I’ve Been Trading for 60,000+ Hours: What I’ve Learned

After over 60,000 hours in the markets, this is what I’ve learned.

These reflections are just my own perspective. There are many viable ways of doing things. They’re not definitive answers, but observations you may find useful as you develop/refine your own approach.

Take what resonates, question what doesn’t, and remember that the ultimate test of any concept or principle is how it holds up in your own practice and experience.

Key Takeaways – I’ve Been Trading for 60,000+ Hours: What I’ve Learned

- Diversify

- What you know is low relative to what you don’t know

- All known information is in the price

- Think in probabilities

- There is no sure thing

- Have uncorrelated returns streams

- Correlations are fluid, especially in the tails of distributions

- Backtest and stress-test

- Avoid overfitting: past data isn’t the future

- Systemize your decision-making rules – are they repeatable and scalable?

- What is your “neutral” position?

- Markets are a “low-validity” domain

- Define your downside and have a capital cushion

- What are your non-negotiables?

- Don’t view leverage as a black-and-white thing (but use judiciously)

- Think of how to produce other forms of leverage

- Think through the various forms of risk

- Consider opportunity cost

- Don’t overemphasize one method of analysis

- Think through who’s buying, selling, their sizes, and motivations/incentives

- Market edges don’t last

- Know the difference between noise and signal

- Look at things in terms of expected value

- It’s not about predicting the future (de-emphasize forecasts)

- For institutional capital, how can you be unique?

Diversify

Diversification is the cornerstone of long-term survival in markets.

No matter how much conviction you have in an asset, an industry, asset class, or even an entire economy, the world changes in ways that can’t be predicted.

What looks safe and unstoppable today can become risky, stagnant, or simply not what it was.

Spreading exposure across different areas avoids being overexposed to a single point of failure.

Diversify Among Assets

A portfolio concentrated in one asset, whether it’s a single stock, a bond, or even a commodity, is fragile.

Individual assets are exposed to risks specific to their sector, management, or structural vulnerabilities.

Diversifying among multiple holdings reduces the impact of any one poor outcome.

Diversify Across Asset Classes

Stocks, bonds, commodities, and customized strategies respond differently to growth, inflation, and interest rate changes at the macro level.

(Related: The 4 Main Drivers of Asset Returns)

Holding exposure to more than one provides better balance.

When equities sell off when growth and inflation/rates come in above expectation, government bonds or gold may act differently.

Combining asset classes in a well-balanced way can build a portfolio that can weather multiple economic and market environments.

Diversify Across Countries

Economic growth and policy are not synchronized worldwide.

One country can face debt crises or recessions while another grows rapidly.

Diversifying geographically prevents you from being tied entirely to the political, monetary, or economic fate of a single nation.

Diversify Across Currencies

Currencies fluctuate based on interest rates, trade balances, and capital flows.

Being tied exclusively to one currency exposes you to devaluation or inflation.

We pay a lot of attention to the nominal value of our assets, but not enough attention to the value of the currency as it seems like a relatively static thing.

Holding assets in multiple currencies provides protection against domestic monetary mismanagement and improves resilience.

Don’t Be Dependent on One Thing

The central idea of diversification isn’t chasing outperformance and looking for the one or a few big things, but surviving the inevitable shifts.

Leaders rotate. Trends reverse. The once-dominant becomes ordinary.

You won’t get the big ups like concentration will, but it will help avoid the big downs.

What You Know Is Low Relative to What You Don’t Know

One of the easiest mistakes in trading and investing is overestimating how much you know.

Markets are vast, complex, and influenced by countless variables that are beyond any individual’s grasp – e.g., politics, central bank actions, technological breakthroughs, geopolitical shocks, and human (and machine) behavior at scale.

Professionals with decades of experience – even though they have more information, better analysis, and better technology – operate with incomplete information. They just know how to deal with it better.

Novices in markets are often very sure of themselves because they don’t have the metacognition to recognize their own skill, knowledge, and experience gaps.

Pretending to have certainty, due to a lack of it, is falsely comforting and not the right way to go.

Humility is therefore a core skill.

Approaching markets as if you hold the key insight that everyone else has missed usually leads to disappointment or really messing things up.

Recognizing that your knowledge is small relative to the unknown – and relative to what’s already discounted in the price – keeps you cautious and disciplined.

Novices often fall into the trap of believing their conviction when it’s unwarranted. They forget that for every position taken, there is someone on the other side of the trade, often an institutional investor with deeper resources and broader access to information.

The market price reflects a collective synthesis of available knowledge.

To think you consistently know better requires an extraordinary edge, which is something that’s typically rare and fleeting.

Admitting the limits of what you know prevents overconfidence, which is the seed of many financial disasters.

Practicing Humility in Decision-Making

Humility doesn’t mean avoiding conviction or failing to act.

You still need the courage to follow through on the decisions you want to make.

It means framing decisions probabilistically, building in margins of safety, and always considering the possibility of being wrong.

A humble investor asks: What am I missing? Who knows more than I do? What happens if I’m wrong?

By structuring positions with these questions in mind, you avoid betting more than you can afford on uncertain outcomes.

The reality is that the unknown will always be larger than the known.

