Tapering: The Trading Playbook

Tapering is the process of a central bank reducing its ownership of financial assets. It is sometimes called quantitative tightening (QT) or “rolling off its balance sheet”.

First, we’ll start with an overview of the circumstances behind tapering’s role in economic management (monetary policy).

Then we’ll move into the big picture forces of what major economies face and how tapering plays into those.

And then we’ll cover what tapering means for portfolio construction.

Tapering overview

During the 2008 and 2020 crises, the US Federal Reserve and other central banks reduced interest rates to get more money and credit into the system.

Lowering interest rates to zero wasn’t enough. So they turned to buying financial assets (mostly their own sovereign bonds) to lower long-term interest rates.

A central bank “printing” money (electronic money creation) and buying its own assets is debt monetization. Because that sounds scary and/or controversial, the term that’s popularly used is quantitative easing, or QE.

When a central bank buys its own debt, this puts this newly created cash in the hands of the holders of that debt. They then can use it for three basic purposes:

- Savings

- Spending

- Purchases of other financial assets

Naturally, the entity that just sold the asset in exchange for cash is going to be most motivated to want to buy something similar to what they just owned.

That might mean owning a bond of a slightly longer duration bond or an asset of slightly higher risk.

They’re less likely to buy goods and services with it, which provides income to the sellers of those things in the real economy.

So the trickle-down effect of QE into the real economy isn’t much. It’s very indirect. It generally takes a large amount of QE to see much impact in the real economy.

Morevoer, QE is most effective when spreads between short-term and long-term interest rates are wide and liquidity is tight.

When long-term interest rates also start to bend down close to zero, QE is no longer that effective and central banks will need to go into alternative policy forms.

Overall, the period of a central bank being stimulative in this way is good for all kinds of financial assets, especially risk assets.

Sometimes, if a crisis is bad enough, the central bank will not only buy its own debt, but also buy the debt of corporations and potentially even stocks and other risk assets as well.

When an economy improves enough, tapering enters the equation

When an economy is improving – jobs are being filled, unemployment is decreasing, actual GDP is nearing potential GDP, and inflation is starting to pick up – the central bank will think about tapering its purchases of financial assets.

At the same, tapering may be difficult for central banks because the fiscal governments run deficits and there may not be enough free-market demand for the debt.

Example

To illustrate, let’s say a fiscal government is running a deficit of $1 trillion per year.

When there’s a $1 trillion deficit, that means it needs to be plugged by issuing debt. So they issue $1 trillion of bonds each year.

Say the free market – private entities (e.g., commercial banks, institutional investors, corporations, individuals, etc.) and foreign governments – have enough demand to buy $400 billion of that $1 trillion.

That means there’s a $600 billion demand shortfall per year. So, the central bank has to buy up the rest unless it wants yields to rise.

Since higher yields feed through into higher borrowing costs, which can lead to lower credit creation and create an economic slowdown, the central bank calculates that it needs to buy $50 billion worth of bonds per month ($600 billion divided by 12).

But as the economy improves, it finds that the fiscal government’s tax collection improves from higher incomes and asset values and more people returning to work. The government’s spending also decreases due to fewer support payments needed.

Now it calculates that the deficit will be reduced from $1 trillion to $500 billion per year.

And because bond yields generally rise as an economy improves, there’s more incentive to hold that debt holding all else equal.

So instead of free-market demand of just $400 billion, there’s now demand for the full $500 billion of debt issued by the government that year.

That means the central bank can reduce its support to balance the market and begin buying fewer and fewer bonds.

In fact, if projections turn out to be correct, it can reduce its purchases to zero and even sell off bonds from its portfolio if there’s enough free-market demand for them.

This process is called tapering.

The real world

However, unlike the stylized example we just went through, developed market central banks are going to have a very hard time tapering bond purchases.

Tapering – while central banks often talk a lot about in the lead up – won’t be much of a taper at all. There’s not enough free-market demand for the bonds they’re issuing relative to the supply.

Deficits are still bloated

First, the deficits remain bad.

