Why Most Traders Lose Even When They’re Right

All traders know the feeling of being right but still losing money.

It’s one of the most frustrating experiences in the markets – your analysis is solid, your direction is correct, yet somehow your account balance shrinks instead of grows.

What’s the basis behind being right and still not making money?

And how do we fix it?

Let’s take a look.

Key Takeaways – Why Most Traders Lose Even When They’re Right

- Poor Timing

- Position Sizing Errors

- Leverage Misuse

- Unrealistic Return Targets

- Stop-Loss Problems

- Risk Management Failures

- Impatience & Early Exits

- Letting Winners Turn into Losers

- Holding Costs & Decay

- Overtrading

- Transaction Costs & Slippage

- Emotional Decision-Making

- Lack of a Systematic Approach

- Time Horizon Mismatch

- Ignoring Volatility

- Correlation & Hedging Errors

- Market Context Blindness

- Market Structure & Competition

- No Exit Plan

The Costly Gap Between Being Right and Making Money

Poor Timing

Timing is one of the most common reasons traders lose money, even when their analysis is correct.

The market may move in the direction a trader predicted, but if the entry or exit point is poorly chosen, the trade can still result in a loss.

An example would be buying a stock after it’s gone up when their thesis is based on valuation.

When it comes to day trading or shorter timeframes, entering too early often leads to getting stopped out by normal price fluctuations, as markets never move in a straight line.

Even in strong trends, pullbacks are common, and these temporary moves can shake out traders who were technically “right” but positioned ahead of the real move.

On the other hand, entering too late can be just as damaging.

Traders who wait until the move feels obvious often end up buying near the top or selling near the bottom, capturing only the final part of the trend before it reverses.

This problem is often fueled by emotions, such as fear of missing out, which pushes traders to jump in at the wrong time.

Exits are equally sensitive to timing. Selling too soon can cut off the majority of a winning trade, while holding too long (e.g., a concern for some momentum traders) can allow gains to evaporate as the market reverses.

In both cases, the trader may have been right about direction, but their execution robbed them of profit.

Good timing requires patience, discipline, and a clear plan. Many times it’s automated since it can be so difficult for a human/discretionary trader.

Traders often improve results by waiting for:

- confirmation signals (for a technical trader, e.g., a moving average crossover, a break of resistance, a higher low forming, volume expansion, a bullish candlestick pattern, or RSI divergence)

- aligning with broader market context, and

- defining exit levels before entering

In short, it’s not enough to know what direction the market will go; success comes from mastering when to get in and out.

Position Sizing Errors

Position sizing is one of the most overlooked aspects of trading, yet it often determines whether a trader survives long enough to capitalize on being right.

It’s also something that you tend to make enough errors to the point where:

- you always size small (safe, but sometimes suboptimal)

- you learn how to better optimize, often in a logical mathematical way

When a trade is oversized, normal market fluctuations feel terrible. Volatile markets are basically impossible.

A small dip against the position can create a drawdown large enough to force an early exit or even wipe out a significant portion of your capital.

The stress of watching losses build often leads to poor decisions that compound the damage and you have the emotions of all that.

At the opposite extreme, undersizing positions has its own cost – i.e., the cost of foregone gains from being too conservative.

A trader might correctly identify several strong moves, but if the position size is too small, the profits never accumulate enough to offset inevitable losing trades.

Trading is a game of probabilities, and the math requires that winners meaningfully outweigh losers over time. Undersized trades sabotage this balance.

The core of position sizing is consistency and proportionality.

And it all depends on the trading goals and time horizon:

- Many professionals risk a fixed percentage of capital on each trade, often between one and two percent.

- Others have more static portfolios and go larger on their position sizing since they’re holding over months or years.

- Some believe in diversifying and granulating the position sizes so that no individual position has much of an effect (even longer term holders).

- Some believe in putting the bulk of a portfolio into a handful of a “A” ideas and allocating less (or even nothing) to “B” and “C” ideas.

