Liquidity, Leverage, and Bull Markets

In this article, we’ll go through the general outlook for financial assets and factors related to the economy and portfolio construction. In particular, we’ll talk about bull markets primarily driven by central bank liquidity and how that builds leverage and risks into the system.

The three big forces

There are three big forces and equilibriums that drive the economy and markets. As there is an entire article covering the subject, we won’t go into excessive detail here.

But briefly, they are:

i) Economic capacity utilization can be neither too high nor too low (i.e., the inflation and growth trade-off)

ii) Debt growth must be in line with income growth

iii) The yield of equities must be greater than the yield on bonds, which must be greater than the yield on cash, and by the appropriate risk premiums

Economic capacity utilization

The economy is made up of three basic things: labor, capital, and commodities and raw materials

When economic capacity utilization is low, that means the unemployment is generally high, capital isn’t getting to where it needs to go, and there an underutilization of commodities and raw materials that go into creating finished goods.

That means central banks have great incentives to ease monetary policy in some form to get them going again.

When the unemployment rate is low, asset markets are pricey or in a bubble, and the cost of commodities and raw materials is relatively high, then central banks are more likely to want to slow down the economy by tightening monetary policy.

Traditionally, asset prices dip before the economy, and the economy dips before the unemployment rate rises.

Debt growth vs. Income growth

On the second point, debt growth cannot exceed income growth indefinitely.

More accurately, debt servicing cannot indefinitely exceed the funds available to pay it (e.g., income, new borrowing, asset sales).

When do we know when we’re at a tipping point where debt growth is reaching its constraints?

When interest rates hit zero or a bit below.

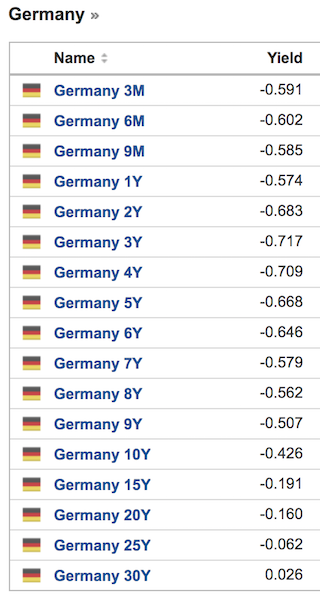

We are there practically everywhere in the developed world. Some countries are well into negative territory (e.g., Germany) and approaching clearly defined limits in terms of how low nominal interest rates can go (real/inflation-adjusted interest rates are a different story).

A euro currency based investor could put their money into a 30-year German bund and not make anything. Plus, a bond of that duration carries material price risk. That duration increases when yields fall.

German yields

(Source: investing.com)

Short-term and long-term interest rates can’t be pushed too far below zero because lenders no longer have much profit to work with. If they can’t lend profitably, they won’t do it.

When we get to this point – sometimes called “pushing on a string” – then monetary policy must be linked with fiscal policy. In the financial media, this is sometimes promoted as “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT), though there is nothing modern about it.

Linkage between fiscal and monetary policies is how it’s worked throughout history when monetary policy ceases to be effective on its own.

Fiscal authorities must target the money and monetary authorities must create the money. It is most effective when there are strong incentives to spend it, which is somebody else’s income, and getting that loop to feed on itself.

When private sector incentives cease working effectively, then the public sector takes more of a role in the distribution of capital in an economy. While some may not like this from an ideological perspective, it’s a type of practical evolution given the circumstances.

Cash vs. Bonds vs. Stocks

Lastly, stocks must yield above bonds, which must yield above cash. They must also have the appropriate risk premiums.

We always know what the rate on cash and various forms of bonds are. They are advertised in whatever one’s currency is.

This is basically what’s referred to when a yield curve inversion is mentioned in the financial media. Economies don’t work well when the yield on cash is higher than that of other financial instruments.

The way the capitalist system works is through people borrowing cash and using it to create productive investments that create value. When that’s out of whack, it eventually needs to be remedied.

If the safest asset yields the most, or other assets don’t yield enough, it will lead to hoarding.

