NIRP: Coming to the US?

This article was published on May 14, 2020.

Negative interest rate policy, commonly abbreviated NIRP, is employed in other parts of the developed world outside the US.

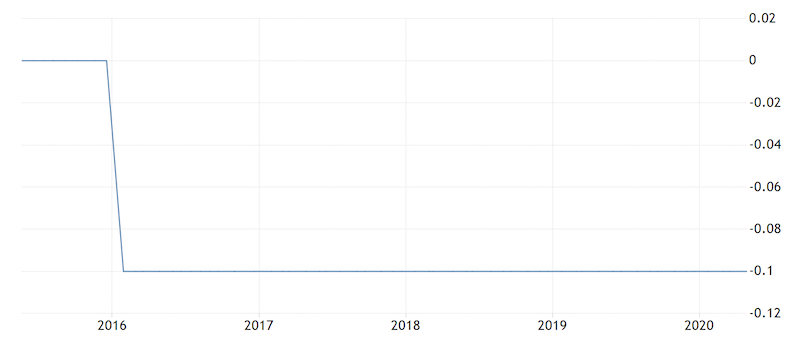

Japan has its front end rates at minus-10bps (0.1 percent) and has been that way since early-2016.

(Source: tradingeconomics.com)

The euro zone’s deposit facility rate has been negative since 2014 and was dropped to minus-50bps in September 2019.

(Source: tradingeconomics.com)

US Federal Reserve officials have pushed back on the notion that they are considering NIRP ever since the financial crisis.

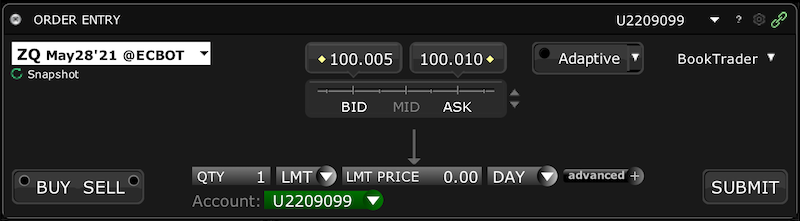

But recently, fed funds futures, the interest rate product that allows traders to make bets on the future movement of the overnight lending benchmark, recently implied that negative interest rates were more likely than not, based on a price trading above 100. (The implied rate is 100 minus the price of the contract, and is based on a weighted average of the price over that calendar month.) Fed funds futures are tradable under the CME code ZQ on some brokers, like Interactive Brokers.

(Source: Interactive Brokers)

Is the market genuinely implying NIRP?

Prices in the market are what they are for various reasons. Sometimes you just see one side or leg of a trade that’s “distorting” the market (especially in options markets).

For example, some rates traders could go long fed funds futures as one leg in a steepener trade, betting on the entire yield curve getting steeper by going short a duration longer out on the curve.

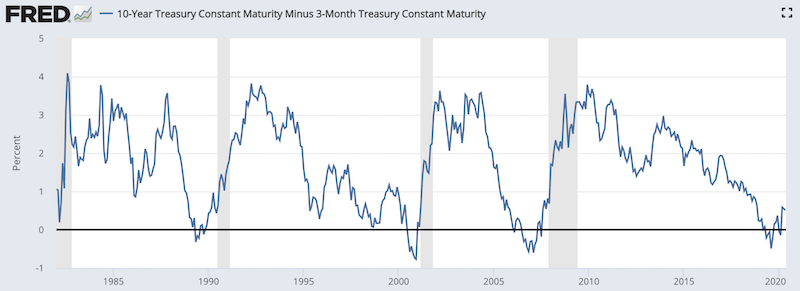

Because we’re now in a very deep economic downturn that will take a while to recover from, the rates curve is very flat. This means traders are pessimistic about future interest rates rising much.

The graph below takes the 10-year US Treasury rate minus the 3-month rate. The spread is near zero, which tends to be the discounted scenario when economic prospects are bleak (note how the spread tends to go negative before recessions).

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

What would US NIRP do for the rest of the world?

If the Fed were to take cash rates into negative territory, it would do a favor for the rest of the world.

A lot of debt in the world is denominated in US dollars because of the network effects associated with so many people buying, selling, borrowing, and lending in a particular currency. Globally, we know that US dollars are 62 percent of foreign exchange reserves, 62 percent of international debt, and 57 percent of global import invoicing.

Will it weaken the US dollar?

A lower rate would expect to depreciate the USD because the currency would yield less and would thus be less valuable to own, holding all else equal.

