Can Unskilled Traders Beat the Markets?

Beating the market is a goal that draws in everyone from hedge fund pros to casual Reddit traders.

Despite overwhelming odds and evidence, many believe they can outsmart a very complex system rife with skilled professionals with massive research budgets who have more information, better analysis, and better technology than a retail trader has.

Can unskilled or purely random strategies actually succeed?

We’ll look at this below.

Key Takeaways – Can Unskilled Traders Beat the Markets?

- Markets are probabilistic – Random success happens often in small samples. Lluck can look like skill.

- Short-term wins mislead – Early success often creates false confidence and risky behavior.

- Skill shows over time – Like sports, poker, or casino games, edge matters over large sample sizes.

- Costs hurt average traders – Fees, slippage, and bad timing make trading a negative-sum game.

- Doom predictors survive on odds – Since markets fall ~40% of the time short-term – e.g., from 26% annual odds to 47% daily odds in US stock markets – so someone always “looks right.”

- Small edges take thousands of trials to prove – A 1% edge needs ~6,700 trades for 95% confidence.

- Random strategies can win briefly – But without structure, they fail over time and are propped up by survivorship bias.

- Should you trade markets? You should only trade markets if you’re willing to spend years developing a real edge. Without one, it’s just an expensive way to feel busy. For non-professionals looking to use markets to support their financial goals, indexing is considered standard best practices.

Markets Are Probabilistic, Not Deterministic

Markets are not deterministic systems. They’re shaped by uncertainty, randomness, and incomplete information.

“Good” outcomes can come from bad strategies by chance.

Experiment

Let’s run an experiment.

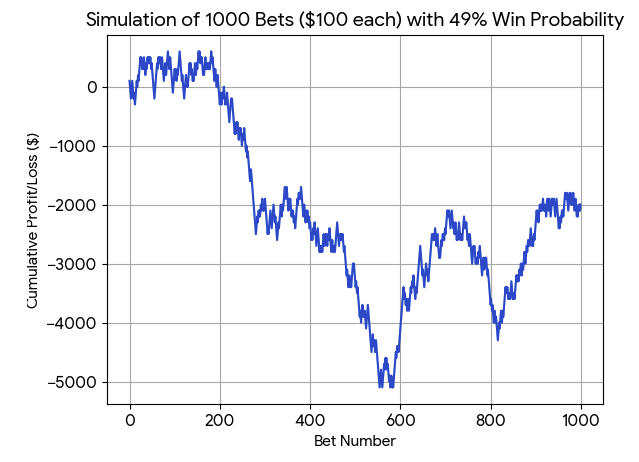

Say we’re a new trader with no edge in the market. We make random day trades, where we have a 49% chance of being right and a 51% chance of being wrong with equal return/loss on each.

It’s a similar type of negative statistical edge that accompanies most uninformed trading.

Each colored line on the plot represents one complete simulation of 1,000 bets of doing this.

From our first run, we were actually profitable over the first 200 or so bets before losing.

Nonetheless, if we had started this experiment just before trade number 600, we would’ve made around $3,000 doing this, and make us look like we have skill that we don’t actually have.

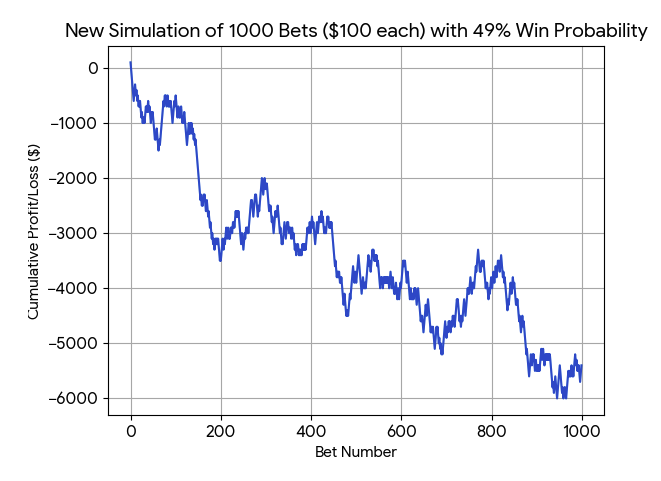

Our second run didn’t do as well.