At the same time, yield curve inversion can be healthy for short periods to avoid excessive speculation.

If people knew that cash could always be borrowed and put into stocks or other risk assets and it would always work, that could get out of hand.

Cash is the equivalent to short-term government debt, usually taken as the 3-month rate.

Bonds generally mean a mid-duration maturity of safe government debt, with the 10-year being a common benchmark. It’s popular because it essentially means what kind of investment return could you lock in over the next ten years.

There is price risk in that it’s always marked to market. But if held to maturity, you know what kind of yield you’ll get.

Fixed income is also a very broad asset class (credit is 2.5x-3x deeper as a market than stocks), so one can compare yields across various durations and credit qualities.

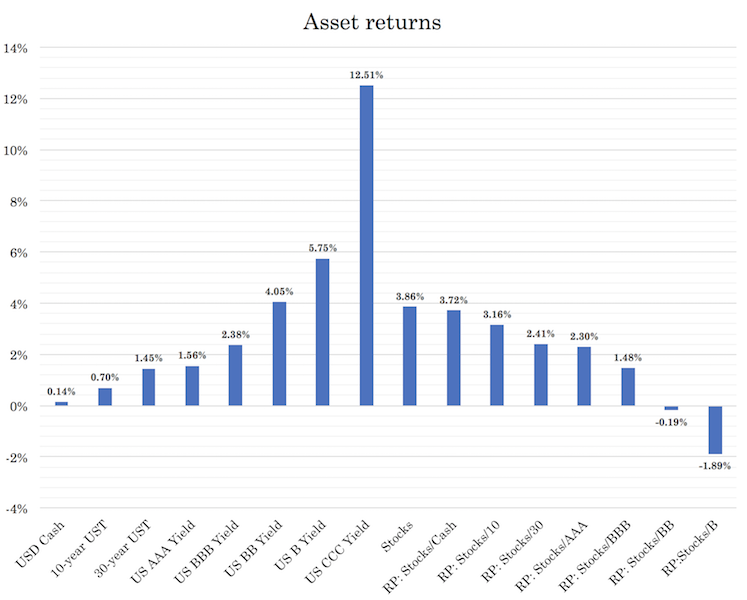

US projected asset returns and Risk premiums (“RP”) between asset classes

Stocks are harder to gauge because their cash flows theoretically go on forever.

The yield on stocks is a combination of:

i) the discount rate (a function of the rate on cash or a representative safe fixed income instrument)

ii) the risk premium

The price of a stock is a function of its earnings discounted back to the present. The sum of the discount rate and the risk premium represents this rate.

If stocks are about eight percentage points more volatile than the 10-year Treasury, then investors want extra return to compensate them for taking on this risk.

Sharpe ratios for asset classes are typically 0.2 to 0.3 over the long-run. This is the ratio of the excess returns over excess risks.

Eight percentage points multiplied by this 0.2 to 0.3 means investors expect to be compensated an extra 1.6 to 2.4 percentage points. The median is two percent.

If a 10-year bond is yielding 0.5 percent, that means it’s not out of the question for stocks to yield about 2.5 percent.

This seems very low, and it is compared to the past century in many developed markets where investors have received 6-12 percent, depending on where you go.

Central banks can potentially use their tools to try to inflate asset prices in nominal terms. But they are unlikely to be good in real terms.

In other words, people are unlikely to get a lot of extra real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) spending power from having a mix of stocks, bonds, and cash. There are higher yields elsewhere, but involves a mixture of political risk, institutional risk, FX risk, liquidity risk, and so on.

While a 0 percent return on cash, 0.5 percent return on bonds, and 2.5 percent return on stocks might seem low, it is a function of low productivity rates and stagnant growth in the working population.

And these will stay low for a long time.

Central bankers will attempt to ease these problems in the best way they can.

From history, one can see that most economic downturns are related to debt and liquidity problems. And these issues are dealt with, in one way or another, through an easing of monetary policy.

If you go back to the 1800s and look at how governments rectified debt and market problems, they always eased.

