Accordingly, debt levels are low and their balance sheets are in good shape.

Countries in this stage usually move from sustainable living lifestyles and adopt an export-oriented economic model – selling resources and/or selling low-value-added goods to richer countries.

This attracts foreign capital inflows. This helps fund investments, which produce quality returns.

Capital flows are important to monitor because they are volatile and therefore have a material effect on asset prices (in comparison to something like productivity, which matters a lot in the long-run but doesn’t cause much volatility in economic activity or in asset prices in the short-run).

As countries begin this upswing, incomes rise and debt begins to rise at a similar rate. Their debt and equity markets begin to develop and benefit. This encourages more investors to buy in. Buying financial assets on leverage to improve returns becomes increasingly common.

Because of these conditions, banks and the private sector begin borrowing, as does the government. This is sensible because their incomes are increasing and debts can be more easily serviced.

The strong fundamental backdrop and leveraging up of the economy set up rising asset markets, which helps fuel more capital inflows and an overall “boom”. Foreign investors will typically want to invest in companies that can produce goods cheaply and export to markets that will earn them a good return.

And because the country’s asset markets are improving in stature, the demand for the currency rises.

If a country sells more from other countries than it owes to them and/or there are capital inflows (from attractive investment opportunities to foreigners) – i.e., a positive balance of payments – then the demand for its currency will be greater than its supply.

In turn, this is positive for the country’s central bank. When capital inflows are positive, they can get more output per unit of inflation. This is because these positive inflows can be used to increase foreign exchange reserves, lower interest rates, and/or appreciate the currency, depending on how the central bank chooses to use this advantage. (The opposite, capital outflows, has the reverse effect and makes the trade-off between growth and inflation more difficult to manage.)

During these times of nascent currency strength, some monetary policymakers will choose to enter the foreign exchange market to sell their own currency for the foreign currency coming in (usually from foreigners buying their goods in the export market).

They do this to prevent the currency from rising, as this can have adverse economic effects, such as decreasing their competitiveness in the international export market (i.e., goods are more expensive) or because of how a higher currency can squeeze some debtors because their obligations denominated in that currency become expensive.

When the central bank exchanges its own currency for foreign currency, it needs to do something with this newly acquired currency. They will take it and buy financial assets denominated in that foreign currency – usually governments bonds. These bonds get put into an account that economists and investors call foreign exchange reserves.

Foreign exchange reserves are like what savings are to an individual.

For countries, they can be used to buy investment assets for the prospect of quality investment returns or for strategic reasons.

FX reserves can also be used to smooth out fluctuations in the foreign exchange markets by reconciling any imbalance between foreign currency demanded and that supplied by the free market.

Stability in a currency helps improve the desire to hold it, which helps its reserve status. Currencies serve a use as a means of exchange and a store of wealth. More stable assets are better stores of wealth.

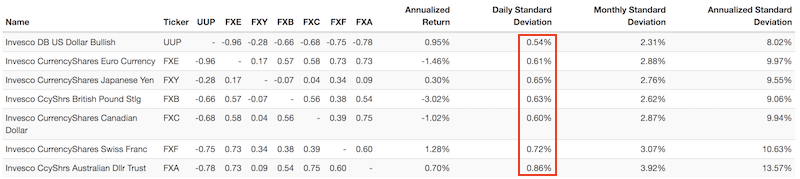

As shown within the diagram below, the US dollar (USD) is less volatile than the other main reserve currencies globally, which improves global trust in its status as a wealth store-hold.

(Source: Portfolio Visualizer)

Since the accumulation of FX reserves involves the selling of their own currency for foreign currency, it helps to avoid the upward appreciation on their own currency. This helps maintain better competitiveness internationally and therefore can add more growth (and money) to the domestic economy. Moreover, the creation of new currency to buy the foreign currency (controlled by the central bank) increases the amount of overall domestic funds available to lend out or to buy assets (and therefore causing asset prices to rise).

During this phase, the currency’s return is good because either:

– the central bank will increase the money supply by creating money and selling it for foreign currency, which will cause the country’s assets to increase in price when measured in domestic currency terms, or

– those who want to be part of the country’s asset markets will need to sell their own currency for the domestic currency

Accordingly, over this time where there’s a positive balance of payments situation, there’s a net inflow of capital, which causes the currency to appreciate and/or lead foreign exchange reserves to increase.

These positive inflows are stimulative to the economy. This helps improve the monetary management of the economy, and cause the country’s asset markets to rise.

Foreign investors have two pieces to the puzzle to monitor:

– their investments in the country, and

– their currency returns (which they sometimes hedge out)

During this phase, investors will make money through a combination of asset price appreciation and/or currency changes. As previously mentioned, there is a trade-off between currency appreciation (e.g., makes exports less competitive on the international market) and asset prices. The more the currency appreciates, the less assets will appreciate, and vice versa.

Conclusion

During this early upswing phase, the country is in a healthy state monetarily. They go from more sustainable living situations to one where they want to compete in the world and export their goods and/or resources to wealthier countries.

Incomes rise and debts generally rise in conjunction or below the pace of income growth. They become wealthier and their balance sheets remain healthy. It’s generally a quality environment for investors in the country’s debt and equity markets.

This period of strong economic conditions, strong capital flows, and strong asset returns leads a virtuous self-perpetuating cycle.

But this leads us to the next part of the cycle, which we’ll cover as this series continues.