Pockets of performance

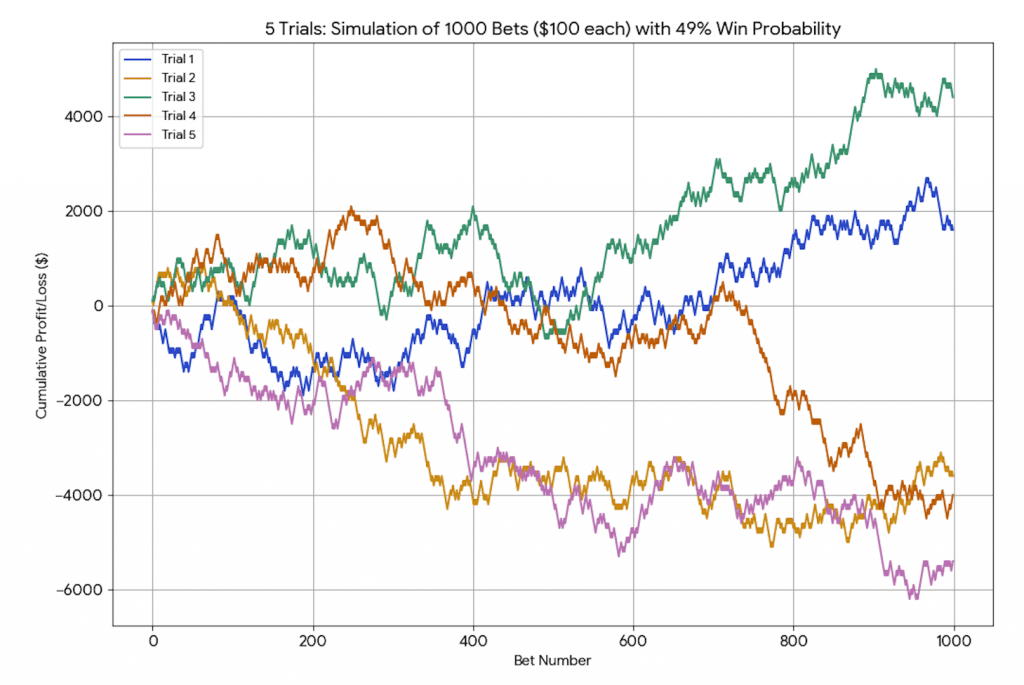

To give a comparative visual, let’s just run 5 simulations at once.

Here, even over 1,000 trades with a negative statistical edge, we were actually profitable in two of them.

As you can see, the outcomes vary significantly from one trial to the next due to random chance.

Variability

Some trials result in more substantial losses than others.

This shows the effect of short-term variance.

Overall Trend

Despite the differences in their paths, it’s clear that the statistical edge and expected value is negative.

In 4 out of the 5, they were either profitable the entire time or for at least 100 trades.

So, while short-term luck can vary, the unfavorable 49% win probability consistently leads to a negative outcome over a large number of bets.

The “house edge,” even a small one, tends to prevail in the long run.

