What Will Happen to the Ruble?

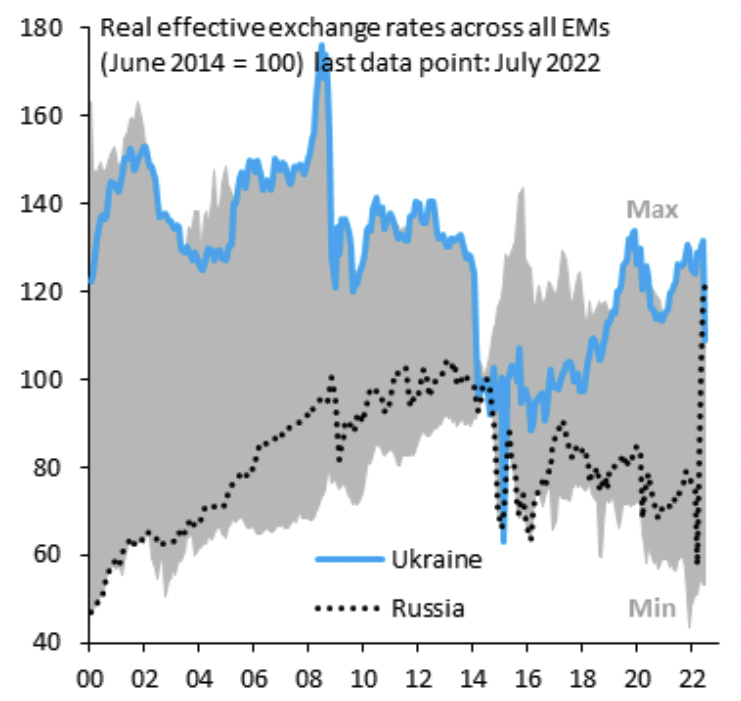

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and sanctions imposed by NATO countries and western allies put the Russian ruble (RUB) into a tailspin against virtually all other emerging market currencies.

The sanctions guarantee that Russia will have bad inflation problems.

Tightening monetary policy can help take some of the air out of inflationary pressure, with the trade-off being a deep contraction in credit creation and therefore a contraction in the economy.

What will determine the exact bottom in the ruble?

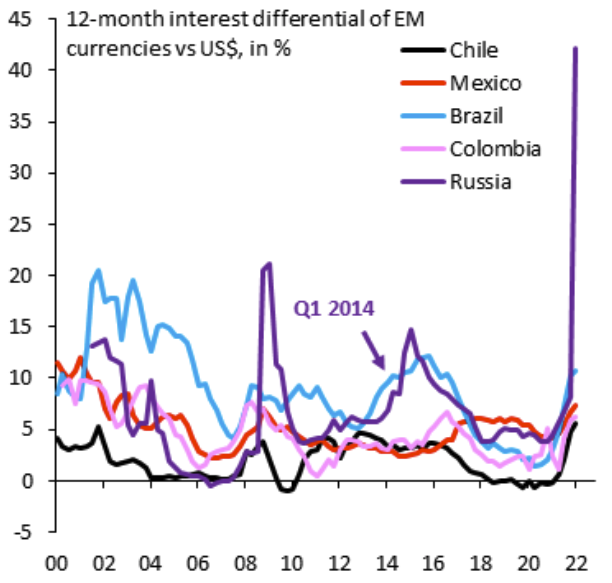

In emerging market currency crises, whether you’re looking at it from a pure economics perspective or for purposes of trading, you’re looking for the interest rate differential that will compensate for the depreciation in the value of the currency.

In the early stages of the invasion, the one-year interest rate differential in the currency forwards ballooned out to 42 percent. That’s far more than the ~15 percent or so that was associated with the 2014 Crimea annexation and more than the 2008 tightening.

(Source: IIF)

This is heavily recessionary as the 42 percent implied 12-month forward rate gives an indication of how much tightening needs to occur in order to bring equilibrium back to the currency.

An interest rate differential of 42 percent is extreme and no country’s economy is able to withstand that rate given it virtually guarantees a contraction in real economic growth.

