War Economy: What Assets Should I Own During a War?

Financial markets come with lots of risks. Whether it’s debt crises or acts of nature, wars, and other events, traders are always thrown curveballs in one way or another.

Many of these things come as a surprise because they haven’t happened during the time we’ve been trading and investing in the markets or because they haven’t happened in our lifetimes at all.

This is where a study of history can be valuable to ensure that what’s happening before us doesn’t take us by surprise.

In many ways, the current period is analogous to the 1929-1945 period, where we had:

- a downturn in the economy

- interest rates hit zero and central banks printed money, and

- lots of internal and external conflict followed in a variety of ways throughout the 1930s until…

- …the outbreak of a hot war in 1939, which expanded into an all-out global war between the major superpowers in the 1940s

We’ve written about these issues in previous articles:

i) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

ii) technology

iii) geopolitical

iv) military

Based on what we’ve been seeing, the US and China are clearly in four types of competitions and conflicts – trade and economics, capital, technology and geopolitical.

These conflicts are not intensely hostile, but they will get hotter as time goes on.

Russia got into a hot war with Ukraine in February 2022, though this has yet to expand globally.

We can see from previous cases in history, in particular the 1929-1945 period, that these four types of conflicts come before military wars by around 5 to 10 years. The risks of military war beyond Eastern Europe seem relatively low, but they’re increasing.

We’ll go through some current considerations as well as how to trade and invest in a war economy, including what types of assets are best to own during these periods.

The overall cycle

When you get to the latter stages of the credit, money, and capital markets cycles, there is naturally more conflict.

We hit that point in 2008 from a debt crisis in the developed world, like in 1929.

To “save the system” governments respond by printing money and handing out a bunch of credit, which causes investment assets to go up when all this money and credit is spent.

This process benefits the rich disproportionately to the poor because the latter group largely doesn’t own stocks, real estate, and so on. So they tend to be left behind and this makes a lot of people angry and convinced that the system is unfair.

Wealth gaps increase, which increases social frictions between the left and right, rich and poor, ethnic groups, etc., and these conflicts become especially bad when there’s an economic downturn.

These social frictions bleed into political movements, so you tend to see more populist leaders get elected to office. Populism becomes more popular.

These developments often precede international conflict. For example, 1929 was the classic downturn preceding World War II.

The 1930s were a period of greater external conflict, as some powers rise and fall in absolute and relative terms as a result of these shifts.

Trade relations are the first domino to fall and you have other conflicts with respect to economics and capital (currency, debt, capital markets), technology, geopolitical, and military armament.

It manifested in a global war by the late-30s and early-40s.

We’re also on an analogous track now, but warfare has become so advanced that the doctrine of “mutually assured destruction” will make world leaders more careful about starting broader wars.

Negotiating vs. Aggravating

As time goes on, hopefully both sides will have the incentive to negotiate rather than get into a military war.

World War I – then called the Great War – was the most destructive war that had ever occurred by that point in time with 15-22 million deaths and around 20 million wounded.

Then, 25-30 years later, World War II was even bloodier because the capacity to inflict harm had advanced so rapidly, with an estimated 60 million deaths and 25 million wounded in battle.

Now, many more decades have gone by since the last World War. And with that, the ability to inflict harm has gone up even exponentially more since nuclear weapons were developed and used to end World War II.

Nuclear and conventional forces are bad enough when it comes to the thought of war.

Now you throw in the additional elements of warfare that are largely unknown and heavily untested in many ways – e.g., biological, chemical, space, cyber, and other forms of warfare – including the different types of weapons systems within the various categories.

Then you can imagine both sides – the US and its allies (most notably the NATO countries) and China and its allies (most notably Russia, an important nuclear power) – turning the pain dial up all the way.

Accordingly, it’s hard to imagine who would win a broader war because so much is unknown.

Even the leaders who are most informed on both sides have much that they don’t know because a lot is unknown and can’t be known, and because hot wars always play out in ways that can’t be known.

“Mutually assured destruction”

Many know that the doctrine of mutually assured destruction prevented the US and the USSR from entering a military war before the Soviet Union fell. The collapse of the Soviet Union was mostly due to the failure of the various regimes to grow their other strengths in the face of big military spending.

China is roughly comparable in power to the United States in the most important ways, and it is on its way to becoming more powerful in many ways.

China has more than 4x the population of the United States and they produce roughly 6x more STEM graduates than the US.