Depressions – when interest rates hit zero, not simply a “bad recession” – tend to not last indefinitely because in one form or another they figure out they need more money and credit in the system irrespective of what type of monetary system they’re on (i.e., commodity-based, commodity-linked, or fiat).

If they’re on an unconstrained monetary system (e.g., gold-based, bimetallic) and changing the convertibility of the commodity for the currency doesn’t work, policymakers will inevitably sever the tie with it.

As for the value of money, it is commonly depreciated.

Depreciations are also a zero-sum game. They essentially export economic problems to the rest of the world. Domestic wages remain the same, but they increase prices for imports and decrease prices for exports.

An excessive depreciation in a currency would incentivize other export-oriented nations to devalue their currencies as well to keep their goods competitively priced in the global market.

A depreciation can be especially risky when that currency isn’t in great demand globally or a lot of money has been borrowed in a foreign currency, like they commonly do in emerging markets.

A currency depreciation is good for stocks, gold, and commodities. These assets are priced in a certain amount of money per share, ounce, barrel, or other unit.

So, if you depreciate the currency by creating more of it, part of the dynamic is not that the asset is going up. Rather the value of money is going down, causing the price to go up in nominal terms basically as a type of contra-currency.

A currency depreciation is bad for bonds (and cash naturally, as it loses its value). Fixed income instruments involve providing a fixed amount of money paid back over time. If it’s in depreciated currency they become less attractive investments.

Policymakers typically also prefer cash and bonds to be unattractive when they want to ease to get a reflation in activity. It helps push people into spending and into the types of assets that can help finance spending.

Hitting the zero interest rate lower bound has never been a hard constraint even if it seemed like a barrier and a new problem when it happened.

This was the case in the 1929-1932 period in the US during the Great Depression and the 2008-09 period after the financial crisis when buying assets to lower long-term rates became the new policy.

Even if nominal interest rates can only go to around zero, the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) interest rates can go quite negative.

Therefore, it’s quite likely that nominal interest throughout the developed world – for a long time – will stay relatively anchored.

More of the focus will be on fiscal policy and money and capital flows will likely induce more volatility in real interest rates instead. (Real interest rates are simply nominal interest rates minus the inflation rate.)

That means shorting nominal rate volatility and being long real rate volatility could be a viable long-term trade.

The problem with overly easy monetary policy is that the value of money can end up so low that people lose confidence in it.

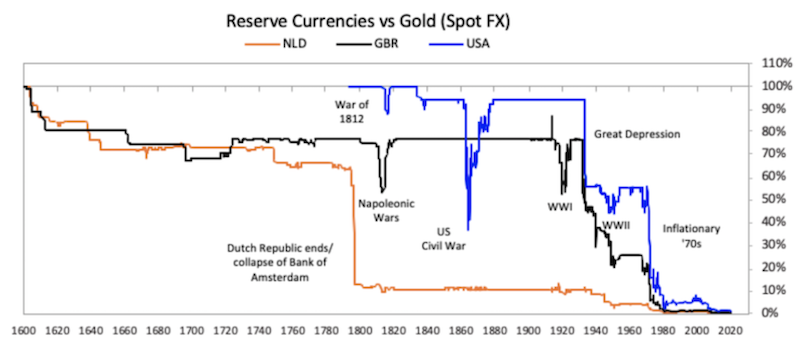

The USD is the world’s top reserve currency by a large margin (e.g., about 60 percent of global payments, debt, and FX reserves). It’s less of a problem for the USD and secondarily the EUR and others that are somewhat reserve currencies, like the JPY, GBP, and so on.

But it can be a huge issue in countries that pursue aggressive easing policies that have limited savings in their currencies. When there isn’t much demand for their debt, there have limited capacity to print.

The US can pursue the most aggressive easing measures, followed by the EU, then JPY and GBP to keep their asset prices high. China can take care of its own system.

On matters of currency risk

Too few investors focus on currency risk because inflection points in currency regimes happen maybe once or twice a lifetime in countries with reserve currencies.

Typically they occur when the currency has been devalued to a point where foreign investors no longer want to hold it (causing it to lose its reserve status and much of its value). Or a country undergoes inflation that can’t be controlled, forcing them to replace their currency with a new one.