But it’s not that straightforward. Given NIRP has been employed in other developed markets, such as Japan, Sweden, and the euro zone, it’s not clear that a currency depreciates after the introduction of NIRP.

For example, USD/JPY went from 120 to 100 (JPY appreciating) after the Bank of Japan introduced negative rates on excess reserves in 2016.

The EUR and SEK weakened once NIRP was priced in ahead of its implementation, and also weakened after.

But if the Fed wants to weaken the dollar it will need to contend with the extra Treasury issuance. Because of the holes in incomes and balance sheets brought about by the downturn in 2020, the US federal government has had to spend a lot of money to compensate, eventually likely north of $5 trillion.

They don’t have that money. The government is not a rich entity or a bottomless pit of wealth. Money itself is intrinsically worthless. Income is a function of productivity, which is where wealth comes from. Money is simply a means of exchange and can be a wealth storehold, such that people don’t literally have to go around exchanging services for services, goods for goods, or services for goods. Money is simply an intermediary that simplifies a transactional exchange.

The government is just a collection of citizens and in exchange for certain services, the government takes a fraction of what is generated from their productivity, usually through income and consumption taxes. When they don’t have enough money, they need to borrow it. That means issuing bonds.

Who buys the bonds?

There isn’t enough private sector demand for it (domestic or foreign), especially as the rates on it are around zero. So, it’s up to the Fed to buy it with newly created money.

To weaken the dollar, the Fed will need to keep pace with this issuance. When there’s an excess supply of debt, that pushes prices on the debt down, and yields up. What’s bad for bonds isn’t necessarily bad for the currency.

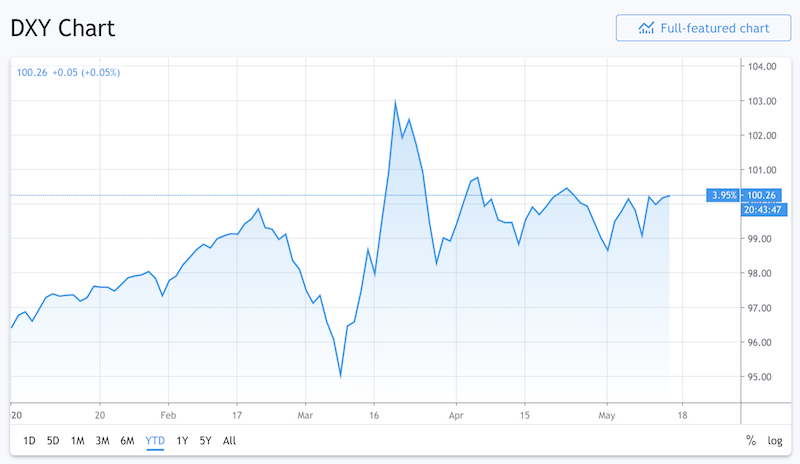

When there isn’t enough of a supply of a currency, it pressures the currency upward. Because entities globally don’t have enough dollars, that pressured the dollar higher during the virus-related crisis.

(Source: Trading View)

Eventually the dollar will weaken when either enough money has been “printed” to meet demand for it or restructuring and bankruptcies will reduce the need for dollars because debt’s been defaulted on.

If the Fed could “out-print” new Treasury issuance, new private sector demand (due to downturn-related needs), and other central banks (in relation to FX volume), then the Fed can realistically begin weakening the USD.

NIRP itself, or potential NIRP, is a not “cure all” to the strong USD.

And USD weakening is also a matter of relative to what it’s depreciating against?

The other two main reserve currencies – EUR and JPY – have similar financial issues as the US (i.e., a lot of debt and long-term obligations that will never be paid off) and also bear near-zero, zero, or negative interest rates throughout their sovereign yield curves.

What it is likely to weaken against over time is an alternative currency that’s a traditional hard backing and serves as no one’s liability (e.g., gold and some other commodities that are not subject to large swings in demand). These alternative should not, however, be a big part of one’s portfolio as they are simply cash alternatives.

Will NIRP plus a lower US dollar help further raise bond prices?

Lower rates also help with refinancing (or lower automatic payments for variable-rate debt).

While it would help ease debt burdens, it would be a negative for domestic savers in USD and for USD banks. Lower interest rates make cash a little bit less attractive to hold. But the policy isn’t likely to push investors into risk assets, like stocks and lower-quality corporate credit, by itself if their reward relative to their risk aren’t attractive in absolute terms. Investors will still view those assets as risky.