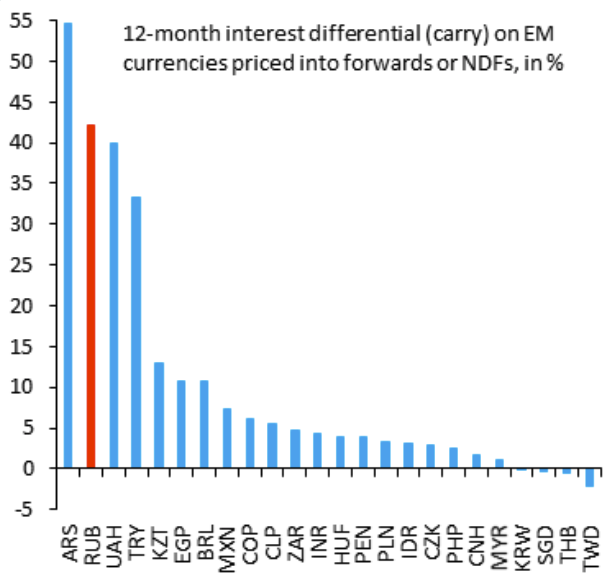

Before this, Argentina had been an outlier in global financial markets with its own set of economic problems, with a 12-month interest differential at 55 percent.

A rate of that height essentially implies exclusion from global capital flows. Due to the Ukraine invasion, Russia came into the same vicinity. Ukraine was taken down financially and economically with Russia and Turkey has traditionally had problems that have been analogous in ways to Argentina’s.

(Source: IIF)

How policymakers prevent the freefall of a currency

One way or another – sometimes through support from the IMF (which is out of the question for Russia, so long as the Putin regime is in power) or a tightening in monetary policy – the central bank will need to create an interest rate that will offset the combination of:

a) the inflation rate, and

b) the depreciation of the currency from the underlying capital flows

And knowing how that mechanically happens is the means by which you can identify the bottom in the currency.

Typically, countries undergoing currency crises have fiscal deficits.

And how they choose to monetize those deficits – through, e.g., external loans or funding, restructuring of their debts/liabilities, the tightening of monetary policy to attract capital flows – will be the determinant of the exact bottom in the currency.

Currency or interest rate pressure

Another important thing to consider is that the pressure in these situations can come from the currency side or the interest rate side.

A fall in a currency creates inflationary pressure. When the currency isn’t worth as much anymore, then it can’t buy as much as it used to, producing inflation. For example, imports from abroad will cost more and those costs will be passed off to consumers.

To control this, the central bank typically raises interest rates in what’s called a “currency defense.”

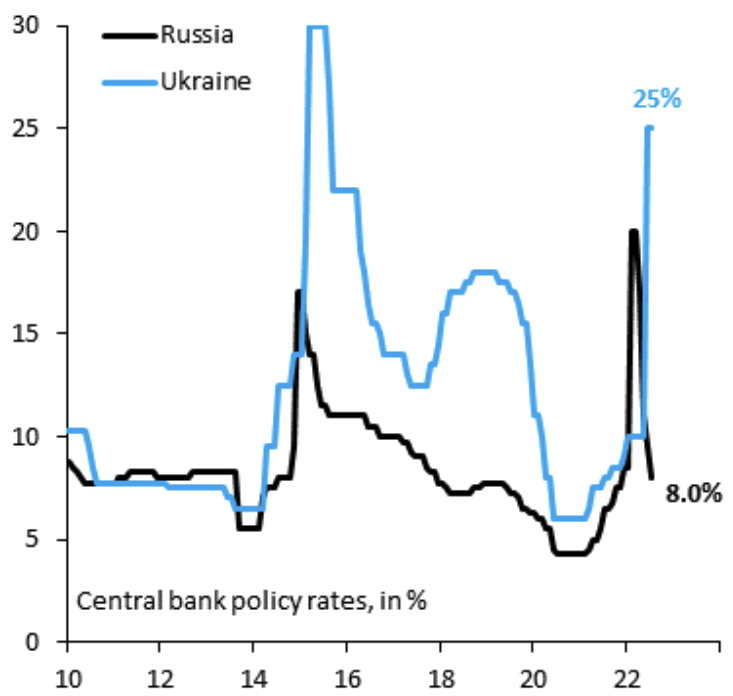

In the early stages of the fall in the ruble after the Ukraine invasion, the Bank of Russia raised its short-term interest rate from 9.5 percent to 20 percent.