In the latter case, they either retire the old currency and bring about a new one with a hard backing (commonly against gold) or take up the currency of an established nation, such as Ecuador’s dollarization in 2000. This effectively restricts what they can do monetarily, given the constraints to money creation.

Eventually, the claims on debts become too large relative to the amount of money available to settle them. This means the central bank has to change the convertibility of the commodity to money (if on a commodity-based currency system) or go off it entirely.

And the cycle repeats itself over the decades.

In the interim, central banks usually do a good enough job of raising and lowering interest rates to get money and credit into the system such that currency cycles are longer in duration than the business cycles that everyone is accustomed to.

The United States went through two big changes to its monetary system in the 20th century.

On March 5, 1933, President Roosevelt made the announcement of ending the link with gold and depreciating the currency to reflate the economy. That gave banks the money they needed to repay their depositors.

The same type of thing happened on August 15, 1971 when President Nixon said he was unlinking gold from the dollar (the relationship had been previously re-established in 1944 under the Bretton Woods monetary system). There were too many liabilities relative to the amount of gold available and there wasn’t enough gold to go around.

These big inflection points can be viewed when looking at the value of the dollar in gold terms (in 1933 and 1971). Gold is simply priced as the inverse of money. Sudden splits from hard money systems produced the biggest gains in gold, though it didn’t cause the dollar to lose its reserve status.

The US dollar and other developed market currencies will depreciate relative to gold. They have too much debt and non-debt liabilities (i.e., healthcare, pensions, other obligations) that will require large creations of money.

However, in free-floating exchange rate systems, we are not likely to see the big surges in gold’s price that we saw previously.

The outlook for asset prices?

Cash and nominal bond yields will be stuck at or around zero for a very long time in all developed markets.

They are closer to funding vehicles than assets. They have no real use for income generation purposes (outside potential trading vehicles if one expects interest rates to get even lower).

For positive yields on nominal bonds, one would have to take some currency risk and go to emerging markets or bet on riskier forms of credit. China’s bond market has positive yields and is under-owned relative to the country’s role in the global economy.

Some ETFs also provide this type of diversified exposure, such as EMLC.

For stocks, there is likely to be more differentiation.

In a zero interest rate world, owning the cyclicals is more risky, such as autos, heavy machinery, housing, and so on.

In normal business cycles, if earnings go down a lot, the central bank can lower interest rates to help get a bottom in these securities.

In a zero rate environment, this is no longer possible through the interest rate channel, giving them more downside.

Instead, the best stocks are likely to be thought in terms of what can be a good store of wealth.

What companies have earnings that are unlikely to be affected much in a recession?

That likely means companies that sell consumer staples, food, basic medicine, and so forth. These are products that people need to physically live everywhere in the world.

There’s also a case for buying “the innovators”. Which companies are on the frontier of innovation in society and are driving new productivity gains?

This can be things like AI chips, quantum computing, 5G, and information and data management. Other things will be mistaken as such (e.g., blockchain, electric vehicles).

Other investors have picked up on this and have bid up some of these companies (e.g., Nvidia (NVDA)) to sky-high valuations.

Returns will be low for a very long time

When cash and bond rates are zero, that bends equity valuations down to those levels as well.

A lot of liquidity has been pumped in by central banks and through fiscal actions globally, lowering the risk premiums of financial assets.

Asset prices are high to the point where a lot of nominal growth is going to need to be produced to justify their valuations, likely in the form of stagflation. Or else financial assets will need to re-rate back down.

Nominal growth is the sum of real growth and inflation. Real growth is the sum of productivity growth and growth in the labor force.

Real growth is not likely to amount to much, about 1-2 percent annually. That means more of the onus is going to fall on inflation.

There are plenty of deflationary forces out there:

– high debt

– higher global labor supply (India and China growing their middle classes)

– aging demographics and higher dependency ratios

– technological innovations tamping down on price pressures in labor and some goods and services

– lower rates and cheap capital making it possible for companies to pursue market share rather than profits

And central bankers in the US, Japan, and most of developed Europe haven’t seen much in the way of inflation since the 1980s or 1990s depending on the exact place.

