Interest Rate Swaps

Interest rate swaps are a trading area that’s not widely explored by non-institutional investors, largely because of the lack of mainstream coverage and availability provided by online brokers.

Some, however, like Interactive Brokers, do provide access to these instruments even for individual traders and investors.

Let’s go through what these are and their role.

Key Takeaways – Interest Rate Swaps

- Interest Rate Swaps Allow Hedging or Speculation

- Traders use swaps to hedge against interest rate movements or speculate on future changes

- They exchange fixed interest payments for floating rates, or vice versa, to manage risk or seek profit.

- Determine Exposure to Rate Changes

- Understanding how swap rates reflect expectations of future interest rates can inform trading strategies.

- Market Perception Influences Swap Rates

- Swap rates are sensitive to market perceptions of future interest rate changes, central bank policies, and economic indicators.

What Is an Interest Rate Swap?

An interest rate swap is an interest rate derivative product that trades over the counter (OTC). It is an agreement between two parties to exchange one stream of interest payments for a different stream, over a certain period of time.

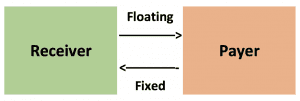

Most interest rate products have a “fixed leg” and a “floating leg”. This means that Party A will pay the fixed leg to Party B, while Party B will pay the floating leg to Party A. This is one way for investors or traders to bet on changes in interest rates. For corporations, banks, and other entities, it is a method to ensure that movements in interest rates don’t adversely affect their finances.

The swaps that exchange fixed rate payments for floating rate payments are generally termed “vanilla” swaps. Pre-2022 they were typically based on the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), which covers the US dollar (USD), EMU euro (EUR), British pound (GBP), Japanese yen (JPY), and Swiss franc (CHF).

Other overnight rates include SHIBOR (Chinese renminbi), HIBOR (Hong Kong dollars), EURIBOR (euro), STIBOR (Swedish krona), and SOFR, which is tied to the US Treasuries repurchase market.

In August 2018, Barclays was the first to sell short-term commercial paper off SOFR, as part of the expected LIBOR phase out. This was completed due to the frequent rigging of the rate by rogue traders.

High credit quality commercial and investment banks are market makers in the swap market. These entities offer both fixed rate and floating rate cash flows to those participating in the swap market.

After a bank executes a swap transaction to a client, it will obtain a fee for facilitating the transaction. If a particular transaction is large, a bank will normally execute the transaction through an inter-broker dealer. This intermediary will then disperse the interest rate risk associated with the instrument by selling it to several counterparties.

History and Purpose of the Interest Rate Swap

Interest rate swaps initially allowed companies to offset the risk associated with their floating-rate liabilities. The swap allows them to effectively convert this debt to fixed rates while receiving the floating-rate payments.

In other words, the corporation would pay the fixed rate. At the same time, any adverse effect on their debt – i.e., the interest rate the loan or bond is pegged to goes up – they would receive the cash payment from the swap to offset the extra compensation they would have to pay to creditors.

Also, companies can do the opposite. If the interest rate they pay on their debt is fixed, they can choose to pay the floating rate.

Since interest rates are a market in themselves, and swaps reflect the market’s future expectations of their direction, there is also interest in these instruments from traders, investors, and other bank and non-bank institutions. They provide a way to bet on their direction or for market participants to express their opinions on the future shape of the yield curve (e.g., being bullish on some part and bearish on another), or one country’s interest rate versus that of another, and so forth.

There are two main parties involved in a swap rate transaction:

- Receiver – pays the floating rate interest

- Payer – pays the fixed rate interest

What Specifically is the “Swap Rate”?

The swap rate is the fixed interest rate that the receiver requires as compensation for the risk involved in having to pay the short-term floating rate (e.g., LIBOR) over the life of the agreement.

The market’s expectations of what this rate will be is reflected in the yield curve. The yield curve shows the market’s forecast for what various interest rates will be throughout time.

