Swaps

A swap is a type of derivative contract where two or more parties are involved in a contract to exchange – or “swap” – cash flows or liabilities over a specified period of time. The way contracts work, and the way investors make money from them, are relatively complex and can seem arcane to retail investors. However, swaps are big business for institutional investors, and make up a significant part of the derivatives market. In 2020, the notional value – the sum of all long and short positions – of the entire swaps market was estimated at more than $500 trillion.

This tutorial will act as your swaps 101, giving you a rundown of the history of swaps; a guide to different varieties of contracts and their distinctive features; useful information, definitions and examples. It also covers tips on how individual investors can use knowledge of the swap market to boost their trading strategies.

For retail traders looking to speculate on financial markets with derivative instruments, see our list of top brokers below.

Derivatives Trading Brokers

Swap Trading Basics

Firstly, a brief answer to the questions that can mystify rookies: What does “swaps” mean on the trading floor, and how do they differ from other derivatives like futures and options?

A swap refers to a contract between two counterparties who agree to exchange financial instruments, cash flows, payments, or liabilities over a set time period according to pre-specified conditions. In practical terms, this can be seen as a series of forward contracts between the two counterparties with common exchange dates.

The cash flows or financial instruments which are swapped in this exchange are known as “legs”, and often one of these legs’ values is fixed while the other is set to a variable amount such as an index price or interest rate. So, unlike futures and options contracts, in a swap each side provides its own underlying asset to the diversity, and a swap trade typically involves a series of payments over the term of the contract, from the beginning or the “effective date” through a number of “settlement dates” to the final or “termination date”.

One benefit of swap contracts is that they allow investors to take advantage of an interest rate or market they otherwise would not have access to. Contracts can also help investors manage risk by hedging, or they can facilitate long or short positions against a variety of financial assets.

Swaps are almost always created as tailor-made contracts traded over the counter (OTC) to large firms and institutional investors and not on an exchange, and as such are not widely available to retail traders. However, there are some exceptions to this, which will be discussed below.

History Of Swaps

The origin of swap trading goes back to the 1970s, when companies operating in Britain would set up agreements with counterparties in foreign countries in order to get around the British high tax rate on currency exchanges involving the British pound sterling.

The counterparties would set up loans in their respective countries and swap them, allowing each side access to the other’s currency without having to implement a currency exchange and pay tax on it. This was the prototype for the modern currency swap, though the first formalised swap agreement would not appear until 1981.

The 1981 World Bank–IBM swap

When the World Bank entered a contract to exchange its own supply of U.S. dollars with Deutsche marks and Swiss francs borrowed by IBM, the world’s first formal swap agreement came into being.

The need for swap trading came about because there was a high demand for Swiss francs and Deutsche marks among the World Bank’s customers, which the bank was unable to supply due to limits on borrowing imposed by the Swiss and German governments. Salomon Brothers came up with a solution: the World Bank could “swap” its borrowed USD with IBM, which already had a large amount of Swiss and German currency but was looking to increase its USD holdings.

This financial innovation allowed the World Bank to circumvent the borrowing limits and access Swiss francs and Deutsche marks, while also providing IBM with the USD supply it needed at a favourable exchange rate.

The 1981 World Bank-IBM swap paved the way for a slew of innovative financial instruments built around exchanging cash flows or liabilities, which we will delve into in our next section.

Who Uses Swaps?

Many countries’ governments use swaps to help manage risks associated with floating interest rates and foreign currency exposures.

Some companies use swaps to hedge their own interest rate and money-market exposures or their future revenue streams.

Even some individuals and smaller firms can find swaps to be useful tools for hedging or speculation.

Types Of Swaps

As we’ve seen, originally swaps contracts provided access to foreign currencies and allowed counterparties to get around restrictive taxes. Since 1981, similar models have been created for a variety of purposes, making swaps an extremely diverse category of financial instruments. Some of the common types are:

- Foreign exchange swaps

- Total return swaps

- Credit default swaps

- Interest rate swaps

- Commodity swaps

- Currency swaps

- Equity swaps

- Inflation swaps

- Vol swaps vs var swaps

Interest Rate Swaps

One common type of swap is an interest rate swap (IRS), which refers to swaps dealing with interest payment obligations or receipts.