Because the costs of not providing enough stimulus are so high, policymakers are going to press their limits on lowering interest rates, buying assets, and other liquidity programs until they reach those limitations.

Those limitations will come in the form of currency, balance of payments, and/or inflation problems.

Most currencies are likely to depreciate relative to gold. No developed market currency is that attractive in relation to each other with cash rates at zero practically across the board in all major currencies.

Are we likely to see economic cycles as prolonged as the March 2009 to February 2020 (11-year) expansion?

Economic cycles are generally a function of the central bank tightening monetary policy to control inflation.

The 2009-2020 economic cycle that went on in most of the developed world was a function of low interest rates. QE that started in March 2009 helped get a floor under the economy.

But the post-2008 measures also caused the economy to start growing again from a high debt base. That meant there was a lot of debt-related deflationary pressure and an economy that wouldn’t be able to tolerate much of an upswing in rates because of what it would do to debt servicing requirements.

The same is also true from mid-2020 forward.

This time, however, the labor market will take longer to recover. Industries like lodging, leisure, gaming, restaurants, and other service establishments will have issues with demand for several years.

When there’s a contraction in labor, that puts upward pressure on commodities and/or capital. Will that be inflationary?

How much deflationary impulse will be present from the continued growth in overseas labor markets such as China and India?

Central banks have no traditional power to counteract a downturn with adjustments of short-term interest rates and QE.

More will be needed from the fiscal side, but that’s inherently a political process and that’s more divided than normal.

The US-China factor

China is the largest foreign owner of the world’s top reserve currency – the USD (in the form of Treasury bonds).

It also has more conflict with the US. In combination with the US deficits that is going to necessitate a lot of printing of dollars, the USD is very likely to depreciate relative to something like gold.

It’s also likely to depreciate relative to the yuan over time as their incomes get more in line with those in the US.

The US has a GDP per capita of 6x that of China’s as of 2020. Chinese incomes aren’t going to get up to US incomes anytime soon, but they will get closer together.

Moreover, with the US’s conflict with China is going to be around for a long time. Both want to be the global superpower and protect their own interests. They will continue to butt up against each other.

Issues such as IP theft, forced technology transfer, government subsidies, market access, market competition, global spheres of influence, and cyberespionage just don’t go away if they’re being ignored.

It’s just following the standard template of how geopolitical conflicts emerge going back centuries when an ascendant power is a threat to the influence of a pre-existing dominant power.

It starts with trade, moves to capital, then becomes geopolitical in most other ways, and usually, but not always, ends up in a physical confrontation/military engagement (12 out of the past 16 times going off the past five centuries).

China, to be defensive, will increasingly not want to hold US bonds. It will want to diversify to other countries and to alternative stores of wealth like gold.

The threat of capital flow disruption between the US and China will become more of a theme if history into these types of conflicts is any guide. The US can unilaterally cut off capital flows to China, impose sanctions on non-US financial transactions with China, freeze payments on debts owed to China, and so on.

Will central bank actions to fix economic crises (i.e., low rate, asset buying) just create more of the same debt problems?

Pushing a lot of liquidity into the system helps to push up asset prices, push down risk premiums, and lower market volatility.

The combination of progressively lower market volatility and shrinking risk premiums creates more incentives to take on leverage to obtain the desired return on equity.

This builds leverage. And sometimes it builds leverage in different sectors that are not well controlled by policymakers (e.g., housing, tech).

With “unlimited” asset purchases from central banks, this leads to more leverage in financial assets with all the liquidity in the hands of institutional investors all over the world.

This spills over into all types of asset classes. You see it in the high-priced real estate market as well as the art market, as investment managers bid up risk assets and use their fees to buy up luxury goods.

Following the 2020 bust, the wave of liquidity that sent government bond, corporate bond, and some equity/ETF products yields down (i.e., from central bank asset buying) meant everybody (who had the means and a risk appetite) had to get money invested.

That’s led to a big shrinking in risk premiums.

