How to Navigate Paradigm Shifts in Financial Markets

Paradigm shifts occur when markets over-extrapolate one set of conditions into the future despite those conditions being unsustainable.

The last decade and even the last 40 years are what traders and other market participants think will probably hold. However, that could easily be wrong because we’re now in a totally different world.

If you take the forces of:

- falling nominal interest rates that have been the case since the early 1980s

- falling real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates, financialization, and

- globalization…

…all of those arcs have largely played out despite being a big key in how markets have performed over the past four decades or so.

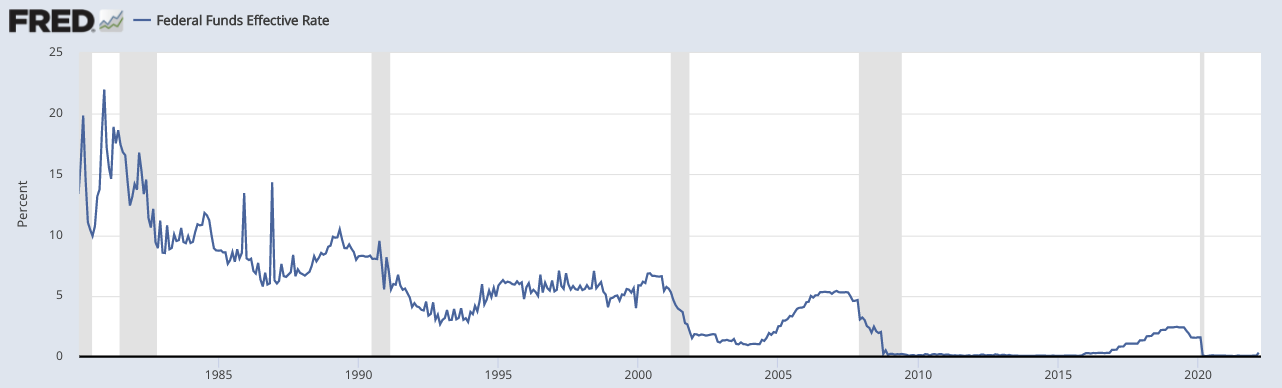

We’ve had a steady decline in interest rates in the US and other developed markets over the past 40+ years and interest rates are no longer a good mechanism to get more credit into the system to help offset economic weakness.

Federal Funds Effective Rate

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

These forces have largely reached their limits and are going in the opposite direction.

Traders are grounded in these experiences as we’ve lived through them, though the past can be very misleading as a predictor for the future.

It’s especially dangerous for those who use feed this past data into a computer and overoptimize models based on the past when the future is likely to be different.

Algorithmic decision-making in markets is great, but it can be disastrous when:

a) the data fed in and models derived from it aren’t representative of the future and

b) when the relationships that govern the underlying mechanics of financial markets aren’t well understood.

Inflation and central bank tightening

Traders are used to periods of low inflation/disinflation and central bank tightening cycles are becoming increasingly shallow as debt buildup prevents interest rates from rising significantly.

Central banks can create money and change borrowing and lending incentives but they can’t distribute money. They can only work through interest rates and a select few financial asset markets (US Treasuries, agency mortgage-backed securities, and sometimes corporate credit and ETFs during emergencies).

Fiscal policymakers can’t create money but they can direct where money and credit go.

When you combine these powers – i.e., the combination of the money creation capacity of central banks and the ability for fiscal policymakers to distribute it – it led to lots of money and credit going into the real economy.

All of this demand in excess of supply led to a rise in the prices of goods and services.

Geopolitical forces

After the inflationary forces were well underway, Russia invaded Ukraine, which compounded existing inflationary pressures and added a new level of risk.

Geopolitical changes followed to reorient the post-war economic order in major ways.

This impacted money and credit flows and it’s important to understand how the supply of assets and the supply of goods and services are impacted.

A war can exacerbate inflationary pressures because supply lines might be disrupted and countries might stop doing business with each other or significantly curtail their interactions.

So you can have a tremendous amount of inflationary pressure at the same time there’s already some level of stagflationary pressure as well.

This is because inflation in excess of a few percent on an annual level will be met with central banks trying to slow things down.