They involve two counterparties exchanging a stream of cash flows over an agreed time period based on either one or more benchmark interest rates. Classically, this meant a rate benchmark such as Libor (London Interbank Offered Rate), Euribor (Euro Interbank Offered Rate), or TBA – LIBOR (The Brokers Offered Rate).

Now that Libor is being phased out due to a series of rigging scandals, other interest rate benchmarks have been set up in their place, such as SOFR.

They will also usually involve the exchange of a final cash flow called the ‘termination payment’ or ‘termination value’ at some point determined by an agreed formula, analogous to a final principal payment for a bond.

For example, swaps based on Libor may stipulate that if one party swaps variable rates with another and it swaps back to fixed with them in the future, they must swap back to the same rate as the original swap or prevailing market rates.

These products can be used for hedging purposes, such as when companies use swaps to lock into interest rates for borrowing over various periods while protecting themselves from any significant rise or fall in interest rates.

Another important distinction is that an interest rate swap is an agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows that are based on a notional principal amount and an agreed interest rate or rates denominated in a single currency. Those denominated in two different currencies – i.e., a cross-currency interest rate swap – are typically called quanto swaps.

Cash flows as they pertain to interest rate swaps could involve periodic interest payments at agreed intervals, such as quarterly, semi-annually, or annually.

But the term ‘interest rate swap’ may also refer to swaps where there is only a single final value exchanged, often referred to as an ‘accreting swap’.

Swaps involving multiple cash flow exchanges can be divided into those with a principal repayment leg and those without.

The latter swaps could either have no final payment due upon maturity (a ‘bulleting swap’) or may involve a ‘balloon payment’ at the end – usually calculated so as to ensure that the present value of this is equal to the original notional principal amount.

One example of swaps involving both principal and interest would be swaps based on Libor where one party swaps variable rates with another and it swaps back to fixed with them in future, they must swap back to the same rate as the original swap or prevailing market rates.

The notional principal amount will often be used as the basis for determining the day count convention (and interest accruals if appropriate) but such agreements tend to vary between counterparties and swaps will therefore often contain a clause dealing with such terms.

Rather than paying coupon payments periodically, swaps can be set up to accrue interest on a notional principal amount. For swaps with no final maturity, the calculation of the final payment is based on an agreed formula that takes into consideration multiple factors, such as indices determined by reference rates, current market rates at the end date, etc.

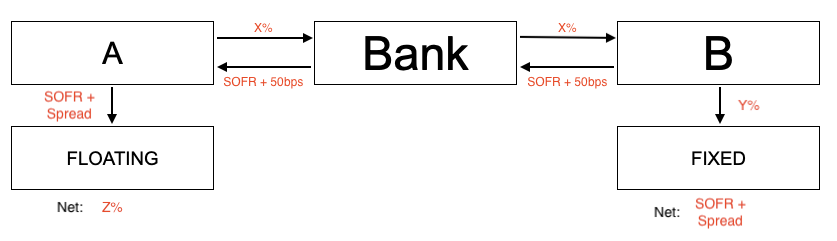

Swap illustration

In the above diagram:

A is currently paying the floating rate, but wants to reduce interest rate risk by paying a fixed rate.

B is currently paying the fixed rate but wants to pay a floating rate due to the nature of its asset and liability mix.

Both parties can enter into an interest rate swap agreement using a bank as an intermediary. The net result is that both A and B can ‘swap’ their existing set of obligations or exposures for their desired obligations or exposures.

Typically A and B do not transact directly with each other.

Each will set up a separate swap with a bank or other institution (e.g., hedge fund, nonbank institution).

For coordinating the deal, the bank will take a spread from the swap payments.

Futures Swaps

Futures swaps are an agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows of one asset for another at various pre-determined points in the future, usually according to a fixed schedule.

They will often use a fixed interest rate, and in some cases may involve a final lump sum payment or receipt upon maturity known as a ‘final settlement price’ agreed over the life of the swap contract.