Offsetting Gains and Losses Isn’t a Viable Strategy

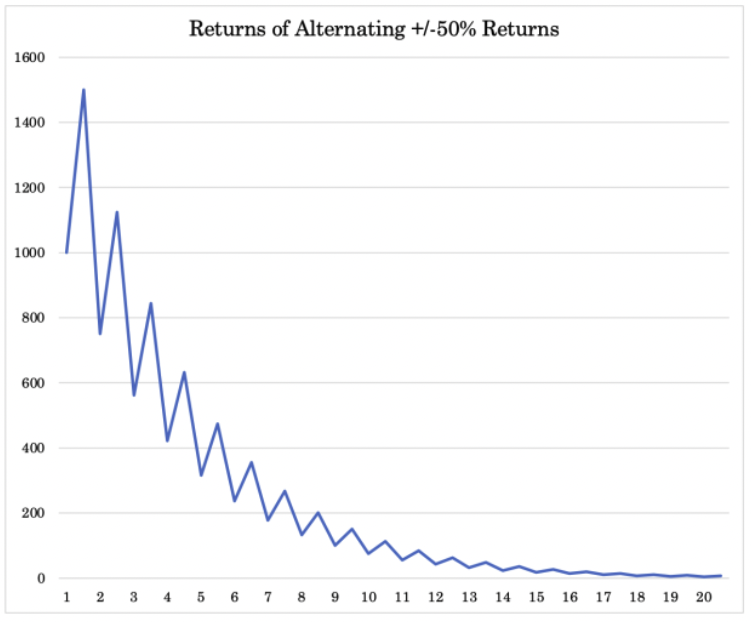

When it comes to drawdowns in the market, another important thing to understand is that equal-percentage gains and losses don’t cancel each other out.

Losing a percentage of a smaller base hurts more than gaining that same percentage helps.

For example, alternating 50% gains and 50% losses repeatedly leads to rapid capital erosion, despite the “balance” of outcomes.

After 10 such rounds, you’d lose about 90% of your money, and after 20, over 99%.

The Illusion of Early Wins in Short Timeframes

In the early stages of trading, it’s not uncommon to see someone with little experience or no clear strategy rack up wins.

This often fuels the belief that they’ve found an edge or have a knack for the markets.

But short-term success can be incredibly misleading.

Just like flipping a coin, even a completely random process can produce impressive results over a limited number of tries.

If you flip a coin ten times, you might get 7 heads. That doesn’t mean you have a special coin or skill; it just means variance hasn’t evened out yet.

For example, many people believe that the odds of getting 60 heads in a 100-flip sample is a lot higher than it is.

People know the odds are 50% and getting 60 seems like a fairly minor deviation.

But the reality is that 60 or more heads in a 100-flip sample has a probability of only 2.8%.

The same principle applies to markets. A trader who bets randomly in a strong bull run might see a string of wins simply because the broader trend lifted all boats.

Their gains aren’t the result of superior analysis or strategy but rather the good fortune of aligning with momentum.

In these moments, luck is easily confused with skill. This is particularly dangerous because it creates false confidence, encouraging more risk-taking without an understanding of the underlying probability.

Monte Carlo simulations are useful for illustrating this illusion. These simulations run thousands of hypothetical outcomes based on random processes, and many show how a small percentage of paths outperform dramatically, even when the average expectation is flat or negative.

In real life, we tend to only hear about these outliers (the lucky few who make it big) while the thousands who lost money quietly disappear.

This creates a skewed perception of what’s likely or repeatable.

Short-term wins are intoxicating, but without a repeatable edge, they are statistically meaningless over the long run.

Time is the great filter. It exposes randomness for what it is and separates sustainable strategies from fleeting luck. For most individuals, this means indexing to the market and getting 50th percentile performance.

Beating the Market Is Like Beating a Pro at Their Own Game

Professional Sports

Imagine stepping onto a basketball court with an NBA All-Star. You’ve never played seriously, but you’re handed a ball and whether you beat them is reduced to a single skill: a free throw contest.

But, an extremely abbreviated one – first one to make a shot wins.

There’s a small but real chance you could actually win, given it’s reductionist and the sample size is curtailed: sink yours and the pro misses (which they do 22-23% of the time in a game, though probably less in practice when they aren’t as fatigued and under pressure).

Most semi-athletic guys could at least hit the rim, if not hit the shot.

Let’s say an amateur with a 50% free-throw accuracy goes against a professional who has a 70% success rate. What are the odds the amateur wins?

In any given round, there is a 50% chance a winner is decided (15% for the amateur + 35% for the pro) and a 50% chance of a tie.

With the amateur’s share of that winning probability 15% and the pro’s share 35% and dividing by the odds of the game ending in each round (50%), that means the amateur’s probability of winning is 30% (.15/.50) and the pro’s is 70% (.35/.50).

That’s quite high.

If that happened, would the amateur walk off the court thinking you were the better player?

That’s what it’s like when an unskilled trader beats the market over a short time horizon.

In a single, narrow sample, randomness can hand the amateur a win.

The market, like sports, is a probabilistic game, not a deterministic one. Surprises happen. But surprises aren’t the same as skill.

Poker

Let’s extend the analogy to poker. A casual player could beat a professional in one hand, even one evening. Give them favorable card luck (e.g., pocket pairs, the chance to hit overpairs), have a few coin-flip hands go their way, and the chips might pile up.