At a point, too much inflation is worse than economic weakness. Sometimes a recession is required to get things back on a healthy track.

So when money is coming out of the system as central banks tighten due to the inflation rates, governments will still want to accelerate their spending.

For example, with new geopolitical risks the US government is going to want to fund more military buildup and energy infrastructure that’s independent of Russia.

The supply of goods has also been impacted.

Some of this will be real growth because of the creation of new goods, but you also have commodity shortages, which is leading to more money being spent on commodities than other things.

This impacts financial assets because you have the impact of higher interest rates flowing into the economy and hitting the present values of asset prices.

Before there were any geopolitical tensions there was already a considerable risk of stagflation but that has only accelerated since.

Having a portfolio strategy for stagflation is vital.

The basic issue for central banks

The reason why we have recessions in terms of the basic business cycle dynamics is because the interest rate needed to control inflation is too high relative to what the markets and real economy can handle.

When central banks face a trade-off between too much inflation and too much economic weakness, they’ll generally try to straddle the middle as much as they can to try to hold out hope for a soft landing.

But eventually, they’ll overtighten and markets will fall, followed by the real economy. The financial economy leads the real economy.

How these issues impact the world

These issues are going through everywhere because of the effects on global commodity prices.

With supply chains, you have issues in countries that rely on Russia. And of course there are concentrated challenges in countries where Russian energy is a big deal, like Germany and a lot of Europe.

Russian supply chains are particularly relevant in certain types of chips and Japanese automotive parts and other places.

There was essentially a supply shock at the same time you need more spending. If you constrain supply and you have more demand, then prices go up.

The supply shock itself is stagflationary. In other words, you don’t get growth out of it but you get inflation.

But on the other side in terms of real growth, government deficits are going to go back up.

They have a new emergency, which is forcing them to engage in higher defense spending and more investment into domestic energy production.

At the same time, both governments and corporates have to rebuild supply chains and inventories.

The psychology of inventories

The psychology of inventories is similar to what they were back in the 1970s.

Because of inflationary pressure, companies and people are incentivized to hold more inventories to get ahead of price increases.

This is also a classic kind of behavior that causes inflation to become sticky. (Another one, for example, is when automatic price increases get placed into contracts.)

All of this is what’s commonly referred to as “inflation psychology”.

Inventories from the 1980s to the present have largely been seen as more or less costly and wasteful.

With all the investment decisions that can be made, most companies and people believe that buying stuff just to hold it for a long period isn’t a very good use of cash flow.

Building inventories is necessary.

Moreover, there’s also the recognition that your supply chain could go out at any time, which is leading to the need and desire to stockpile real goods.

This is a shift from a financialized economy to one where investing in the real economy becomes much more valued.

That has both a growth effect and an inflation effect.

If you take the supply shock, which leads to money getting taken out of the hands of consumers, but has the positive of more government spending (i.e., a near-term growth tailwind) and the rebuliding of infrastructure, this is not the kind of growth that’s wealth creating.

It’s simply rebuilding what was taken away.

Rebuilding inventory and rebuilding supply chains is simply recreating the level of the economy you had before.

It’ll count within GDP and provide an above-average figure in that respect because all those new goods and services are counted in it. But in terms of actual wealth creation, it’s really recasting what was lost in the first place.

Impacts on markets

The increased government spending is occurring at the same time demand is outstripping supply. This means the inflation and stagflation aspects will impact traditional stocks and bonds investments.

The impact from monetary tightening and higher inflation increases discount rates and eats into real returns.

There’s a liquidity hole that can open up from this because you have:

a) the increased government funding and larger deficits at the same time there’s…

b) central bank funding of these deficits being pulled back.

The Fed is unlikely to go back to QE policies until inflation falls significantly.

This lack of liquidity is a headwind on all financial assets. The real economy is absorbing a lot of liquidity and less of it is going into the financial economy.

And this is important in terms of what it means for asset allocation.

Diversification

Diversification is an important element in how to navigate these paradigm shifts in markets.

How you get diversification in this new type of paradigm is incredibly important.

Over the past four decades-plus, because of falling interest rates and easy Fed policies, the US was more or less the place to be.