For example, swaps based on Libor may stipulate that if one party swaps variable rates with another and it swaps back to fixed with them in the future, they must swap back to the same rate as the swap or prevailing market rates.

Basis Swaps

A basis swap refers to swaps where counterparties exchange either fixed-rate payments representing the difference between two floating-rate indices, or floating-rate payments based on a fixed spread relative to different floating-rate indices.

For example, swaps based on SOFR may stipulate that if one party swaps variable rates with another and it swaps back to fixed with them in the future, they must swap back to the same rate as the original swap or prevailing market rates.

Freight Swaps

A freight swap (also known as shipping swaps) is an agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows of both parties’ obligations relating to one leg of a freight contract for those related to the other leg of the same contract.

This results in each leg having its own price benchmark, which may be a specific trip/voyage or contract period.

Currency Swaps

As seen in the 1981 deal, a currency swap involves the two parties exchanging the principal and interest of a loan in one currency for the principal and interest of a loan in another.

The principal amounts are exchanged at the beginning of the contract at spot rates, to be exchanged back at the end of the swap either at spot rates or at a previously agreed rate. For example, the parties can agree to trade principals back at the original rate once the life cycle of the currency swap comes to completion to protect both sides from the risk involved in currency fluctuations.

Currency swaps often work as a trading mechanism that allows companies to obtain advantageous interest rates on foreign currency loans. The structure of a currency swap also makes it useful as a hedge against the interest rate of an already held loan.

Forex Swaps

Foreign exchange swaps, also known as forex or FX swaps, work in a very similar way to currency swaps. The difference between them is that the counterparties do not necessarily pay interest on the loans throughout the duration of the swap.

A forex swap usually consists of two legs. At the first, the respective parties buy and sell two foreign currencies at the sport rate. The second leg comes at the end of the swap, when they reverse the transaction to trade back their original currencies at a forward rate. Forex swaps are often used to hedge against short-term currency fluctuations.

Commodity Swaps

In a commodity swap, the two counterparties agree to exchange cash flows in a contract where one leg is tied to the market price of a commodity. Commodity swaps are usually set out in customized contracts, with the fixed leg usually held by the commodity producer and the floating leg held by the consumer or financial institution.

This type of swap contract is particularly useful for producers and consumers who wish to hedge against price fluctuations in a given commodity – most commonly, in oil trading. Swaps based on oil and other fossil fuels are sometimes known as energy swaps.

Credit Default Swaps

In trading, credit default swaps refer to a type of derivatives contract that allows investors to offload the risk of an investment to another party. A credit default swap involves a lender buying a contract from another investor, who undertakes to compensate the lender in the event that a borrower defaults.

A credit default swap must involve at least three parties: the borrower, or debt issuer; the creditor or debt buyer; and the credit default swap seller, usually a large bank or financial institution.

At the first stage, when issuing the debt, the debt issuer agrees to pay back the principal amount when the debt matures, as well as regular interest payments. Since the loan period can be very long, risks can be difficult to gauge in a loan – the debt issuer may go out of business long before the date of maturity and be forced to default. A credit default swap acts as insurance for the debt buyer that if the debt issuer defaults, the credit default swap seller will step in and pay the buyer the value of the security plus interest.

Total Return Swaps

In a total return swap, one party makes payments according to a fixed rate while the counterparty’s payments are linked to the return of an underlying asset. This is considered useful as it allows an investor to gain exposure to the reference asset without actually owning it.

Vol Swaps/Var Swaps

Volatility swaps, or vol swaps, are not swap contracts in the traditional sense of counterparties trading cash flows. Rather, they are a type of derivative similar to a forward contract that allows a trader to speculate on the future volatility of an underlying asset. In a vol swap, a trader will set up a forward contract with a strike price based on the current implied volatility of an asset. When the contract matures, if the realized volatility is higher than the strike price, the contract buyer will profit, while the seller stands to gain if it is lower.

Variance or var swaps work in the same way, but in their case the payout is determined by the variance – volatility squared – of an asset. This type of swap is more common than volatility swaps on the equity market.