Over the sample size of a single hand, a top professional poker player won’t have much more than a low-50%’s edge over a casual player who knows the rules and not much more.

But stretch the game across thousands of hands, and the edges become visible.

Professionals aren’t guaranteed to win every session, but they’ve built systems around statistical advantage, money management, and psychological edge.

Over time, they grind out a profit. The casual player gets ground down. To pros, it’s one big long session.

Markets are no different. Over short stretches (days, weeks, months, quarters… and even the annual can be noisy) a trader with no real edge can look good.

Maybe they piled into a hot stock right before it surged. Maybe they followed someone on social media who got it right this time. Maybe they guessed the market would fall, and they sold and lucked out.

Whatever the reason, early success can feel validating. It can make randomness look like insight and luck feel like control or skill.

But this illusion collapses when you zoom out. Professionals who beat markets consistently don’t rely on hunches. They use models, data, discipline, and risk control.

Their strategies aren’t perfect, but they tilt the odds in their favor. Over hundreds of trades, those small edges add up.

For the unskilled trader, the opposite happens: costs, bad timing, emotional decisions, and lack of edge erode capital slowly and surely.

Casino Games

It’s also worth thinking about casinos. Everyone knows the house has the edge and playing casino games isn’t a reliable way of making money.

You can win at roulette on any given spin. You can walk out ahead after a night of blackjack.

But no serious person believes they can beat the casino in the long run by randomly playing games of chance. The negative edge (for customers) is baked into the way the games are set up. The longer you play, the more likely you are to lose.

Markets

Now, given what we just covered in the casino game analogy, bring that mindset to financial markets. Many assume markets are different: fairer, more beatable. But the underlying statistical nature of it is very similar.

Not with respect to indexing, but trying to beat the index, which means outperforming and taking money away from professional investors.

Markets are adversarial. There’s someone on the other side of the trade who is probably relatively sophisticated and there’s a reason why they’re doing it.

The trade was most likely (but not always) triggered because of machine that can process a lot more information, a lot more accurately, a lot faster, and a lot less emotionally than any given person could hope to do.

It’s just their edge working for them and working against any retail trader serving as their counterparty.

Markets are full of professionals with superior information, better analysis, better technology, faster execution, and deeper research budgets.

The “house” in this case is made up of hedge funds, market makers, and institutional investors who understand the rules better than their competition.

If you’re making decisions without edge, you’re playing their game on their terms.

Of course, the big difference between markets and poker or roulette is that the edge is harder to measure and not as obvious. That makes the illusion even more dangerous.

You can convince yourself you’ve got skill or foresight because a few trades worked out and develop dangerous hindsight bias.

But it’s the same as thinking you’re ready for the NBA after one lucky free throw.

In the end, it comes down to time and volume. Over small samples, almost anything can happen. Over large ones, edge and discipline prevail.

Beating the market isn’t impossible, but it’s extremely difficult. Not because it’s unfair, but because it demands skill that only reveals itself over the long haul.

Just like in sports or poker, if you’re serious about winning, you need more than a lucky shot. You need a system that exploits edge in a repeatable way over time.

For most individuals, that means simply indexing to markets and collecting the earnings of profitable companies over time.

What Are the Odds That the Market Will Fall Over Various Timeframes?

If you’ve ever been on financial social media, you know there are many people with hot takes about how they think the market will fall.

Here’s a summary of historical odds that the US stock market (typically the S&P 500) shows a negative return over different time horizons going back approximately 100 years:

Probability of Negative Return

| Holding Period | % Negative Return | % Positive Return |

| 1 day | 46.9% | 53.1% |

| 1 week | 44% | 56% |

| 1 month | 37.2% | 62.8% |

| 1 quarter | 31.3% | 68.8% |

| 1 year | 26.1% | 73.9% |

Shorter investment horizons see nearly 50/50 odds and are subject to volatility.

If an asset has a 7% expected yield per year, that’s 0.02% on a daily basis. Stocks, as a standard deviation, have 1% volatility per day. That’s a 50x noise-to-signal ratio.

