Characteristics of a Market Downturn

In Part I, we covered the circumstances governing a healthy bull market and the unhealthy bull market associated with a bubble. In Part II, we covered the characteristics of the top, which leads us into part III, or the downturn phase.

Recessions vs. Depressions

The market dynamic is normal recessions is different from the one in abnormal recessions (“depressions”).

Some think a depression is just a really bad recession, but they’re two distinct naturally occurring events.

The basic difference between the two is that in recessions monetary policy is still effective while in depressions it is not.

In regular recessions, the imbalance between the supply of money and the need for it to service debt can be remedied by cutting interest rates.

Depending on the extent of the imbalance the central bank can cut interest rates, that gets a floor under the financial markets, lending and borrowing is incentivized to the extent needed, and the business cycle starts over again.

When inflation starts to tick up, then the central bank raises interest rates, usually creating a downturn in the economy.

That’s the normal dynamic that most people are accustomed to. These business cycles usually go in 5- to 10-year increments.

Cutting interest rates has the following effect:

i) credit becoming cheaper stimulates the demand for it, and therefore stimulates economic activity (credit conveys buying power)

ii) boosts asset prices through the present value effect

iii) eases debt servicing burdens through more favorable refinancing rates, lower interest on adjustable rate loans, and so on

iv) more money is put into the economy, which provides the means to service debts

This doesn’t and can’t happen in depressions. Interest rates can’t be reduced too much below zero.

Once at zero nominal rates, lenders no longer receive returns in nominal terms and are unlikely to get any returns in real terms because policymakers don’t like tolerating deflation. (Nominal returns are real returns plus inflation.)

