Is Bitcoin A Viable Alternative to Stocks and Gold?

Cryptocurrency is an incredible invention. It’s increasingly become a type of currency and store of value that’s been programmed into a computer and sustained to last.

At this time of increased money and debt creation as economies try to relieve their economic problems – a process that will go on for some time – there is an increased need for alternative assets with limited supply.

This can include things like gold, other precious metals like silver or platinum, certain kinds of stocks with steady or growing earnings, and other types of commodities.

But many of these markets aren’t as deep as they would ideally be.

Many consumer staples stocks – some viewed as a fixed income alternative – have been bid up to very high levels, some north of 35x earnings estimated one year out.

The inverse of that earnings multiple is the yield. Receiving less than three percent yield for a stock, with all its volatility and price movement, is risky.

Many also want assets that can act as stores of value and be held privately. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies can possibly fill this role to some extent.

At the least, we can say that bitcoin has done well in terms of going from an idea that was more speculative and one that could fizzle out to one that’s probably here to stay.

Is bitcoin both the present and future of cryptocurrency?

Bitcoin may eventually get replaced as the top cryptocurrency at some point in the future. Bitcoin is around 80 percent of the total crypto market.

This market share is not far off from where it was before its popular 2017 run. Other cryptocurrencies, including ICOs (tokens sold by companies promising new business models), gained in 2017.

But bitcoin has since regained much of that share and re-established itself as head and shoulders above everything else.

Stablecoins are excluded from this share because they’re supposed to be backed by fiat currencies, mostly the US dollar. Tether (USDT) is the most popular stablecoin and is currently under investigation by multiple government agencies as to whether it was backed by the dollars its operators said it was.

Share of cryptocurrency market (BTC, ETH, others ex-stablcoins)

Will bitcoin lose share and eventually be replaced by something else? Traditionally this is the way things have worked, no matter if it comes to the world’s leading empires or companies.

If you look at the top companies over time, they tend to fluctuate a lot over 20-30 years.

Most of the top companies today – e.g., Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon – either didn’t exist 20-30 years ago (the first three in that group) or were very small and essentially reinvented themselves (i.e., Apple with the iPhone in 2007 and Microsoft’s recent and growing cloud focus).

Before that, in the early 1990s, we had companies like ExxonMobil, Wal-Mart, and General Electric.

Go another 20-30 years before that, you had companies such as IBM, AT&T, Sears, and Eastman Kodak.

Companies fail to evolve and entirely new types of companies come up to replace them.

Cryptocurrencies could be similar based on what the market wants, in terms of supply, governance, liquidity, technological robustness, privacy, and so on.

It comes down to what will it be used for and what amount of demand will bitcoin (and its competitors) have.

Bitcoin’s supply and demand

The supply of bitcoin is known, so it’s price is a function of its demand.

That said, while bitcoin is supply constrained, digital currencies as a whole are not. There are various others and they will continue to compete with incumbents.

Naturally, something that’s very profitable tends to not stay that way forever because it attracts competition.

So, that competition will play a role in the prices of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

Bitcoin is designed to work in the way that it does in perpetuity, so it’s ability to evolve is constrained accordingly.

Being supply-constrained helps, but it’s not enough in itself if the market demand isn’t there.

For example, even if fax machines were in limited supply, they still wouldn’t be worth much because new inventions have come along to mostly take their place as a way of sending documents and information.

Bitcoin cybersecurity

Bitcoin has worked well for over a decade and has not had any major hacks. Nonetheless, this is a risk that can’t be ignored. Naturally, hackers understand points of vulnerability and tend to be ahead of cybersecurity systems in many ways.

It’s a risk to all financial assets in general and not only digital assets alone. And it’s part of what makes assets that can be privately held valuable, such as gold and other tangible items.

Bitcoin can be held offline through “cold storage” (a type of off-the-grid digital wallet), but it’s difficult to do and few do it.

So the question is whether bitcoin is sufficiently protected against these cybersecurity risks?

It’s a risk that can be extended to all financial assets that mostly exist in the form of digits.

Bitcoin regulatory risk

Throughout time, governments have tried to regulate or ban alternative assets that were beyond their control.

This has included gold. For example, gold was banned in the United States from 1933-1975, with some restrictions being loosened in 1964.

Only certain gold items were permitted for private ownership, such as collector coins, jewelry, and gold used for industrial purposes.

