To Hedge or Not to Hedge?

While equities and practically all financial assets were battered between February 19 and March 23, 2020, those who were long volatility, and put options in particular, either hedged well against losses or even made money.

Those with convex exposure to downside protection reaped remarkable returns in some cases.

This ignited debate over the use of hedging strategies and the use of options in a portfolio for not only protection and tail risk hedging, but as potential returns sources in themselves.

Key Takeaways – Hedging

- Long Volatility Strategies and Put Options

- During certain crisis, strategies involving long volatility and put options have proved effective in hedging against significant losses or even generating profits.

- These can be effective in bearish environments more generally.

- Convex Exposure Benefits

- Holding convex positions, like deep out-of-the-money put options, can yield substantial returns during market downturns, as seen with Universa Investments in early 2020.

- Hedging Costs

- While hedging can be expensive and may drag on long-term performance, it offers protection against catastrophic losses, akin to purchasing insurance.

- The key is to get the cost right and protect what you need to protect.

- Strategic Implementation

- Hedging should be tailored to portfolio needs, considering risk concentrations and acceptable loss thresholds.

- Options and futures provide flexible instruments for effective risk management.

Hedging in the context of risk management decisions

Many investment managers believe that hedging is too expensive. While it may produce huge returns in short periods, it’s met with “slow bleed” type of performance in most other times.

It’s a generalization, but we’ve also argued in other articles that the evidence suggests that hedging, on average, is expensive and a drag on long-term performance.

This is why many traders view volatility as a risk premium to be extracted from the market, if it can be done in a capable way. (Selling volatility without proper risk management can be disastrous.)

Even when big volatility events hit that knock the value of many types of portfolios, the losses often prove transitory even if they are very painful in the moment.

Options sellers want to be compensated for underwriting financial insurance.

On net, option buyers pay a premium above fair value for an option in the same way private insurance businesses charge more than what’s needed to mathematically offset expected risk. That way they have a viable, profitable business over the long-run.

As a result, option buyers will have to know that they’re paying too much for protection – or by buying options as capped-risk bullish or bearish wagers on their own – over the long term.

This occurs for the same reason we collectively overpay for various forms of insurance. It helps limit the financial damage of a devastating liability should one occur. Paying regular insurance premiums becomes a normal part of life to get rid of various forms of left-tail risk.

Similarly, financial insurance is useful to have in order to limit losses when you need a certain level of protection in your portfolio.

You always want to make the risk of what’s unacceptable nil.

Mark Spitznagel, the founder, owner, and chief investment officer of Universa Investments, argues against the idea that hedging is excessively expensive. Naturally, he makes a convexity argument in his support of his fund’s options-based strategy of being long deep OTM put options.

“When the market crashes, I want to make a whole lot, and when the market doesn’t crash, I want to lose a teeny, teeny amount. I want that asymmetry… that convexity.”

Some nonetheless believe the longer term drag on performance isn’t worth the sacrifice.

The struggle of value-based wagers

Since April 2010, now well more than a decade ago, value has struggled against other forms of equity-based strategies.

In theory, value investing makes sense. If you buy companies with high cash yields relative to their prices, you should be able to come out ahead over time.

The same is true with respect to other forms of investing, such as real estate, where the goal is to buy properties below market value to achieve a higher cash flow yield and/or future price appreciation.

But with low, zero, or negative yields on cash and/or bonds throughout developed markets, that’s pushed the yields on equities and other riskier forms of assets down as well.

