Zero Commissions: Where Brokers Go From Here

With the recent surge in brokers going zero commissions, more traders are celebrating being freed from perpetual costs that eat into their returns. Controlling trading transactions costs is important for all different types of traders from small savers to large institutional funds. These costs are very different depending on size, strategy, market, time horizon, and other such factors. For retail traders, the cost of a trade is mostly in the size of the commission, making a “race to zero” a favorable development for customers.

The beginning of zero commissions

Robinhood popularized zero commissions to attract market share. It also built its business through a mobile app with a clean interface that made saving, investing, and trading “on the go” or for general convenience a huge hit.

It appealed heavily to younger demographics who typically save or invest smaller sums of money and can’t afford the traditional $2-$10 cost per trade that can materially eat into returns. Even $1 per trade is a lot to pay for a $100 trade. That 1 percent cost per month adds up to 12 percent per year. You’re not going to get 12 percent per year indefinitely from the market passively investing your money.

For some types of traders, any type of commissions on what they trade can make a broker unviable. This has spawned various inexpensive investment management apps in addition to Robinhood, such as Wealthfront, Betterment, and Acorns. It’s also pushed traditional passive investment managers, such as Vanguard, Fidelity, and Blackrock to reduce their expense ratios way down to nothing or almost nothing. Traditional brokers, including Schwab and E*Trade, also lowered their fees down to zero on their most commonly traded instruments to try and keep market share.

How do these ‘zero commissions’ brokers make money?

Robinhood, as many know, earns money by selling order flow to firms such as Citadel Securities and Virtu Financial. These firms, in turn, generate revenue by making markets (providing liquidity) in various securities.

In the industry at present, commissions are three times as large as fees generated from order flow (some $600 million versus $200 million). It’s not a big source of revenue, and certainly not big enough to offset the loss of commission revenue, but still a way to help compensate.

Why do market makers want order flow?

Retail traders tend to be less informed of events going on the markets and also don’t trade in sufficient size to move markets. So, market makers are likely to make money by trading against retail order flow.

Retail brokers can then take the money they make from selling order flow and pass that along to the customer by giving them better execution for their trades – a perk to attract new customers and keep existing ones – while also keeping some for themselves.

How will brokers make up for lost commissions revenue?

They will need to increasingly become more like banks. In other words, they will need to take more credit and duration risk.

Zero commissions is a way to attract more market share. That attracts in cash. Brokers will take this excess cash (that clients don’t use to trade) and invest it in securities or lend it out.

There is also an emerging trend with respect to “cash management” accounts. These are a type of bank account that is neither a checking account nor purely a savings account.

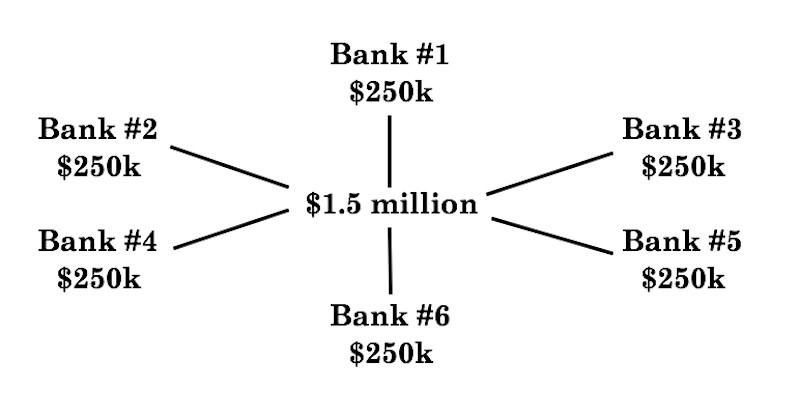

Cash management accounts are similar to a savings account, but client money is swept from the account to various FDIC-insured partner banks (for those operating within the US). By partnering with multiple banks, this allows them to get the insurance to several multiples of the standard $250,000.

For example, if a broker partners with six different banks, the insurance on the account goes up to $1.5 million (six multiplied by $250k).

While commissions have historically been a big part of brokers’ revenue models, the idea is that no longer being able to skim off trade volume is fine if it helps get control of someone’s savings and get them on their various banking products as well. This can mean checking, savings, and/or “cash management” accounts.

Robinhood, in particular, which benefited heavily from its zero commissions policy, had to respond now that traditional brokerages are challenging it on its own turf. Many other brokers also now have mobile apps to trade on. So, this competitive advantage has been eroded as well. This means they will need to go up the risk ladder by offering personal and other types of loans. Most Robinhood users are young and not as affluent as the older demographics of some other broker-dealers. Accordingly, debt consolidation could be something they would like to get into as well.

My guess is that Robinhood will also try to open a credit card in the future as well to deepen themselves in consumer banking, integrate it within the app, and give them some type of incentive to sign up (e.g., X percent cash back).

There will also be a push to offer more competitive products and services. Zero commissions as a perk will become less marketed as it becomes more generic and not as much of a competitive advantage.