Even if crisis-related support payments to households, businesses, and local governments can be curtailed, more money is progressively needed for pensions, healthcare, and related insurance obligations.

This is a progressive squeeze over time.

Politicians will want to hike taxes and create more types of them. When there are large holes to fill they’ll always want more money out of the private sector.

However, this has impacts on the types of decisions people make. There are arbitrage effects and movements of capital.

The US is in the classic state of its development where the costs of maintaining the overall empire are more than the revenue it brings in.

This period is typically characterized by more class conflict – classically and most prominently between the rich and the poor, and the political left and political right – over how to divide wealth and political power.

But the overarching forces are most important.

When the British empire went through its relative decline, there was no group of people they could have feasibly extracted more money out of to arrest that process. The same was true of the Dutch empire before that.

To get more wealth there needs to fundamentally be more productivity and it’s not easy to get the productivity rates up.

So, there’s still a need to create debt.

And when domestic economic conditions are weak and the central bank or monetary authority needs to buy a lot of this debt, it means the debt yields negatively in real terms. There’s not the incentive to hold it.

This means the central bank is in a bad spot.

It can’t go to zero purchases if there’s a shortfall in demand for the debt, or significantly cut purchases without driving rates up.

And the low interest rates are also what helps hold the market for risk assets together. And at a point, if you let asset prices slide, you get a negative feed-through into the real economy.

So they can’t get the rates up much because it doesn’t take a lot to get the debt servicing to swamp the amount of income being produced.

They have a trade-off between higher inflation (keeping rates lower) and lower asset prices (hiking rates faster than what’s discounted in). It’s not an easy balance to get right.

And when rates are lower the duration of financial assets lengthens. This makes them more sensitive to changes in the term structure of interest rates.

The tapering trading playbook

Trading and investing isn’t easy because it’s not how things transpire; it’s how they transpire relative to what’s already discounted into markets.

If a central bank is starting to taper, you will have needed to anticipate how to handle this ahead of time.

As you might imagine, when a central bank is stimulative, this is great for most asset prices.

Generally speaking, it’s good for stocks, gold, commodities, and real estate.

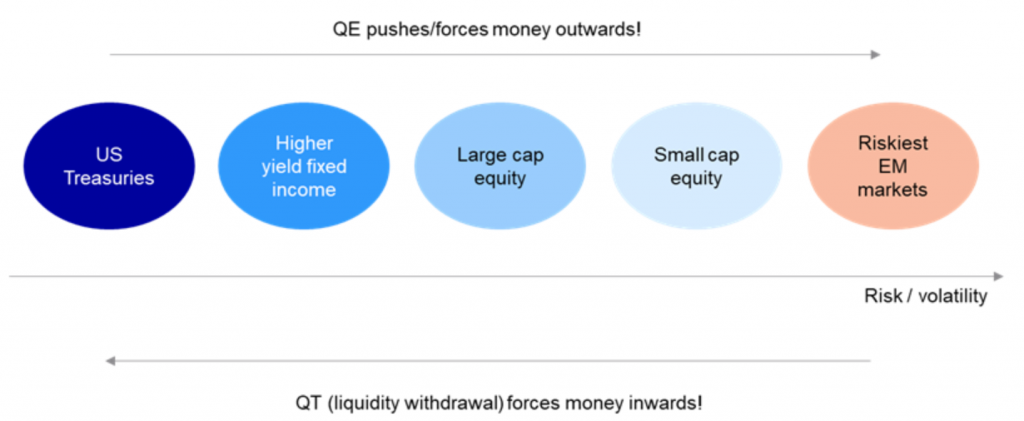

When QE is running on full steam, it pushes private investors further up the risk ladder.

It’s not good for cash and bonds. More money and credit creation devalues it. This incentives more traders and investors to look for alternatives that will at least hold their value.

When it comes to tapering, financial assets perform weaker in the lead up to the process. Instead of liquidity being pushed out into the system, it’s being withdrawn. This is less favorable to risk assets.