The massive issuance is not likely to generate a sell-off in the bond market – namely, prices lower, yields higher.

If the Treasury issuance is larger than the Fed’s supply of money provided to the economy, USD liquidity conditions will tighten (i.e., dollar scarcity). If the scarcity observed in March and parts of April arises again, then USD bond yields typically drop due to the hit in financial conditions. In other words, investors demand safety and liquidity in the world’s dominant reserve currency and bond yields decline.

For foreign investors, there’s been a drop in USD hedging costs. Accordingly, the USD bond market is now comparable or better than the EUR or JPY markets for, e.g., Japanese investors. (For a further rundown of buying foreign bonds and the currency hedging process, please see Negative Yielding Bonds – Who Buys Them?)

If USD hedge costs remain low and the JPY 10-year is kept at around the 0 percent mark by the BOJ, Japan’s yield curve control will essentially spill over into the USD bond market as well.

This could help support longer duration USD bonds.

The Fed recently came out and announced that the federal government will need to do more to support the economy. Based on $2.9 trillion in current spending and over $5 trillion worth of losses so far in the US alone, it’s likely that Congress will need to provide even more spending to fill the gaps.

With all this extra future issuance, the Fed will need to keep pace to hold down yields, weaken the dollar and give a lift to the global credit market.

Accordingly, there is still a lot of Fed QE to go before USD scarcity concerns are alleviated to allow for easier financial conditions. Fed printing will need to be on a significant scale to provide a tailwind to emerging markets and so that global economic “reflation” can occur. Some of it still depends on the virus and how that impacts economic activity.

The US Treasury market will be a heavily centralized market, much like the Japanese and euro zone government bond markets. While some bonds can be held for safety, liquidity, and diversification purposes, yield is not among their attributes. Central banks need to hold cash and bond yields down to get investors into assets that will help finance spending in the real economy.

What do various Federal Reserve central bankers think of NIRP?

The Fed communicates to the public to help inform what their plans are. This is known as forward guidance and helps avoid surprises to stabilize the capital markets.

After fed funds futures went negative, several central bank officials came out to refute the idea and pushed back against market speculators.

Per the Bloomberg headlines:

- BULLARD: NEGATIVE RATES NOT GOOD OPTION FOR U.S.

- KAPLAN: ‘I WOULD BE AGAINST NEGATIVE INTEREST RATES’

- KASHKARI: FED POLICYMAKERS HAVE BEEN ‘PRETTY UNANIMOUS’ IN OPPOSING NEGATIVE INTEREST RATES

The Chicago Fed earlier put NIRP at the very bottom of the “central banks tool kit”.

The US economy is highly financialized and banks rely on positive lending rates on short-term assets to help their profitability. Going into negative territory throws this for a loop.

But it’s another one of those things if things get bad enough everything is on the table.

At one time, zero percent interest rates seemed implausible as the borrowing and lending relationship was essentially broken (“free money”).

Buying financial assets was controversial back in the 1930s during the Great Depression (when the Fed first used it to lower policy rates further out on the curve) and again in 2008 during the financial crisis.

After that they dip into lower-quality forms of collateral beyond government debt.

There’s coordination with fiscal policy, monetizing debt, or even putting money in the hands of spenders, as a third general form of monetary policy.

The Fed will have new data points coming in and will need to think of ways to weaken the USD. Import prices – a function of a strong dollar – are putting downward pressure on CPI core goods inflation and will continue to for the next year or longer. A higher USD versus its main trade partners will add onto that downside pressure.

Headline inflation will fall, which includes volatile commodities prices, which have undergone their worst route since the 1930s.

Core inflation, which largely excludes volatile food and energy prices, will fall sometime after.

Inflation targeting is the most foundational central banking practice. It is always set to a low, positive targeted figure or range.

It is never set to a negative value as this generally means prices, production, income, wages, and spending will typically contract. This is because deflation is usually indicative of a credit contraction, and debt service payments exceeding incomes on a pervasive level in the economy.

Even when deflation is benign in nature – namely, aggregate supply exceeds aggregate demand – this signals that output, wages, and spending largely aren’t being maximized.

Inflation also helps to lower the real interest rates being paid on fixed-rate debt, which is most debt in an economy.

If someone has a loan charging four percent interest, the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) interest rate on that loan is two percent if inflation is at two percent (4%-2% = 2%), a typical target of most developed markets. If inflation is negative-two percent, the real interest rate is six percent (4% – -2% = 6%). Creditors would be at a big advantage relative to debtors. When debt levels are high, deflation can be particularly undesirable relatively to a low, stable rate.