In these types of environments, practically anything that has a higher yield gets bought up against something with a lower interest rate.

When market volatility falls, this becomes extrapolated forward. They believe price volatility is likely to stay low. Therefore, yield becomes the more important factor.

This develops short positions in low yields assets (from borrowing in them) against the higher yielding assets.

Leveraging up occurs as investors believe they can have larger positions with the same amount of risk.

That also means more financial engineering in private markets, such as private equity. Private companies can obtain very high multiples on revenue with funding from venture capital and PE firms.

Some of these companies want to go public even if their financial health leaves a lot to be desired, they lose money, and it’s not certain how they’ll make a profit to justify their massive valuations.

With rallies to new high and P/E ratios extremely high relative to history, are investors ignoring warning signs?

Inevitably there are hiccups in any market. But when you have liquidity flowing and there’s no tightening, you usually aren’t going to have major problems or big price drops.

There might be hiccups related to concerns of inflation picking up, which might lead central banks to think about tightening sooner than what they think (and relative to what’s discounted into futures markets, which affects the present values of assets).

Some debt problems in certain pockets of the economy might also cause a concern, similar to subprime lending in February 2007 before the major problems came to a head 1.5 years later.

A big unknown is inflation. Will the reduction in the supply side of the economy (perhaps temporary, perhaps offset by overseas labor or technology that reduces the types of labor needed in an economy) lead to supply-side related inflation?

High asset prices, increasing leverage, some misallocation of capital into bubble companies and bubble sectors will mean that down the line there will be a lot of volatility.

Risk of another recession in the US and/or other developed markets?

Things like natural disasters are very hard to predict and bad ones come around very infrequently in relation to the span of a lifetime.

When a lot of liquidity is available and there is no concern about inflation, traditional recession risks are very low.

This can eventually turn into inflation risks or financial stability issues, but that comes down the line.

Recent US recessions did not come because of an attempt to bring in inflation. Two came from financial instability (i.e., bubble in tech companies in 2000-02, subprime lending in 2007-09).

Another issue is social and political conflict.

Rising income inequality and shifting labor needs of an economy leave people behind. The biggest political divide in the US is urban versus rural households.

Urban areas tend to have quality services and technology jobs. On the other hand, rural areas that don’t have these jobs and are often reliant on “old economy” industries (e.g., manufacturing) are increasingly seeing these jobs get offshored, hollowing out these areas.

This is increasing issues related to higher rural unemployment, higher suicide and premature death rates, higher opiate usage, and so on.

Those who own financial assets have benefited from these booms, with only 1 percent of the population owning 40-50 percent of the total wealth. There comes a point where people believe the system isn’t working well for enough people and demand change.

This bleeds over into social tensions and new political movements, which become more extreme. Political compromise is less likely, leading to more conflict within countries and also between countries.

Protectionism and drawing a hard line against countries that are “taking” these jobs resonates with more rural, working-class citizens.

Portfolio positioning in times of stretched equity markets

Yields on stocks in the 2-4 percent forward return range are not attractive relative to their returns.

Because cash is so bad at minus-100bps to plus-25bps everywhere in the world, getting an extra ~4 percent premium on stocks isn’t terrible. It’s about a 0.27 Sharpe ratio, which is within typical risk/reward parameters. But it’s not attractive relative to their risks.

As risk premiums decline and leverage builds and certain bubbles inflate (e.g., Tesla at a $500 billion market cap), it becomes increasingly something you don’t want to participate in or even bet against.

Some parts of the stock market are similar to what was seen in “dot com” stocks in 1998 to early-2000.

Many types of trades are essentially a skewed bet on credit spreads narrowing – e.g., long stocks, long credit, long emerging markets.