So even if China were to produce a GDP per capita of half that of the United States, it would be more than twice as big economically.

China won’t be as easy to defeat in any of the five types of conflicts or wars as the Soviet Union was, and the USSR wasn’t easy to defeat.

That means the wars are likely to intensify and increasingly favor China, especially if the US doesn’t turn around the other fundamental underpinnings of strength that it’s losing.

At the same time, it seems like it will be a long time before China can win a war without having the war lead to its own destruction as well.

Small wars turning into big wars

History has shown that small wars can advance beyond anyone’s control and turn into much larger, intensely destructive wars.

These wars are always much more intense than even the leaders who chose this path imagined they would get; so, virtually all parties involved wish that they chose the “first path” of diplomacy – i.e., tough negotiations done with mutual respect and consideration.

Either side can force the “second path” (e.g., military war) on the other. However, it takes both sides to mutually follow the first path.

In the case of all parties involved, regardless of whether they choose diplomacy or war, top of mind should be their relative powers.

The weaker power is most interested in falling into the subordinate position without fighting.

But there’s usually something or multiple events along the way where they’re after power or they’re wronged in some way by a foreign power so they end up fighting. Or they believe they have an ally they can rely on, so they fight even though they’re weak in other ways and fighting alone would be illogical.

For example, Russia is strong militarily. But it is not strong economically, technologically, or geopolitically, and it doesn’t have overly attractive capital markets – i.e., it’s not seen as a safe place to invest money and it doesn’t have reserve currency status.

So Russia’s actions toward Ukraine don’t appear to be logical unless it has an ally who is strong in those ways, which is most obviously China.

Moreover, Russia can’t know for certain how its actions will affect other players around the world, most notably the various NATO countries – a military alliance that dates back to the post-WWII restructuring, containing mostly European countries along with Canada and the United States.

Russia is stronger than Ukraine on its own (and it’s not easy for Russia to defeat Ukraine on its own).

But Russia’s relative strength is not clear if NATO countries and/or the US is involved.

Diplomacy vs. war

In the first case, the parties should realize what the other could force on them and appreciate the quality of the exchanges and interactions without getting too aggressive.

In the second case, the parties should realize that power will be defined by the relative abilities to endure the other side’s attacks as much as the relative abilities to inflict it.

When it isn’t clear exactly how much power either side has to reward and punish the other, the first path is the safest because there are lots of unknowns over how each side can hurt the other, whether that’s conventional forces, nuclear, or otherwise.

On the other hand, the second path will certainly make clear which party is dominant and which one will have to be submissive after the war is over.

That holds both within countries and between them. When parties cooperate and compete well, and don’t waste resources on fighting, productivity and living standards rise.

When they fight, they waste resources (sometimes including lives), they destroy more than they produce, and living standards fall.

The worst decision a leader can make is getting involved in a war that it loses.

As a result, wise leaders typically only go into military wars if there’s no other choice because the other side coerces them into the position of either fighting or losing if it were to back down.

The US and China

The US and China are the top obvious superpowers in the current world order.

China and the US will be powerful enough to inflict unacceptable harm on each other in a variety of different ways.

So the prospect of mutually assured destruction should prevent a hot war. But there will almost certainly be challenges and dangerous confrontations.

Moreover, as time passes the risks increase.

If the US continues to decline in relative power for its various reasons and China continues to rise, what’s most important is whether each is able to do so knowing their relative powers and without the fighting and losses (in terms of lives and money) that would come out of it.

The big risk is when there are irreconcilable differences exist and there is no mutually agreed-upon intermediary, party, or process to adjudicate and resolve the conflict, there’s an increased chance that there will be a military war.

Taiwan

Russia’s position on Ukraine is analogous in many ways to China’s position on Taiwan.

Taiwan is a unique interest for China and there is evidence and widespread belief that China would fight for the island nation 90 miles off its shores because of its belief that “there’s one China and Taiwan is part of China.”

Would the US consider Taiwan worth defending in a major battle over the island?

It’s uncertain whether the US would want to get involved and Chinese military experts believe the force China would use would try to overwhelm any defense – i.e., Taiwan’s and before allies could try to step in, if they were willing.

It’s still worth watching as Taiwan stands as the major trigger for a military war between the two greatest powers in the short-term.

A clash of cultural differences

What the US and China fundamentally have is a clash of cultures. Their differences are at the forefront of much of the conflict.

Most Americans look at these differences through the lens of simple stereotypes that are painted for them by biased parties (“that’s what communists do”).