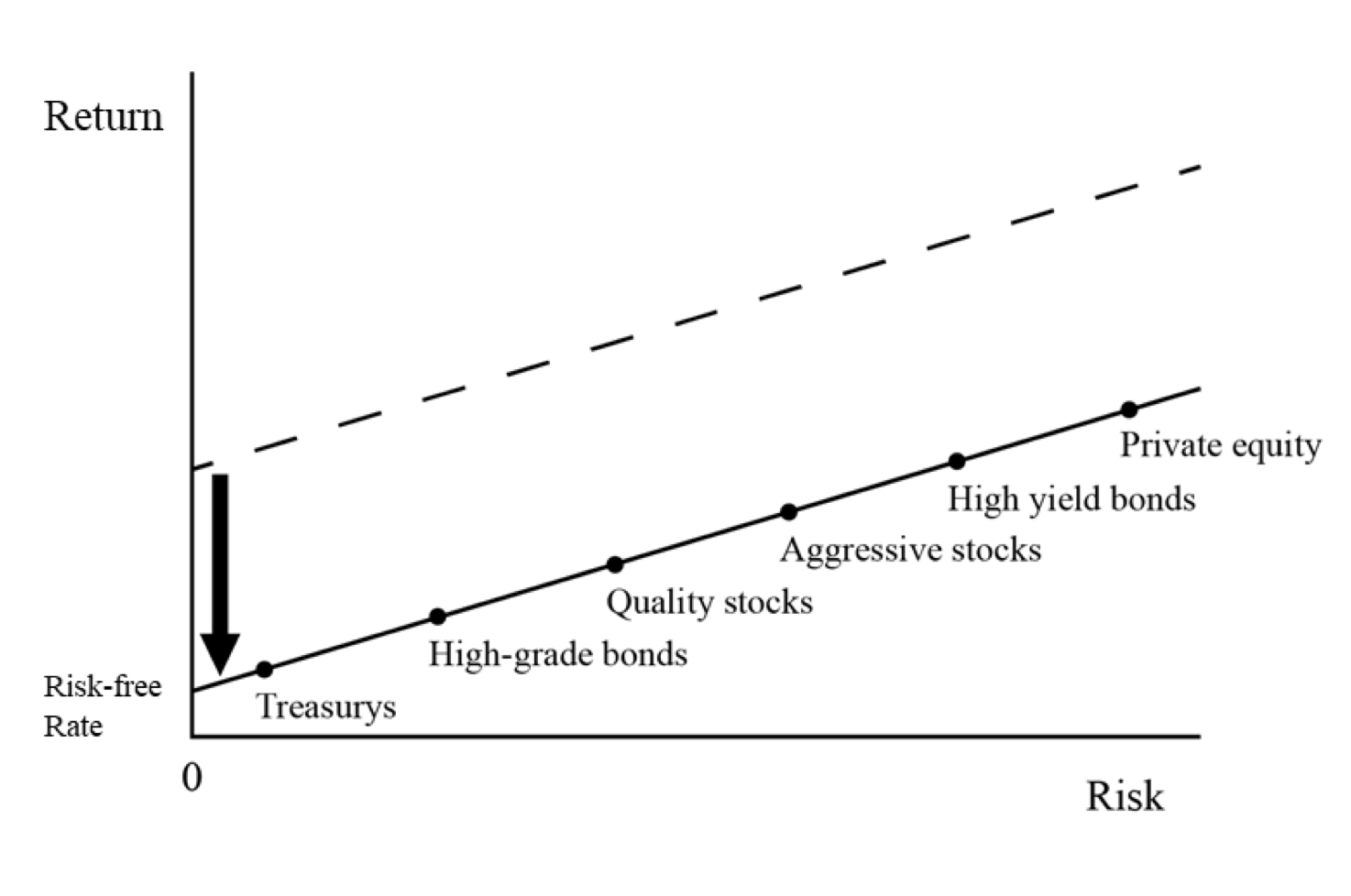

When interest rates decline, so do the yields of other assets

As a result, there have been few opportunities offering close to the traditional margin of safety that value investors like to have to sustain long-term gains.

All of the traditional metrics suggest a poor environment for value no matter what the metric:

– Shiller’s CAPE

– Tobin’s Q

– Market cap to GDP

Most value investors would consistently argue that the market is detached from its fundamentals and has been for a while.

But fundamentals to a value investor usually means seeking out a certain level of returns. Because of low interest rates pulling down the yields of everything else, it means that value investing in that sense isn’t going to work as well.

Long periods of below-normal volatility tend to sow the seeds of their own undoing. When volatility is low, yield becomes the more important factor to market participants.

This encourages leveraging up at the same time yields are declining as stocks go up. This buildup of financial leverage exacerbates shocks in the other direction when they do occur.

For example, if the forward yields on stocks goes from 5 percent to 4 percent, most investors still need the same returns as they did before. So, the inclination is to take on more leverage to magnify the smaller returns on equity into what they want or need.

Markets also have a tendency to extrapolate conditions forward even when it may not be appropriate to do so.

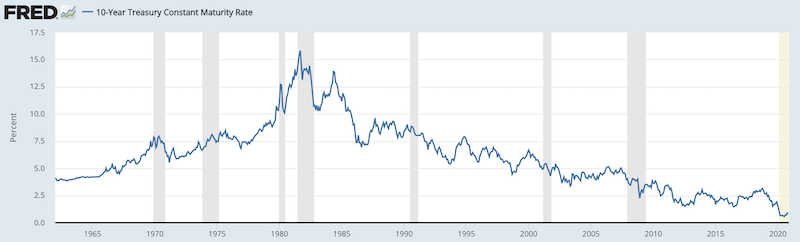

For example, since 1981 in the US, 10-year bond yields have gone from 15 percent to nearly zero.

That’s been a huge tailwind behind financial assets of all sorts due to how the discounting process works on the present values of financial assets, from bonds to stocks to real estate.