Accepting this truth changes how you manage risk and approach strategy.

It keeps you from doubling down recklessly, and it reminds you to respect the market’s ability to surprise.

All Known Information Is in the Price

Markets are forward-looking discounting mechanisms.

Every price reflects the collective judgment of millions of participants, each weighing current data, expectations, and risks.

When you buy or sell, you’re competing with the collective synthesis of what’s already known.

This means that the key to generating returns isn’t identifying whether news is good or bad, but whether it’s better or worse than what was already priced in.

For example, a company might report record profits, but if the market expected even higher results, the stock can still fall.

Similarly, gloomy economic headlines don’t always mean markets will decline if traders/investors had already prepared for bad news.

The relationship between expectations and new expectations/reality is what drives price movement.

Understanding this principle prevents the mistake of assuming that “obvious facts” create easy trades.

What matters is the gap between consensus expectations and future outcomes. Price action is the constant adjustment process as new information closes or widens that gap.

| Scenario | Market Expectation | Actual Outcome | Price Reaction |

| Earnings beat | Weak results expected | Results slightly better | Stock rises |

| Earnings miss | High growth expected | Results disappoint | Stock falls |

| Bad news | Severe downturn priced in | Downturn mild | Market rallies |

Think in Probabilities

Markets Are Uncertain by Nature

Every trade you make is a bet on an uncertain future. Outcomes aren’t fixed; they fall within a range of possibilities.

While investors and market commentators often talk in absolutes (“this stock will rise,” “the dollar will fall”), the reality is that nothing in markets is guaranteed.

You’re never dealing with certainties but with probability distributions.

And another challenge is that these distributions can’t be known with precision, as they shift with new information and unexpected events.

It’s the Probabilities That Matter

What matters is not whether something is possible, but how likely it is compared to other outcomes.

A rare event might happen, but if its probability is low and its cost to hedge is high, allocating heavily toward it can be inefficient – unless it’s not negotiable that you need to hedge against a certain outcome.

Conversely, if an event has a modest probability but extreme consequences, ignoring it can be dangerous.

Thinking in probabilities helps you balance expected returns with potential risks rather than chasing the illusion of certainty.

And even the probabilities can’t be precisely known.

Framing Decisions Probabilistically

Good decision-making means framing every choice as: What is the range of outcomes, and what probability do I assign to each?

You don’t need exact numbers, but you must think in relative terms; what’s more likely versus less likely. This mindset helps size positions, define risk, and avoid catastrophic mistakes.

By constantly asking, “What is the likelihood I’m wrong?” you shift from prediction to risk management.

In the end, you succeed not by being right all the time, but by managing probabilities well enough to win over the long run.

There Is No Sure Thing

In markets, there are no guarantees. No matter how strong your research, how compelling the story, or how confident you feel, every position carries unknowns.

This principle ties directly to diversification and probabilistic thinking: if the future can’t be predicted with certainty, you must spread your bets and manage risk as if you will sometimes be wrong.

Many traders/investors fall into the trap of believing that one trade, one asset class, or one strategy will always deliver. But that’s not the case and keeping this in mind helps to avoid overconcentration and reckless leverage.

The best you can do is assign probabilities, diversify exposures, and make sure that it’s not all on a single or limited number of outcomes.

Have Uncorrelated Returns Streams

Why Uncorrelated Streams Matter

Having uncorrelated return streams is one of the best ways to build a durable portfolio. If all your investments respond to the same forces, diversification is an illusion.

For example, stocks and corporate bonds both depend heavily on growth and credit conditions, so in a crisis they often fall together. Even if they’re indexes.

Adding assets like Treasuries (nominal and inflation-linked) or gold, which respond differently to interest rates and inflation, creates better diversification.

Those with strong derivatives backgrounds can go beyond this, but it requires knowing what you’re doing. Unique asset classes (e.g., reinsurance) is another.

Process-oriented returns streams are another avenue for diversification. And they can sometimes be easier, but can also sometimes be difficult to scale past a point.

The goal is to combine exposures that react differently across economic environments so your total portfolio remains more stable.

Expanding Beyond Traditional Assets

As mentioned, institutions often go further by looking for returns from custom options strategies, catastrophe reinsurance, or process-oriented strategies that can be scaled.

These approaches aim to generate returns independent of equity or bond cycles – or credit cycles in general.

However, not all diversification is equally useful. Illiquid assets such as private equity, real estate funds, or niche credit strategies may appear uncorrelated, but much of that comes from infrequent pricing rather than true independence.

Illiquidity can mask risk until stress forces revaluation.

The key is balance: mix traditional markets with scalable, process-driven streams, but don’t rely too heavily on illiquid “diversifiers.”