Concentrated portfolios will often still have specific risk management rules.

This approach is done so no single loss cripples the account, while winners have the ability to compound over time.

The discipline of correct sizing removes much of the emotional turbulence from trading.

Ultimately, success depends not just on predicting the right direction, but on structuring positions so that gains outweigh losses in the long run.

Leverage Misuse

Leverage is one of the most tempting tools in trading, but it’s also one of the most destructive when misused (and it usually is without experience and painful lessons along the way).

By borrowing capital to control a position larger than their account size, traders can magnify profits from small price movements.

The problem is that leverage works both ways.

The same small movement against the position can create losses large enough to trigger margin calls or force liquidation, often before the original thesis has time to play out.

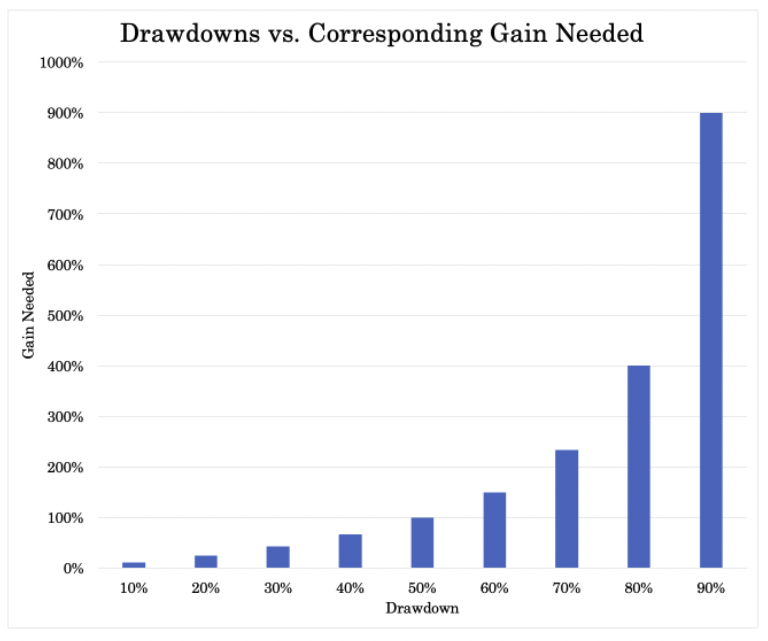

The mathematics of recovery also turn against overleveraged traders.

A 10 percent loss requires just over 11 percent to recover, but a 50 percent loss requires a 100 percent gain.

It progressively becomes more extreme.

With high leverage, it only takes normal market volatility to inflict devastating drawdowns that are almost impossible to come back from.

Many traders who are “right” about direction end up broke simply because their positions were too large to withstand short-term noise.

Used with discipline, modest leverage can be great for capital efficiency. But when treated as a shortcut to fast profits, it nearly always accelerates failure.

Sustainable trading requires respect for risk, not the illusion of easy magnification.

