13 Top Mistakes Traders Make [And How to Avoid Them]

Trading is largely a process of making mistakes and learning from them to get better. Unfortunately, of course, these mistakes can be very costly.

As such, trading can be risky. But risky things are not inherently risky if they’re understood and controlled for.

For example, flying an airplane is very risky if you don’t know what you’re doing. However, it’s a very safe thing to do if you’re trained to do it.

Trading can also be a very safe thing to do if your plan is economically sound. But it can be extremely risky when it’s done in a random and sloppy way.

However, by being aware of the most common mistakes traders make, you can work to avoid them.

Below, we’ve listed the 11 most common mistakes traders make and ways to make sure they don’t impact your trading results.

Key Takeaways – Top Mistakes Traders Make [And How to Avoid Them]

- Don’t panic-sell

- Don’t stay in too much cash

- Don’t try to time the market

- Don’t trade with emotions

- Have a trading plan

- Don’t be overconfident, which can lead to poor decisions

- Don’t “revenge trade” to make up for losses or bad decisions

- Don’t trade too much (overtrade)

- Don’t forget to rebalance

- Don’t use too much leverage (margin)

- Don’t be short gamma

- Don’t proxy trade

- Don’t mistake different positions for diversification

#1 They are short gamma

Why is this #1?

Because overleveraging by being short gamma is one of the most common reasons traders blow up.

Being “short gamma” basically just means being net short options.

Being short gamma on its own is not inherently bad. But it can be very risky and subject you to unlimited loss potential.

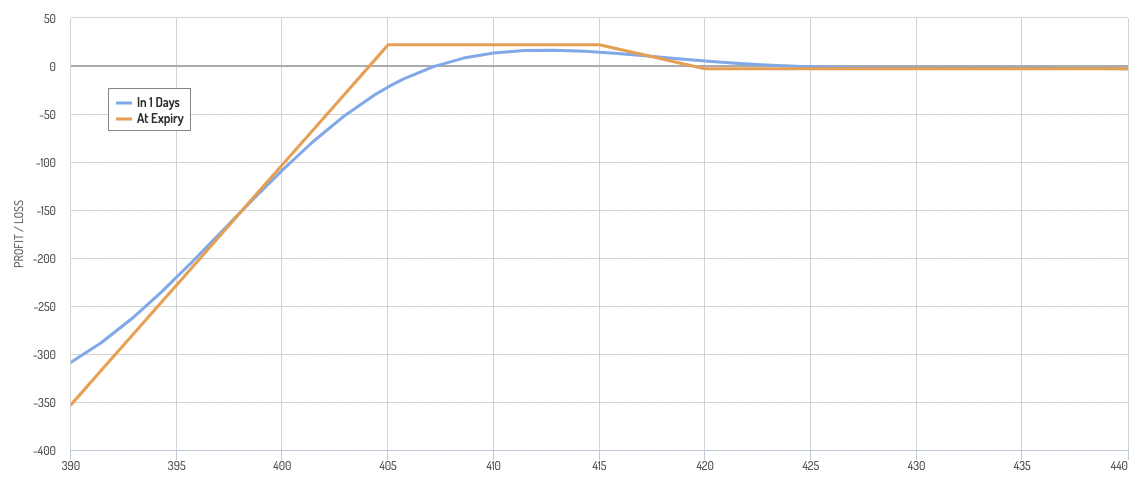

A short gamma strategy often looks like this in terms of an options payoff diagram:

They have a thin layer of profitability, but huge downside.

Short gamma strategies are often attractive because the chance of making money often comes with a very high probability.

However, when they lose money, they often lose a lot.

Selling OTM options

Examples include selling out-of-the-money (OTM) options.

For instance, if you are conditioned to seeing oil being under $100 per barrel, you could think to yourself, “there’s no way oil can climb up to $120 per barrel within the next week or month, so it’s attractive selling 120 calls to capture this premium.”

Except… it can rip higher. A lot higher.

In theory, there is no upper limit to how high an asset can go. Crazy things happen all the time.

If you sold a 120 call on CL futures (WTI crude oil futures) for a $1,000 premium when oil is under $100 per barrel you might think that’s an easy $1,000 you’re about to earn.

But what if oil rips to $150 per barrel? Then you just lost $30,000.

What if it goes to $200? Then you just lost $80,000. And so on.

That $1,000 premium that previously looked extremely juicy and like “easy money” now looks like a minnow in comparison to the losses. That is, if they were to happen. And if you trade long enough, they will happen.

Moreover, options are nonlinear securities. Losses can get worse in a nonlinear way in a hurry.