The goal is resilience, not a false sense of safety.

| Return Stream Type | Typical Drivers | Diversification Value | Key Risks |

| Stocks | Growth, earnings, sentiment | Strong long-term returns | Cyclical, vulnerable in recessions |

| Bonds (Gov’t Treasuries) | Interest rates, monetary policy | Often hedge equity drawdowns, and we think adding inflation-linked securities can be a great idea too | Inflation erodes value, correlation can shift, fixed upside if held to maturity, default risk (even if low for most governments) |

| Gold | Inflation (long-run, not short-run), currency weakness, safe-haven demand | Hedge against monetary instability | No yield, higher real rates reduce appeal |

| Custom Options Strategies | Volatility surfaces, risk premia, market-neutral strategies, covered calls/puts, various customizations | Can produce asymmetric, uncorrelated payoffs | Complex, takes expertise, model risk, margin exposure |

| Catastrophe Reinsurance | Natural disasters, actuarial risk | Returns independent of markets | Event concentration, illiquidity |

| Process-Oriented Strategies | Rules-based trading, statistical arbitrage, your own projects | Can be faster to create your own assets, scalable and repeatable edge | Model decay, crowding, execution costs |

| Illiquid Assets (PE, RE, Private Credit) | Business cycles, financing conditions | Appear uncorrelated due to infrequent pricing | Liquidity traps, hidden correlation in crises |

Correlations Are Fluid, Especially in the Tails of Distributions

Correlations Aren’t Static

Correlations between assets are often treated as fixed, but in reality they change with the macro environment.

The classic stock–bond diversification benefit, for example, depends on what’s driving the economy.

When growth shocks dominate, equities fall while government bonds rally, providing a hedge. But when inflation shocks dominate, both stocks and bonds can decline together. 2022 was an example.

Correlations, therefore, are conditional on the forces shaping markets at a given time.

Behavior in the Tails

Correlations also behave differently during extreme events – namely, the “tails” of the distribution.

In crises, liquidity becomes the primary concern.

Traders/investors of all sizes rush to sell what they can, not just what they want to.

This forced selling compresses correlations across assets, making things that once appeared uncorrelated move together.

Commodities, equities, bonds, and even some alternatives can all decline simultaneously when liquidity is scarce.

Implications for Risk Management

The fluid nature of correlations means that backtests built on average relationships can be misleading.

What looks like a well-diversified portfolio in normal times may not do great when stress hits.

Effective risk management requires stress-testing under multiple regimes and recognizing that diversification often weakens when you need it most.

The lesson is not to abandon diversification, but to respect its limits.

True resilience comes from combining assets and strategies with different economic drivers while preparing for the reality that, in the tails – particularly the left tail – correlations often converge.

Backtest and Stress-Test

Simulation exposes weak thinking safely and shortens the learning curve.

You can run a zillion scenarios and learn from them without incurring real-world cost.

Backtesting

When applying a strategy to historical data, you can see how it would have performed in past conditions and economic/market environments and uncover weaknesses that might not be obvious at first glance.

For shorter-term, rules-based strategies, backtesting can be especially valuable.

Patterns repeat more often at smaller time scales, and well-structured tests can help reveal whether a trading edge is strong or just random noise. (Related: How Does Skill Take to Be Visible?)

But backtesting has limits.

The further out your horizon, the more the world changes.

Long-term strategies have to grapple with structural shifts in policy, regulation, technology, and market behavior.

Different products, instruments, and market players become more prominent.

A strategy that looks good across 40 years of data may fail going forward because the drivers of return have evolved.

This is why relying solely on backtests can be misleading.

The data can only reflect what has already happened, not what could happen.

Still, it’s important information.

Stress Testing

That’s where stress testing becomes essential.

Stress testing imagines conditions beyond the historical record: a sudden spike in inflation or unemployment, a collapse in liquidity, or a geopolitical shock.

Many of the most damaging events in market history, from the 2008 financial crisis to the pandemic of 2020, had no close parallel in the backtest data.

Yet they reshaped portfolios dramatically.

By asking, “What if something unprecedented occurs?” and running your strategy through synthetic scenarios, you expand the range of risks you’re prepared for.

In practice, strong strategies use both: backtesting to refine rules and measure historical performance, and stress testing to guard against the unknown.

Markets will always deliver surprises. Preparing for what hasn’t happened is just as important as studying what has.

Related: Portfolio Simulations

Avoid Overfitting: Past Data Isn’t the Future

Backtesting is useful, but it tempts traders to refine strategies until they look perfect on historical data.

This is the danger of overfitting – i.e., designing a model that captures noise rather than signal.

A strategy that “works” brilliantly on the past may be perform quite poorly when faced with new data, because markets never repeat in exactly the same way.

The future will always contain events, correlations, and shocks that history didn’t capture.

Avoiding overfitting means valuing simplicity, using out-of-sample testing (i.e., testing on new data), and remembering that doing well across various environments matters more than perfection.

The goal isn’t to find the best backtest and optimizing off that, but a durable process that adapts across regimes.

| Overfitting Problem | Description | Real-World Risk |

| Too Many Parameters | Excessive tuning to past data | Fails on new data |

| Curve Fitting | Tailoring rules to rare past events | No predictive power |

| Data Snooping | Testing endless variations until one “works” | False confidence |

| Lack of Out-of-Sample Testing | Never tested outside training set | Hidden fragility |

Systemize Your Decision-Making Rules – Are They Repeatable and Scalable?

From Ideas/Opinions to Tested Rules

Every trader has opinions: on markets, on prices, on direction. But opinions alone aren’t enough.

Acting immediately on every thought is a recipe for inconsistency… or worse.