Owning US stocks or owning a US stock and bond mix (such as the classic 60/40 portfolio) has performed exceptionally well.

But extrapolation of that trend probably isn’t very prudent.

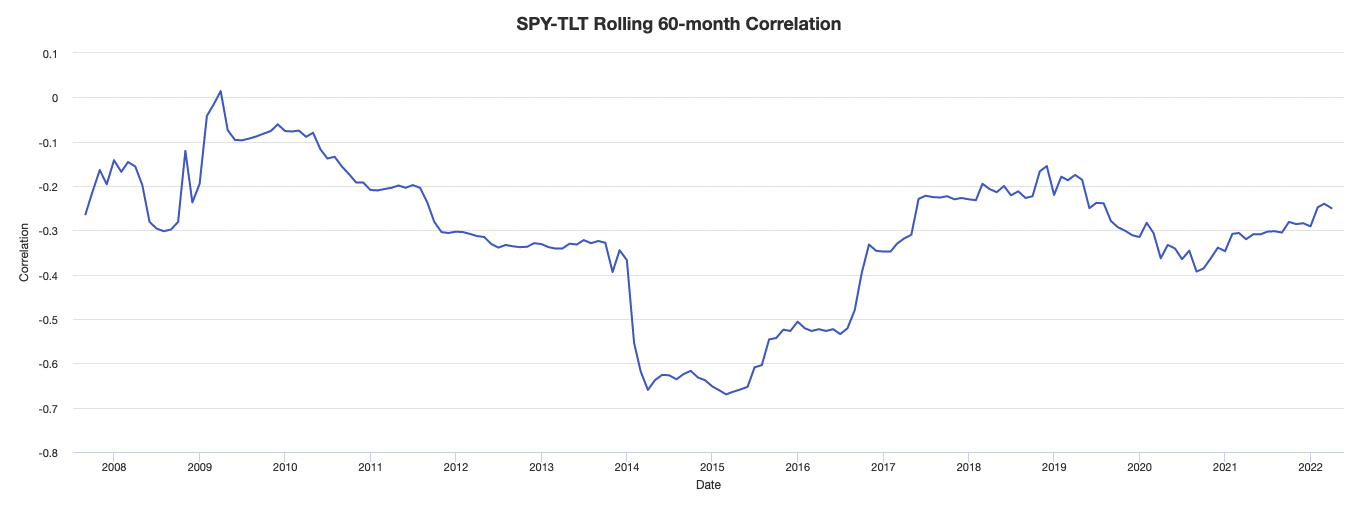

Moreover, previous correlation trends aren’t likely to hold up.

Stocks-bonds have traditionally been thought of as negatively correlated. But when bond yields get very low (around zero or even below zero) they can’t get much lower, so they no longer provide the same diversification benefit.

In more recent times, the negative correlation has been less pronounced (based on the SPY-TLT correlation, ETFs of stocks and bonds, respectively.

In places where yields are higher, it’s a different story, such as parts of emerging Asia.