Both these types are used to speculate and hedge, and common strategies for vol and var swaps include dispersion trading.

Inflation Swaps

An inflation-linked swap is an agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows of both parties’ obligations where at least one obligation is linked to inflation.

This swap deal can also involve cash flows denominated in different currencies and are most useful when one party expects to receive payments in a currency whose real value is highly uncertain due to a history of inflation (or ongoing high inflation).

Option Swaps

An option swap, or swaption, allows the purchaser the right, but not the obligation, to buy (or sell) predefined amounts of an underlying asset from (or to) the seller over a certain period of time at a pre-agreed price.

This type of swap usually specifies whether or not the option can be altered or terminated during its life cycle and how any such changes would affect the payment stream.

Subordinated Risk Swaps

A subordinated risk swap (SRS), or equity risk swap, is a swaps agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows of both parties’ obligations where at least one obligation is linked to equity.

This type of swaps deals with cash flows denominated in different currencies and are most useful when one party expects to receive payments in a currency whose value depends on inflation.

Equity Swaps

An equity swap is a swaps agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows of both parties’ obligations where at least one obligation is linked to the change in value of a particular stock equity index.

In a typical equity swap, one party will agree to pay the other party a stream of payments that is based on the performance of an equity index or a basket of stocks. Less commonly, it is based on a single stock.

In exchange, the other party pays a fixed rate or another floating rate.

The two parties can agree to swap payments at regular intervals (e.g., every three months), or they can choose to settle up at the end of the contract period.

The equity that’s used as collateral in an equity swap can be shares of stock, an equity index (such as the S&P 500 or an MSCI index), or a basket of stocks.

The baskets are usually made up of stocks from the same industry vertical (e.g., consumer staples, utilities) or region, which helps to minimize risk.

Read more: Equity Swaps – What to Know

Total Return Swap

A total return swap is swaps agreement between two parties that consists of a series of exchanges over the life of the swaps.

The party paying the total return makes payments based on a notional amount, usually representing an investment in some security or index, which varies with the performance of that instrument. The other party makes payments initially set at the contracted rate and then adjusted to offset any change in interest rates during swaps’ life cycle .

Variance Swap

Variance swaps are an over-the-counter financial derivative used to hedge risks and/or speculate on the price action of a certain asset, index, volatility measurement, interest rate, or exchange rate.

One leg of the variance swap pays an amount based on the realized variance of the price changes as it relates to the underlying asset, index, etc.). Because this is unknown ahead of time, it pays what’s commonly called a floating rate.

Price changes are typically noted as log returns. Normally these are taken on a daily timeframe based on some agreed-upon closing price (e.g., such as the 4 PM EST weekday close of a stock on the NASDAQ or NYSE).

The other leg of the swap pays a fixed amount. As suggested by the term fixed, this amount is known when entering the deal.

The net payoff to parties involved in the deal will be the difference between the fixed amount and the floating amount at the end of the deal.

This is much like a standard vanilla option when the premium is known once entered and the final payout is determined at expiry.

Like vanilla options, the variance swap is settled in cash at expiration.

However, occasionally, cash payments are made at some interval for purposes of maintenance margin.

Basket Swaps

This type of swap consists of exchanging cash flows denominated in different currencies but linked to one or several assets contained in a certain basket.

For example, China has historically managed its currency against what’s known as the CFETS basket, which is a mix of different currencies from around the world, roughly based on their importance in the global economy.

Forward Swaps

A forward swap is an agreement that swaps the difference between the contracted date and present value of cash flows occurring at a later date.

This type of swap offers more security than swaps since the later payoff is guaranteed.

It is also commonly called a deferred or delayed-start swap.

Constant Maturity Swaps (CMS)

A constant maturity swap allows the purchaser to fix the duration of received flows on a swap.

In a constant maturity swaps contract, the buyer receives payments based on a floating interest rate and pays according to a predetermined fixed rate. In addition, these payments will continue over the life of the swaps agreement unless it reaches its termination date, at which point it would be exchanged for the notional value.