Brokers will increasingly push into advisory services. This can include cheaper, passive options, such as “robo advisors”, which put you into investment products based on your preferences (e.g., conservative, moderate, aggressive), and charge some type of fee, usually based on the volume of assets invested. It will also include human-based services for those that have investment advisory businesses. It can be trader education (e.g., articles, webinars), trade analysis tools, or even the possibility of trading firm capital with web- or platform-based “trader challenges” if they can prove their ability through simulated trading environments. (Such trading competitions can also serve as brand awareness campaigns, to get prospective clients familiar with and hooked on their trading technology.)

So, the line between pure play brokerages and consumer banks will become more blurred. Value additive products and services and effective lending will become key.

Brokers will increasingly become integrated cash management shops (checking, savings, brokerage, IRAs, money market, CDs) rather than trying to singly focus on one product they might have a specialty in.

Naturally, this will lead to some consolidation in the industry. Not all brokers will be able to survive the loss in commissions revenue and will need to combine skill sets with other firms (through M&A activity or partnerships) to achieve more diversified revenue streams. A broker-dealer like Schwab is less dependent on commissions revenue than a broker like TD Ameritrade. Some smaller brokers have competed on offering inexpensive trades ($1-$3). That was formerly cheap relative to the $5-$10 per-trade fees that were popular until very recently. Those firms will struggle the most.

Fallout in other parts of the industry

Brokers aren’t the only ones affected. Other companies offering “orphan” products will feel the pressure as well.

Marcus (from Goldman Sachs) is having issues from the opposite side. They have a savings account product, but lack a retail brokerage operation and other products that are important to compete well in consumer banking.

Marcus’s savings yield is decent, but is only in line with a dozen or more other products. And front-end USD rates are likely to come down 75-100bps over the next year so the ~2 percent yield isn’t sustainable anyway. They don’t have a mobile app. They don’t offer checking accounts – generally, those who have a savings account would prefer, if possible, to have it in the same place as their checking. They don’t offer brokerage accounts or IRAs. And, of course, they don’t have brick-and-mortar branches to get walk-ins from off the street.

Their competitors are building or have built out the full set:

– Fidelity: checking, savings, brokerage, money market, CDs

– Charles Schwab – same

– Merrill Lynch – same

– Capital One – same

– Robinhood – getting there

Goldman Sachs has lost about $1.3 billion building it out. While building anything out takes time and expense, Marcus was supposed to provide a stable positive source of revenue to help compensate for riskier parts of the business, such as trading.

And for Goldman, getting the deposits isn’t the hard part. It’s their consumer lending that’s been an issue, where they aren’t as experienced. Bad debt write-offs are higher than their bank and non-bank competitors. That means if consumer lending is something they want to do more of moving forward, they need more experience in this area. That likely entails the need to pluck off people in the industry experienced in consumer loan underwriting (e.g., subprime lending companies, credit cards).

Consumer lending could also not be the best choice for a firm like Goldman, which has showed up late. One of Goldman’s best assets is their brand. This means they don’t necessarily have to compete for low- to average-income customers and enter a fairly saturated consumer loan space. The brand more logically caters toward using the Marcus savings account product as an onboarding platform into wealth management – people in the estimated $1mm to $10mm range that could be integrated as customers down the line. Lending could be oriented more toward private wealth management or for brokerage clients.

The Marcus name could also be extraneous (as opposed to just being “Goldman Sachs”). Banks and financial institutions trying to rebrand is costly and difficult.

Conclusion

Brokers will still collect some commissions on many trading instruments – e.g., options, futures, fixed income, mutual funds, non-domestic securities – and will still make money off order flow and margin lending. But losing the bulk of commissions revenue is still a material bite into most brokers’ financial health.

This will drive a charge into advisory services and cause more brokers to chase net interest income. Advisory services will include educational content as a “free” perk. Value added services will include “robo advisors” with varying degrees of “passive robo” and “active robo” management. Human-based advisory services will be part of it. Additional products will include trade analysis, trade ideas / trade generation, risk management, and related tools.

They will also attract more customers through value-added savings and savings-like accounts. Such tactics will include partnering with various banks to increase account insurance relative to standard accounts.

Moreover, brokers will need to increase what they earn on interest income to compensate. As interest rates go down (the US will follow other developed markets down to zero), this pushes all investors and traders into riskier assets, holding all else equal.

Brokers are no different and will have to take more credit and/or duration risk. This could mean personal lending, auto lending, mortgages, debt consolidation, and even credit cards. For most, this will be difficult, as consumer lending requires a different type of professional skill set.

Some brokers won’t be able to compete and may need to sell themselves. Accordingly, I think we can expect consolidation and more M&A activity in the brokerage and consumer banking industry going forward. Consumer banking will continue to become more competitive and see margin compression as more entrants vie for a piece of the pie. At the same time, with brokerages becoming ensconced in businesses laced with credit risk, this also makes them more cyclical and riskier as companies to invest in.