US policymakers should accept that they’ll run their government and economy via monetary and fiscal policies in the ways that they believe are best suited for them and seek to understand those ways better.

China’s economic results have been extremely impressive over the past few decades, so we shouldn’t expect them to abandon their approach for the American way and we should study their approach to see what we can learn from it, in the same way the Chinese have studied and learned from ours.

Most of the conflict boils down to a competition of different approaches. Presumably, what we want most is to follow the best approach.

In China, the word “country” consists of two characters, “state” and “family.” This essentially represents how the leaders view their roles in looking after their state, analogous to how parents might look after a family.

So one might say that the Chinese government is run in a way that is considered more “top down” – like how the family unit is run – and optimizes for the whole.

On the other hand, the American approach is run from the “bottom up” (e.g., a democracy where everyone has an equal vote in electoral outcomes) and optimizes for the individual.

These differences of approach can lead to policies that those on the opposite side find objectionable.

For example, the Chinese government regulates what types of books, video games, movies, and other forms of entertainment its people are allowed to consume.

In the United States and developed Europe, we might find such policies to be an overreach of government and believe these decisions to be best left to the individual.

Should we worry?

If people worry because they study history and understand what is happening in the present, they will be better equipped to make sure the bad outcomes won’t happen to ensure a continuation of the good times.

A common element of the rise and fall of various countries and empires is that those who experienced financial hardship in the early stages of a rising power rarely lose their financial cautiousness.

However, if countries develop to be rich, the younger generations lose sight of the bad times because the good times are all they’ve ever experienced.

So they’re more likely to go into debt and make riskier investments and financial decisions than previous generations were.

For example, many who lived through the Great Depression in the 1930s and the war years of the 1940s were afraid to invest in stocks. This is because of their experiences seeing the precipitous falls and excruciating bear markets equities went through and how it led to the ruin of many traders and investors.

Nowadays, their grandchildren and great-grandchildren have no second thoughts of pouring all of their savings into extremely speculative stocks and cryptocurrencies that carry many multiples of the risk of investing in standard stock indices.

Likewise, in the classic peace-war cycle, the old generation who has been through wars and remembers the horrors of them has died away. And the existing generation is more prone to take on risk and fight rather than negotiate a path forward that both sides can accept and abide by.

The 3 Most Important Factors Guiding the Future

By and large, there are three big factors going on right now that will impact how the future will be different from the present:

Financial

The US and most reserve currency countries are spending more money than they’re earning – and in some cases, significantly so – and have more liabilities than assets.

They are attending to these issues in the classic way of monetizing these shortfalls by “printing money” which is likely to decrease in value.

Internal conflict

The internal conflict refers to fights over wealth and power, what values are most important, and how people behave with other (cooperative or combative).

Usually, there is a fight over power. The winner has a proclivity to pursue policies that are left-leaning or right-leaning.

Fights then ensue between the factions, which can be violent or non-violent.

In cases where the partisanship becomes extremely bad and working together becomes impossible, the odds of some type of civil war can become likely.

In the US, rule of law and respect for rule of law is common, so the odds of some type of a civil war in the US may be less relative to where they might be in cases where respect for the constitution is less.

Odds of these conflicts increase during the most pivotal election years (i.e., when there is a presidential election, such as 2024, 2028, 2032, and so on).

External conflict

The external conflict refers to the competitions, conflicts, and fights between powers that go on to determine the world order.

____

Resolution of these issues

Compromise and financial prudence are important, but that doesn’t always go according to plan.

Moreover, acts of nature can be very disruptive, such as floods, earthquakes, droughts, and plagues.

These natural events have wiped out more civilizations than military wars, civil wars, and economic disasters combined.

So even though they’re rarely considered they are important to take into account.

The effect of technology changes will matter in a big way as well. Whoever is technologically superior tends to be superior in most other ways, including economics and militarily.

So the technology competitions and the development of emerging technologies between powers are something to watch.

How does a war economy impact investment assets? How should I invest during a war?

Investment assets trade more heavily as a result of their cash flows and based on monetary policy – i.e., the action of central banks.

When wars do affect financial assets it’s because the wars (or consequences stemming from them – e.g., sanctions, war debts) affected those cash flows and what central bankers did.

Wars can wipe out financial wealth when a country is ruined by war. In other cases, financial assets are not impacted much.

But any world leader entering a war will realize that a war won’t go according to plan and it will be worse than they could have foreseen upon entering it.