10-Year US Treasury decline from 1981 forward

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

With that interest rate tailwind largely out of gas, investors still bet heavily on stocks even when central banks can’t lower rates to help offset the drops in cash flows in a recession.

That creates more risk for equities. It also creates more demand for certain types of equities that have stable earnings – e.g., consumer staples, utilities – and those that are more instrumental in developing the leading technologies.

Some types of stocks can be considered stores of wealth if their earnings are relatively stable and predictable and their prices are not overly dependent on central bank or government action. Namely, they don’t necessarily need a big interest rate cut to offset a drop in earnings.

At the same time, you have influence from China coming up to challenge the West that’s causing countries to become more independent due to this conflict.

Instead of locating production where it’s cheapest, countries are having to think about creating independent supply chains even if it means lower margins. That contracts earnings and cash flow, holding all else equal.

The basic idea is that there is more tail risk than normal to go alongside high valuation concerns – i.e., lower forward returns at higher than normal risk.

Naturally, risk hedging tends to become the most expensive right around the time the market is at its bottom.

When risk is expensive, the price of protection against further damage becomes nearly prohibitive. At the same time, when the economy is having issues, policymakers have big incentives to get it going again.

Trading is difficult to do well because it forces people to do the opposite of their instincts.

When assets are high and volatility is low, there’s the bias to keep doing the things that work. In that case, owning stocks and shunning downside protection is common.

Likewise, when asset prices have just declined rapidly and volatility is high, then avoiding that pain becomes common by either selling assets or buying volatility.

But that’s the opposite of how it should work.

Preparedness for volatility and downswings in assets is wise. Therefore, holding hedges when assets are at record valuations and volatility is cheap may be prudent.

But it’s also dependent on the context of a portfolio.

Those who don’t own many stocks may not need tail risk hedging on equities unless they view such a tactic as a way to potentially add returns.

And once a huge drop has set in – e.g., 1932, 1974, 2009 – further downside risk is low due to the incentives to get everything going again.

Those in charge will do practically anything to save the system assuming they have the ability to (unique situations like Iceland in 2008 occur due to fears of losing their currency).

Financial assets are important because it provides a market for the money and credit that are used to help produce goods and services in the real economy.

Even though a war economy is very risky since the ultimate result of the war has big implications on who has control of what and who the dominant superpower(s) are, this was heavily reflected in asset prices.

When earnings ratios are single digits, this prices in double-digit forward earnings yields. (The inverse of the P/E is the implied yield.)

Similarly, 2008 may have been an extremely volatile environment in the latter third of the year. But assets were cheap and buying volatility was very expensive.

Many shrewd investors were selling puts in 2008, not buying them.

This can only be achieved when there is cash to put to work. Hedges help to achieve this purpose. When equity values decline, hedges help provide cash through their appreciation to offset losses or even add value to a portfolio on net.

Those who hold strictly to value strategies, however, are not likely to hold onto equities when their forward rates of return are expected to be low.

Instead, they might move up the quality ladder to things like corporate bonds or government bonds.

Eliminating risk in cost-effective ways

Universa works by putting up just 2 to 3 percent of its capital at risk on its tail risk hedging methods.

The funding for this, in effect, can be achieved by putting the remainder into safer investments (mostly cash and safe bonds) and using the interest and coupons that those throw off to fund the tail risk protection puts.

This means in a normal environment, where there are no big downswings in equity markets, the fund effectively remains neutral.

The puts expire out-of-the-money and the interest and coupons essentially pay for the loss.

In market routs, the safe investments still pay off while the put options can pay off very well.

This is also called a “barbell portfolio” because of the opposite nature of the two investment themes. It’s a strategy that loses little to nothing the vast majority of the time, followed by big gains infrequently to very infrequently.

For single-company wagers

Some traders will also do this with respect to certain companies to either hedge or make bullish or bearish options wagers in a limited risk way.

For example, if one is long a risky stock, one might want to limit one’s exposure to that. Limiting the position size is one way. But there are different ways to go about it.

If the stock has a public bond market, the trader could go long the underlying bonds and use the coupon payments from those to fund put option on the stock.

For example, let’s say the company has a bond yielding 3 percent per year. The trader could use that 3 percent to spend on put option to minimize any loss in the stock beyond a point. He would then be free to capture all the upside without worrying about unacceptable downside.

Likewise, this strategy can be used to fund outright bearish wagers. The cash flow from the bonds can fund put options to bet against a stock in a limited risk fashion.

If the bonds yield a certain amount per year, one could use the proceeds to fund put options one year out, if the idea was to match the two.

For example, if the bonds provide $1,000 in coupon payments, that could fund $1,000 worth of put options.

Of course, in this case, you have to think about the fact that your funding source (the bonds) are not entirely safe. But they’re much safer than the equity, as shareholders are paid last in a theoretical bankruptcy scenario.