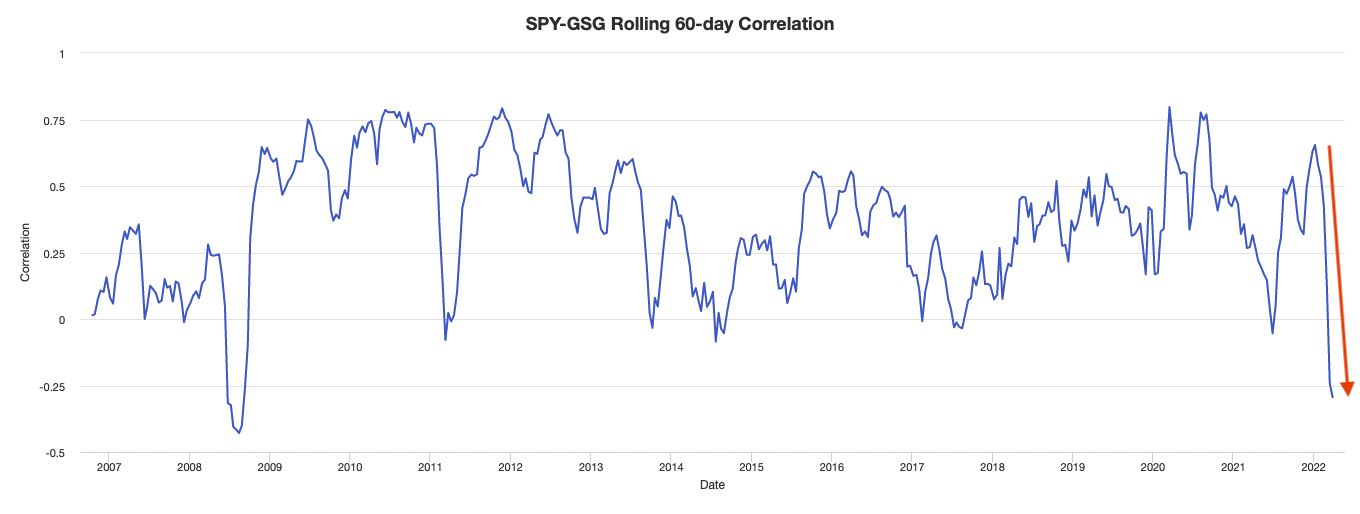

Equities and commodities have also traditionally been positively correlated.

But when there’s a supply shock, that’s often bullish to very bullish for commodities and can be a drag on stocks.

But with new geopolitical conflicts, this correlation went very negative (based on the SPY-GSG correlation, ETFs of stocks and commodities, respectively).

Correlations looking backward are fleeting byproducts of the environments that we’re in. Accordingly, they’re not reliable and basically the worst measure of correlations (compared to understanding whether things are intrinsically different from each other).

While equities and commodities have kind of seemed like the same theme over the previous decades – they both tend to do well in a rising growth environment – they are inherently different and can provide a quality form of diversification in a portfolio.

Looking backward, commodities haven’t been a great investment, but the risk today is a risk that’s always existed.

There are environments where commodities can be extremely valuable in a portfolio and provide a strong source of diversification to equities.

Getting around some of the inflation issue can be something like switching from nominal rate bonds to inflation-linked bonds such as TIPS.

And you don’t want to be in just one country, but diversify among many.

So understanding what assets help diversify a portfolio in these environments is an important question.

Monetary policy: 1970s vs. today

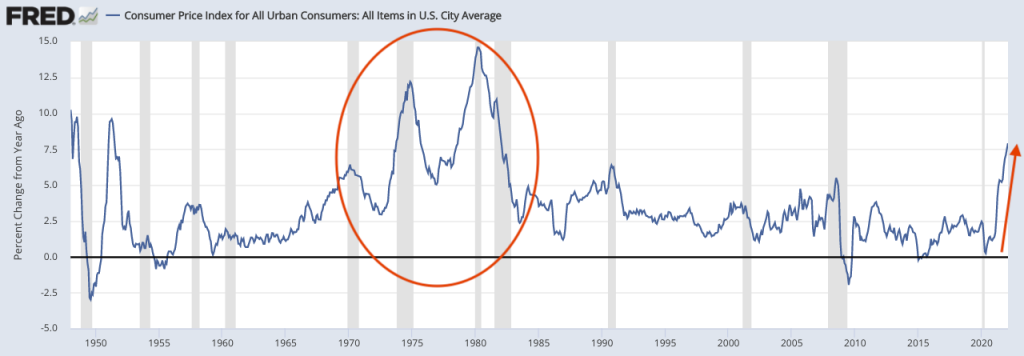

Looking back in the 1970s you saw big inflationary pressures for a decade.

So, it’s easy to say in retrospect that they should have tightened more during that period so they had avoided it.

Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in US City Average

(Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

But they were also balancing lots of different considerations.

Fast forwarding in time, the situation is largely similar.

The Fed is more behind than they were even in the 1970s in terms of where rates are relative to where inflation is running.

But there are also lots of pressures not to tighten too quickly, with geopolitical risks and the interest rate needed to get inflation back in line is much too high relative to what the economy can tolerate.

For example, if the Fed and other central banks encountering inflationary problems tightens to get real output at around zero, is that enough to get inflation back down to target levels (somewhere around 2 to 3 percent)?