Instead, treat ideas as hypotheses. Don’t trade them right away.

First, backtest them to see how they perform historically, then stress-test them against extreme scenarios that may never have occurred.

This process filters out weak or biased ideas before real capital is put at risk.

Even discretionary traders – i.e., traders who run their strategies manually – benefit from codifying their decision-making.

Writing down rules helps identify when an approach is strong versus when it’s just a hunch.

The Importance of Repeatability and Scalability

Strong strategies are those that can be applied repeatedly, not just once.

Even if trading is not your business long-term, these are important.

Is what you’re doing repeatable? And can it be scalable where the inputs you’re doing now lead to long-term benefits that accrue without continual inputs?

In trading itself, tactical trades may pay off occasionally, but they rarely build long-term success because they can’t be scaled.

Instead, ask yourself: What are my rules? Can they be applied across markets, time periods, and environments?

Repeatability gives better consistency – and a base off which to iterate – while scalability allows your process to grow with larger amounts of capital.

This is why systematic frameworks, even when partially or even fully discretionary, are so valuable.

They take subjective ideas and refine them into repeatable, rule-based processes that can survive or be improved over time.

The aim is ultimately discipline – knowing that every decision is based on a foundation of tested, scalable logic rather than fleeting instincts or random opinions.

And, if you can, have a bias toward reversible decisions.

Related: The Importance of Structure and Repeatability

What Is Your “Neutral” Position?

Every trader and investor should ask: If I knew nothing about the world, what would my portfolio look like?

This thought experiment points to your neutral position – namely, the baseline mix designed to perform reasonably across all environments.

The goal is not to maximize returns in one scenario but to balance exposures so that no single outcome – or a handful of correlated (or potentially correlated) outcomes – can produce unacceptable outcomes.

Neutrality accepts that forecasting is unreliable and instead emphasizes resilience.

Different assets shine under different conditions.

- Stocks tend to perform best when growth is stronger than expected and inflation remains low to moderate, conditions that support earnings and valuations.

- Government bonds, in contrast, excel during periods of weak growth or outright deflation, when interest rates fall and capital seeks safety.

- Commodities often rally during inflationary periods or when supply shocks push prices higher, sometimes becoming the very cause of inflationary pressure.

- Cash holds value when money and credit are tight, providing both safety and optionality when other assets are stressed.

- Gold operates as a kind of inverse currency; its intrinsic value doesn’t change (gold is always gold), but it strengthens when fiat currencies weaken or when confidence in monetary systems erodes.

A neutral portfolio incorporates elements of all these assets, accepting that no one knows the future.

The goal isn’t necessarily constant outperformance but balance, so that whatever emerges (growth, recession, inflation, stagflation, or deflation) you have something in place that can either benefit or at least cushion the blow.

A well-constructed neutral position is the foundation that allows deliberate, active decisions rather than desperate reactions when the environment or ongoing paradigm changes.

Markets Are a “Low-Validity” Domain

Markets are classic low-validity domains.

This means that outcomes are noisy, feedback is delayed, and signals can be misleading.

A profitable trade may come from sheer luck, while a well-reasoned position might lose because of events no one could foresee.

Novices tend to be very sure of things because of classic mistakes – e.g., that obvious facts make for obvious trades without understanding that what’s known is already in the price.

So, if they happen to be right, “they knew it” (or it’s just hindsight bias); if they’re wrong, they either forget about their guess, they were unlucky, or the fault lies with something or somebody else.

This disconnect makes it hard to separate skill from randomness.

Over time, even disciplined traders can mistake luck for skill/knowledge, while genuine skill can appear invisible when masked by short-term noise.

In such environments, intuition becomes unreliable. What feels like pattern recognition may just be the brain misreading randomness.

Distorted Learning and Hidden Incompetence

Because feedback is inconsistent, it often distorts rather than clarifies.

Making a good decision with a bad outcome, or a bad decision with a good outcome, trains the mind to trust unreliable cues. Even seasoned professionals can be fooled.

Worse, as mentioned earlier, people with little skill in markets often lack the metacognitive skill to realize their own incompetence. There’s simply no foundation from which to know what’s not understood.

They’re not just unskilled; they don’t know that they don’t know and don’t have any process for getting the feedback to actually learn and improve. (Related: Dunning-Kruger Effect in Trading)

There’s no feedback loop strong enough to correct them.

That is why humility and rigorous process matter so much in market environments.

Define Your Downside and Have a Capital Cushion

Guarding Against the Unacceptable

Diversification reduces exposure to single points of failure, but it can’t totally eliminate the possibility of damaging losses.

Even if backtesting shows a maximum drawdown of X% over decades, it can still go beyond that in the future.

Every trader/investor must decide in advance what outcomes are unacceptable.

These might include losing a set percentage of capital, being forced to liquidate, or facing a drawdown that destroys confidence.

In real life, people buy insurance to avoid financial problems from rare events.

Many portfolios can benefit the same protection.

Out-of-the-money options, for example, function like insurance. They may carry a steady cost, but they can protect against risks that would otherwise cause irreparable damage.

But like anything, it’s nuanced. Some portfolios may not need defined hedges and the cost may be too much of a drag on long-run returns.