Where are the best places to invest in a war economy?

By and large, the best investment assets to own are”

i) assets that can be moved across the world or accessible from anywhere, and/or

ii) assets that can’t be moved from place to place but are held in places that are safe and not vulnerable to being ruined, seized, devalued, etc.

For example, real estate is not portable but is often viewed as a safe investment in many top-tier cities in reserve-currency countries. New York/Manhattan is one place many people from all over the world will consider buying property; London is another.

In wars, the common tender is gold, silver, and barter.

Countries tend to not trust each other – especially those who are not allies – because they have reason to suspect that currencies will be devalued.

This is especially true as wars are significantly costly to fund, which comes with debt and money printing to fund them.

So, it is common in wars to buy gold and sell credit (bonds / debt assets).

Fiat currencies are someone else’s liability while gold is not.

Commodities are often high in demand as well. They can also serve as alternative currencies. They have intrinsic value.

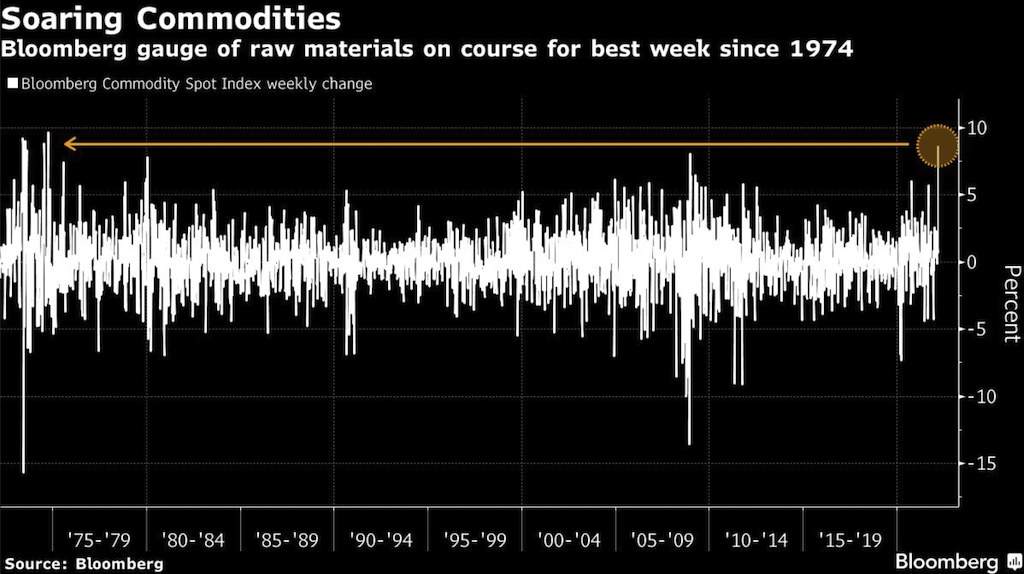

For example, when war broke out between Russia and Ukraine in February 2022, the commodities index had already had its single best week since 1974 just mid-way through the week.

This dash for commodities reflected existing deficits of a broad range of them, the increased industrial demand, and the desire to hold things that have intrinsic value.

The equities and credit markets of those who win a war often remain strong or untouched.

On the other hand, those who lose often see their stock and credit markets lose a lot. In some cases, all financial wealth is wiped out, including the currency.

Currencies in a war economy

Countries develop foreign exchange reserves as a form of savings.

They can use these reserves as a type of rainy day fund.

During peace times, the value of these reserves is always assumed to be good. The top reserve currencies tend to have the largest representation in foreign reserve accounts.

As of now, the US is around a bit less than 60 percent of foreign currency reserves, followed by the euro at about 20 percent, with the yen and pound responsible for around 5 percent.

Others represented include the renminbi, Canadian dollar, Australian dollar, New Zealand dollar, Swiss franc, and bits and pieces of others.

However, during times of conflict, things become more complicated.

FX reserves commonly come in the form of debt (bonds). Countries can unilaterally decide to renege on their promises to deliver on these.

This is why gold has commonly been a popular reserve. While gold is imperfect, nobody has to worry about more of it being printed or it being the liability of another party who won’t make due on the promise to deliver it.

With fiat currencies, someone can decide to devalue them or not pay the debt denominated in that currency.

For example, in 2021, once Afghanistan went under control of the Taliban, the IMF suspended the country’s access to funds and Special Drawing Rights (SDR).