Virtually everyone, including the Fed, is currently incentivized to support measures to weaken the US dollar and help push up inflation and inflation expectations. That alone is enough to not rule NIRP out completely.

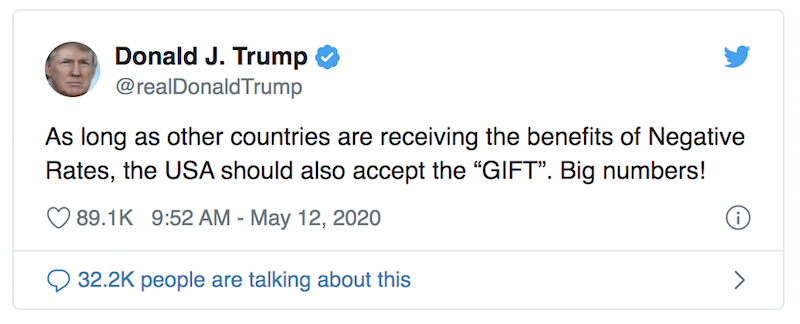

The president’s take

President Trump always prefers easier monetary policy and this can be taken from a couple different angles.

Why, specifically, does Trump want negative interest rates from the Fed?

a) Trump is heavily focused on being re-elected.

Lower interest rates typically help support economic growth and typically go together with a rising stock market and other financial asset prices. A better real economy and a better financial economy both contribute to increasing the odds of the incumbent candidate being re-elected. Accordingly, getting lower interest rates will help him achieve this goal.

If his primary aim is re-election he may be less vocal about wanting easier policy following November 2020. The economy may also begin to recover after a terrible Q2 and so easier policy may not be necessary.

Nonetheless, negative interest rates may still be of interest for him in terms of his personal view of how to help maximize the economy’s support throughout his prospective second term and for legacy reasons.

b) Trump has been a real estate developer for most of his life. Real estate is heavily about obtaining loans and credit at the cheapest possible rate to maximize your spread between what you’re paying to the lender and your return on the project. This is true for all businesses.

Trump has also asserted that he believes US interest rates should be lower than Europe’s and Japan’s because the US is “prime” relative to them. This is an application from the business world where more creditworthy borrowers should get lower interest rates.

But interest rates at the sovereign level are a function of nominal GDP. If one country’s nominal GDP is higher, it’s also expected that their interest rates will be higher accordingly.

To Trump, lower rates are hardwired as always a good thing in helping him in his business and in achieving his political goals.

Regarding Trump’s mention of “big numbers” that NIRP would prospectively let loose, he probably means the stock market.

Final Thoughts

From a variety of Fed officials, negative interest rate policy (NIRP) is unlikely, and the base case is that the overnight US benchmark rate will not go negative over the next year.

But given the damage to the global economy to incomes and balance sheets due to events in 2020, virtually everything is on the table as policymakers try to save the system.

There could be yield curve control (YCC, also known as yield curve caps), which is similar to what the Fed did during the 1942 to 1947 period to help fund World War II.

There’s a bevy of new liquidity programs and could be more, if necessary. Consumer confidence will be slow to return in many respects, which will have a lingering effect on many businesses.

Buying stocks could be on the table, though it’s legally dubious for the Fed to do so. It’s also uncertain what it would accomplish. The federal government may take stakes in certain companies that it wants to save for economic or strategic reasons, and it is buying bond ETFs (which are equity products) much like the BOJ has already done. But buying equities isn’t high up the list at the moment.

Negative interest rates are part of that menu of options.

Answers on negative interest rate policy are unlikely soon

Nonetheless, we’re unlikely to get answers in the short-term, though traders are always thinking ahead and/or putting on trade structures that could skew certain markets.

Markets currently discount a bad Q2’20 (when this is being written), but a gradually recovery in Q3, Q4, and in 2021. The stock market has bounced 30 percent from the March lows on the expectation that earnings will begin to recover, on aggregate, in 2021 and be more or less back to normal in 2022.

If there are extra waves of the virus and economic shutdowns restart and become more elongated, then the central governments (both fiscal and monetary arms) will be called on to do more and cooperate with each other.

Countries with reserve currencies have more capacity to help out than those whose currency is much less demanded.

As traders buy back into the equity markets, buying fed funds futures acts as a natural hedge. If stocks decline due to economic concerns, this usually means increased odds of lower short-term interest rates as the central bank becomes boxed in to providing relief.