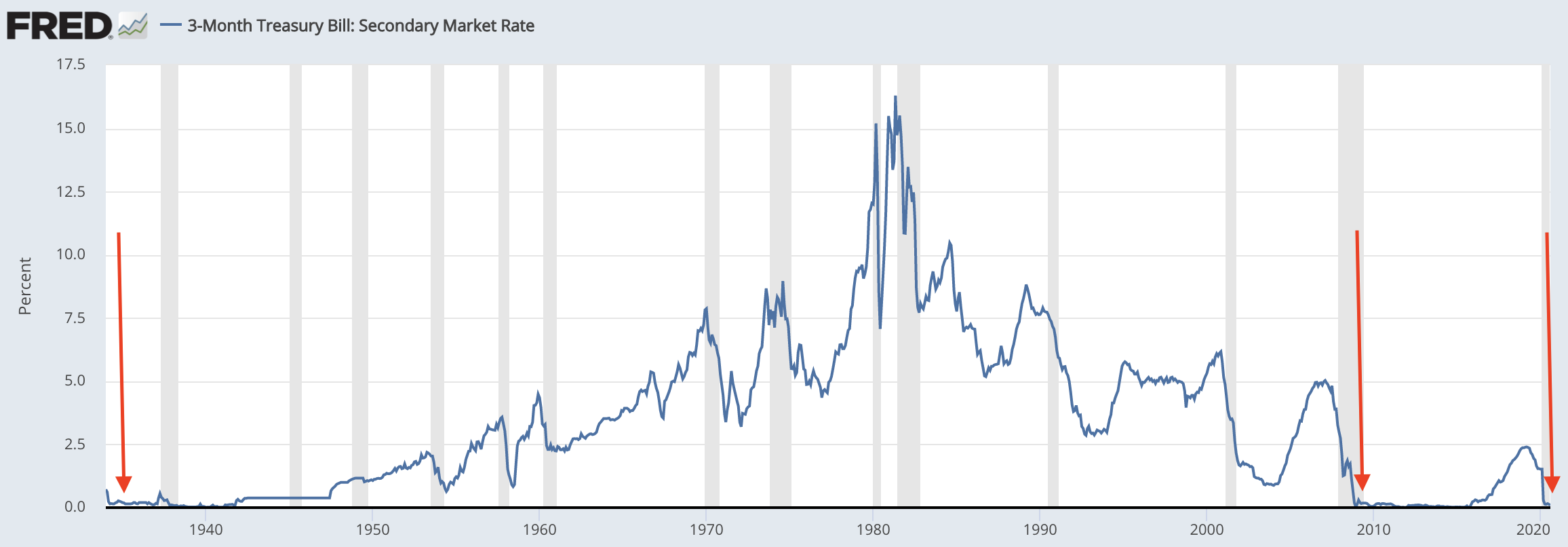

This is the problem in all the main reserve currency areas of the world (i.e., the US, developed Europe, Japan). It became the overriding problem in the 1930s, 2008, and 2020 crises in the US, as interest rates hit zero each time.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

In emerging markets, an additional risk is currency outflows and weakness.

Interest rates can’t be pushed down more without risking more capital flight and a potential balance of payments crisis, where the currency declines and the creditworthiness of the country falls.

This has been a chronic issue in markets like Turkey and Argentina, for example.

It is less prevalent in developed markets (what this current series of articles is focused on), but can happen if market participants lose faith in the currency and bonds and no longer want to hold these assets.

In normal recessions, the central bank cuts interest rates about five percent. So any time interest rates are near the zero lower bound, the risk of running out of traditional policy room is quite high.

Past depressions

In the US during the 1930 to 1932 period, there was a major bust after the debt-fueled prosperity of the 1920s came to a head.

The debt crisis that emerged in 1929 was different from the other “panics” that policymakers had encountered in their lifetimes (e.g., 1907, 1920). Accordingly, they didn’t recognize well what kind of crisis they were in and were late to react to it.

Interest rates went to zero, but that wasn’t enough so eventually they bought longer duration assets starting in July 1932. This also happens to be when stock prices bottomed.

In 1933, there was the dollar devaluation against gold and breaking the “gold clause” from debt contracts. This helped borrowers relative to lenders by making liabilities cheaper and easier to service.

In 1937, the Fed tried to tighten monetary very slightly. But debt was still too high relative to output and there were other factors – e.g., WPA employment program was reduced, veterans’ bonuses were fading, and currency devaluations in Europe caused the dollar to rise.

Stocks fell back by more than 50 percent. Moreover, when interest rates are very low, the duration of financial assets is longer. This makes them more sensitive to the movement in interest rates.

From 1938-40, there was monetary and fiscal easing – e.g., gold sterilization to prevent dollar appreciation, increase in government-sponsored employment, a $2 billion fiscal bill (2 percent of GDP at the time) – but didn’t result in much of a boost since interest rates were already very low.

The real pickup in economic activity started coming in 1940-41 from supplying the Allies and preparing for potential war entry. Then there was the official entry that kept war production flying.

The Federal Reserve monetized government spending from 1942-47 through a cap on long-term Treasury bonds at rates of 2.5 percent and short-term rates at 0.375 percent. The Fed stepped in to buy the bonds whenever rates approached those levels.

This is known as yield curve control, or YCC>

The same dynamic came into play in 2008-09 with the subprime housing bust.

The 2008 financial crisis was managed better than the 1930s crisis because of greater know-how on how to rectify the situation.

The Great Depression was naturally a common comparison because of the “out of room” interest rate dynamic.

Learning from the mistakes of the 1930s when the Fed was slower to ease and even had to tighten policy to defend the dollar’s peg to gold.

When the Fed lowered interest rates to zero in 2008, they realized that wasn’t enough and had to move onto a secondary form of monetary policy.

Like in the 1930s, the Fed purchased Treasury bonds to lower long-term yields.

The beginning of a depression

When a depression begins, restructurings and debt defaults hit various players in the economy. It is sharp and sudden, hitting the most leveraged lenders (often banks) the hardest.

The entities at greatest risk are institutions that are both highly leveraged and have the most concentrated exposure to distressed borrowers.

They are at risk of also creating issues for other creditworthy entities and bringing down overall economic activity.