The Importance of a Cushion

Even with diversification and hedges, portfolios face volatility.

A sufficient capital cushion helps so you won’t be forced to sell at precisely the wrong moment – i.e., when assets are most undervalued and liquidity is scarce.

Without that buffer, you risk margin calls or liquidity squeezes that compel you to exit just before recovery.

Ask yourself: If my portfolio suffers a severe drawdown, can I hold steady, or will I be pushed out? If survival depends on good conditions (or certain conditions, in general), you’re taking too much risk.

Balancing Growth and Survival

Defining your downside is about balancing growth with longevity.

Compounding only works if you stay in the game.

A portfolio positioned for high upside but with no protection against catastrophic loss is fragile.

Combining diversification, prudent hedging, and a deliberate capital cushion, you create a stronger portfolio that you never have to worry about.

Drawdowns are inevitable, but those drawdowns should never consume enough capital that they throw you off course (or worse).

Defense is the foundation, and defining your downside is how you build it.

Like anyone growing up playing a sport, you first like to express yourself playing offense – scoring goals, making baskets, etc. – but eventually you learn the importance of defense and having a more balanced approach for best results.

Define the Non-Negotiables

Probably the most obvious example in trading is drawdowns or tail risk.

What can’t happen? What simply isn’t acceptable?

Like most traders, when I began I liked “playing offense” and whatever gains I had didn’t last.

So, I learned to do things differently.

As covered here, I learned about things like diversifying, having uncorrelated return streams, balancing risk so parts aren’t dominating. I also learned about hedging and cutting off risk completely with things like out-of-the-money options.

But it also extends beyond that because risk in trading goes beyond basic P&L. It shows up as a chain reaction. A drawdown can become a margin call. A margin call becomes forced liquidation. Forced liquidation becomes selling at the worst possible time.

And once you get pushed out, it doesn’t matter that you were “right later.” The damage is already done.

So the point of defining non-negotiables is to protect your ability to stay in the game when the environment turns hostile.

Preferences vs. Constraints

It’s good to separate preferences from constraints.

- Preferences are things you’d like to avoid.

- Constraints are outcomes that would break your system, your psychology, or your capital base.

A few examples of real non-negotiables:

You can’t allow a single position, theme, or factor exposure to dominate the portfolio’s fate. That includes hidden dominance, like five “different” positions that all crash together under certain circumstances.

If your edge depends on never missing a hedge roll, never getting slipped, never having a tech outage, it’s a fragile story.

You can’t accept a loss profile where the left tail is unbounded while the right tail is capped. If you’re repeatedly selling convexity without owning any, you’re collecting small premiums while borrowing catastrophe risk.

You can’t rely on correlation assumptions as if they’re laws of physics. Correlations are behaviors, and behaviors change under stress. Your non-negotiable is that your portfolio remains survivable even when correlations converge.

And you can’t build a portfolio that only works in one macro regime, one volatility regime, or one liquidity regime. A strategy that needs “normal” conditions is a bet on normality.

Once you’ve stated the non-negotiables, you translate them into concrete rules. The rules need to be specific enough that you can follow them on your worst day.

For example, if a drawdown beyond 20% isn’t acceptable, that’s where you think about owning options so losses can’t fall beyond that.

It’s important to not treat “risk management” as something you do after you find a trade. The non-negotiables come first, because they define which trades you’re allowed to take in the first place.

If you define them correctly, they act like an internal constitution. They limit your freedom in the short run so you can keep your freedom in the long run. They stop you from waking up one day realizing you built something that only works when nothing goes wrong.

Institutions have them. Many traders/investors find them draconian, but they’re there for a reason.

Psychological Non-Negotiables

And the final piece is psychological, not mechanical. Your non-negotiables must protect you from your own predictable failure modes.

If you see a 30% drawdown in a 50-year simulation, that might not seem bad if the results were ultimately good. But it’s different than living through it.

If you know you tilt after a losing streak, then your rules should automatically reduce risk after a drawdown. If you know you get overconfident after a winning streak, then your rules should cap risk and force rebalancing when things go well.

The market will always find the weakest link in your process. Defining the non-negotiables is how you make sure the weakest link isn’t something that can end your career.

Don’t View Leverage as a Black-and-White Thing (But Use Judiciously)

When Leverage Should Be Avoided

For beginners or those managing simple retirement portfolios, leverage is usually best left untouched.

Adding borrowed exposure without deep understanding magnifies volatility and the risk of ruin.

A novice using leverage often underestimates how quickly things go south. These types of portfolios effectively have narrow operating windows that don’t last.

And without risk management, they may be forced into permanent losses that wipe out progress.

In this context, the conservative stance of avoiding leverage altogether makes sense.

Leverage as a Means of Capital Efficiency

For experienced traders and investors, however, leverage is not inherently reckless. It’s a matter of capital efficiency.

A concentrated, unleveraged portfolio in one asset class can be far riskier than a balanced, diversified portfolio that uses modest leverage.

For example, allocating across stocks, bonds, and commodities while applying moderate leverage can create smoother returns (and better in a risk-adjusted sense) than relying solely on equities.