Bitcoin is probably not going to be as private as some people believe. Bitcoin is built off blockchain, which is a private ledger. A lot of it is held in a non-private way.

As a result, privacy is not likely to be protected if governments or cybercriminals want to know who has what.

If the government wanted to crack down on it, most of those using it wouldn’t be able to do much about it, and its price would fall in a big way.

Bitcoin could essentially become a victim of its own success.

The bigger it gets, the more likely it’ll be that governments will want to prevent the use of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as a way to skirt around the payment systems governments have set up.

This is why central banks were set up, first in the 1600s, and central monetary authorities have been around for even longer than that.

Governments want to control the money and credit within their own territory.

So, if an alternative currency starts becoming more successful and attractive to transact in and hold as a store of wealth, like gold or bitcoin, policymakers will want to cut down on that.

Their ability to squelch these alternatives is pretty effective if they choose to do so.

What central bankers have to say

It’s already on the US’s radar, per the comments of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen:

“Cryptocurrencies are a particular concern. I think many are used, at least in a transaction sense, mainly for illicit financing. And I think we really need to examine ways in which we can curtail their use and make sure that money laundering doesn’t occur through those channels.”

The ECB’s Christine Lagarde echoed the same thoughts:

“[Bitcoin] is a highly speculative asset, which has conducted some funny business and some interesting and totally reprehensible money laundering activity. There has to be regulation. This has to be applied and agreed upon … at a global level because if there is an escape, that escape will be used.”

Bitcoin’s sources of demand

As mentioned, bitcoin is an interesting store of wealth-like alternative, with its limited supply and you can move it places. But if you look at the sources of demand, central banks aren’t going to buy it as a reserve asset.

At the same time, institutional investors don’t value it much as a currency hedge when real interest rates become excessively low.

It’s still a speculative asset where the buyers and sellers are mostly using it for purposes of reselling.

As a primarily speculative instrument, it’s one of the first types of things that people are going to want to sell to raise cash in bad financial times.

So, its diversification value is limited.

In other words, if you want to figure out how much you would want to own percentage-wise to be balanced among various assets, it’s not going to be that much, if anything.

Any material bet is going to be a speculative wager where you have to be okay with the prospect of potentially losing 80 percent or more of your investment allocated to it.

Right now, there’s a lot of money and debt creation going on and all that liquidity has to go somewhere, so it’s propping up a lot of risky stuff.

A currency has three main characteristics:

a) a medium of exchange

b) a store of value

c) the government wants to control it

It’s not really a medium of exchange because you can’t buy much with it. There are certain mainstream products and services that can be purchased with bitcoin, but it’s not a lot.

It’s not really a store of value because it’s too volatile because of the speculative nature of it.

And it’s an off-the-grid payments system, so it’s not something the government wants to be around in any material quantity.

If bitcoin becomes large enough, various governments are probably going to use whatever regulatory teeth they have to try to prevent ownership of it, and that will hurt its demand.

Is bitcoin really about the dollar (and other devaluing reserve currencies)?

People want to protect their purchasing power over time and don’t have a lot of alternatives relative to the potential need for them.

For example, even with global debt levels at over $300 trillion, the global gold market, including all miscellaneous forms, is only about $13 trillion.

More understand that the dollar has to undergo a sizable devaluation over time.

The US is really pushing the limits of the following mix:

a) the dollar being weaponized (through sanctions) to help the US get what it wants internationally

b) producing a very large amount of dollar-denominated money and debt

c) fueling its debt binge through negative (and declining) real returns on the debt (about a minus-1 percent 10-year real yield), and

d) having a fiat-based monetary system where the value of the money is based on government authority alone

The pricing dynamics of assets

With something like gold, when it goes up, it’s not that the utility of it is getting better.

Gold is a long-duration, non-credit dependent, store of wealth asset that more closely approximates a currency instead of a traditional growth-sensitive commodity.

Gold is simply priced as a certain amount of currency per ounce.

When it goes up, it’s not that gold intrinsically has more value, it’s that the value of money is going down in gold terms, and accordingly the value of gold is going up in money terms.

Gold has less to do with the metal and more to do with the currency it’s being measured in, with its long-run valuation proportional to currency and reserves in circulation relative to the global gold supply.

That’s why gold can look like a good or great recent investment from the vantage point of being priced in some currencies but look like a recently mediocre or poor investment from its pricing in other currencies.

It’s a barometer for the value of money.