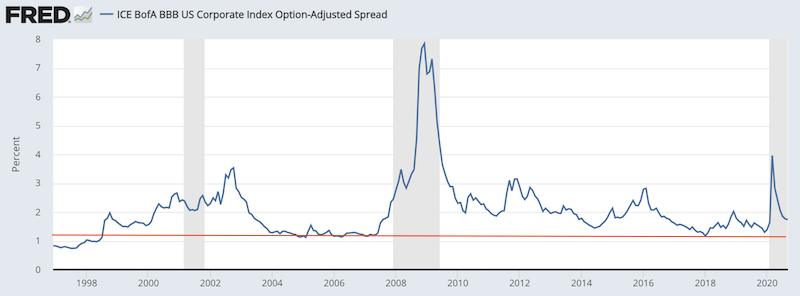

Credit spreads below a certain level can be sustained for years, especially with supportive central banks and no trigger to cause a downturn in the economy. But it becomes a riskier situation as leverage and risk-taking build.

For example, BBB spreads (over similar duration Treasuries) are tough to push much lower than one percent.

US BBB spreads are hard to sustain <1.2 percent

(Source: Ice Data Indices, LLC)

The risk relative to the reward of safe government debt (that the government can always pay in nominal terms) versus somewhat risky corporate credit isn’t much at just 120bps or less.

Shorting credit spreads means paying that spread and making money when credit spreads widen in excess of the annual compensation paid.

It’s a type of anti-carry trade that benefits when markets decline.

Stocks, gold, commodities will tend to benefit but not so much bonds

Pressing against the zero lower bound on interest rates and governments needing to create a lot more money is positive for gold and commodities. It is bad for cash and nominal government bonds.

The possibility of higher inflation popping up from this large stimulus means inflation-linked bonds can be good to own in some quantity.

The investment management business is increasingly less distinguishable than other types of businesses and vice versa.

In the past, traders would typically specialize in equities, credit, and so on. While that form of specialization still exists, now it’s heavily geared toward those who can construct the best portfolios.

These portfolios can include traditional financial assets, private businesses, hard assets, securitized assets, derivatives, and so forth.

Financial engineering and derivatives enables managers to break up investments into different building blocks and components and build them back up into more efficient portfolios with higher return per unit of risk relative to just stocks or credit only.

It’s also a technological change that will probably make it more difficult for new hedge funds to compete.

Are those not participating in the stock market missing out?

There are always going to be times when the world around you is doing things that you don’t want to be participating in and, in fact, even bet against it.

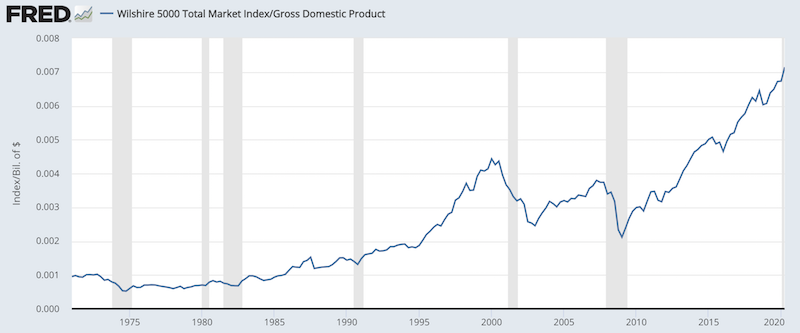

Stocks as a percentage of the US economy have grown to levels never seen:

Stocks/GDP (sometimes known as the “Warren Buffett indictor”)

(Sources: Wilshire Associates)

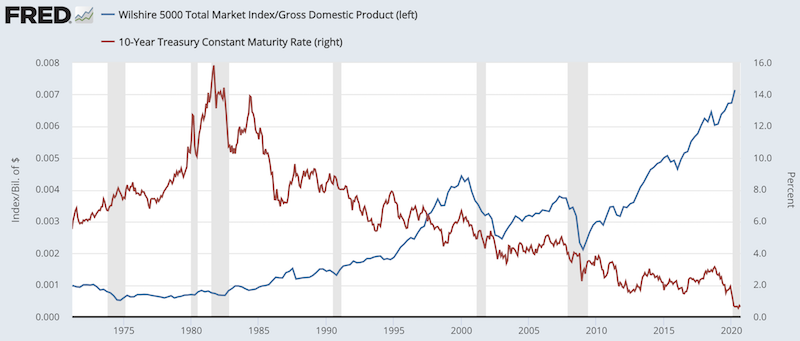

Much of this has to do with the progressive lowering of interest rates (red line) since Q2 1981 to increase their present values (i.e., their prices):

Lower rates are responsible for much of the rise in stocks

(Sources: BEA, Board of Governors, Wilshire)

In certain parts of the market, the liquidity flowing in from central banks is producing bubble reminiscent of the late 1990s.