In this sense, leverage enables diversification across inherently different streams without sacrificing overall return.

Used carefully, it can reduce portfolio fragility rather than increase it.

The Key Is Judicious Use

Leverage is neither good nor bad; it depends on how it’s applied.

Judicious leverage requires clear rules about maximum drawdowns, capital cushions, and an understanding of liquidity needs in stress scenarios.

It should never be used to chase short-term gains but rather to construct portfolios that balance growth with stability.

The critical question is not “should leverage ever be used?” but “under what circumstances, and with what safeguards?”

When managed with discipline, leverage can help build a strong, efficient portfolio.

When used carelessly, it’s one of the fastest paths to disaster.

Think of How to Produce Other Forms of Leverage

Time Leverage

Time can be used with varying levels of efficiency. Many traders waste energy on low-value tasks or chasing noise.

True time leverage comes from focusing on the highest-impact activities (researching strategies, refining processes, or building systems) rather than reacting to every tick.

Using time well multiplies effectiveness without adding risk.

Think in terms of return on time, as you only have so much time and energy.

And it can be especially important when your financial resources are limited.

Return on time is a key variable. At the same time, always weigh the benefit of gathering more information and being well-informed versus the cost of not deciding.

Capital Leverage

Allocating capital across uncorrelated streams, or using derivatives for efficient exposure (if you have that expertise), allows you to get more balance and return per unit of risk while reducing left-tail risks.

Smart capital leverage is about efficiency, not speculation.

Automation Leverage

Repetitive tasks consume attention.

Automating trade execution, reporting, or risk checks frees you to concentrate on judgment and strategy.

Systems never tire. If you can build them, it’s great to make automation a form of compounding efficiency.

There are lots of different forms of software and tools these days.

People Leverage

Hiring or collaborating expands capacity.

A single investor is limited in what they can analyze and execute.

Leveraging the skills of others, whether through teams or partnerships, you scale far beyond your own bandwidth.

Intellectual Leverage

Try to not do everything in your head. Our lives are complicated enough as they are.

Offloading can reduce your stress and help you scale.

Documenting insights, building frameworks, and turning lessons into repeatable rules creates lasting leverage.

Instead of relearning the same lesson, you build a system that remembers for you, allowing knowledge to compound.

Consider a “second brain” you can dump everything into.

We wrote about other productivity and time management systems for traders here.

Think Through the Various Forms of Risk

Volatility Risk

Volatility is the most visible form of risk, but it isn’t always bad.

It creates drawdowns that can shake confidence, yet it also creates gains as well as opportunity for rebalancing and compounding if managed correctly.

Liquidity Risk

Markets don’t always let you exit at the price you want.

In times of stress, bid-ask spreads widen, depth vanishes, and forced selling magnifies losses.

Liquidity risk is often invisible until it matters most.

If you’re buying illiquid assets – which can be part of a prudent diversificatio approach – be sure you’re getting enough return to justify the lack of liquidity.

Credit Risk

When lending or owning debt, there’s always the chance the borrower won’t pay.

Credit risk can surface slowly, through deteriorating fundamentals, or suddenly, through default.

It’s the hidden heartbeat of fixed-income markets.

Inflation Risk

Positive nominal returns can be destroyed if inflation erodes real value.

Protecting against this requires assets like commodities, inflation-linked bonds, or assets that can help keep pace with rising prices.

Deflation Risk

Less discussed but equally dangerous, deflation erodes profits, wages, and debt sustainability.

Bonds may thrive, but equities and leveraged assets struggle.

Japan’s lost decades are a reminder of how persistent deflation can be.

Correlation Risk

As mentioned above, assets that look uncorrelated in normal times often converge in crises.

This is why portfolios can fail when diversification is most needed. Stress-testing is the only way to prepare.

Operational Risk

Systems fail, processes break, and errors multiply.

A single execution error, faulty model, or data glitch can be really bad.

Have strong controls and redundancies.

If your broker is having system issues, do you have a backup (if only to hedge)?

Outside of trading, if you’re a business owner and reliant on certain platforms to sell your products and services, they could very well own the entire customer relationship and pull the plug on you for any reason.

Behavioral Risk

Perhaps the most underestimated form of risk: yourself.

Overconfidence, fear, and greed can ruin a good strategy on paper.

Recognizing your own biases is as critical as analyzing the market.

Consider Opportunity Cost

Every capital allocation decision has two sides: what you choose to do, and what you give up by not choosing something else.

Opportunity cost is the price of allocating capital, time, or attention to one idea instead of another. Too often traders/investors focus only on the returns of the positions they hold, without asking whether those positions are the best use of resources compared to the alternatives available.

Holding cash might feel safe, but the opportunity cost is missing out on higher returns (and factor in inflation and taxes).

Conversely, staying invested in a mediocre strategy can prevent you from looking at higher-quality opportunities.

The same applies to time. Hours spent watching every market tick could be better used building or refining systems or learning new methods.

Thinking explicitly about opportunity cost forces discipline.

It reminds you that doing nothing, or sticking with the familiar, carries a cost just as real as any realized loss.

Don’t Overemphasize One Method of Analysis

Markets are ecosystems made up of countless participants (hedge funds, central banks, corporations, retail traders, insurers, pension funds) each with different goals and time horizons.