There’s also political pressure not to tighten.

Plus, inflation has a demand component and a supply component.

The Fed and central banks can control demand (money and credit) but they have little influence over supply.

Does the Fed really want to tighten into a supply shock or an oil shock?

Tightening policy into an oil shock isn’t going to produce more oil and fix anything. In fact, it largely makes things worse.

And for many years, the Fed had trouble generating much inflation. So it’s been a purposeful policy to try to generate more inflation to avoid deflation, disinflation, and the stagnant wages of all of these challenges.

Now the world is no longer as deflationary as it was and policymakers know how to deal with deflation in terms of coordinating their policies with fiscal policymakers to generate more inflation.

And now the problem is the inflation sticking. The inflation is likely to stick as people’s investment and non-investment behaviors change in combination with continued easy policy.

So it’s understandable why the Fed is slow and will keep being slow.

Even before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the inflation issue was a matter of demand running above supply. Then a supply shock from this geopolitical conflict added further uncertainty around inflation and more hesitancy to remove the easiness around policy.

Under these circumstances, central banks will tighten but they’ll do so in a way that lags the inflationary pressures.

The oil shock factor

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the biggest upheaval for commodity markets since 1973. But the comparison to 1973 ends there.

Other than this being a Europe-centered shock, the other major way this crisis is different from the 1973 oil embargo is that this isn’t only a shock to oil supply.

It’s a shock to every single commodity: oil, gas, grains and food, metals, palladium, titanium, neon, and others.

Another big difference is that 1973 was a seller-driven boycott. This is a buyer-driven boycott.

Apart from the actual war, you also have an economic conflict in the sense that you have a decoupling between Russia and the West.

The actual physical decoupling – which will be seen all over commodity space – is still in the early stages. We have seen the boycotts but the actual transition to do this is going to be a very painful process and will be hard to physically achieve.

Along with the physical decoupling, the financial decoupling is starting to impact commodity markets, as well.

There was a sharp fall in the prices of many emerging market and Russian assets, which left a lot of market participants with large margin calls.

To fund these, they had to take profit on the only positions that were broadly profitable: commodities.

This only enhanced the volatility present in commodity markets.

Where currencies fit in all of this

Most notice what their stocks and other assets are doing but few pay attention to currency risk.

Gold standards, currency pegging, dollarization, currency boards

Currencies generally operate where they have hard backings, such as being pegged to gold or pegged to another more established currency.

Sometimes this might entail dollarization. This is when a country goes on the dollar even though they can’t produce dollars (because only the Fed can do that) and therefore don’t have monetary autonomy to produce more or less money in light of their own conditions.

This often takes place after their own currency was ruined, commonly due to high inflation that eroded trust. Dollarized economies include Ecuador and Panama.

A currency board is a more aggressive form of a pegged exchange rate. Management of the exchange rate and the money supply are not done by the nation’s central bank, if it has a central monetary authority. In addition to a pegged exchange rate, a currency board is also generally required to maintain reserves of the underlying foreign currency.

The flaws with hard backings

Because these interfere with the ability to have an independent monetary policy and the ability to create money and credit.

But they are eventually severed when some type of credit problem emerges that forces them to come off that peg.

This creates a devaluation relative to all sorts of different assets, such as stocks, commodities, and gold.

Fiat systems

The fiat system eventually works up to a point, moving interest rates up and down to balance out the supply and demand of credit.

But it leads to over-indebtedness and more money printing to cover it.

This also tends to come at a point where there have been too many other types of promises made that can’t be kept because hard currency flows aren’t sufficient (from taxes or other sources of revenue).

Easing too much creates negative real interest rates. This means wealth erodes holding the cash and credit denominated in the currency.

This eventually forces countries to bring back faith in the currency one way or another.

For the US during the 1970s, this meant pushing real interest rates to very high levels.

For others, it means spending discipline or a re-pegging of the currency to another reserve currency or to gold.

These cycles generally occur over several decades. Reserve currency regimes can last for more than a century.

So the arc is much longer than a typical business cycle, which is often 5-10 years, so we’re not as accustomed to them.

