A History of Financial Wipeouts of Wealth in the 20th Century

In this article, we’re going to look at cases of countries in the 20th century where there were full wipeouts, and near-wipeouts, of financial wealth.

This is based on 60/40 portfolios (i.e., 60 percent stocks, 40 percent government bonds) and based on real (inflation-adjusted returns).

A 60/40 stock-bond mix is often taken as a fairly conservative, simple portfolio.

But if you study history you’ll find that this type of portfolio can be extremely risky because:

a) it’s all concentrated in financial assets (i.e., no real, physical assets)

b) it’s all in one country and sometimes countries fall under bad times or are devastated entirely, and

c) it’s all in one currency and currencies rise and fall and don’t last forever

Looking back through financial history, of the national currencies that existed since 1700 (about 750) 80 percent of them no longer exist.

The remaining 20 percent of them have all been significantly devalued at one point or another. This includes even the most credible ones like the US dollar.

Yet changes in currency regimes happen so infrequently that they are rarely considered to be a threat to portfolios (in a similar way to acts of nature).

In this article, we’re looking at only the 20th century. This century saw two World Wars, which bring unique forms of unpredictability and devastation.

The losing countries following WWI were saddled with large war debts. The losing countries following WWII were put under US control (the new top undisputed global power) and received significant financial assistance through the Marshall Plan.

During this time, the losing countries saw their currencies and debts virtually wiped out, which was terrible for those holding them.

We’ll cover full wipeouts of financial wealth in addition to near-wipeouts and other cases where substantial wealth was lost under the 60/40 framework during the 20th century.

Full wipeouts of financial wealth

The following countries had total wipeouts in wealth during the 20th century:

Russia 1918

The Russian Civil War ended with Bolshevik (communist) rule. Debt was repudiated and financial markets were shut down and didn’t return for another 75 years.

Virtually all financial wealth was wiped out. A lot of physical wealth was seized from those who had it during the revolution.