When QE is being pulled back, this pushes money back down the risk curve.

The following chart shows a general sketch of how QE and QT impact capital flows.

(Source: Nordea)

Emerging markets

When tapering starts being discounted into markets and liquidity is expected to dwindle, the riskiest emerging markets are hit first.

So EM traders and investors need to be the most prepared. What developed market central banks do (with the Fed being the most important to watch) is very important to what happens in EM.

Fed tapering works to reduce the marginal availability of dollars. If this comes at the same time rate hikes are coming into the picture this can put dollar funding conditions to the test.

Countries that are particularly vulnerable include those with:

- large current account deficits

- high external debt service burdens (debt that’s not denominated in their own currency*), and

- low foreign exchange reserves

*When debt is denominated in foreign currency, higher interest rates in that currency drive up its demand (holding all else equal). An appreciating liability (i.e., the foreign currency) makes it more difficult to service, creating a squeeze.

Small caps underperforming large caps

Small cap stocks starting to underperform large caps is another “under the hood” indicator.

Small caps tend to benefit most from easy liquidity policies as they tend to be less diversified and overall riskier businesses.

Risk assets

Risk assets as a whole generally go from strong performance – depending on how strong the QE program was – to performing weaker.

Even when EM starts lagging and small caps start lagging large caps, this does not yet mean stocks as a whole are declining.

But it means you may be getting there.

Trading is a game of thinking ahead

Thinking about tapering and liquidity withdrawals is necessary when QE is still going on.

Trading will try to outsmart their peers by front-running developments.

For rates traders, rate curves (e.g., 5s30s) tend to steepen in the period between when:

a) QE is still ongoing but central bankers are contemplating tapering to when

b) tapering actually happens.

Then it tends to flatten again. Tapering tends to reduce inflation expectations and can lead to falling interest rates.

Safe assets like government bonds and even cash can start looking attractive in relative terms and as stores of value (capital preservation) as liquidity is being withdrawn and made more scarce.

Inflation can be a material determinant of when tapering occurs

Inflation is a big variable in central banks’ reaction function in terms of when to taper.

Higher inflation increases the odds of tapering – i.e., how soon and to what extent.

Actual inflation and market-based expectations of inflation may be different.

The bond market is often considered the best indicator of inflation. So-called bond vigilantes will sell bonds if inflation picks up and thwart any prospective tapering by pressuring yields higher.

Central banks may even redefine what they mean by inflation.