This is the classic currency defense to try to get more savings into the currency to prevent a structural liquidity crisis.

In that case, any shorting of the ruble against another currency may have lost steam. However, in that case, shorting Russian interest rates or credit (or even equities) would have taken over as the winning trade.

The effect of sanctions on the ruble

The West imposed powerful sanctions on Russia and they are working.

But how effective these sanctions can be was undercut by rising oil prices, which will provide a large amount of hard currency inflow into Russia.

This windfall isn’t touched by sanctions. And it’s Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that drove oil prices higher.

How much do sanctions hurt Russia?

FX forwards provide some insight.

Capital flight and frenetic hedging activity caused the forwards to blow out to north of 40 percent against the dollar and price lots of depreciation in the ruble. But it’s still less than in 2015.

(Source: IIF)

Later it widened further to over 50 percent.

Russia crashed into financial autarky (i.e., the state of being almost totally independent and isolated).

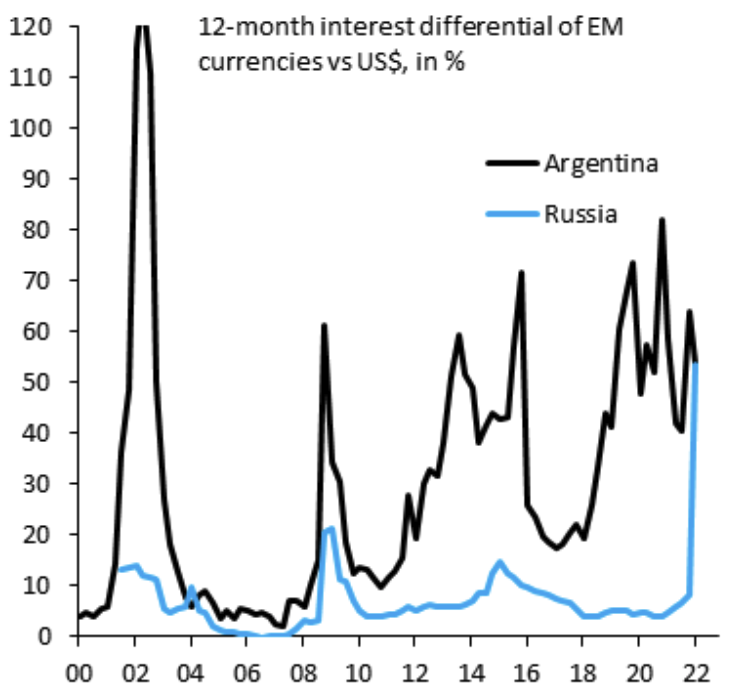

To observe just how extreme the crash was relative to other cases like Argentina, you can similarly compare the depreciation one-year forward as priced into the currency forwards for the Ruble (blue) vs the Argentinan peso (black) relative to a top reserve currency like the US dollar.

In both cases, markets priced over 50 percent depreciation, which is essentially total segmentation and heavy withdrawal from the rest of the world.