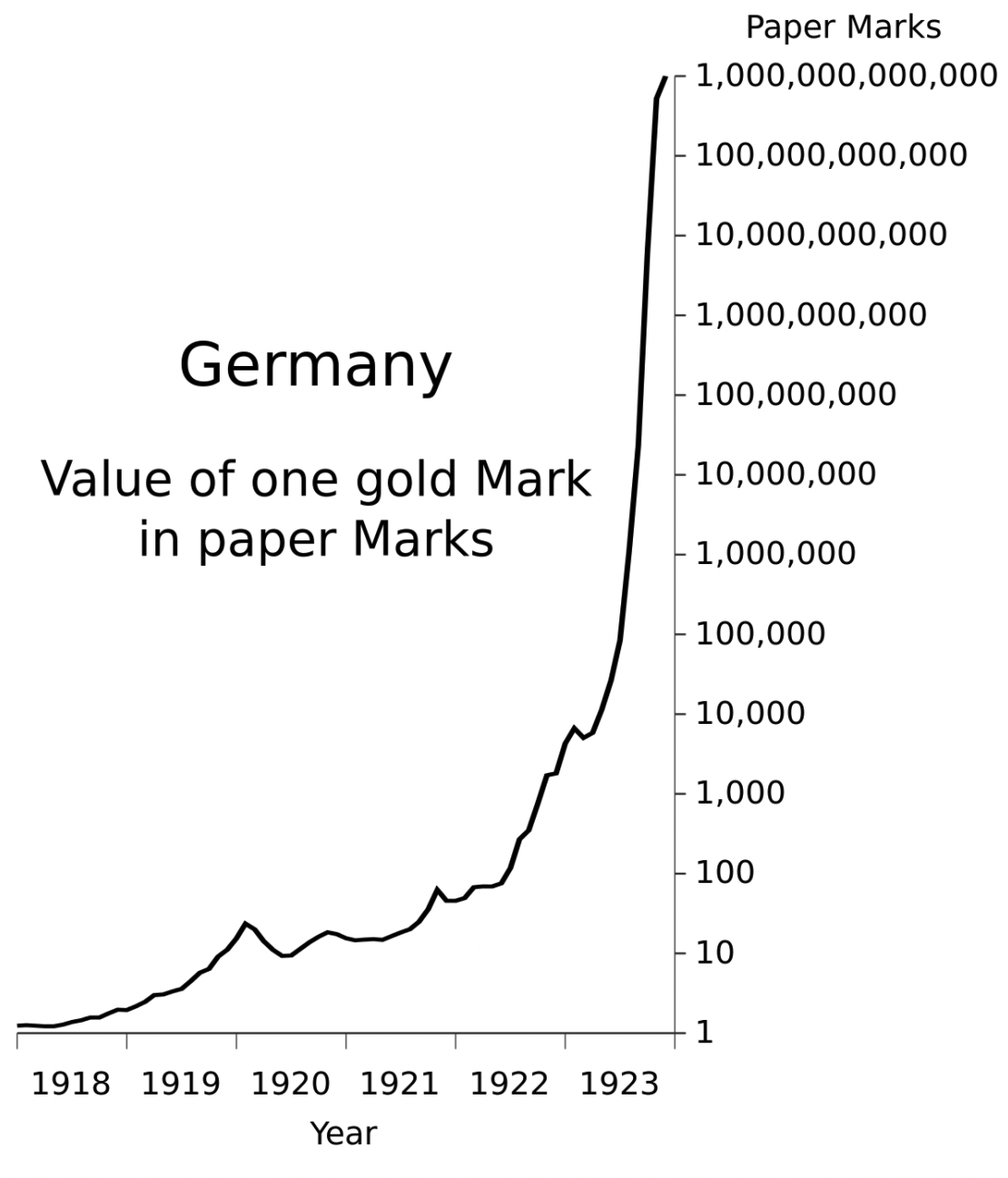

Germany 1923

Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic led to a complete wipeout of wealth following WWI (due to the inability to pay war debts).

This is perhaps the most famous case of hyperinflation in history.

The bad inflationary problems began in 1918 at the conclusion of the war, as war debts had to be paid in gold to prevent the devaluation of these liabilities.

By 1923, the inflation had accelerated into hyperinflation.

China 1949

China’s asset markets closed during WWII.

When communist rule took over in the late 1940s capital markets were destroyed and all financial wealth was wiped out.

Near wipeouts of financial wealth, measured over 20-year periods

We’ll cover near wipeouts of financial wealth looking over 20-year timeframes.

The amount of the decline is put is noted in each case.

Japan: 1928-1948 (-96% decline)

Japan lost WWII and its currency and markets collapsed following their reopening after the war ended.

Inflation went to extremely high levels. Nearly all financial wealth was wiped out.

Austria: 1903-1923 (-95%)

Austria’s inflation problem was similar to Weimar Germany’s but isn’t as well-known historically.

In Austria’s post-WWI case, hyperinflation also nearly eliminated all of the country’s financial wealth.

France: 1930-1950 (-93%)

The combination of the Great Depression of the 1930s and WWII and German occupation in the 1940s led to an extreme market decline and soaring inflation.

Italy: 1928-1948 (-87%)

Like other WWII Axis powers, Italian markets fell significantly after WWII concluded.

A recurring theme throughout history is that losing wars is devastating for a country’s markets and economy.

Italy: 1907-1927 (-84%)

After WWI, Italy faced an economic depression and very high inflation.

The public anger over these countries led to the support for a powerful leader to try to take control of the situation. This led to the rise of Benito Mussolini.

France: 1906-1926 (-75%)

France suffered a domestic currency crisis in the early 1920s, which was inflationary for the country.

Italy: 1960-1980 (-72%)

Through the 1960 to 1980 period, Italy went through a series of recessions, which came with high unemployment and high inflation.

This was also accompanied by currency declines, leading to poor real returns.

India: 1955-1975 (-66%)

India achieved independence in July 1947 after three centuries of British rule.

But its time as an independent country got off to a rocky start after a series of droughts caused economic growth to stagnate and produced high inflation.

Spain: 1962-1982 (-59%)

Spain began a transition to democracy after the death of Francisco Franco in November 1975.

This transition along with the inflation that occurred in the 1970s challenged Spain’s markets and economy.

Germany: 1929-1949 (-50%)

After coming out of the hyperinflationary 1920s, Germany was hit by the Great Depression along with the loss and devastation associated with WWII, leading to another bad period for German financial assets.

France: 1961-1981 (-48%)

During the 1960s and 1970s, France, like other European countries, saw slower economic growth, high inflation, and currency declines.

UK: 1901-1921 (-46%)

The UK went through World War I and the bad economic depression of 1920-21.

Final Thoughts

You’ll notice that the full wipeouts of financial wealth largely had to do with revolutions and war debts that led to hyperinflation.

The near-total wipeouts also had to do with wars – especially losing them.

The main take-home lesson is that diversification is essential.

For example, if you lived through the 1920s, which was largely a period of technological progress, prosperity, and big improvements in living standards in the United States and some other developed countries, you could have never expected what was about to follow with the Great Depression of the 1930s and the major World War that would go on from 1939 to 1945.

Financial history shows that nothing is permanent and things are always evolving.

It’s a good idea to diversify a portfolio through a combination of different:

- assets

- asset classes

- countries

- currencies

No country, no currency, and no system of government lasts forever. Yet almost everyone is surprised, and even devastated, when these shifts happen.

You can protect yourself by diversifying broadly across a range of different instruments in different countries and different currencies.

Currency diversification can also mean forms of commodities, digital currencies, and physical assets.

If 50 to 100 percent of your portfolio is in a certain asset (or asset class) and it gets knocked out, that’s a huge blow. But if it’s a small piece, you can survive it.

For example, with the rise of China coming up to challenge a US-centric world order, is it wise to have everything in the US and dollars and nothing in China and renminbi?

You probably don’t want your portfolio to be concentrated heavily in China. But if you believe in widespread diversification you might not want your allocation to emerging Asia (which goes beyond China) to be zero either.

While things like gold, silver, and other precious metals don’t have an explicit yield to them (technically their yields are negative because of storage and insurance costs), there is more demand for them when traditional financial stores of value (cash, bonds, stocks) see their real returns decline.