These are usually the commercial banks. But as credit systems have become more complex over time this also includes other lending institutions as well.

Theses pop up because they are outside of the traditional regulations and/or they are subject to different regulatory standards.

These include non-bank lenders, hedge funds, proprietary trading shops, insurance companies, broker-dealers, and special purposes entities.

When the downturn hits, the fears of both borrowers and creditors tend to feed on themselves in a self-perpetuating way.

Lending decreases, which makes it more difficult for borrowers to make their debt payments. When it becomes clear that borrowers are not in good shape, lenders also pull back.

This contracts spending on goods and services and investment. Incomes and asset prices decline.

Also, when borrowers cannot meet their debt service requirements to their lenders, these lending institutions also cannot make due on their obligations to their creditors.

In other words, they don’t have the money to meet their obligations unless they are protected by the government.

The inability to cut rates

Cutting interest rates is no longer effective because the floors on risk-free borrowing/lending rates have been hit. As credit spreads rise, the borrowing rates on risky loans increase.

This makes it more difficult for those debts to be serviced.

Lowering interest rates also doesn’t help lending institutions that have liquidity problems. Many of them are suffering from “runs” where people want to get their money out.

At this stage, debt defaults and a pullback in spending and investment (i.e., austerity) win out.

Inflation expectations go down, which benefits safe government debt and cash.

They are not yet balanced by the stimulative effects of debt monetizations, which involves the printing of money to cover these debts. Money printing is inflationary.

While some might think that printing money is inflationary, it’s the total amount of spending in anything (i.e., financial assets, goods, services) that moves prices.

In a depression, credit is contracting faster than it’s being filled in. The extra money created and put into the economy by the central bank is needed to fill in that hole.

If money creation is positive but it doesn’t compensate for the contraction in credit, then prices will still fall even despite the inflationary influence of the money printing.

When investors and other entities are no longer willing to lend and borrowers are having issues finding cash to cover their debt payments, liquidity becomes a major concern. (Liquidity is the ability to turn investments into cash.)

There are a lot of assets for sale and not enough buyers.

Example

For example, if you have a $100k investment, you normally believe you’ll be able to sell it for $100k in cash.

In turn, that $100k can buy you an equivalent amount of goods and services.

But in times of stress, when that money is usually most needed, it’s the hardest to come by.

The amount of financial assets is always large relative to the amount of money in circulation.

This is because it’s much easier to create claims on wealth than it is to produce goods and services that provide value to the extent people are willing to pay for them.

So, trying to convert a lot of financial assets into money all at once creates sharp, sudden moves down in markets.

In order to relieve this stress and enable the conversion of financial assets into money and help people buy goods and services in bad times, the central bank has to fill the gap by creating the money (inflationary, holding all else equal). Or else it has to allow more defaults (deflationary).

The depression can be both a cause and effect of cash flow and solvency problems. Each have different characteristics.

Cash flow issue

A cash flow issue occurs when an entity doesn’t have enough cash to meet its obligations. This is often because its lenders are taking money away their support. In other words, there’s a “run”.

A cash flow problem can come about even when the entity has sufficient capital because this capitalization is in the form of illiquid assets that can’t be readily converted into cash to meet its needs.

The lack of cash flow is an acute and immediate problem and usually the main trigger and issue associated with most debt crises.

Solvency issue

A solvency issue means that an entity doesn’t have enough capital (in the form of equity, or ownership of assets) to operate any longer. In other words, it’s broke and needs to be shut down.

The nature of solvency issues can be impacted by regulatory and accounting rules. So, the severity of debt problems can occur in some part due to existing laws in the jurisdiction(s) in which it operates.

Working out each problem

Both problems require a different approach to help rectify.

A cash flow issue is usually easier to solve than a solvency problem. This involves monetary or fiscal policymakers providing the cash to troubled entities they want to save and providing guarantees that resolves it.

A solvency issue (i.e., the entity doesn’t have enough equity capital) needs to be rectified by receiving additional equity capital and/or change the regulatory and/or accounting rules to effectively conceal the problem.