As your timeframe lengthens, the probability of positive returns increases significantly, reflecting the market’s long-term upward drift because the stock market is comprised of businesses that largely produce profits, and these profits lead to capital gains and dividends/distributions.

These Odds Sustain the “Market Will Crash” Crowd

These odds help explain why the “market is going to crash” crowd never goes away. On any given day, the market has about a 47% chance of being negative, nearly a coin flip.

Over a week or month, the chance of a negative return is still sizable: around 37% to 44%.

That kind of randomness means that someone, somewhere, will always “be right” about a drop, even if it was just luck or vague timing. And that keeps the doom-commentator ecosystem alive and well.

Most of these voices don’t actually offer structured analysis. They rarely explain the why, they don’t tie their calls to any kind of market understanding (outside reading headlines when all known information is already priced in), and they almost never give a defined timeframe.

It’s usually a generic, gut-feeling statement like “the market feels frothy” or “something’s got to give,” which don’t add any value.

If the market falls tomorrow or next week, they claim victory. If not, they say “just wait.”

This works because the market does go down sometimes, and they rely on that inevitability, not insight.

But when you zoom out to a one-year horizon, the odds flip dramatically. The US stock market has ended the year higher about 74% of the time.

That means your chance of a loss is still better than flipping heads twice in a row. So while bearish predictions may occasionally be correct in the moment, they’re statistically bad bets when left vague and open-ended.

This is the trap: the loudest voices often focus on the short-term coin flips while ignoring the long-term odds.

And as long as markets remain probabilistic, there will always be someone calling for a fall; sometimes right, usually lucky, rarely skilled.

The Danger of Hindsight Bias

When traders guess right, hindsight bias kicks in: they believe they “knew it all along,” reinforcing overconfidence.

When they guess wrong, they rationalize it away: bad luck, unexpected news, or timing issues. Or they simply forget that their gut was wrong.

This selective memory fuels illusion of skill or foresight when it wasn’t.

Over time, these biases distort judgment, making it harder to see whether they actually have edge or are just spinning the psychological roulette wheel and getting fooled by noise.

The Long Game in Proving Edge

In the short term, almost anything can happen in markets. A bad strategy can look brilliant. A coin-flip trade can double your money. And randomness can deliver both big wins and crushing losses to traders with no real skill.

But stretch the timeline, and the picture changes.

The longer you stay in the game, the more the odds assert themselves, and the more a trader’s actual edge, or lack of one, becomes visible.

This is where the law of large numbers comes in.

Over time, statistical noise (the random swings, lucky streaks, and fluke trades) starts to cancel out. What remains is the true average outcome of a strategy.

If your trading system has a small positive edge, time works in your favor. If your strategy is flawed or if you’re just guessing, time works against you. The more trades you make, the more likely your results will align with your actual expected return, not the lucky exceptions.

Think of a casino. In the short run, a roulette player might walk away with profits. But over thousands of spins, the house edge guarantees the casino will come out ahead.

The math is embedded in the structure of the game. Markets are different in that they aren’t purely games of chance, but the principle still applies.

Professionals who manage risk, execute well, and have a repeatable process can grind out long-term gains. Amateurs chasing hunches and headlines often revert to the mean, and the mean isn’t kind to random traders once costs and slippage are factored in.

Time is the great equalizer. It exposes strategies that are built on substance and discipline, and it slowly erodes those built on luck.

While it’s possible to look smart for a while using weak or random approaches, eventually the numbers catch up.

Over a long enough horizon, edge isn’t optional; it’s essential. Without it, the game becomes a slow bleed if you’re operating with a negative edge.

How Professionals Tilt the Odds

In markets, professionals build systems. Their advantage starts with data; not just the public kind, but deep, real-time feeds, institutional research, and massive datasets that let them detect patterns before others can.

They have the means to analyze these signals quickly and objectively, while most amateurs are reacting emotionally to headlines or price spikes.

Professionals also have capital on their side. With more capital, they can diversify across uncorrelated trades, size positions appropriately, and weather short-term losses without being forced to sell.

This gives them staying power, while many retail traders get wiped out by volatility before a trade plays out.

Add in market access, like faster execution, better order routing, and access to dark pools or OTC flows, and the advantage gets even wider. These edges may seem small individually, but they compound in ways that matter.