The swap rate is considered a very important interest rate benchmark to traders. It reflects not only standard rates embedded in the normal yield curve, but also matters related to liquidity, credit risk, and the supply and demand for loan funds of various durations.

For banks, the LIBOR curve is often more important than the US Treasury and other sovereign yield curves. This is because the bulk of corporate loans are tied to the LIBOR rate. Eighty-four percent of US corporate loans are floating-rate with the majority tied to LIBOR and the bulk of those tied to the 3-month USD LIBOR rate. (By comparison, just 3 percent of the US bond market is floating rate.)

When an interest rate swap transaction (trade) is agreed upon, the value of the swap’s fixed rate flows will equal its floating rate payments as denoted by the forward rates curve.

When interest rates relevant to the swap change, investors and traders will adjust the rate they demand to enter into swap transactions. In the graph shown earlier in this section, we can see that there is a spread between the US Treasury rates and the relevant swap rates.

Usually this spread is positive, meaning that market participants demand extra compensation for trading the swaps as opposed to the equivalent government bond of the same maturity.

This is due to the fact there are generally extra risks associated with swaps as opposed to trading the bonds. These include liquidity (i.e., how easy it is to get in and out of a position) and the credit quality of the banks who create these products. Since sovereign governments are commonly regarded as more creditworthy than commercial and investment banks and the government’s bond markets are generally more liquid, the swaps are typically somewhat riskier and generally trade at a slight premium.

However, due to factors related to liquidity, macro prudential regulation, higher capital requirements, high dealer inventories of Treasury debt, restrictions on dealers’ balance sheets, and the swapping activity of companies selling debt to the public, swap rates can actually be lower than the underlying bond.

Hedge funds and other traders would normally arbitrage out any negative swap spread. But because the repo market, used to finance these transactions, consumes more capital for banks that it has in the past (because of regulation) and margins have been compressed on this business segment, hedge funds can no longer rely on repo financing to help facilitate this trade.

Accordingly, we tend to see negative swap spreads at the highest maturities.

How Do Traders Use Swaps?

They are less commonly applied at the day trading level, which trades in and out of positions in minutes or hours. However, “day trading” is nonetheless a loosely applied term. It can also encompass swing trading – which involves holding positions over multiple days or weeks.

A swap represents an interest rate. Interest is the price of credit, or the price of loan funds. (Side note: Interest is not the price of money, as it’s commonly labeled. Money settles payments, while credit is a promise to pay. They are fundamentally distinct sources of capital.)

If the inflation-adjusted interest rate – commonly known as the real interest rate – differs between two countries, then traders will be likely to put more of their money into the country with higher returns (the higher real interest rate).

This means that a strategy some traders will apply is a spread strategy. For example, the inflation-adjusted interest rate on a 10-year US Treasury is currently about 0.8% (3.1% nominal yield minus 2.3% inflation). On a German bund it is about minus-1.9% (0.4% nominal yield minus 2.5% inflation). So a trader may be inclined to capture that 270-basis point (i.e., 2.70%) spread.

These capital flows also influence demand for one country’s currency versus that of another. When capital moves toward USD assets, the dollar increase in value, holding all else equal. Likewise, when capital flows away from euro-denominated assets, the euro decreases in value, holding all else equal, and so forth.

Note that this spread strategy is not foolproof. Prices change. But it is one common strategy.

The Importance of Distinguishing Between Real and Nominal Interest Rates

The higher the expected inflation rate in a country, the more compensation traders will require to hold a particular asset, such as a bond or currency.

Therefore, when looking at bond and swap rates, it is important to distinguish between nominal yield and real yield.

In the US, where inflation is about 2%, a 3% yield on the currency or a bond (a form of longer-duration currency), will generally mean about a 1% real yield. In Turkey, where inflation is regularly high, a 20% yield on the currency or bond might be completely negated by the inflation rate and could result in a negative real yield. Accordingly, traders may be inclined to buy up the US dollar over the Turkish lira when this is in effect.