This can be done through fiscal policy (e.g., government taking a stake in the company) or through monetary policies if the debt is denominated in the currency the central bank is responsible for.

An example of how regulatory and accounting rules matter for solvency issues

The banking crisis of the 1980s was different from the banking crisis of 2008.

In the 1980s, the accounting landscape didn’t feature the mark-to-market properties it would 20+ years later.

This is because back in the 1980s not as many loans were traded daily in the public markets.

With having to mark losses to market continually, banks were not as “insolvent” as they were in 2008 when mark-to-market accounting became common practice.

Because of this difference, banks in 2008 required capital infusions to improve their solvency by fortifying their balance sheets.

Accounting differences led to different management of their issues, and in the end both cases were successfully managed.

The role of existing regulation in arresting economic declines

Going into the downturn, some of the protections and regulations associated with past declines are usually in place. They often work to some extent. These can include financial supports and guarantees to inject capital into systemically important companies and institutions and/or nationalizing them to ensure they remain healthy.

But they usually aren’t adequate because the nature of the debt crisis is different from those in the past.

The next type of crisis typically impacts different types of businesses than the most recent ones.

Regulators largely work by looking in the rear-view mirror rather than anticipating problems that a trader or investor might have to do in order to play the markets well.

A lot of lending goes into the shadow banking system, or the non-bank lenders discussed above.

These are new entities who often offer products and instruments whose risks are not well understood and have inadequate regulations.

Often this means unique ways of investing and lending in asset classes that cater to less sophisticated investors. Or instances where there is an asymmetry in information between the party selling the asset and the entity buying.

What happens to these issues largely depends on how policymakers react to them and how free they are to do what’s in the best interests of the whole.

Downturns are not psychological

It is not a matter of just getting investors to be “less scared” and persuading them to get into riskier investments (e.g., stocks, high-yield credit) back from safer ones (cash and government bonds).

The dynamic is not psychological or an emotional reaction to “turmoil”.

It is driven by the supply and demand of – and the relationships between – money, credit, and goods and services.

Psychology can play a role, particularly as various players see their liquidity positions turn down.

However, even if everyone’s memories were wiped clean of the event(s) that caused the crisis, everyone would still find themselves in the same set of circumstances.

Debtors’ obligations to deliver money to their creditors would be too large relative to the amount of money they are bringing in through revenue, new capital infusions, and cost cutting.

The government would face the same set of choices and same set of trade-offs, which would have the same set of consequences, and so forth.

The value of money

On top of this, if the central bank creates money to fill in the gap, the value of money becomes more of a concern. Creditors worry that what they’re being paid back in will be less than what they lent out.

What most think of money (i.e., what payments are settled with) is actually credit (i.e., a promise to pay).

Credit can be made out of thin air and disappear when things are bad.

When you buy something in a store on credit you are offering a promise to pay in the future. The owner of the store has a credit asset and you have a credit liability.

The money to pay for whatever you bought didn’t come from anywhere. It was simply credit created on the spot.

It also disappears in the same fashion. This is done by either covering the debt (by paying money) or if it’s never paid (effectively defaulted on).

If the buyers of the goods and services from the store won’t pay the credit card company the credit card company won’t pay the store owner, then that credit asset isn’t actually an “asset” at all.

It simply doesn’t exist and is only covered when paid with money or another form of credit (which opens up another liability for whoever paid it).

A big part of an economic decline is learning that some assets don’t actually exist and/or don’t have the values believed

In a market decline, many discover that what they thought was their wealth is just a collection of what are essentially promises to pay them money that can’t be fulfilled.

For an asset to have value, somebody needs to create the economic earnings (in the form of future dividends and distributions) to give it a value in line with its market price. Until then, it’s simply a promise to pay.

If those promises aren’t kept, then the wealth no longer exists.

Whenever investors try to liquidate assets they are essentially testing their ability to get paid.