In particular cases such as CMS swaps, one party’s payment is linked to a reference portfolio’s average price during its life cycle, while the other party’s payment is linked to a reference rate.

The reference portfolio can consist of a predetermined basket of bonds or loans whose prices are directly accessible on the market.

Asian Swaps

An Asian swap is an agreement with early termination if predefined criteria are met, most commonly the average price of a security between start and end date of the agreement being different from by a certain amount. This type of swap requires additional conditions, such as a minimum number of days.

This is similar to the idea of an “Asian” option because it offers early termination when certain conditions are met based upon the average price of this asset over time.

Bond Basis Swap

This type of swap consists in exchanging floating-rate payments for fixed-rate payments linked to a swap’s underlying bond.

Offset Swaps

An offset swap is a swap agreement where the payout at maturity is calculated by adding together gains and losses generated during the swap’s life cycle.

If one leg has a loss equivalent to the swaps principal, then there is no payment (or vice versa).

Constant Proportion Portfolio Insurance (CPPI) Swap

A CPPI swap is a type of portfolio insurance where a trader or investor wants to set a floor on the dollar value of their portfolio, then will decide on asset allocation decisions based on that.

The concept of CPPI uses two different assets in a type of barbell approach. These consist of a risky asset (usually equities, ETFs, or mutual funds) and a conservative asset of either cash, cash equivalents, or safe government bonds.

The percentage allocated to each type of asset depends on how much “cushion” a portfolio has, which is defined as current portfolio value minus floor value, plus a multiplier coefficient. A higher multiplier denotes a more aggressive strategy.

A CPPI swap can be used to replicate buying protection from a given underlying asset at maturity in case that its price drops below an agreed upon level during the swap’s life cycle, paying the difference between the market’s price at time T and this predetermined level.

Amortizing Swap

An amortizing swap is typically an interest rate swap where the notional principal for the interest payments declines over the life of the swap.

This rate can be tied to an interest rate benchmark (such as SOFR) or to the prepayment of a mortgage.

It is a useful type of tool for those who want to manage the interest rate risk involved in a certain funding or lending requirement, or investment program.

Zero Coupon Swap

A zero coupon swap is useful when one party has liabilities denominated in floating rates but would like to minimize their cash outlay.

Sell/Buy-Back Swap

A sell/buy-back swap consists swaps agreement between two parties for one party selling an asset to another party and simultaneously agreeing to repurchase it on a future date at a predefined price.

This is usually done because the asset has matured and the seller wishes to close their position, or because they wish to hedge other business activities such as exchanges transactions, among others.

Deferred Rate Swap

A deferred rate swap is useful for those who need funding right now but don’t find current interest rates attractive and believe rates may fall in the future.

Receive-Fixed Swap

A receive-fixed swap consists of an agreement between two parties where one party agrees to pay a fixed rate and another party agrees to pay a floating interest rate based on an underlying index (such as Libor, SOFR, Euribor, etc.).

Interest Rate Collar

An interest rate collar is a combination of puts and calls used to hedge against rises in interest rates over time while allowing returns from assets denominated in floating rates.

This type of swap is useful when one party wishes swaps limits losses from rising interest rates, while still accessing floating-rate cash flows.

Accreting Swap

An accreting swap is used by banks that have agreed to lend increasing amounts of money to their customers over time so that they may fund projects.

Forward Swap

A forward swap is formed via the synthesis of two swaps differing in duration for the purpose of fulfilling the specific timeframe needs of an investor or company.

A forward swap is also known as a:

- forward start swap

- delayed start swap, or a

- deferred start swap

Quanto Swap

A quanto swap is a cross-currency interest rate swap in which one counterparty pays an interest rate in a separate currency to the other party but the notional amount in domestic currency.

The payor side of the swap may be paying a fixed or floating rate.

For example, a swap in which the notional amount is denominated in British pounds, but where the floating rate is set as USD SOFR, would be considered a type of quanto swap.

Quanto swaps are also commonly known as differential, rate-differential, or diff swaps.