A straightforward trading principle follows that if inflation-adjusted interest rates decline in a given country, its currency is likely to decline in conjunction. Similarly, if real interest rates increase in a country, its currency is likely to increase in tandem.

The Shape of the Swap Curve

As economies get later into their cycles, yield curves tend to flatten. Many traders make a big deal of this because an inverted yield curve – e.g., the 2-year yield is higher than the 10-year yield – can presage a forthcoming recession.

Why? Because it signals that traders believe that monetary policy has become too tight and the central bank must ease to relieve pressure off the debt servicing burdens in the economy.

Some traders will put more weight on the importance of this curve rather than the corresponding Treasury curve because it reflects not just government credit, but the credit quality of banks.

Moreover, some will put more emphasis on the LIBOR curve than either the standard Treasury curve and its corresponding swap rate curve. (The same goes for non-USD sovereign bonds.) Given that 84% of the US corporate loan market is pegged to LIBOR, this curve is commonly used as the primary benchmark for the pricing and trading of corporate loans and mortgages.

How Do You Make Money on Swaps?

The receiver of the fixed rate portion of a swap makes money when interest rates fall more than what’s priced into the swap or yield curve (and continue to stay that way). This is similar to being long a bond. When interest rates decline, prices increase.

The receiver of the fixed rate portion would lose money when interest rates rise more than what’s priced into the swap or yield curve (and stay higher than expected). The party on the other side of the transaction – the payer – would make money. This is similar to being short a bond. When interest rates increase, prices decrease.

Risks of Investing in Interest Rate Swaps

All fixed income investments involve the same two predominant risks – interest rate risk and credit risk.

The primary risk in swaps on sovereign debt are primarily interest rate related. It is the chief concern of both parties to the contract.

As mentioned, the receiver will profit if interest rates fall and lose if interest rates rise. The payer will profit is interest rates rise and lose if interest rates fall. Given that interest rates constantly fluctuate, there will always be interest rate risk involved.

The credit risk refers to the bank or financial institution defaulting on the contract. This is also commonly known as counterparty risk. Credit risk could also mean the odds of the government defaulting on their debt. For countries like the US and other high credit rating countries, this is unlikely though never entirely out of the question despite the common notion that this debt is “risk free”. Swaps are a higher credit risk instrument than the underlying sovereign bond.

How To Trade Interest Rate Swaps

As a day trader (or trader of any sorts), your use of interest rate swaps would be considered for purposes of “speculation”, or betting on the price movement.

Some traders prefer to buy swaps rather than the underlying instruments because of the embedded leverage inherent in the swap contract. For example, a 2-year deliverable interest rate swap futures (i.e., swap contract on a 2-year Treasury bond, denominated in USD), which goes by the symbol T1U on the ECBOT exchange, the leverage ratio can be around 200 to 1. Intraday and overnight margin are usually different.

For each contract, which is normally worth around $100,000 per contract (depending on the price purchased), the intraday maintenance margin is roughly $500.

The more volatility inherent in the underlying bond, the higher the margin requirements.

For example, trading fed funds futures (ZQ on ECBOT), the embedded leverage can be around 2,000 to 1 or higher, given around $400,000 per contract and a maintenance margin of $100-$200 depending on whether it’s being held intraday or overnight.

On longer duration underlying bonds, such as the 10-year US Treasury, the associated swap contract N1U will have embedded margin of approximately 50x to 60x.

Other Reasons for Owning Interest Rate Swaps

Hedging

Some traders use interest rate swaps to hedge against interest rate exposure or express opinions on the credit market in various forms.

For example, traders who have high credit quality, long duration bonds may want to offset this risk by using swaps. Essentially, swaps are primarily used as a form of insurance.

Shape of the Yield Curve

Some use swaps to make a bet on the future shape of the yield curve. For example, traders who believe that the yield curve is too steep can sell the front end of the curve (expecting rates to increase), buy the back end of the curve (expecting rates to go down), or both.