When they can’t, this induces “runs” and further sell-offs in the securities until they meet another buying price at a lower equilibrium.

Those who experience runs have problems raising money and capital to meet their needs, so default tend to self-propagate. This is true of most entities that capitalize themselves heavily with short-term funding.

Defaults and restructurings take off, especially on the most leveraged lenders. This causes a loss in confidence for creditors (in their ability to be paid back) and borrowers (in their ability to continue to borrow or roll over their debt).

This creates a dash for cash and a shortage of it. In other words, it’s a liquidity crisis.

Dynamics of a liquidity crisis

In the early goings of a liquidity crisis, the money coming in to debtors through their incomes and borrowing is not enough to meet their obligations.

Assets have to be sold and expenditures need to be cut in order to raise cash.

This process causes asset price to drop. This reduces the value of collateral and new borrowing. Borrowing leads to spending, and spending is somebody else’s income.

So, the issue from asset prices dropping is not only about wealth (i.e., financial assets being promises to pay) but the feed-through into incomes.

Borrowers’ creditworthiness is measured as a function of:

i) the value of their assets and collateral in relation to their debts (net worth and favorable credit ratios), and

ii) the size of their incomes relative to the size of their debt service payments

When their net worth and incomes fall faster than their debts, borrowers become less creditworthy. As a result, lenders are less inclined to lend, which goes on in a self-reinforcing way.

This initial phase is dominated by the debt reduction dynamics (defaults and restructurings) and spending cuts (austerity). Little is initially done to relieve these debt burdens by creating money.

A piece of debt to one person is an asset to another person. So, when the value of these assets is heavily cut, this reduces the demand for other investment assets, as well as goods and services.

Write-downs as part of the debt reduction process can be effective when it’s done sufficiently such that the debtor is allowed to service the restructured loan.

If a loan needs to be written down by 50 percent in order for the debtor to be able to pay on it again, the creditor sees a 50 percent reduction in its assets.

That seems like a big hit on its own, but the effect is much more in reality. Most lenders are leveraged, meaning they borrow in order to buy assets.

For a creditor that is leveraged just 2-to-1 (i.e., the value of their assets is twice their net worth), it would see its returns effectively wiped out.

For example, let’s say a lender has $1,000 in assets and debts of $500. In that case, net worth is $500.

If the value of the assets falls by just 20 percent, then the value of the assets is now $800 and the debt amount remains at the same $500.

Net worth has gone from $500 to $300, which is 40 percent less even though assets fell just 20 percent. That means the impact of 2-to-1 leverage has double the influence on net worth. 3-to-1 leverage has triple the influence, and so forth.

Banks are traditionally leveraged at 10-to-1 or more. So even a five percent reduction in wealth is painful for them and the economy. Double-digit losses on their assets themselves can wipe them out completely and cause systemic, economy-wide issues.

Even when debts are being written down, debt burdens rise as spending and incomes decline. Debt levels also rise relative to net worths.

When debt-to-income and debt-to-net worth ratios increase and creditworthiness declines, credit availability drops, so the contraction in credit becomes self-reinforcing on the way down.

Investors and higher net worth individuals experience a large loss of wealth during the depression phase because financial assets drop so severely.

Declines in equity prices generally fall around 50 percent, though can be much worse.

For example, Iceland’s stock market fell more than 95 percent in the 2007-09 crash and the US stock market fell 89 percent peak to trough from October 1929 to July 1932.

The rich see their wealth drop as do their incomes. They often face higher tax rates because governments need more money facing shortfalls, and the political class is often hostile to them.

As a result, they want to move their money and assets out of the country, which contributes to currency weakness (and exacerbates the problem even more).

They also want to avoid the higher tax rates, which creates arbitrage effects by moving themselves and/or their assets to other jurisdictions.

Sometimes they see wealth taxes put into place, but does a poor job of collecting revenue become most of what’s called wealth is illiquid.