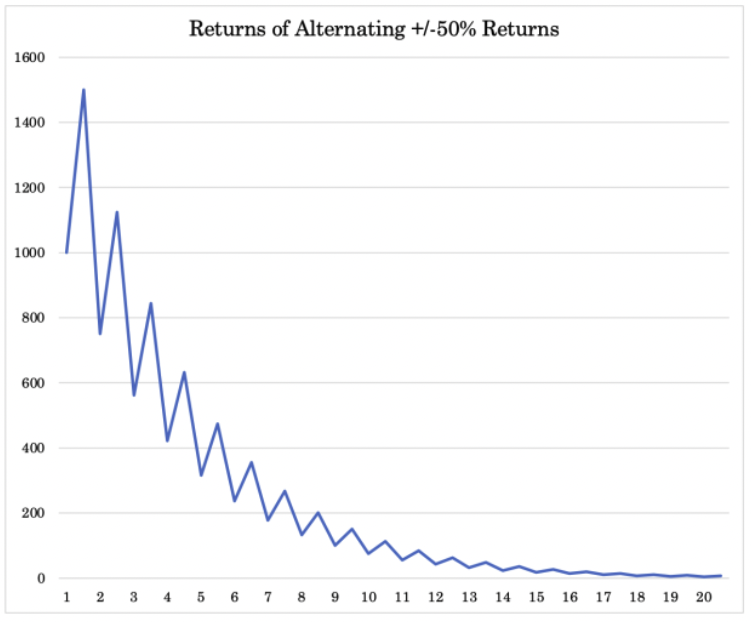

You also can’t simply alternate between equally good returns and losses and be okay because the math of that works against you.

Unrealistic Return Targets

Many traders see bad returns even when they’re right because they set return expectations that far exceed what the market can reasonably deliver.

Remember that stock indexes generally don’t return better than 6-10% per year long-term. Yet some think they can make that every month. It’s not realistic.

If you make 6% per month, on a compounded basis that’s about 100% per year.

If you start with $25,000 and earn 6% per month (~100% per year compounded) for 25 years, that’s $839 billion. It’s probably not going to happen.

Some use leverage to help them, but injudicious use always ends badly.

Using leveraged instruments like S&P 500 futures provides exposure to a broad basket of stocks with relatively low collateral requirements, but the risks are severe when not properly capitalized.

Without sufficient capital, drawdowns quickly become unmanageable.

Chasing outsized returns often leads to overleveraging, where even normal volatility wipes out accounts.

It’s not volatility itself that destroys traders. Volatility is great if the market is moving your way. But it’s the inability to manage the downside, the “left tail” of risk.

Realistic goals, backed by discipline and adequate capital, are far more sustainable than chasing impossible numbers.

Stop-Loss Problems

Stop-losses are important in certain trading styles, but misusing them often turns good ideas into losing trades.

Stops set too tight are triggered by normal market noise, cutting trades that might have worked.

Stops set too wide expose accounts to damaging losses. Some traders make things worse by shifting stops further away in hope of recovery, and abandoning discipline.

Effective stops require balance, consistency, and the courage to accept small losses.

Risk Management Failures

Risk management is the foundation of trading, yet most of the focus is on producing “offense.”

Many traders spend hours analyzing markets but give little thought to how much capital they are risking on each idea.

This imbalance can be fatal. Risking too much on a single trade means that one wrong move can erase weeks or months of steady progress.

Even when a trader is right most of the time, it only takes one outsized loss to undo the entire record.

Another frequent error is failing to diversify. Concentrating too heavily in one position, sector, or asset class magnifies exposure to unexpected events.

A sudden news release, policy change, or market shock can wipe out concentrated portfolios regardless of how accurate the original thesis was.

There’s always stuff that you can’t control.

Equally damaging is ignoring maximum drawdown limits.

Without predefined thresholds for stepping back or reducing exposure, traders often keep pressing forward until losses spiral out of control.

Strong risk management doesn’t/can’t eliminate losses, but it does mean they can remain small and survivable.

Successful traders think first about protecting capital. What’s the worst that can happen and then go from there.

Profits come from consistency, but consistency only exists when risk is carefully measured, limited, and controlled over time.

Impatience & Early Exits

Impatience is one of the most common traps in trading. Many traders enter with a well-reasoned thesis but fail to give the market enough time to validate it.

Exiting too soon often stems from fear – i.e., fear of giving back small gains or fear of watching a profitable position slip into a loss.

This defensive instinct might feel safe in the moment, but it leaves the real move untouched.

Markets rarely move smoothly, and temporary pullbacks are a normal part of any trend.

Traders who mistake these short-term fluctuations for reversals often cut winners before the larger payoff arrives.

The result is a pattern of many small profits that never outweigh the occasional bigger loss. Over time, this erodes confidence and sabotages even sound strategies.