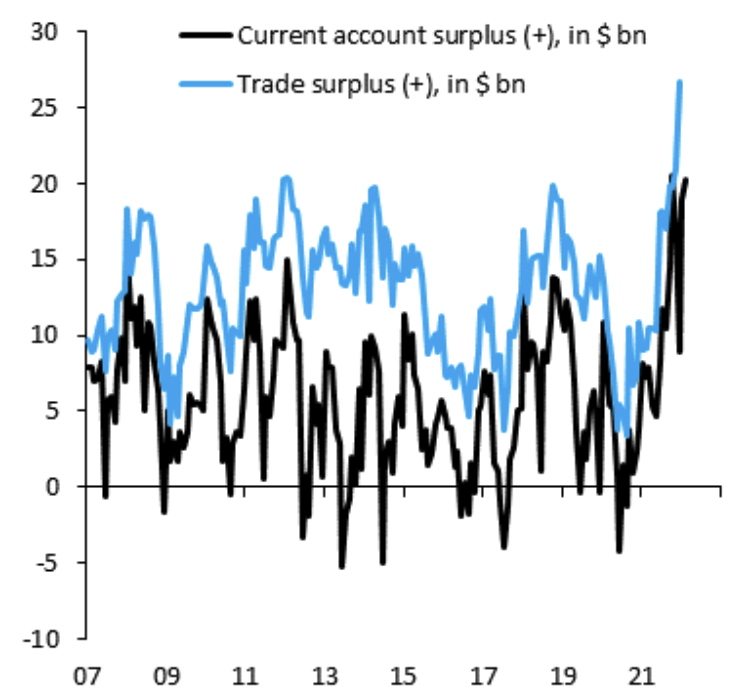

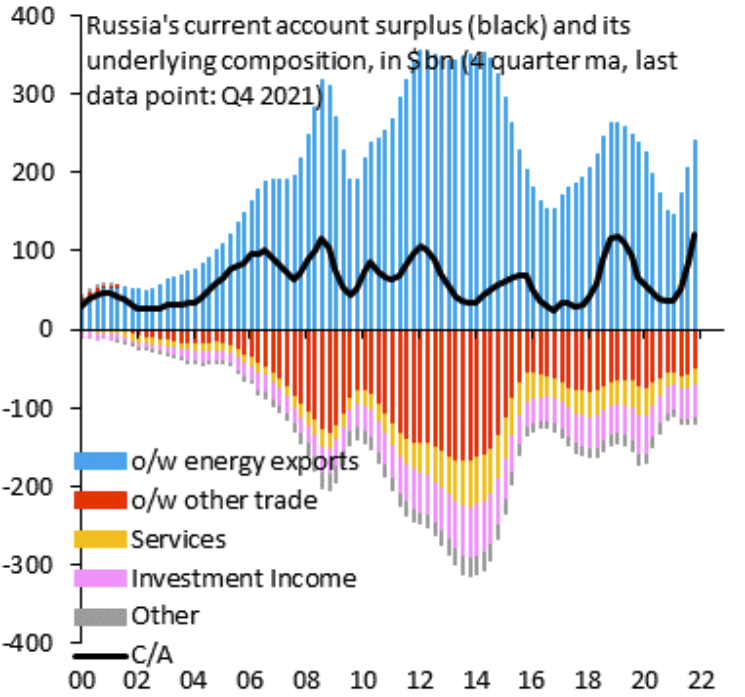

Russia’s current account surplus was larger than ever (red) just preceding the invasion that started on February 24, 2022.

(Source: IIF)

February 2022 data for Russia’s current account surplus (below, black line) found a surplus of +$20.2 billion. This reading is an “off the charts” relative to the same month in previous years, due to the rise in energy prices providing a hard currency windfall to Moscow.

The invasion effectively helped its current account surplus as it was (by leaps and bounds) the primary reason why energy prices continued flying higher.

That’s a significant amount of hard currency inflow that effectively sidesteps sanctions.

Only a boycott of Russian energy would fix that and political leaders are reluctant to do so.

They fear driving oil prices even higher if the West significantly or entirely cuts itself off from Russian oil and gas, stoking intolerable inflation while their economies are already struggling with it. Naturally, there are political risks associated with this.

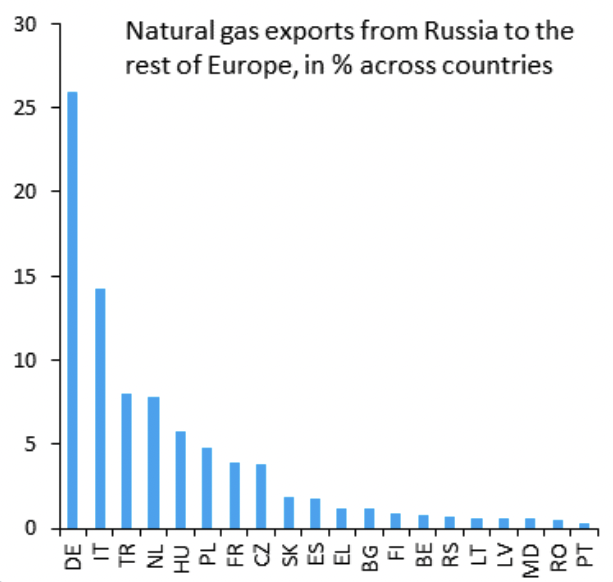

A small number of European countries consume the majority of Russia’s natural gas.