But it’s also an assumption that the central bank will actually use negative interest rates as a tool. They haven’t gone too severely negative in terms of the discounted expectations, but some traders believe it’s worth the reward relative to the risk to take a shot at the trade.

Going down to zero interest rates is a no-brainer – technically hitting the middle of the 0-25bp range – but negative has never been tried before in the US.

The Fed could also address the effective fed funds rate drifting down to zero (from the middle of the 0-25bp band) by adjusting the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER). This wouldn’t impact the likelihood of setting the fed funds rate into negative territory.

Naturally, Fed officials want to push back on the market pricing and have en masse through public statements to avoid the possibility of disintermediation in the banking sector – i.e., negative profitability outcomes from turning the lender and borrower relationship the other way.

Such bank disintermediation has plagued the euro zone economy through disincentives to lend. According to the data, negative rates haven’t spurred that much additional credit creation on the margin in the euro area. Northern Europeans have a lower propensity to borrow than other cultures, while southern Europeans see higher sovereign yields and less robust health in their banking sector.

It’s brought similar issues to Japanese banks. The US economy is more financialized than each of those economies.

Can the market force the Fed’s hand?

Markets are always priced based on a discounted view of the future. The nature of the discounting process is that if the thing expected doesn’t occur or transpire in the way expected then it leads to a repricing of financial assets.

Central banks have large authority over where asset markets go. They control a large part of the liquidity in an economy because of their monopoly on money creation. They are responsible for creating cash and influencing the credit creating capacity of the economy.

This is why investors and traders pay such close attention to them and why such subtle variations relative to expectations can cause material changes in asset prices. Moreover, when interest rates decline, the duration of assets lengthens, making them more sensitive to their changes.

If markets expect lower rates but don’t get them, then this decreases asset prices through the present value effect.

Lower financial asset prices have a feed-through effect into the economy. The financial system is what provides the money and credit into use for the real economy to use as a means of exchange (and/or can be used as a store of wealth).

This forward pricing for interest rates can, in some way, box the Fed into either following through on more stimulus or risk another repricing in domestic equities. This would further tighten financial conditions.

Accordingly, the Fed cannot entirely dismiss what the market thinks without repercussions. This is also why many central banks look to have officials with experience in the capital markets because of the important tie-in between the economy and financial markets.

Conclusion

Making interest rates negative via an official negative interest rate policy (NIRP) will make cash a little bit less attractive to own, and buying assets (i.e., QE/asset buying programs) will make bonds a little bit less attractive.

But negative cash and bond rates are not going to drive investors and savers to buy the type of assets that will help finance spending in the real economy. This is part of why Fed officials have pushed back on the idea and why many investors are of a similar persuasion.

Asset buying and negative rates can push asset prices somewhat higher. But at the same time, investors and savers will still be inclined to save and lenders and borrowers will still remain cautious with each other in the types of deals that they make.

There’s a limitation to how much further stimulus the rates and bond channels can help create because they can only go so negative. Rates at rock-bottom levels is an indication that you can’t push a debt cycle much further.

They’re at or approaching those limitations throughout the developed world.

No longer can central banks simply ease short-term or long-term interest rates to get money and credit into an economy. Instead, it will increasingly fall on the government to spend the money to bring up nominal growth and get credit flowing again.

At this point, it’s unlikely that the US will do negative rates and will stick with traditional purchases of bonds and credit.

Lowering the reserve rate below zero doesn’t necessarily have any effect on the deposit rate. And if there’s no effect on the deposit rate, then there’s no stimulative impact on banks’ funding costs. As a result, you aren’t increasing banks’ willingness to lend, the credit creation capacity of the economy, and therefore no tangible impact on aggregate demand/output.

Negative interest rates can actually be contractionary to the money-creating capacity of the banking system when taking into account the agency costs between banks and their creditors.

So, instead of going below the zero-bound, they plan to buy assets to target interest rates further out. In the future, it could mean things like a more direct “helicopter money” money program where the Fed will issue currency and put it directly in the hands of consumers – namely, skirting the financial system and bond market altogether – and tie it to spending incentives.

Super-low real and nominal interest rates are ultimately bad for currencies to which they’re relevant.

Such matters about money and debt creation in excess of income and productivity lead to questions about what’s the value of money and what are good alternatives if the yields on cash and financial assets become unacceptably low?

These are longer-term questions and not on the immediate minds of most policymakers, economists, or investors. But there is a long-run cost to such measures even if they’re the most palatable option currently.