Patience requires discipline and trust in one’s process. You have to set clear targets and commit to them and give your thesis the chance to fully play out.

Lasting success depends not just on identifying direction, but on staying the course long enough to capture it.

Letting Winners Turn into Losers

Traders often hold on, hoping for “just a bit more,” only to watch the market reverse.

What looked like a winning position quickly becomes a loss.

The psychology is tricky; rising prices make trades look more attractive, but they’re also often becoming more expensive.

Taking profits systematically or scaling out protects gains before they disappear. Discipline preserves progress.

Now after what we’ve just covered over the past two subheadings, you might think this sounds contradictory: first I said let trades run, now I’m saying don’t let them run too far.

The key is logical and consistent application of your rules that have been well stress-tested.

It’s not about guessing in the moment, it’s about applying a tested set of rules with discipline every time.

Holding Costs & Decay

Many traders underestimate how much holding costs can erode profitability, even when they are correct on market direction.

Every financial instrument carries a built-in cost of carry, and if those costs outweigh the eventual gain, the trade ends in disappointment.

Options, for example, suffer from time decay.

Even if the underlying asset moves as expected, the option’s value may shrink day by day as expiration approaches.

Traders often find themselves right on direction but still losing money because the clock worked against them.

Margin trading introduces another layer of expense. Borrowed capital carries interest, and these charges accumulate quickly if positions are held for weeks or months.

What looks like a small daily rate can quietly consume a meaningful portion of profits.

Futures contracts add their own complication with rollover costs, plus the built in margin costs. When contracts approach expiration, traders must exit or roll into the next month, often at less favorable prices.

These frictions make timing and instrument choice critical.

It’s not enough to predict direction; traders have to consider whether the potential gain exceeds the cost of staying in the trade.

Ignoring holding costs transforms good analysis into less-than-expected results. Awareness and planning keep profits intact.

Overtrading

Overtrading is a silent drain on many trading accounts.

The temptation to chase every market move often stems from boredom, fear of missing out, or the false belief that more trades equal more profit.

In reality, each transaction carries a cost (spreads, commissions, and slippage) that steadily erodes returns.

While a single trade’s cost may seem insignificant, frequent activity compounds these expenses into a heavy drag on performance.

Even traders with a high win rate can struggle if their profits are constantly being chipped away by these frictions.

A strategy that looks profitable on paper may collapse once execution costs are factored in.

Beyond the financial damage, overtrading also dilutes focus and conviction. Entering too many positions at once reduces the ability to manage each one properly, increasing the odds of mistakes.

The solution is discipline. Quality matters far more than quantity.

Waiting for high-probability setups and controlling frequency helps traders preserve their edge and keep transaction costs from consuming their hard-earned gains.

Transaction Costs & Slippage

Transaction costs and slippage quietly undermine many trading strategies.

On paper, a trade may look profitable, but once spreads, commissions, and execution delays are factored in, the outcome often shifts to a loss or is just less profitable than what it initially appeared.

Futures have the built-in margin costs.

Retail traders are especially vulnerable because they lack the speed and pricing advantages of institutions.

Wide bid-ask spreads, slow order fills, and hidden platform fees all add friction that eats into returns.

Slippage, when orders are filled at a worse price than expected, is another common problem, especially in fast-moving or thinly traded markets.

Even small differences accumulate over time and can gradually eroding a strategy.

A strategy that relies on tight margins or frequent trades is particularly at risk, since execution costs can outweigh any edge.

Successful traders build these realities into their planning, backtesting, simulations, and stress testing so expected profits exceed the inevitable costs of participation.

Emotional Decision-Making

Harmful emotions are among the greatest obstacles to consistent trading performance.

Market analysis can be logical and structured, but execution often falters when fear and greed take over.

Fear tends to show up in two ways: cutting winners too early and hesitating to enter valid setups. Or liquidating when there are blips along the way (often when it’s best to keep holding).