Other Credit Securities are Unavailable or Unviable to Trade

Swaps can be used as a proxy for other fixed income instruments. Many fixed income markets are relatively illiquid. This is also in part why bonds and other fixed income securities are less popular among day traders relative to equities, currencies, and commodities. Swaps for certain underlying securities are often more liquid markets.

Resolve Asset and Liability Mismatches

For banks and insurance companies, their liabilities are often short-term in nature while their assets (i.e., often mostly loans) are longer-term. When these don’t match, and liabilities come due without sufficient assets to service them, this can cause a solvency issue. To help with the management of assets and liabilities, these entities can help match the duration of assets with the duration of liabilities.

Lock in Financing Long-Term

When companies issue bonds, they will often seek to lock in the rate by entering into swap agreements. Once they’re able to sell these bonds to the investing public, they will sell these swaps. This helps protect against any potential increased financing costs. In the event interest rates go up in the time it took to sell the bonds, the swap contracts will help neutralize this loss.

Align Interest Rate Movements with Their Asset Mix or Business Interests

Some businesses benefit from rising interest rates – e.g., some banks, insurance companies, investment managers. On the other hand, various others benefit from falling interest rates, such as homebuilders, real estate developers, farmers, and other entities that rely on lower borrowing costs.

Some corporations may choose to pay the floating rate and received the fixed rate in order to hedge against falling interest rates. Others may choose to receive the floating rate and pay the fixed rate to hedge against rising interest rates.

Offset Net Interest Rate Exposure

Banks have balance sheets that contain large numbers of loans, investments, and derivatives contracts that will produce some net interest rate exposure. Many of these will offset each other depending on the mix of fixed rate and floating rate assets and liabilities and their durations. A bank’s risk management department will keep tabs on this mix. Any net unwanted interest rate exposure can be offset with interest rate swap agreements.

How to Calculate Swap Rates

Determine the Notional Principal

The hypothetical principal amount that serves as the base for interest calculations.

It’s essential for setting the scale of the swap but does not physically exchange hands.

Identify the Fixed and Floating Rate Specifications

- Fixed Rate – Set at the inception of the swap and remains constant throughout its duration.

- Floating Rate – Usually tied to a benchmark such as SOFR, adjusting at predetermined intervals.

Calculate the Payment Periods

Define the frequency of interest payments, which can be quarterly, semi-annually, or annually, influencing the swap rate computation.

Calculate Fixed Leg Payments

Multiply the notional principal by the fixed rate and adjust based on the payment frequency to determine the payment amount for the fixed leg.

Calculate Floating Leg Payments

Recalculate the floating leg payment for each period based on the current benchmark rate.

Adjust for any spread and the payment frequency.

Netting Off Payments

The exchange of cash flows usually involves the net difference between the fixed and floating leg payments as per the swap agreement.

Swap Rate Determination

Finalize the swap rate based on the calculations and netting off of payments, reflecting the cost or benefit of entering the swap agreement.

Example of How to Calculate Swap Rates

How to calculate 5y5y swap rate based on 5y swap and 10y swap?

Calculating the 5-year forward starting in 5 years (5y5y) swap rate from the 5-year (5y) swap rate and the 10-year (10y) swap rate involves using the concept of forward rate calculations.

The principle behind this calculation is to find a rate that would make an investment in a 5-year swap, 5 years from now, equivalent to the combination of investing in a 5-year swap today and a 10-year swap today.

To simplify, let’s denote:

- R_5_y as the 5-year swap rate,

- R_10_y as the 10-year swap rate,

- R_5_y_5_y as the 5-year forward swap rate starting in 5 years.

The formula to calculate the 5y5y forward rate is derived from the concept that the return of investing in a 5-year swap and then another 5-year swap 5 years later should be equal to the return of investing in a 10-year swap straight away.

This can be expressed as:

(1+R_5_y)^5 × (1+R_5_y_5_y)^5 = (1+R_10_y)^10

From this, you can solve for R_5_y_5_y, the 5-year forward swap rate starting in 5 years.