In another example, sanctions on Iran mean that holding USD reserves offshore doesn’t inhibit the US Treasury from taking action.

So if currency balances simply became numbers on a screen and weren’t backed up by actual fulfillment that could guarantee purchases of things, Russia would be wise to stop building up traditional forms of FX reserves – especially with countries it has geopolitical conflict with – and instead stockpile assets with intrinsic value.

This could be things like gold, oil, and other physical assets. It could also include more investment into Chinese assets.

Many countries have wanted to avoid buying up the Chinese renminbi based on fears that access to it could be easily revoked – there is an onshore and offshore market for the RMB (CNY) – unlike the dollar.

But this is true for all currencies.

Moreover, many countries are likely to shift away from US dollar reserves.

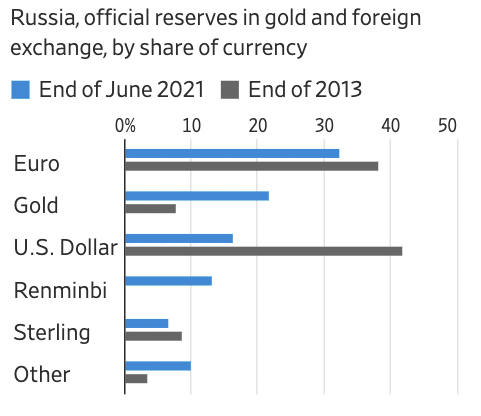

Russia has been steadily shifting its reserves away from USD and into gold and renminbi.

Dollar reserves went from more than 40 percent in 2013 to less than 20 percent in 2021. Euro reserves went down slightly.

(Source: WSJ, Bank of Russia)

Part of this is geopolitical conflict. Another part is basic financials.

If the US and Europe have zero interest rates and they’re creating a lot of new debt and money to fund these deficits, this makes dollar and euro currency and credit less attractive, supporting a shift into renminbi and “inverse money” assets like gold.

So far, the dollar’s reserve status hasn’t come under pressure despite the country’s financials.

Most countries are still aligned with the West and Beijing still has capital controls undermining the internationalization of its currency.

But China’s financial and economic ties to the rest of the world will strengthen. At some point, Beijing will no longer need to stringently tie up its capital account and will be more willing to free-float its currency.

Nations that are sanctioned by the United States will naturally want to accumulate more of these other reserves, including the renminbi and gold.

But even nations that aren’t sanctioned will want to diversify so they don’t have so much concentration risk and to diversify themselves geopolitically outside pure financial and economic considerations.

The currency matter is a further wedge that will emphasize deglobalization and the separation into a more bipolar world, economically, financially, geopolitically, and militarily.

What would happen to my money in the event of a war?

This is a multi-faceted topic that has multiple angles to it.

Banking

If there was a war, banking would go on as usual but they might seize the accounts of those from enemy countries.

For example, in 2022, lots of countries sanctioned various Russian “oligarchs” to try to prevent them from doing business.

Their bank accounts were frozen and they tried to seize their personal property (along with the assets of many of their relatives and/or close associates who have benefited from ties to the Kremlin and Vladimir Putin).

Capital controls

There are also cases where a country may impose capital controls to prevent money from leaving the country (what Russia did after it started war against Ukraine in 2022).

China allows its people to take only a limited amount of money out of the country each year, which results in various workaround approaches to get money out. That’s part of the reason why China doesn’t allow cryptocurrency and other alternative payments systems within its borders.

Inflation

Many countries also suffer from high inflation during war periods because they have high spending needs.

During World War II, the US kept interest rates artificially low to enable the government to borrow lots of money without having to pay a lot of interest on it.

So people may lose a lot of purchasing power on their cash and bonds.

Financial market closures

There have also been cases of financial market closures during war periods, which means people can be shut out from their money in stock and bond investments, potentially for years.

The US did so for four months during 1914 (WWI), but kept them open during WWII. Other countries had them shut for years.

Markets disappearing

Sometimes markets disappear entirely, typically associated with revolutions (e.g., Russia 1918, China 1949) and hyperinflation (e.g., Germany 1923).

Japan was a near-total wipeout (down 96 percent) from the Great Depression and WWII. Austria lost 95 percent from WWI and hyperinflation from losing the war. France lost 93 percent from the Great Depression and German occupation in the 1940s.

Takeaway

The takeaway is to ensure you have the basics secured and have good diversification among different assets, asset classes, countries, currencies, and financial and non-financial stores of value.