The Fed, for example, has released statements such as

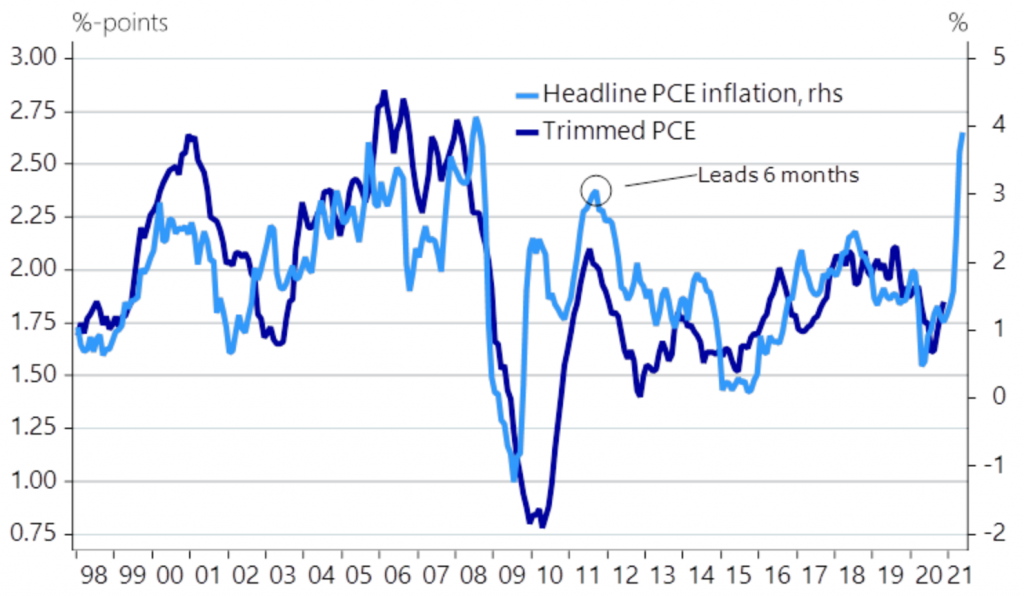

“Some participants commented that recent readings of inflation measures that exclude volatile components, such as trimmed mean measures, had been relatively stable at or just below 2 percent”.

An easy way to change the level of inflation is to exclude the components that have increased the most.

Core inflation generally excludes things like energy and food given their commodity inputs. (Commodities are volatile and therefore core is meant to better capture the trend of inflation rather than its level.)

Trimmed mean inflation is generally lower than the more commonly used measures, like CPI, PCE, and PCEPI. Trimmed measures tend to lag untrimmed measures.

Headline PCE inflation leads Trimmed PCE inflation

(Source: Nordea and Macrobond)

Tapering ends up being much talked about, but hard in practice

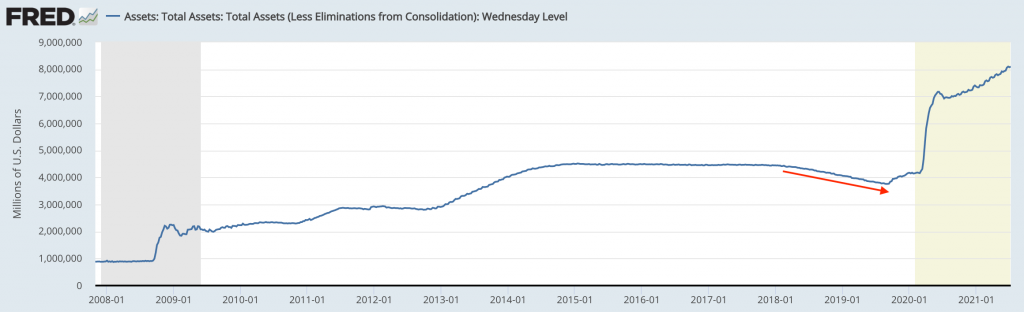

When the Fed began tapering as 2018 went along, it ended up only tapering from $4.5 trillion to around $3.8 trillion. The commitment to tapering and pulling back on liquidity in 2018 led almost all risk asset markets to perform weakly that calendar year.

It eventually gave up in September 2019 when there were issues in repo markets.

Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

Tapering is difficult, especially when deficits are high and interest rates are very low. This means the incentives to hold the debt are also correspondingly low, leaving more of the buying onus on central banks.

This means they often have to buy more bonds, not less.

In the end, it’s all about the supply and demand.

Conclusion

For developed markets, because their debt yields negatively in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, there’s a lack of incentives for domestic and foreign entities to hold it.

The Fed says they want to taper eventually, which is always the case whenever there’s a QE program ongoing.

But with the large deficits and lack of demand for the debt they’re pushing out, the QE is essentially permanent.

They can raise rates to make it more attractive, but that feeds into higher borrowing costs and a slowdown in the real economy. They’re essentially stuck.

Eventually, it’s going to hit the dollar (and other currencies undertaking similar policies) and you’ll see enough currency devaluation and changes in real interest rates to get to a new balance of payments equilibrium.

In other words, at some point – nobody knows when – that means you’re going to have forced selling of goods, services, and financial assets and reduced buying of them by American entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

In terms of what that means for portfolios and asset allocation at a broad level, diversifying currency exposure and being wary of US debt assets can be prudent. Portfolios should ideally be diversified broadly among different assets, different asset classes that can perform well in different economic environments, and different countries and currencies.

In terms of what tapering may mean for portfolios, traders should be most wary of riskier emerging markets, small cap exposure relative to large cap, and risk asset exposure as tapering expectations get more serious.