Rearranging the formula gives:

R_5_y_5_y = ((1+R_10_y)^10 / (1+R_5_y)^5)^(1/5) – 1

It’s important to note that the swap rates (R_5_y, R_10_y, and R_5_y_5_y) should be expressed as decimal equivalents (e.g., 2% as 0.02) when performing these calculations.

Let’s calculate a hypothetical 5y5y forward rate given a 5-year swap rate of 1% (or 0.01) and a 10-year swap rate of 2% (or 0.02):

- Convert the percentages to decimals:

- R_5_y = 0.01

- R_10_y = 0.02

- Plug these values into the formula:

R_5_y_5_y = ((1+0.02)^10 / (1+0.01)^5)^(1/5) – 1

Let’s perform the calculation.

The calculated 5-year forward swap rate starting in 5 years (5y5y) based on a 5-year swap rate of 1% and a 10-year swap rate of 2% is approximately 3.01%.

This means, under these hypothetical rates, the implied interest rate for a 5-year swap starting 5 years from now would be around 3.01%.

If doing this through code (e.g., Python), we can use this:

R_5y = 0.01 R_10y = 0.02 R_5y5y = ((1 + R_10y)**10 / (1 + R_5y)**5)**(1/5) - 1 R_5y5y

Related: How to Calculate Swap Rates

Final Word

Day trading interest rate swaps is not nearly as popular as trading equities, currencies, and commodities. Part of it is the limited access from most brokers. (Certain brokers available to individual investors, such as Interactive Brokers, are an exception.)

But part of it is that interest rate swaps are not as readily understood by the public in the same degree as the asset classes that dominate the coverage in the financial media.

Interest rate swaps, mechanically, are very similar to a bond. Those who have the fixed rate exposure – in regular cases, the buyer of a fixed rate bond – will profit when interest rates decline and lose money when interest rates rise. Those who enter into a swap with the floating rate exposures – normally, the one short-selling a fixed rate bond – will profit when interest rates rise and lose money when interest rates fall.

Many traders prefer to use swaps over bonds because the former are often more liquid. Moreover, swaps normally require only a small initial capital outlay, which can magnify both returns and losses.

Day traders and other investors will use them for speculative purposes to bet on up and down movements or the change in one rate versus another. But they can also serve a central purpose for other entities, such as hedging, risk management, and other corporate finance needs.

Key Highlights

- Interest Rate Swaps Are OTC Derivatives

- They allow the exchange of fixed interest payments for floating rates over a set period.

- Useful for betting on rate changes or hedging financial risks.

- Fixed and Floating Legs

- Swaps involve a fixed rate that remains constant and a floating rate that adjusts according to benchmarks like SOFR.

- Provides flexibility in managing interest rate exposure.

- Market Makers and Fees

- High credit quality banks act as market makers, facilitating swap transactions for a fee, especially for large trades through inter-broker dealers.

- Hedging and Speculation Tool

- Initially designed to offset floating-rate liabilities risks, swaps now also serve traders and investors for speculation and expressing views on interest rate directions.

- Swap Rate Importance

- The fixed rate in a swap, reflecting compensation for floating rate risks, is important for traders as it indicates future interest rate expectations and incorporates factors like liquidity and credit risk.

- Real vs. Nominal Rates

- Traders must differentiate between nominal yields and real yields, adjusted for inflation, to make good decisions, as real yields affect currency value and investment returns.

- Yield Curve Dynamics

- The swap curve’s shape, especially when it flattens or inverts, can signal economic expectations, influencing trading strategies more significantly than government bond yield curves.

- Trading Strategies

- Strategies include spread trading between countries with different real interest rates and using swaps as a proxy for less liquid fixed income markets or to express opinions on the credit market.

- Risks

- Main risks involve interest rate fluctuations and credit risk from the counterparty, with interest rate risk being a primary concern for both parties in a swap agreement.

- Calculating Swap Rates

- Involves understanding notional principal, fixed and floating rate specifications, payment periods, and using these to determine the fixed and floating leg payments, and ultimately, the swap rate.