Perhaps most importantly, professionals operate with risk models and rules. They don’t bet based on a hunch. They think in probabilities, not “predicting the future.”

They know their maximum drawdown, they size trades appropriately, and they cut trades when things change.

Amateurs, on the other hand, often trade without rules. They double down after losses, chase heat, and overexpose themselves to single names or market themes.

The lack of structure leaves them vulnerable, not just to bad trades, but to their own impulses.

This is where the real divide lies: professionals systematically tilt the odds, turning edge into outcome over time. Amateurs, even when lucky, are swimming against a current of costs, slippage, taxes, and suboptimal execution.

Random success in the short term can’t overcome those long-term structural disadvantages. Without a repeatable process and a way to manage risk, randomness fades, and the market reclaims what it gave. Professionals understand this.

Embedded Negatives: Why the Average Trader Loses

Even in a perfectly fair market, most traders still lose, and it’s not just about bad picks. It’s the math.

Every trade comes with embedded costs: commissions, bid-ask spreads, slippage, and sometimes taxes. These small charges eat away at returns, especially for active traders making frequent moves.

For example, if you buy at the ask and sell at the bid, you lose a fraction of a percent instantly, even before price moves. Do that hundreds of times, and the drag becomes significant.

Then there’s timing. Most retail traders buy high, when hype peaks and sell low, when panic sets in. It’s not malice, it’s human psychology: fear, greed, and overconfidence.

These behavioral traps create negative expected outcomes, even when market direction is positive.

Meanwhile, professional players have lower transaction costs, better execution, and more disciplined timing. That gives them structural efficiency, while the average trader bleeds edge through friction and emotion.

In theory, the market is a place where anyone can win. In practice, it’s like running a race with weights on your ankles. Unless you have a clear edge and control your decisions, the invisible forces (fees, spreads, bad timing) slowly grind down your capital over time.

Can Random or Naive Strategies Ever Win?

It might seem absurd, but sometimes, random or naive investment strategies actually produce decent returns, at least over certain timeframes.

This has been shown in multiple studies, like the well-known “monkey portfolio” research, where portfolios built by random stock selection performed as well as or better than those managed by professionals.

Equal-weighted portfolios have also outperformed market-cap-weighted ones at times, simply because they force regular rebalancing and reduce concentration risk.

Even simple momentum-following systems – like buying recent winners and selling recent losers – have historically shown excess returns in certain regimes.

So what gives? If markets are competitive and filled with smart players, how can randomness or simplicity sometimes win?

The answer lies in timeframe and market regime. Over short periods, noise can dominate signal. A naive strategy might randomly align with a rising sector or trend.

Our earlier example (i.e., simulating 1,000 bets with a 49% win probability) showed how luck can string together temporary gains. Over 10 or 20 trades, even a bad strategy can look brilliant.

But scale it up to 1,000 trades or more, and the statistical edge (or lack thereof) starts to reveal itself.

The same principle applies to portfolios. A randomly built basket of tech stocks might outperform the market during a tech boom, but that doesn’t mean randomness is a replicable strategy.

Eventually, a market shift exposes the lack of structure. Without consistent logic or edge behind selection and risk management, randomness gets punished when regimes change or volatility spikes.

There’s also the illusion factor. We often hear about the one naive portfolio that beat the market, but not the hundreds that quietly failed. Survivorship bias has a huge role in amplifying these anecdotes. Unskilled success tends to be an anomaly, not a sustainable pattern.

That said, some “naive” strategies (like equal-weighting or basic momentum) may work not because they’re random, but because they unintentionally tap into deeper structural behaviors in markets. They’re simple, but not necessarily dumb.

In the end, yes, random or naive strategies can win, but the key question is: for how long, and under what conditions?

Without edge, discipline, and a clear framework, it’s only a matter of time before randomness reverts to the mean, and the mean is rarely kind.

Conclusion: Luck, Skill, and the Hard Truth of Market Survival

Over the short term, randomness may shine. But in the long run, persistent, structured, repeatable edge wins.

If you’re unskilled, your odds shrink with every trade you place. In that sense, it’s not unlike training for a sport or becoming good at any other career.