Some seek short-term profits, others long-term stability, and still others try to hedge risks or manage liabilities.

These diverse motivations generate the flows of money and credit that shape prices and drive volatility.

Relying too heavily on one method of analysis, whether it’s technicals, fundamentals, or macroeconomic signals, risks missing the bigger picture.

Technical traders may understand how to measure short-term momentum but ignore the impact of central bank policy.

Fundamental analysts may build detailed models yet underestimate liquidity shifts.

Macro thinkers may see broad forces but miss micro-level drivers that move prices day to day.

The lesson is to broaden your perspective. Use multiple lenses to evaluate the same market.

When different methods align, conviction strengthens. When they diverge, you become less certain.

Overemphasizing one form of analysis blinds you to the complexity of markets.

Balance keeps you adaptive.

| Participant Type | Primary Goals | Impact on Markets |

| Hedge Funds | Generate alpha, manage risk, exploit inefficiencies | Add liquidity, increase volatility around events |

| Central Banks | Control inflation, stabilize currency, support employment | Influence interest rates, credit flows, and asset prices |

| Corporations | Raise capital, hedge costs, manage cash flows, Treasury functions, make strategic investments | Issue debt/equity, engage in buybacks, drive sector trends |

| Retail Traders | Seek personal profit, speculation, or long-term savings | Can create short-term swings, amplify sentiment trends |

| Pension Funds | Preserve and grow capital for liabilities | Provide steady, long-term demand for bonds and equities |

| Insurers | Match assets to liabilities, protect against tail risks | Allocate into bonds, reinsurance, or alternatives |

| Sovereign Wealth Funds | Diversify national reserves, seek stable growth | Large flows across global asset classes, long horizon |

| Banks & Dealers | Provide liquidity, manage balance sheets, earn spreads | Influence short-term funding markets and credit flows |

Think Through Who’s Buying, Selling, Their Sizes, and Motivations

Markets Are Driven by Flows

Prices in markets are not determined by abstract theories alone but by the interaction of buyers and sellers – who they are, how much capital they control, and what their incentives are.

Governments, for instance, issue bonds to fund deficits. The demand for those bonds comes from a wide spectrum of players, each with unique motivations.

Domestic buyers may care most about real returns relative to inflation, while foreign buyers must factor in currency fluctuations alongside yield.

These competing priorities create the flows that move markets day to day.

Agent-Based Thinking

A useful way to frame this is through agent-based modeling: the idea that markets are ecosystems of different “agents,” each with their own goals, constraints, and decision-making rules.

Pension funds may prioritize liability matching, hedge funds may chase relative-value trades, and central banks may intervene for policy reasons.

None of these agents operate in isolation. Their actions overlap and collide, producing price dynamics that can’t be understood by looking at one perspective alone.

See: Agent-Based Modeling

Limits of Narrow Lenses

We touched on this a bit earlier, but focusing too narrowly on a single method, such as value investing or technical analysis, risks missing the larger drivers of price movement.

While some traders/investors use those methods and they have some influence on prices, they’re still a slim fraction of the overall market.

For example, a stock may appear undervalued by traditional metrics but remain suppressed because large institutions are de-risking or reallocating capital elsewhere.

Similarly, a bond market may not behave according to fundamental growth and inflation expectations if foreign central banks are selling to defend their currencies.

Markets seem “irrational” – and can be irrational based on long-term valuation concerns – only when the true mix of participants and their motivations is ignored.

Understanding Incentives and Size

The size of capital behind each group matters as much as their goals.

A trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund reallocating five percent of its holdings can outweigh the decisions of millions of retail traders.

For example, retail traders tend to be more influential in Chinese markets than US markets, which shows in the greater momentum (e.g., buying what’s “hot”) of the former, as an example.

From studying who is buying, who is selling, and why, traders/investors gain a deeper view of what’s really driving markets.

Recognizing these flows prevents confusion during periods when theory and reality diverge and helps your strategy adapts to the forces actually shaping prices.

Market Edges Don’t Last

Any trading or investing edge that proves consistently profitable will eventually attract attention.

Once others discover and replicate it, the advantage diminishes.

Markets are adaptive systems: participants constantly learn, adjust, and compete.

What works for a time inevitably gets copied, arbitraged away, or overwhelmed by changes.

It works like this in other businesses too.

If many ecommerce shops are selling the same product, other pick up on this and start doing the same thing and competitive edge erodes.

When companies are growing a lot this attracts competitors who want to copy and this can create pressure on margins that are discounted into future stock prices.

This reality makes complacency dangerous. Believing you’ve found a permanent edge is often the first step toward losing it.

The only durable approach is continuous innovation; refining methods, adapting to new information, exploring untapped opportunities. Edges have to evolve as market structure, technology, and regulation evolve.

Even well-established strategies, such as value investing or trend following, experience cycles of effectiveness and drought.

Success lies in recognizing when an edge is fading and being prepared with new approaches.

The market rewards creativity, adaptability, and humility.

Know the Difference Between Noise and Signal

Markets generate a constant stream of price changes, headlines, and opinions.