Range Accrual Swap (Range Accrual Note)

A range accrual swap (or range accrual note) is an agreement to pay a fixed or floating rate while receiving cash flows from a fixed or floating rate on days where a floating rate stays within a predefined range.

This enables swaps issuers to access the floating-rate market while at the same time hedging against rising rates.

Range accrual notes are also known as fixing note swaps.

Non-Deliverable Forwards (NDFs)

A non-deliverable forward is a swap agreement between two parties for an amount of foreign currency to be exchanged at a specified future date or during an agreed period.

Three-Zone Digital Swap

A three-zone digital swap is a generalization of the range accrual swap.

The payer of a fixed rate receives a floating rate if:

a) that rate stays within a certain predefined range, or

b) a fixed rate if the floating rate goes above the range, or

c) a different fixed rate if the floating rate falls below the range

Other Types Of Swaps

Investors may hear about swaps in other contexts, such as crypto trading or real estate. In these cases, the swap in question does not work in the same way as a financial derivative. Rather,

- Crypto swaps allow investors to directly exchange cryptocurrencies or tokens without going through the spot market. The swap function is available on crypto trading apps and platforms like Trader Joe’s, and is useful because unlike spot trade it allows users to instantaneously convert their tokens.

- Real estate or property swaps, also referred to as like-kind swaps, are a mechanism by which real estate investors defer capital gains taxes when they sell a property by exchanging it for another property of the same type instead of cash.

- A swap in the context of the Contract for Difference (CFD) type of derivative refers to the payment of interest accrued by a CFD held overnight.

To avoid confusion, traders should remember the marked difference between these types of swaps and the derivatives contracts described above.

How To Trade Swaps

The market consists almost entirely of over-the-counter contracts which are not available to retail traders, and the sheer monetary value of cash flows involved in this type of derivative mean that generally only large firms and institutions trade in swaps.

As a result, most traders will not need to acquire a deep knowledge of the swaps market unless their job requires it. If your career does bring you into contact with the swaps trading desk, you should make it a priority to quickly learn who the main players and market makers are in whichever swap market your company operates in, as well as the regulatory framework they operate under.

NFA Swap Firm Vs Swap Dealer

In 2010 U.S. legislation in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, the SEC defined swap dealers as entities that make markets in swaps or regularly enter into contracts as counterparties. Dealers are also known as swap brokers.

Swap firms, on the other hand, are not a registered category in the same way as brokers, but the name given to any company that is a member of the National Futures Association (NFA) and engages in swaps either exclusively or as part of its futures activities.

Regulators

In the United States, swaps trades are broadly overseen by the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), while the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has regulatory authority over security-based swaps. Since swaps are OTC contracts and not traded through exchanges or with the mediation of clearing houses, they carry the risk of one side defaulting.

However, the CFTC regulation provides a level of scrutiny to the market through regular reporting, as well as through regulations including margin rules for swap bank dealers, execution requirements specifying the markets where swaps can take place, and standardized relationship documentation requirements for contract participants.

Additionally, the 2010 legislation instituted centralized facilities for swap trade data reporting and record-keeping known as swap data repositories. This has made it possible to implement surveillance of OTC markets in the same way as other large markets are monitored.

Retail Investors

As mentioned above, swaps are not commonly available to retail investors through most trading websites, online apps and electronic trading platforms. However, some online brokers such as Interactive Brokers, do provide access to these instruments even for individual traders and investors.

Swaps Strategies

Since most individual investors will not enter a swap contract, they will not generally need to devise a system, model or strategy for trading FX swaps, interest rate swaps, and so on. However, they can be a useful way to evaluate market dynamics and get an idea of risk levels and other factors to help them make informed decisions in day trading and other trades.

So, it’s always a good idea to brush up on your knowledge of swap trading through guide sites like Daytrading.com, as well as YouTube and trading books. Some financial institutions may also provide materials in PDF form, such as Morgan Stanley’s “Using and Trading Asset Swaps”.

Swap Spreads

While a government bond is considered a risk-free investment, other debts hold the inherent risk that the debt issuer will default. Interest rates thus include a premium to account for this risk.