They seek safety in more liquid investments that are not credit dependent. This means shorter duration and/or lower risk government bonds, gold and precious metals, or cash.

The real economy and financial economy suffer.

When monetary policy is constrained as it is during a depression, the contraction in credit produces severe economic and social problems.

Workers see their incomes decline. Job losses are high.

Those who were able to make a living and provide for themselves and their families lose the opportunity to work, which creates destitution or dependency on assistance from the government and/or others.

Homes often go into foreclosure because owners are no longer able to pay their mortgages. Different types of savings which had been pushed into riskier assets to get higher returns – e.g., retirement accounts, college/university savings, personal accounts – are badly damaged or wiped out.

If policymakers don’t act with sufficient monetary stimulation, this set of conditions can become chronic for years. Generally, central bankers will do whatever they can to “save the system”.

How to manage depressions

There are four main categorical ways depressions are managed:

i) debt defaults and restructurings

ii) spending cuts (austerity)

iii) money creation and debt monetization

iv) transfers of wealth from those who have an “excess” of it to those who don’t (i.e., tax and redistribution)

Policymakers have these main levers to pull, but it’s important to note that they each have different impacts on the economy and creditworthiness of the entities within it.

The basic idea is to get the mix right by getting the deflationary (depressive) and inflationary (stimulative) influences to largely offset.

When done well, this gets the economy growing again without deflationary or inflationary pressures that are too onerous either way.

Policymakers generally have issues getting the balance right between the four initially.

The issue becomes highly political and creates social tensions as taxpayers are irate at the debtors and financial institutions that helped bring about the debt crisis.

Accordingly, they don’t want the government – which is essentially their tax money – to bail them out.

Policymakers also don’t want to incentivize this behavior in the future so they generally want borrowers and creditors to suffer the consequences of their decisions. Otherwise, “moral hazard” can become a major concern.

Accordingly, at first, policymakers usually don’t want to provide government supports.

But at the same time, not providing support causes the debt contraction and painful economic malaise to get worse. The longer the depression phase goes on the costs to not providing support increase in excess of the costs to doing so.

Eventually they choose to create money, monetize debt, and provide lender-of-last-resort related backstops to get the economy going again into a positive growth trend.

If they do these things well, the depression is more likely to be short-lived.

For example, the depression of the early 1930s was long and severe due to the holdout of necessary supports. The 2008 decline was shorter and the contraction less severe.

The 2020 decline was sharper at first, but took less time to correct as the central bank had been in that position before and were as aggressive as they needed to be to get the bottom (printing at about 100 percent of GDP to get the bottom a little after a month past the top in the stock market).

Failure to act quickly and sufficiently means a prolonged depression is likely, such as the Great Depression in most of the developed world in the 1930s and Japan in the 1990s following the popping of its bubble in the late 1980s.

The two biggest impediments to managing a downturn and debt crisis

The two biggest challenges to managing a debt crisis well are:

i) The inability to know how to make the right decisions to handle it well, and

ii) The inability for policymakers to take the necessary actions due to political constraints or statutory limitations

Or in simple terms, ignorance and lack of authority are the main reasons. These constraints can be even bigger issues than the debt problems themselves, which can be resolved if the right actions are taken.

Being a successful economic policymaker is even harder than being a successful investment manager or trader. Not only do you need to know how to anticipate what comes next as either a trader or policymaker, but policymakers also need to be able to make things turn out well.

They have to know what should be done all while managing the political aspects of their job. That means navigating those hurdles and having the savvy to deal with various self-interested parties who may not have the interests of the whole at stake.

Conclusion

In this article, we covered the characteristics of the downturn phase. We covered why and how debt crises happen, the natures of them (e.g., cash flow issue, solvency issue), and how they’re resolved.

In the next part of this series, we’ll look further into the four main ways debt crises are rectified and how each are normally used (debt defaults and restructurings, austerity, money creation and debt monetization, and wealth transfers).

These are used to get a bottom in the financial markets first, then a bottom in the economy. (Markets lead the economy.)