Most of this is noise. Short-term fluctuations that distract rather than inform.

Noise is especially high on short timeframes. For those focused on capturing the long-term earnings that markets produce, these daily swings can be misleading.

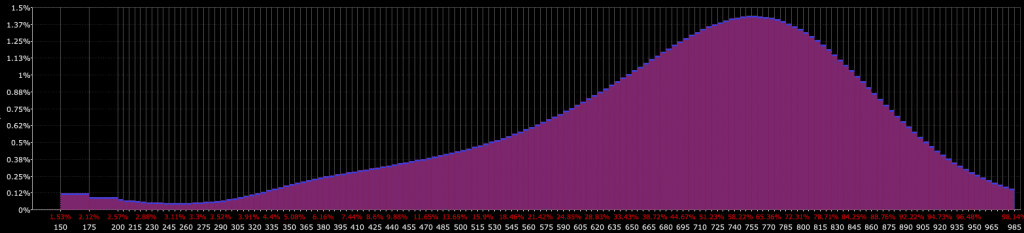

Take the example of a broad stock index. Over time, it may return around 7% per year. Break that down, and it works out to just 0.02% per day when divided evenly across the calendar year. Yet the daily volatility of that same index is often around 1%.

In other words, the signal you’re looking for is tiny compared to the daily noise surrounding it.

The true driver of returns (business growth and earnings) emerges only over years, not days.

Even over one year, only 76% of them have been profitable in the US stock market, looking back over a century.

That’s why certain strategies deliberately stretch their timeframe. By focusing on multi-year horizons, they filter out the randomness of daily movement and home in on the underlying signal.

This doesn’t mean short-term trading can’t work, but it requires a different framework and tolerance for higher noise levels.

It also depends on the nature of the strategy. Capturing earnings is very different than market making.

For most traders/investors, learning to distinguish signal from noise (and aligning strategy with timeframe) is critical to staying disciplined and avoiding costly distractions.

Look at Things In Terms of Expected Value

In trading and investing, decisions should be guided by expected value (EV); that is, the average outcome you’d earn if you repeated the same decision many times.

EV combines both the probability of outcomes and the size of payoffs.

A trade doesn’t have to be “right” most of the time to be profitable.

What matters is that the reward when right outweighs the loss when wrong.

Consider an example:

- 30% chance of being right → gain +$500

- 70% chance of being wrong → lose -$100

The expected value is (0.3 × 500) + (0.7 × -100) = +$80.

Even though the trade loses more often than it wins, the positive EV makes it a smart bet. That is, as long as you can withstand the drawdowns and cover the losses.

This is why disciplined position sizing and risk management matter: they allow you to pursue positive EV opportunities without being forced out before the edge pays off.

And while it’s more comfortable to be right more than you’re wrong, you can still be wrong most of the time if the process is still +EV.

It’s Not About Predicting the Future (De-Emphasize Forecasts)

From the outside, many think that trading and investing is like predicting the future.

But, in reality, it’s not about predicting the future, because forecasts and indicators are often unreliable (again, all information is already in the price) and markets can surprise even the most skilled participants.

What matters more is having a well-structured strategic asset allocation aligned with your goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance.

This foundation creates balance across environments and reduces reliance on guessing outcomes.

Even for shorter-term traders, keeping a strategic allocation in mind is valuable, so that positions fit within a broader, overarching framework rather than depending on short-term forecasts.

The focus should be on spreading your chips out in a balanced and efficient way, not prediction.

For Institutional Capital, How Can You Be Unique?

For traders or managers seeking institutional capital, the key question is: what unique value do you provide?

Institutions, and anybody, can already buy index funds or allocate to broad asset classes at minimal cost.

If your strategy simply mirrors equities, bonds, or commodities, it’s difficult to justify fees or capital allocation.

True value lies in delivering return streams that are not correlated with traditional markets. You can even be better than that – negatively correlated.

This could mean systematic relative-value trades to cancel out market beta, duration-neutrality (stripping out interest rate effects), volatility strategies, niche credit opportunities, or other approaches that diversify institutional portfolios.

Indexing is cheap and efficient, so uniqueness is the differentiator.

| Strategy Type | Correlation to Traditional Assets | Value-Add for Institutions |

| Index Funds | High | Cheap beta exposure |

| Traditional Equity Long/Short | Moderate to high | Limited if beta-driven |

| Systematic Volatility Strategies | Low to moderate | Diversification, convex payoffs |

| Relative-Value Arbitrage | Low | Independent returns, process-driven |

| Niche Credit / Special Situations | Low to moderate | Idiosyncratic alpha |

Conclusion

Markets don’t hand out certainty, only lessons. Many traders and investors discover this the hard way when they mistake conviction for knowledge.

The unknowns are always larger than the knowns relative to what’s priced into markets.

Every trade has someone on the other side with equal conviction and often better resources and a relatively high level of sophistication.

This reality forces you to think probabilistically, protect downside, and diversify among various returns streams that are structured well in a cohesive portfolio.

Focus on a repeatable and scalable process. Structure decisions so the inevitable wrong calls don’t matter all that much.

Markets tend to reward those who prepare for being wrong more than those who insist on being right.