A swap spread is the difference between the fixed leg of a swap contract and the yield on a government bond of the same maturity. A wider spread indicates that more parties are willing to pay a higher price to hedge against perceived risk. This indicates a higher risk aversion in the market, and it can be a sign of reduced liquidity. This makes it a useful gauge for retail traders studying a given market to make potential trades.

Credit Default Swaps As Indicators

Similarly, credit default swaps can make good indicators signalling how a market views the risk of the entity on which a CDS is available, since the perceived risk of default will be priced into the spread of a CDS contract. Additionally, studies have shown that the CDS market can have a profound influence on adjacent markets, for example through a spillover effect of liquidity from CDS to corporate bond trading.

Swap Markets In The News

Since a large part of the massive derivatives market is tied up in swaps, it is always worthwhile keeping an eye on headlines related to swaps contracts as they can have a significant effect on the market as a whole.

For example, one of the biggest fears in the aftermath of the UK’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union was that this would drive swaps trading out of the City to EU or US platforms. The flow of swaps trading away from London was seen as a very pessimistic indicator for British financial markets, though there has been better news on that front as the UK regained top spot in sterling interest rate swaps in 2022, indicating a marked uptick in the interest rate swaps trading volumes.

Similarly, the euro interest rate swap market is one of the largest and most liquid in the world, and as such the euro swap curve is considered an extremely important interest rate benchmark.

Final Word On Trading Swaps

Swaps are legal agreements which fluidly trade cash flows over time. Swaps can be designed to function like a simple cap or floor, or like an exotic derivative with multiple embedded options that depend on various market factors.

As interest rates are the most fundamental backbone of finance, the simplest swaps only exchange two interest rate payments, commonly known as interest rate swaps. But there are dozens of kinds of swaps in practice.

While most swaps result from seeking exposure to returns on investment instruments, swaps are also created for hedging purposes.

Swaps are used by corporations, governments, and financial institutions to achieve various investment goals.

They are particularly useful for hedging interest rate risk, generating income from difficult-to-access markets, and for managing liabilities whose value depends on factors such as inflation rates, exchange rates, and other risk factors.

As swaps provide several benefits, including risk transfer, swaps are becoming increasingly popular over time.

However, swaps are also risky because they often involve counterparty risk. This means an institution may renege on its obligation if it can’t pay, among other reasons.

For retail traders looking to speculate on financial markets with derivative instruments, see our guide along with the best brokers here.

FAQs

Why Trade Swaps?

Like other derivative instruments, swaps can be useful both as speculative tools or for hedging purposes. One major difference is that swap trading can also work as a mechanism allowing companies to bypass restrictive regulation, access new markets or currencies, and avoid the cost of currency exchange fees or taxes.

Are Swaps Traded On An Exchange?

Swap contracts are usually tailor-made over the counter and are not available on most exchanges.

Where Do Companies Trade Swaps?

Companies and institutions across the world are able to enter swap contracts, and many do so to obtain favourable interest rates or currency exchange rates, or to hedge against risk. The main markets for swaps are in the UK, the EU and the United States, but swaps trading is big business and deals are made all over the world, from Sydney, Australia to Mumbai, India.

When Are Swaps Markets Open?

Swap contracts are tailor-made and not standardized contracts available on exchanges, so the exact terms of a contract may be hashed out whenever it suits the parties involved. Having said that, the opening times of companies involved are likely to follow regular schedule or trading hours and days in their respective countries.

What Are The Risks Involved In Trading Swaps?

As with any derivative contract, investors run the risk of losing money if their position proves to be unprofitable – for example, if they hold a short position on an interest rate swap and rates increase.

Since swap contracts are generally sold over the country and not through an exchange or clearing house, the swap participants must bear the additional risk that a counterparty may default.

Are Swap Contracts Available On Platforms Like Trading 212?

The “swap” referred to on trading platforms like Trading 212 which serve individual investors most probably do not refer to swap contracts like those discussed on this page. It is much more likely that they refer to the overnight interest rate charged for holding a position outside business hours or over the weekend.