Even if stocks are a bad bet at 3-4 percent forward yields (i.e., P/E ratios of 25x-33x), then can become even more extended.

The biggest mistake in trading and investing is almost implicit in this type of question. Most assume that the recent past is a representative of the future. The good times become extrapolated even when higher asset prices typically means lower forward returns.

When the central bank lowers interest rates, there is real wealth being created through higher asset prices and higher credit creation (so long as such debt is used productively). But there are defined limits to how low those can go, and we’re right at those constraints.

Just because a recent period hasn’t been up to expectation doesn’t mean a trader/investor has to change what they’re doing.

The real question comes down to whether their judgment is sound or not.

Hedge funds and low returns

Investment managers tends to have high betas to the equity markets. There’s a bias to be long stocks and leveraged long. So when those go up, the whole industry tends to do well.

And because of the amount of liquidity flowing into the financial system from March 2020 to June 2020, the stock market had a very fast recovery.

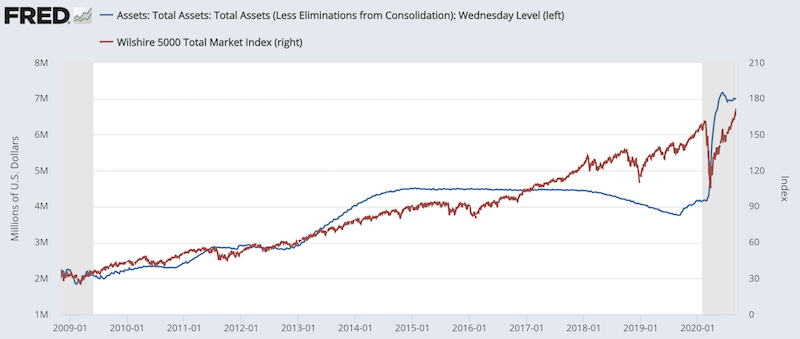

The graph below shows US stocks against the Fed’s balance sheet. The more assets the central bank buys, the lower their yields get, forcing more private sector participants into the stock market to get the types of returns they need or want.

Add liquidity into the financial system, it’ll get into assets

(Sources: Board of Governors, Wilshire)

The 2020 related downturn that led to the explosion higher in the Fed’s balance sheet dented earnings. But at the same time, the liquidity pushed in bid up the prices of everything, making everything overvalued.

Even while the investment management industry is too large, there is a greater differentiation of managers at the same time. Most good managers are closed to new investment and there is differentiation on fees.

Active management will continue to become more technologically intensive. In the end, it all comes to what kind of value they provide even if it can take a very long time to determine it.

What’s the effect of having ‘too many’ hedge funds and institutional managers?

Hedge funds, private equity, and institutional funds of all sorts affect liquidity and will be affected by liquidity.

Most of these types of investors tend to hold a lot of the same positions.

For example, during 2020, companies with positive earnings that had their incomes disrupted in the present didn’t receive the same benefit as those companies whose cash flows are discounted to come more in the future.

This meant “value” suffered to a greater extent than “growth”. Companies like Nvidia, AMD, Tesla, Square, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google all took off relative to value, especially cyclical value.

These are all crowded trades, trying to buy the “high yield” assets while selling the low yield asset particularly when borrowing is free or close to free.

Many new investors are also rushing into these names, which is one of the classic signs of a market bubble.

The next time liquidity starts to dry up (e.g., central bank tightening to fight inflation, a separate shock to the economy), there will be an unraveling of debt much in the same way as previous crises.

The more these types of trades get pushed and the more credit spreads narrow, the more you don’t want to participate and have a bias for taking more “anti-carry”-like trades.