Bitcoin can be a similar type of asset. But the dynamic is clearly very different in terms of who the buyers and sellers in each market are.

But the dollar – or any national currency – does matter for both, as it serves as the reference point for valuation.

Currency is something that’s normally taken for granted.

When we hear something is $50 per share, we tend to only think of the stock. We don’t think of the inherent currency aspect, even though returns are a function of both the equity returns and the currency.

If it’s your home currency, it’s the loss of purchasing power that you have to be concerned about. If it’s a foreign currency, then you have the direct foreign exchange rate impact.

When the dollar does devalue, it’ll involve:

a) People wanting to sell USD-denominated debt and move their wealth elsewhere. This could mean into other countries and currencies or into alternative stores of value.

b) People wanting to borrow in dollars to take advantage of the cheap funding to make higher returns with it. After all, if a liability is falling in value, that’s a direct benefit to you if you owe it.

The Federal Reserve will have a bad trade-off to make. It’ll either need to:

a) allow interest rates to rise to unacceptably high levels to defend the currency (i.e., compensate investors enough for holding it), which will damage credit creation and economic activity, or

b) print money to buy Treasury debt, which further reduces the value of the dollar and debt denominated in the currency.

This will be worse if there’s a pop in inflation and rates begin to rise at the same time there’s reduced demand for the debt.

The expense associated with the Fed buying its own debt will increase. That increases the need to print money and the effective cost in terms of the devaluation.

Because when faced with this difficult choice of letting interest rates rise (and kill credit creation and economic activity) or devaluing money, central banks almost always choose to print money, buy their own debt (because there’s not sufficient demand elsewhere for it), and devalue the currency.

The devaluation of money is also the most low-profile way of getting yourself out of debt problems and therefore the most politically acceptable.

This process normally goes on in a self-perpetuating way because the interest rates being received on the money and debt are not adequate to incentivize investors to compensate them for the depreciating value of the currency.

It goes on until the currency and real interest rates are able to establish a new balance of payments equilibrium.

This essentially means there has to be a big payback of all the previous excesses in spending and borrowing of the past.

This entails enough forced selling of financial assets, goods, and services and enough reduced buying of them by US entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

It’s like budget controls and this economic reduction naturally comes with big social and political consequences, which can in turn hurt a country’s productivity and create and/or amplify big conflicts on how to divide up the shrinking resources.

Right now, all the money and debt creation seems good because it makes financial assets go up. It gets mistaken for a prosperous boom.

But it’s similar to gold’s pricing dynamics mentioned above. When the value of a currency decreases, it makes it price go up by default. Equities are the same.

In the short-run, it feels good and tends to feed on itself.

But as financial assets go up, that reduces their forward yields.

If you own a stock or a financial asset, you have a claim on somebody else’s future income. If the level of earning being discounted doesn’t transpire relative to expectations, that’s a big eventual risk.

And because the currency is being devalued – an FX effect for foreigners and lower real yields for domestic buyers – that money eventually leaves the country.

Increasingly, in today’s world, that means it’s going from the Western part of the world (e.g., US, developed Europe, Japan) to the Eastern world (e.g., China and other parts of south Asia).

So, to make a long story short, Americans would probably want to be insured against a long-run devaluation of the dollar in some capacity.

What to own in a devaluation-heavy world

Owning gold, silver, other precious metals, certain types of stocks that can quality stores of value (non-cyclical), other currencies, foreign assets, certain commodities, real estate, and so on that are quality stores of wealth that’ll hold their value well could make sense.

As for cryptocurrency, it’s a possibility.

Right now, it’s volatile because it’s highly speculative. There are government intervention risks and security risks. It has little correlation with the prices of the things that people need to buy, so it’s not necessarily a good way to protect buying power.

Their recent surge in popularity over the past several years – outside being an avenue for speculative activity – is a natural evolution of the fact that our current payments systems are slow and cross-border transactions are inefficient. Wire transfers through banks can take days.

If you transact through bitcoin or something like that (i.e., a decentralized network), it can get there more or less instantly. Our payments infrastructure isn’t modernized.

But it’s hard to see many central banks, large institutional investors, or very many multinational corporations and businesses transacting in it.

Some businesses have integrated into their operations or even balance sheet, and are essentially making a bet on it. Some will do it to compensate for a fundamentally weak underlying core business, but will spin it as something else.