Based on 2020 data, the biggest consumers are: Germany (26%), Italy (14%), Netherlands (8%), Turkey (8%), Hungary (6%), and Poland (5%).

(Source: IIF)

Russian energy boycotts?

A big factor involves what a boycott of Russian energy would do.

Because Europe (especially Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands) is so dependent on Russian gas, it’s difficult to wean off these supplies.

However, Russia uses its sales of energy to finance the war. Every $10 rise in oil prices boosts Russia’s current account surplus by 1.5 percentage points of GDP.

Every other element of the current account (services, investment income, other trade, and so on) is in deficit.

Each $10 rise in oil is essentially equal to $20 billion of current account inflows per year. Despite around 40 percent of the $640 billion of the Bank of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves arrested, Russia could rebuild buffers from the current account surplus.

So boycotting Russian energy is a key cog in the economic arsenal.

Without that hard currency flow, Russia will be forced to print money to finance it. Russia has no reserve currency status, which is a major impediment. Not having the income from its energy sales will push the ruble into a devaluation spiral.

If Russia keeps printing money to keep up the war effort and isn’t able to close the gap from hard currency or external funding, it would need to choose between war and hyperinflation.

Sanctions limit Russia’s ability to use its foreign exchange reserves to smooth out economic shocks.

Boycotting Russian energy would be a huge shock, given energy exports (blue) pay for all imports (red).

Russia current account surplus and underlying composition

(Source: IIF)

Without FX reserves, imports collapse to zero, making it harder for Moscow to fight this war.

However, with Russian energy boycotts, Moscow continues to receive dollars and euros from countries that buy its oil, gas, and other commodities.

It then requires those receiving the money to convert 80 percent of it into rubles, which helps manufacture demand for the currency.

With energy paying for all imports and expenses, Russia can defend the ruble and won’t enter into a devaluation spiral.

Moreover, because of domestic recession, imports collapsed, and increased the current account surplus, further aiding the appreciation of the ruble after the initial fall.

Why embargoes can be effective

There’s a basic reason why an embargo would be so effective.

In instances like Russia where:

- the exchange rate falls by 20 percent or more relative to top reserve currencies (or gold)

- imports fall sharply (because they can afford less with the currency depreciation), while

- exports hold up the economy (which are more affordable)…

…net exports are the growth driver in a situation like this.

An oil, gas, and commodities embargo would hit the only growth driver that Russia has available.

So long as Russian energy is imported, Russia has a current account surplus and will accumulate foreign assets. If some banks are sanctioned like the central bank, foreign asset accumulation will shift to entities that are not sanctioned.

Sanctions on Russian banks and an energy embargo are tightly intertwined.

Assume all Russian banks are sanctioned. In this case, there would no longer be any way to pay Russia for oil and gas imports. Accordingly, the delivery of these commodities would stop.

Sanctioning all banks is the de facto equivalent of an energy boycott.

Moscow’s demand to be paid for oil and gas in rubles

Russia asserted it wanted to be paid for its gas in domestic currency.

What does that mean?

Russia is a current account surplus country, i.e., it exports more than it imports. Balance of payments surplus countries are taking in more than they spend on an international level, so they build financial claims on other countries.

That happens in one of two ways.

First, Russia’s central bank (the CBR) can buy the hard currency the current account surplus generates and sell rubles.

That reserve accumulation would count as an official capital outflow because it’s the central bank buying foreign assets.

But because the CBR is now sanctioned, this option is not available.

Second, a non-sanctioned “private” bank or financial institution can buy the hard currency and use it to invest abroad.

This is also a capital outflow, but it now goes via a private financial institution, not the central bank.

What sanctions have done is to migrate capital outflows from the CBR to private sector banks (which are quasi-private entities because not much is truly privatized in Russia).