In 1971, the Bretton-Woods gold peg (established in 1944 as it appeared the US was on its way to winning World War II) was severed and that peg was really only re-established about a decade later by extremely high real interest rates.

Today, that’s still likely true, where higher real interest rates will likely be needed to essentially restabilize inflation expectations.

It’s also possible that that’s too difficult to do from a markets and economic weakness perspective and the dollar starts to lose credibility over time.

Holding the dollar as a reserve asset globally

At the same time, it’s also becoming more dangerous for various other countries to hold the dollar as a reserve asset.

For one, the yield on it is bad and the US’ bad finances (spend more than they earn and liabilities above assets) require lots more money creation to fund them.

And two, there’s more geopolitical conflict so being dragged into the dollar system can be painful if sanctions are ever levied for whatever reason.

So they have to learn to be independent of the dollar. At the same time, this also creates more inflation risk if there are less savings in the dollar and it becomes less of a reserve asset.

So if currency credibility is a key focus, they’re going to need to peg the dollar through a re-rating in real interest rates.

This, in turn, is going to require a different type of monetary policy than the one being run currently.

One that’s much tighter and one that would be painful for the economy and socially and politically unpopular. Nonethless, we’re still a way’s away from a “Volcker moment”.

For traders and investors, this means that holding dollars (stocks, bonds, and cash denominated in US dollars) in a concentrated way can be dangerous.

What are the alternatives?

Alternatives can include things like some commodities and gold. These are things that are hard, tangible, and non-financialized assets. It gives you something that’s not just paper wealth, or a financial claim on some type of income stream.

Inflation protection can partially come in the form of inflation-indexed bonds.

Geographic diversification is a key element.

And this is challenging too, because there’s not just economic risk but also the political risk of where you’re allowed to hold assets.

These will help you be balanced beyond just the classic stocks and nominal bonds mix, which can diversify relatively well with respect to growth. But stagflation can be a real killer to this type of portfolio. The commodities, gold, and tangible assets can help diversify with respect to this.

The main thing is – do you have a portfolio that could help you survive periods like the 1929 to 1945 period?

An 89 percent drop in stocks from peak to trough seems crazy, but everyone’s favorite asset class is going to drop at least 50 percent over the course of their lifetimes.

Stocks do horribly during periods of recession, but other assets kick in, such as safe bonds and potentially gold and other assets.

In the 1930s, you had a debt crisis, followed by various types of new conflicts between countries (trade, technology, capital, economics, military).

You had sanctions on different countries and various markets that closed and stay closed for years. This locked people out of their money entirely.

And do you have a portfolio that can survive the inflationary 1970s where you had monetary policy that was too easy relative to the conditions and falling behind inflation?

And of course other crashes like 2000, 2008, 2020, some of the market gyrations in 2022, and so on.

Traders and investors tend to know how to survive the periods they’ve experienced. This is because they know what happened and can backtest allocations that can get through these periods.

But they may not be able to effectively navigate the periods they haven’t experienced. Yet they are still those that come in a cyclical way over longer periods of time, such as wars and inflationary periods.

The dollar’s role and the weaponization of finance

We’ve had obviously greater periods of conflict in the past. But the main difference is that we’ve never had a global currency that’s been so powerful in such a financially globalized world as the US dollar is today.

Back in the 1930s the tensions were greater, but the dollar wasn’t nearly as central as it was today nor was the British pound.

The moral of the story for all countries is that you can’t be in a strategic competition with a country in which you save in their currency because they’ll always win that battle.

They have the capacity to print money – produce nominal wealth – faster than you can and they can hold that wealth hostage.

China and Russia are coming along to this.

And even before that, Russia had been moving reserves out of dollars and more into gold, Chinese renminbi, and others to reshuffle out of US assets.

And these disentanglements are coming in different financial systems with different technological systems in different spheres of influence.

The US is going to have its own sphere of influence, as will China, and the allies of each will be integrated while presiding over their own.

It’s also a big deal because the idea that savings are going to flow automatically into the dollar is now over.

This has implications for the dollar’s reserve status, which enables the enormous buying and borrowing power of the federal government.

