Who Controls Bitcoin?

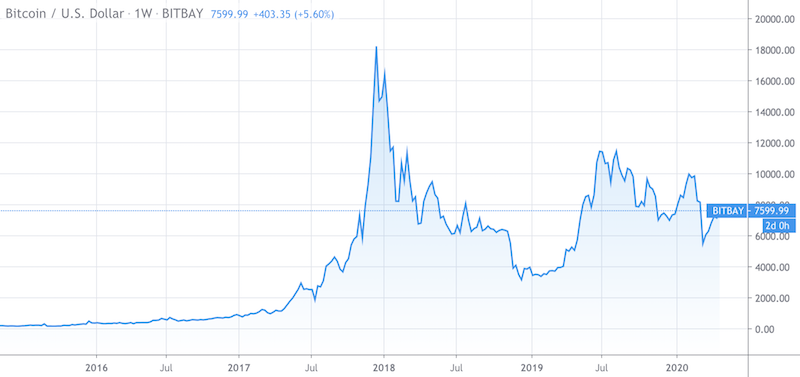

Bitcoin first came to prominence in the mainstream in 2017 during its speculative bubble. It rose to around $20,000 before retracing more than 80 percent. Since the top it’s mostly held under 50 percent of its former high.

(Source: Trading View)

Digital currencies are still largely misunderstood because of their decentralized nature, technological complexity, and the fact that they’re still relatively new.

For a digital currency investor, it’s also important to understand how they create value. Without value add, it’s basically a game of speculation.

Who controls bitcoin?

Bitcoin is decentralized. That means nobody technically owns or controls bitcoin just like nobody owns the internet, email, and text/SMS messaging. It is effectively a transmission system and an alternative payments system.

Bitcoin code is open-source and creating new bitcoins involves “mining blocks”. The total number of bitcoins in circulation can’t exceed 21 million. They’re about 90 percent there as of April 2020.

When will all the bitcoin be mined?

The production rates halves every 210,000 blocks. Based on that rate, it will take until around the year 2140 until all bitcoins have been mined. That means as time goes on, bitcoin will be mined more slowly and will become increasingly harder. When bitcoin was created its monetary policy was based on the concept of artificial scarcity. When supply is constrained, that helps support its value (which in the end will be driven by the demand for it).

What are forks?

A fork occurs when new features are added to a blockchain, to deal with hacking, bugs, increase the number of transactions that can occur per second, and so forth.

Bitcoin Cash (BCH) was created out of bitcoin (BTC) to increase the block size capacity to accommodate more transactions. The idea is that it would improve is value as a means of exchange. A currency’s use as a medium of exchange is one of the two basic things that gives a currency value – the other being a store of wealth.

So, when BTC was forked, owners of BTC owned equal amounts of BTC and BCH. Each was subject to its own supply and demand considerations going forward, which is mostly a matter of demand since supply doesn’t increase much over time.

Bitcoin Cash has since been forked as well to increase the block size, so there is now Bitcoin Cash and Bitcoin SV.

How do forks occur?

Forks are basically software upgrades.

You take the existing code, which anyone can do given the code’s open-source nature, and modify it.

The BCH camp – i.e., entrepreneurs, developers, activists, etc., who unite around a certain idea – took the bitcoin code, modified it, created their own rules, and called it Bitcoin Cash.

It’s like if you wanted to create a new version of a particular type of software. If you knew the code of that software, you could copy it and make your changes to it and sell it, and the price would be a function of supply and demand.

How close are cryptocurrencies to being viable long-term investments and not merely speculative instruments?

Cryptocurrencies aren’t there in either of the attributes that make money worth what it is – i.e., means of exchange, store of wealth. To get a gist of each market it’s important to know who the buyers and sellers are, how big they are, and what they’re motivated to do. Cryptocurrency markets are chiefly full of speculators trying to take advantage of volatile movement to sell something at a higher price than they bought it.

Because of the limited transactional utility (i.e., you can’t use cryptocurrencies to buy much) and the volatility (i.e., limits its use as a store of wealth), there is no stable source of demand. Central banks obviously won’t touch decentralized currencies as reserves. Institutional investors don’t have use for them as currency hedges against monetizations when real rates become unacceptably low.

They don’t have the long-established track records of alternative reserve assets like gold, nor the track record that they’ll hold up during times of turbulence.

And even gold, which has been used as a reserve asset for thousands of years has its own host of challenges, such as the fact that it’s a relatively small, illiquid market compared to global debt and equities markets. It’s not a plausible alternative for vast amounts of debt wealth to shift into being about 1 percent of the size (though its price can move substantially in the event of such a shift).

Gold ownership throughout history has also been banished by governments from time to time, including in the US from 1933 to 1975 (some restrictions were repealed in 1964). Government crackdowns are always a real possibility on any alternative payments systems or wealth storage mechanisms.

Other things to ponder for the cryptocurrency investor

Other cryptocurrency concerns for the long-term investor (not necessarily the speculator or day trader):

– Is the technology secure and reliable?

– If used as part of a payment infrastructure or inter-application payments system, does it or can it create operational efficiency?

– Is it scalable? Can many people use it to improve its transactional utility?

– Is its value stable to improve its use as a store of wealth? (This is the stablecoin concept has caught on among some, including Tether and Facebook’s Libra.)

– How is the governance system? Is it fair to everyone involved?

– How’s the regulatory response likely to turn out? If you’re a government you don’t want these off-the-grid payments systems to exist.