So the current set of sanctions essentially shifts Russia’s accumulation of foreign assets away from the central bank and to some other entity that’s ostensibly private.

So why bother with this “buy ruble” demand?

It’s effectively the acknowledgment of a shift caused by sanctions where reserve accumulation flows from an entity that can’t do it (the central bank) to other entities that aren’t sanctioned because of the sanctions carve-outs for oil, gas, and commodities.

So Putin’s “buy ruble” demand is mostly just words.

Nonetheless, there is one important operational difference.

When the CBR buys hard currency and sells rubles, it creates ruble and expands the money supply. A “private” bank can’t print money, so the West’s gas inflows are now more ruble-positive than before.

That’s the result of Western sanctions and the CBR’s inability to intervene in foreign exchange markets, as it can’t accumulate foreign exchange reserves.

So the West’s consumption of Russian energy is helping to stabilize the ruble more than before.

But…

Much of the recovery in the ruble is fake, due to the impact of capital controls.

Capital controls prevent Russians from taking their money out of Russia and helps keep money in the currency.

But some of the recovery in the ruble back to the pre-invasion exchange rate is genuine and reflects Western Europe continuing to import energy from Russia.

That hard currency inflow is a steady demand for ruble.

Knock-on effects in other emerging market economies

Depreciation pressure also started to build across other emerging markets.

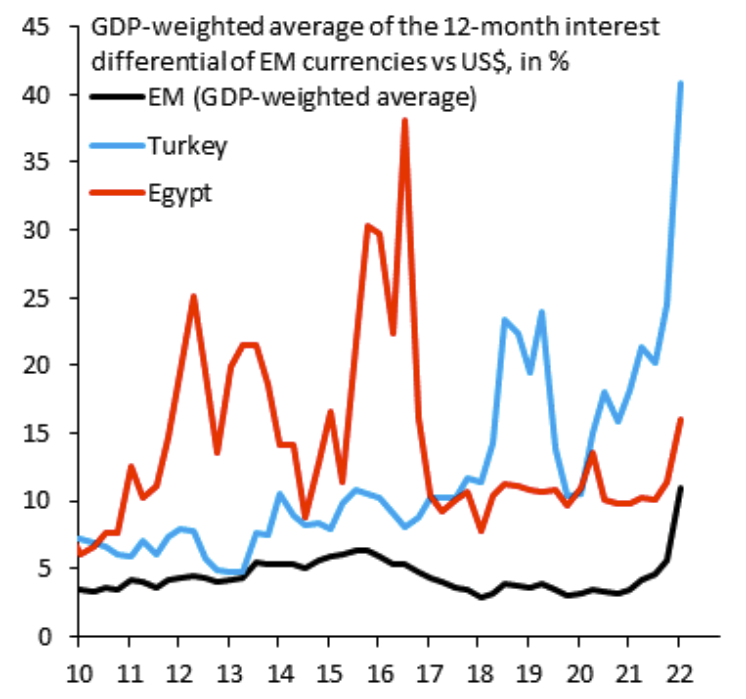

The Turkish Lira got hit, where depreciation 12 months forward blew out to 41 percent (blue). It is also hit Egypt, where the number rose to 16 percent from previously 10 percent (red). Rising food and energy prices are driving this due to the disruptions in these commodity markets.

Egypt is “short food” so when the price goes up, this is a hit on its balance of payments, causing currency weakness.

Turkey’s current account widening is especially worrying.

Turkey’s currency weakness is manifold:

- Weak underlying balance of payments

- Unorthodox CBRT policy (Erdogan believes interest rate cuts help curb inflation, contrary to virtually everyone else)

- Hits from the war in Ukraine, which means higher energy and food import costs, and

- Potential loss of tourism

The core measure of the current account deficit stood at -$7 billion in January 2022 (pre-Russia invasion before oil prices shot up – bad for an importer), more than twice as wide as in July 2018 (-$3 billion) before the balance of payments “sudden stop”. Depreciation pressure on the Lira became heavy.

Sri Lanka was also pressured into devaluation. It’s been pegged to the dollar. Virtually all economies hit by rising energy and commodity prices and those dependent on tourism from Russia and Ukraine saw devaluation pressure.