In other articles, we looked at the history of the past several hundreds years and the arcs of the Dutch, British, and American empires and how that impacted their currencies and asset markets.

Changes in currency regimes are often caused by wars and changed in economic power.

This will eventually, in the long term, involve the dollar declining.

But the dollar won’t be eliminated as the central currency. It will become just one sphere of influence among more than one.

China’s role in asset allocation

China’s stock market suffered with the Russia-Ukraine invasion, as traders and market participants factored in that what’s happening with Russia could easily happen to China as well.

Ukraine to Russia is analogous to Taiwan to China and is a delicate point geopolitically.

China can be a diversifying return stream to at least passively consider, assuming you don’t want to put all your eggs into just one basket.

The risk of US and other international investors holding Chinese assets is discounted into markets to some extent. Is it sufficiently discounted?

Having some amount of China could make sense if it’s in a reasonable allocation. For example, having some 10 to 15 percent of a portfolio in a mix of emerging Asian assets could be appropriate.

There’s always the risk that you won’t be able to hold it, but there are also benefits to holding different countries.

For example, policymakers in China and emerging Asia are less constrained than they are in the west.

They don’t have the inflation issues, their growth rates are higher, and they have more room to ease monetary and fiscal policy, if necessary.

Holding US and European assets are also risky, but risky in a different way.

Even though the equity market hasn’t done that well looking at the aggregate returns over the past several years, a balanced portfolio also containing bonds and commodities denominated in local Chinese currency (RMB / CNY) has done well, with those assets working as designed in offsetting equity risk.

The risk premiums in holding Chinese assets are quite high given the risk surrounding them, but diversification appropriately sized is probably better than not having it at all.

The importance of looking ahead, not backward

Most market participants operate in a way where see what’s right in front of them and don’t do an adequate enough job of seeing what the next 2+ years will look like.

As a result, they tend to overemphasize asset classes that have done well in the recent past.

And lots of trading systems are built this way. These days it’s very easy to feed data into a computer and get highly optimized portfolios that do well looking at recent data but haven’t been well stress-tested throughout time.

When the future is different from the past, these over-optimized portfolios will have a problem.

For example, from 1981 to 2021, inflation hadn’t been a problem in the US.

As a result, this meant portfolios that help stocks and bonds largely did well with the tailwinds of falling inflation and falling interest rates.

This led to lots of portfolios being stuffed with stocks and bonds, such as 60/40 and other equity-centric approaches.

Then things changed in 2021 and stocks and bonds fell together in 2022 and it was a “big surprise” just because something happened that hadn’t happened recently but has happened many times throughout history.

Interest rates came off very low levels due to the rise in inflation. And because interest rates were zero or negative in many developed markets, this lengthened the duration of financial assets.

In turn, this set up asset prices for a sizable fall if interest rates did pick up materially.

Conclusion

The world is likely to be different from what most traders are used to, making an extrapolation from the past several decades probably a bad way to approach asset allocation.

Traders and investors will need to look beyond just US stocks and bonds, or beyond US stocks only.

Having assets like:

- commodities

- gold

- inflation-indexed bonds (e.g., TIPS)

- real assets

- emerging market assets…

…can be valuable rather than being concentrated.

Emerging market assets carry risk (like all financial assets). They have more political risk and their currencies aren’t as stable or as valued as reserve currency like the dollar, euro, yen, and pound.

The most commonly talked about emerging market is China simply because it’s the second-largest economy and has the second-largest capital markets globally.

There are concerns about whether Chinese assets are worth owning (especially in light of the Russia situation) in light of not just economic risk, but political risk?

But including Chinese assets in a diversified portfolio can make sense up to a certain percentage.

As a trader, you have to ask yourself whether having that diversification (say 10-15 percent of your portfolio in emerging Asia) is worth having or would you rather have nothing and make more concentrated bets on developed markets?

The global financial markets are in a state of flux as we move into a new era where the US is no longer the undisputed global power. This paradigm shift has consequences for assets, countries, and currencies.

Naturally, there is a wide distribution of outcomes. The way the world is now is just one roll of the dice out of which many outcomes were possible.

Ideally, a well-structured portfolio will account for these unknowns and try to be immune from what’s unknown and what can’t be known.