Traders who exit at the first sign of a pullback miss the larger move their thesis predicted, while those who hesitate may chase later at worse prices.

Greed is just as destructive. It tempts traders to hold on to losers far longer than planned, hoping the market will eventually turn.

It also encourages overextending into larger positions after a string of wins, creating outsized risk exposure at precisely the wrong moment.

Overconfidence after success often sets the stage for the next major setback.

Another emotional trap is revenge trading – i.e., doubling down or taking impulsive trades after a loss in an attempt to “get it back.”

Instead of recovering, this usually accelerates losses.

These patterns aren’t caused by poor analysis, but by poor control over psychology.

Disciplined traders combat emotional decision-making with predefined rules: entry criteria, stop-loss placement, position sizing, and exit strategies established before the trade.

This is why most trading in most liquid markets is algorithmic these days and the percentage goes up over time.

In the most liquid global markets, algorithmic trading accounts for 60-75% of all trading volume, rising from just 15% in 2003 to over 70% by 2010 in US equities, with a similar growth pattern seen in Europe and Asia. The percentage continues to climb due to AI, high-frequency trading, and broader market digitalization.

In the end, you have to rely on structure rather than impulse.

Lack of a Systematic Approach

A common reason traders lose despite being correct is the absence of a clear, repeatable system.

Many approach the market with shifting strategies: one week relying on technical indicators, the next reacting to news headlines, and later chasing a tip or a sudden move.

This inconsistency prevents any edge from developing. Even accurate analysis becomes useless when it is applied haphazardly.

Trading thrives on structure. A systematic approach means having predefined rules for entries, exits, risk limits, and position sizing.

These rules provide consistency across trades and remove much of the emotional noise that leads to poor decisions.

Without them, traders fall back on gut feel, often mistaking random market fluctuations for opportunity.

And their feedback systems will be permanently broken under this approach. When the market moves in the direction they claimed to foresee, it’s “I knew it”; when they lose, they were just unlucky or it’s the fault of somebody or something else.

Another danger lies in constantly abandoning a method after a few losing trades. No system wins every time. Chasing the newest signal or strategy resets progress and prevents the compounding effect of a disciplined process.

Successful traders build a framework they trust, test it thoroughly, and stick with it when it’s proven.

You can never eliminate risk, but you can control it and it transforms trading from a series of random guesses into a structured process.

Time Horizon Mismatch

One of the most frustrating ways traders lose despite being correct is by mismatching their time horizon with their instruments.

A trader may have a solid long-term thesis, but if they express it through short-term vehicles, such as weekly options or near-dated futures, they risk being forced out before the move unfolds.

Expiry dates, rollover costs, and short-term volatility can cause your trade to not pan out, even if the bigger picture plays out.

To align analysis with the execution part, it’s important to choose instruments that match the intended holding period.

Without this alignment, correct forecasts turn into losses driven by timing mechanics rather than faulty logic.

Ignoring Volatility

Many traders focus only on direction, overlooking volatility.

In options trading, for example, a correct forecast on price can still lose money if implied volatility does something you didn’t plan for.

If you’re holding a long-dated option with implied volatility priced at 35% and it falls to 17%, that’s a large fall in price looking only at the implied volatility effect.

The premium paid for the option erodes, leaving the trader with less even as the underlying asset moves as expected.

Futures traders face a different problem: volatile, choppy markets that trigger stop-losses or force exits before the trend resumes.

Misjudging volatility skews risk-reward and distorts position sizing.

A trade that is directionally correct can still bleed capital if volatility behaves differently than expected.

Successful traders account for both price movement and volatility dynamics when planning entries, sizing positions, and managing exits.

Correlation & Hedging Errors

Hedging and correlation management are important considerations for professional traders, but they are also common sources of losses when misapplied.

The idea behind a hedge is straightforward: offset risk in one position by holding another that should move in the opposite direction.

In practice, however, hedges often fail to behave as expected when they aren’t exact.