For currencies that are pegged to other currencies, like Egypt and Sri Lanka, policymakers typically react by letting it devalue all at once.

This helps the currencies establish a new appropriate equilibrium and establish a two-way market.

Defending the peg when the fundamentals don’t support the current exchange rate typically causes a country to burn through its FX reserves.

The economic impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war

Russia has lots of cash (i.e., hard currency – money it earned), given that its export revenues from oil and gas are very high.

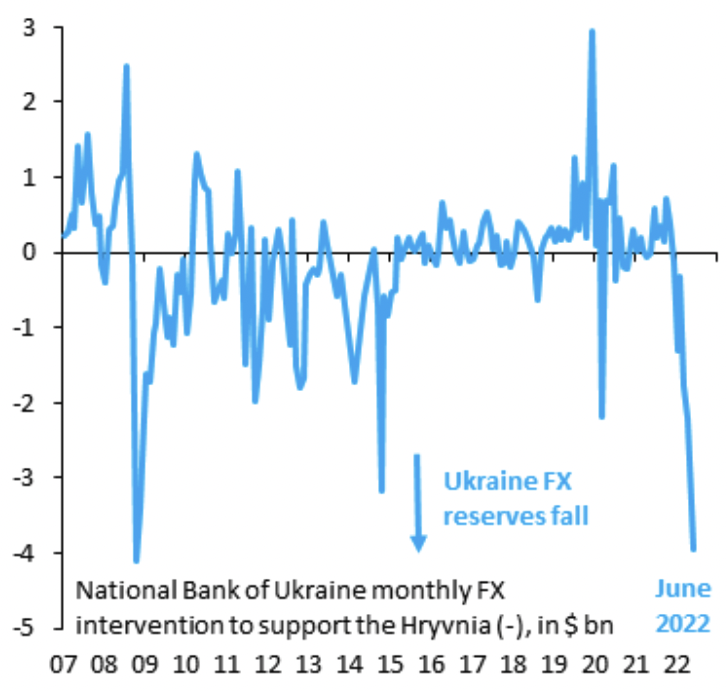

Russia’s central bank can therefore cut interest rates, while Ukraine is hiking rates in a desperate attempt to prevent devaluation and currency crisis.

(Source: IIF)

While there is lots of media attention on day-to-day events and military tactics, too little attention is placed on the economic plight in Ukraine.

War is expensive. Domestic tax collection has decreased at the same time.

So the central bank has printed money to finance spending for the war and domestic essentials.

That puts depreciation pressure on the Hryvnia (UAH), which the central bank tries to defend by selling FX reserves.

What’s bad for an economy isn’t always necessarily bad for the currency

Capital controls and interest rates increasing from 9.5 percent to 20 percent are among the reasons why the ruble’s exchange rate eventually decoupled from the Russian economy, despite a double-digit percentage contraction in 2022.

Raising interest rates helps attract savings into the currency (since it pays more). But higher interest rates change the incentives of borrowing and lending and can cause a contraction in credit creation. This can cause a drop in nominal and real GDP growth.

So while the currency can rise, the economy can sag.

Russia’s ability to invoice in the ruble

Russia’s ability to manufacture demand for the ruble is through captive commodity buyers.

Countries like Germany are so dependent on Russian oil and gas that Russia largely gets to dictate terms. If Moscow wants payment in rubles instead of euros or dollars it can do so.

For example, research by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) finds that the prices of traded goods move with the US dollar. (The US dollar is the world’s most prominent invoicing currency by a wide margin over the euro.)

This is true even in cases where neither country uses the dollar as their own domestic currency and their bilateral exchange rate shifts in some other direction.

This illustrates why invoicing in your own currency can give you power.

Foreign buyers also pay more when the exchange rate rises.

This is what Russia could get from ruble invoicing in oil, gas, and other commodities it sells to the rest of the world.

Yet, though natural gas is a somewhat segmented market, given the difficulty in transporting it long distances, Russia isn’t a big exporter of differentiated goods and finished goods with sticky prices.

Instead, it is a huge seller of commodities. And these prices fluctuate in real-time and move to offset changes in the dollar.

Further reading