Especially on the bearish wagers, if the bonds are having problem, you know that your bearish bet on the stock is probably panning out even more so.

When companies default on their debt, it often (but not always) zeroes out shareholders, which is the optimal outcome for a plain put option position.

Most common hedging arrangements

Let’s look at the most popular type of hedging arrangements.

We’ll structure this in terms of describing what they are and how to execute them.

1. Forward Contracts

- Description – Agreements to buy or sell an asset at a future date for a price agreed upon today.

- Execution – Customizable contracts typically traded over-the-counter (OTC). Commonly used by businesses to hedge against foreign exchange and commodity price fluctuations.

2. Futures Contracts

- Description – Standardized contracts traded on exchanges to buy or sell an asset at a specified future date and price.

- Execution – Requires margin accounts and adherence to exchange regulations. Widely used in commodities, interest rates, and stock indices.

3. Options

- Description – Contracts giving the holder the right, but not the obligation, to buy (call) or sell (put) an asset at a set price before a certain date.

- Execution – Can be traded on exchanges or OTC. Used for hedging equities, commodities, and currencies.

4. Swaps

- Description – Agreements to exchange cash flows or other financial instruments over a specified period.

- Execution – Common types include interest rate swaps and currency swaps. Typically executed OTC.

5. Hedge Funds

- Description – Investment firms that use diverse strategies to reduce risk, such as the use of derivatives and shorting to reduce market correlation.

- Execution – Managed by professional fund managers. Strategies include long/short equity, market neutral, and event-driven approaches.

6. ETFs (Exchange-Traded Funds)

- Description – Funds that trade on stock exchanges and hold assets such as stocks, commodities, or bonds.

- Execution – Purchased through brokers. Used to gain exposure to specific sectors or commodities while diversifying risk.

7. Currency Hedging

- Description – Techniques used to protect against currency risk.

- Execution – Instruments include forward contracts, futures, options, and swaps. Commonly used by multinational companies and investors/traders with foreign exposure.

8. Commodity Hedging

- Description – Protecting against price fluctuations in commodities like oil, gold, and agricultural products.

- Execution – Futures contracts and options are primary tools. Used by producers, consumers, and traders.

9. Interest Rate Hedging

- Description – Managing the risk of interest rate fluctuations. Or to control the cost of debt.

- Execution – Instruments include interest rate swaps, futures, and options. Used by financial institutions and corporations with significant debt (or interest rate risk).

10. Equity Hedging

- Description – Reducing exposure to stock market volatility. Or reducing correlation to the market.

- Execution – Strategies include buying put options, short selling, and using inverse ETFs (if day trading and not holding overnight). Applied by individual investors/traders and portfolio managers.

11. Credit Default Swaps (CDS)

- Description – Insurance-like contracts that transfer the credit risk of fixed-income products.

- Execution – Traded OTC; used by banks and traders/investors to hedge against the default of debt issuers.

12. Volatility Hedging

- Description – Managing the risk of changes in market volatility.

- Execution – Instruments include volatility index futures (e.g., VIX futures) and options. Used by traders seeking to protect against adverse market movements.

13. Inflation Hedging

- Description – Protecting against the eroding effect of inflation.

- Execution – Instruments include Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), commodities, and real estate investments.

14. Structured Products

- Description – Pre-packaged investments that typically include derivatives.

- Execution – Designed to meet specific risk-return profiles. Customized exposures. Sold by financial institutions to investors/traders looking for tailored solutions.

15. Dynamic Hedging

- Description – Continuously adjusting hedging positions in response to market movements.

- Execution – Requires sophisticated modeling and real-time monitoring. Used primarily by large financial institutions and hedge funds that have a sophisticated understanding of hedging.

Conclusion

The topic of hedging produces debate in trading circles. Hedging is costly, but can produce benefits in excess of the costs if done prudently.

2008 forced many traders to reconsider how they structure their portfolios.

Like many things, there is no black and white, “0” or “1” answer. There’s a lot of gray and is dependent on context.

Generally, it is advisable to consider hedging when there are concentrated risk exposures in a portfolio or when it’s unacceptable to lose beyond a certain amount.

For a portfolio that is long a lot of stocks, if a 20 percent drop in the equity value of the portfolio would be too costly, then one could consider hedging that out.

One can also improve return relative to risk in other ways, such as avoiding concentrated exposures and balancing among different asset classes, including stocks, bonds, cash, and even some amount of commodities and/or gold.

For any type of risk exposure, there can be a benefit to limiting it or getting rid of it altogether.

Risk can also be mitigated in ways that minimize the cost, such as using the coupons from safe bonds to fund put options to protect against the riskier parts of a portfolio.