Bitcoin’s valuation

Bitcoin’s valuation has a wide range of potential outcomes. It varies wildly by the day.

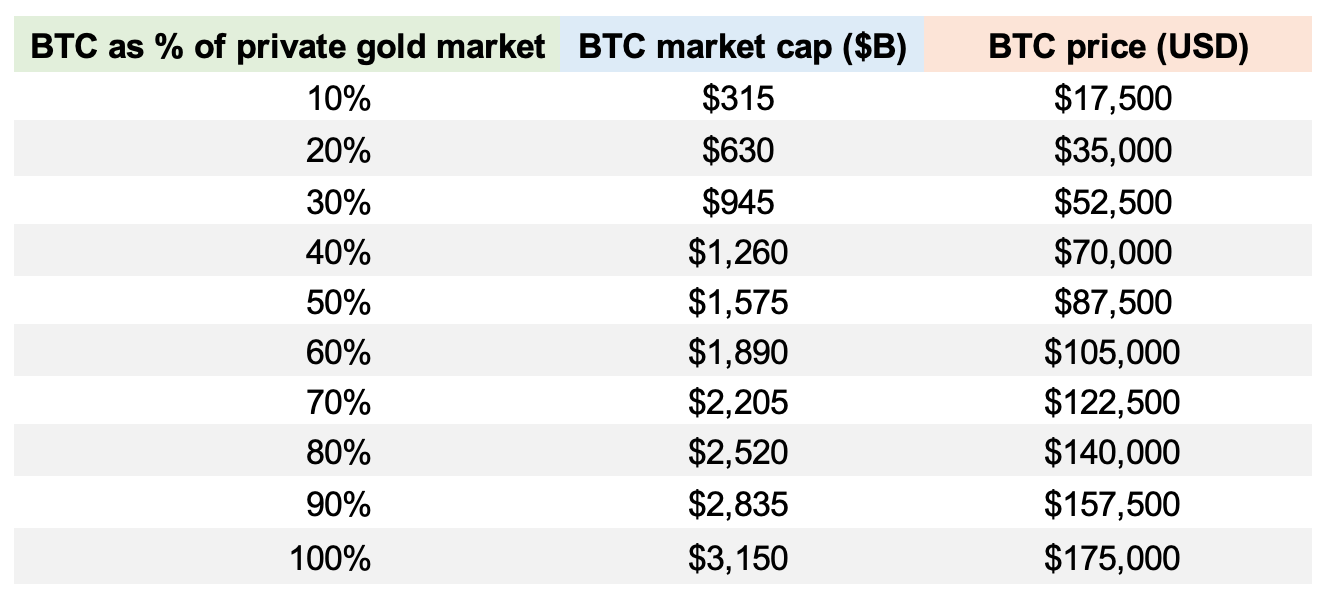

For example, what if you took global gold reserves and the people holding them wanted to diversify 20, 30, 40, or 50 percent into bitcoin?

Then what if those invested in bitcoin wanted to be less concentrated in it and wanted to move more into stocks and other assets (which would decrease the price of bitcoin)?

What if various governments began banning bitcoin? Or if public sector regulation became more strict but without draconian measures that would avoid threatening its existence?

Would more regulatory oversight help institutional adoption? Would more public oversight also trigger selling by those who value its “off the grid” nature?

There are various plausible, different possibilities you can come up with.

It means you have a very wide distribution of potential outcomes. There’s a very wide left- and right-tail.

Increased flows from bonds?

The biggest standard asset class globally is bonds.

Yet bond yields are so low in much of the world, their diversification properties have narrowed, and sovereign currencies are at risk of depreciation that there will be a search for alternative assets.

Bitcoin is currently 4-5 percent of the size of the global gold market, including jewelry and miscellaneous forms of gold.

We know that it has a much wider range of potential valuations relative to something like real estate, gold, or other traditional safe-haven sovereign currencies (e.g., dollar, yen, franc).

It’s also worth noting that bitcoin is not a very large market. Its market cap is only on par with a large-cap tech company.

This means liquidity is a limitation for institutional investors.

Gold -> Bitcoin

This hypothetical assumes that bitcoin becomes more gold-like in the way it’s perceived as a store of value.

If more people, institutions, and other entities wanted to convert more of their gold into bitcoin, or bitcoin became a certain fraction of the gold market, how might that estimate bitcoin’s price?