Sometimes the hedge loses more than the main position gains, leaving the trader worse off than if no hedge had been placed at all.

Sometimes the cost is too much.

For example, if you own $650,000 worth of S&P 500 futures, a 1-year hedge to protect against a 20% fall could cost around $10,000, or close to 2% of the position. It can be worth it for some, but it’s also expensive.

A common problem frequently comes down to correlation. Traders assume two assets are negatively or positively correlated, but correlations shift over time – especially in the tails (i.e., often break down under stress).

For example, a trader long equities might go long bonds as a hedge, expecting them to move inversely.

Yet in certain environments, such as stagflation, stocks and bonds can fall together, turning what seemed like a protective strategy into a double loss.

Even subtle correlation errors can be damaging. A portfolio with multiple “diversified” positions may in reality be heavily exposed to the same underlying driver, like interest rates or energy prices.

When that driver moves sharply, all positions suffer at once.

Effective hedging requires more than intuition. You need ongoing analysis of how assets interact under different market environments and under possible stress tests, as well as an understanding of tail risk when normal relationships break down.

Traders must recognize that a hedge introduces its own costs and risks. You pay the volatility risk premium when it’s constructed in the form of options and that can be a long-run drag.

The most successful traders use hedges selectively, size them carefully, and constantly reassess correlations so they remain valid.

Without this discipline, even traders who are right on direction can find their profits erased by misaligned protection.

Market Context Blindness

A trade can look good in isolation yet still fail if the broader market environment is unfavorable to it.

Many traders focus narrowly on individual setups without considering macro conditions such as interest rates, index trends, or overall risk sentiment.

A stock may show a strong technical breakout, but sector-wide pressures or global events can lessen the probability of success.

Ignoring context blinds traders to forces larger than their own ant hill.

Successful trading requires aligning individual ideas with the wider backdrop.

When factoring in market direction, sentiment, valuation, and economic drivers, traders can increase the odds that their setups work with a broader framework.

Market Structure & Competition

Retail traders often underestimate how market structure favors institutions and specialized execution algorithms.

Professional players benefit from faster execution, deeper liquidity, and tighter spreads, while individuals face higher slippage and delayed fills.

These small disadvantages accumulate, and it’s why the odds of each individual trade working out are generally less than 50%.

Even when retail traders correctly predict direction, structural frictions erode their edge.

Understanding these limitations is important to adapting strategies that can survive against stronger competition.

Short-term strategies can definitely work, but can be harder to pull off. This is also why traders tend to increase their timeframes as they gain more experience.

No Exit Plan

Many traders devote a lot of energy to finding the perfect entry but neglect to define how and when they’ll exit.

Without predetermined profit targets or trailing exit strategies, how do you know when to bank your gains?

Traders who lack a structured exit plan often find themselves unsure whether to hold on for more or cut the trade to protect what little remains.

The opposite problem occurs during temporary pullbacks. Without clear rules, traders have a tendency to panic-sell at the first sign of noise, turning potential winners into small gains or even losses.

Successful trading requires as much discipline in planning exits as in choosing entries.

Whether it’s scaling out at set levels, using trailing stops, or locking in profits at key milestones, defined exit strategies provide structure.

In the long run, consistent exits transform good analysis into realized gains.

Conclusion

So, how can we boil this down…

We know that being right on direction isn’t enough. Poor timing, wrong instruments, or mismatched horizons can still turn good analysis into losses.

Capital preservation matters more than big wins. Improper sizing, leverage misuse, or lack of risk controls quickly erode accounts. It’s not easy to know this without trading experience since you always want to play offense first and defense/risk management is boring.

Costs compound quietly. Transaction fees, holding costs (e.g., margin), and slippage steadily eat into returns, especially for frequent traders.

Discipline separates winners from losers. Impatience, greed, fear, and emotional trading destroy otherwise solid ideas.

Consistency and structure are critical. Without tested rules for entries, exits, and risk, profits slip away even when the call is correct.