Bitcoin’s market cap is already around 20 percent of gold’s privately held market cap. This comes to a market cap of around $630 billion for bitcoin or about $35,000 per BTC.

This is right around where bitcoin’s price stood at around the start of 2021.

A rise to 30 percent would put bitcoin just north of $52,500 per BTC.

If 40 percent of gold was hypothetically converted into bitcoin, then that’s about $70,000 per BTC.

If 50 percent, then around $87,500 per BTC.

If bitcoin became as big as the market of the private holdings of gold, that’s about $175,000 per BTC.

Bitcoin price, if approximating certain valuation levels of the private gold market

If there are liquidity constraints or momentum-chasing behavior this could drive the price higher.

Moreover, at what point would central banks consider moving some of their reserves into bitcoin and how might regulators respond at various price levels?

Bitcoin’s market cap would approximate $1 trillion at around $72,000 per BTC. That’s close to five percent of US GDP and over one percent of global GDP.

Bitcoin as a reserve currency?

Within a country, the central government can declare that only the money that it creates is legal tender.

However, between countries the only money that’s acceptable is the currency that those who are transacting in agree to is acceptable.

This is why gold and reserve currencies have been so important in transactions between countries over time and why every great world power wants – and eventually has – a reserve currency.

The top three global reserves currently are the US dollar, euro, and gold.

People within countries typically exchange paper currency with others to do transactions in the country, but generally don’t recognize that the money is not valued much outside the country.

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies may have an advantage from the perspective of speed and low fees. But they have a long way to go.

The volatility also makes them difficult for merchants to transact in.

By the time they translate a bitcoin transaction (i.e., one that has settled) back into their own currency, a material fraction of its value could have eroded. There’s a speculation element outside of the business that most don’t want to risk.

The same goes for buyers. By the time they want to make a purchase, the price volatility may cause them to be short on funds. That is, even if they had already committed a sufficient amount when initially buying the cryptocurrency to complete the transaction.

For that reason, it’s easier and safer to simply do a transaction in national currency. Many illicit transactions are done in cryptocurrency because the price risk is naturally lower than the risk of getting caught for the type of transaction they’re trying to do (as Yellen and Lagarde alluded to earlier in this article).

Can central banks impose their own digital currency?

This is a question that many economists have asked as a way to meet market demand for digital currencies while at the same time fighting back against the spread of cryptocurrencies.

Naturally, one way to curb the use of cryptocurrencies in a “free market” way – i.e., outside of regulatory action – is to give them competition.

Almost 80 percent of the world’s central banks are either not allowed to issue a digital currency under their existing laws or the legal framework isn’t clear if they can.

For a currency to be successful and work like regular money it needs to be pervasively held, including internationally as a reserve asset, if feasible. Doing that in the digital realm is more difficult to do.

Governments cannot mandate that their citizens have this kind of money. As a result, granting legal tender status to a digitized central bank instrument could be challenging. Without the legal tender designation, achieving full currency status could be equally difficult.

Conclusion

Bitcoin is the top incumbent cryptocurrency by a wide margin.

However, it is very easy to copy, which represents one of its central risks, and there are concerns over its ultimate security/privacy, utility, speculative market dynamics, and future regulatory environment. Will governments do things to penetrate the secrecy of these transactions and even further restrict its already limited utility as a transactional medium?

So, a bitcoin investor may have to rely on the assumption that its first-mover status and established incumbency is enough of an advantage to anchor it over the long-run, or be able to anticipate inflection points in its dominance over time.

And that’s a question that’s fundamentally independent of cryptocurrencies’ ultimate utility as an asset class.

A lot of bitcoin payments are done for illicit purposes and if it becomes successful enough, then the government will want to crackdown on it. Janet Yellen mentioned its widespread use in conducting black market activity a few days ago, so it’s on their radar.

Bitcoin is an interesting store of wealth-like alternative, with some gold-like properties, with its limited supply and you can move it places.

If you look at the sources of demand, central banks are a long way from buying it. One could say that gives it more potential, but governments don’t want off-the-grid payments systems to exist in general.

Institutional investors also don’t value it much as a currency hedge when real interest rates become excessively low. It did poorly in the previous downturn, so its diversification value may be limited. Its turn-up has largely been a function of everything else going up in conjunction.

Still, if there is an outflow out of low-yielding bonds and diversification away from other traditional store of value assets, this could lead bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies to become more of an increasingly mainstream asset class.