Dynamic hedging

Even if you think to yourself – “on the off chance this goes higher I can just dynamically hedge to be safe and the premium will be safe.”

But if you choose to do that the asset can easily reverse and you can lose money that way.

In fact, the faster something runs higher, the more likely it is to reverse. That’s why implied volatilities on options – both puts and calls – stay elevated.

So if you dynamically hedged by buying the underlying to protect your premium, then hedged your new position by buying put options, you’re going to be paying a lot.

What you’re paying for the puts could be more than whatever premium you originally expected to receive selling the calls.

And if the puts are OTM, then your potential losses will be there until you hit the strike price before your puts can take over.

Options’ non-linearity

Prices don’t even have to go in-the-money (ITM) for losses on options shorting to stack up. All you need is a partial rip in price or implied volatilities to go higher to lose money.

Then you risk eroding your capital cushion and getting margin calls.

It’s an easy way to lose multiples of the premium you’ll receive from the option buyer.

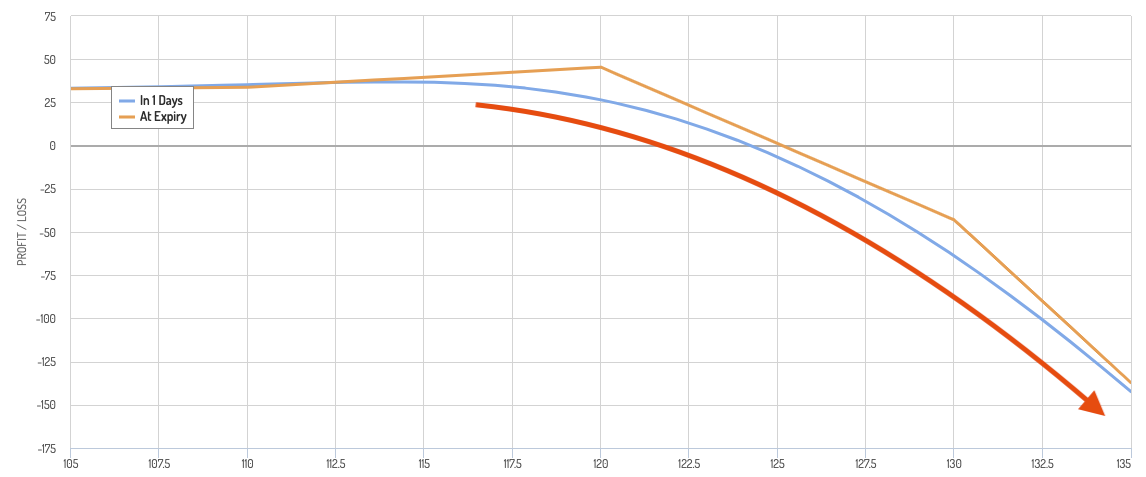

The worst thing about OTM options is you’re short convexity. As they approach ITM they can gain value in an exponential way, and deliver losses to sellers in an exponential way, which makes losses even worse.

What to do instead

We know it’s tempting to be short gamma in order to harvest premium and try to earn that income, but it can be extremely risky.

Some traders believe that portfolios should never be short gamma.

Anyone who’s shorted gamma knows how painful it can be losing many multiples of your premium that you thought might otherwise be a payout you had a high to very high probability of receiving.

If you own options, your losses are limited to the options premium. This can allow you to sleep well at night.

You can go long options to try to capture the upside of – and limit potential losses from – whatever idea you’re trying to express.

That way, when you’re wrong, you should only lose a little bit. When you’re right, you can make a lot.

If you sell options, then your losses could theoretically be unlimited. If a market rips in an unfavorable direction, you could be wiped out.

There’s a saying that goes along the lines of: “If you’re long gamma, you die slowly. If you’re short gamma, you die quickly.”

When traders and investment funds wipe out, it’s generally because of either too much leverage or being short gamma.

If you do sell options, ideally don’t do it in isolation. Have it be covered by having a position in the underlying asset or because it’s part of a broader strategy, such as call spreads, put spreads, iron condors, and so on.

Try to avoid having any tails open – in other words, where a huge move in a certain direction can blow a huge hole in your portfolio or lead to the risk of ruin.

Betting on the most probable outcome isn’t always the best thing to do.

Always follow the concept of expected value when making trading decisions.

Be as objective as possible about your probability of being right or wrong, how much reward or penalty you’ll have for being right or wrong, and being aware of what you don’t know and what can’t be known and being immunized against this to the best extent possible.

#2 Staying in cash

Cash is perceived as a safe investment class because its value doesn’t move around much.

But after adjusting for inflation and any taxes that apply to the interest earned, it’s the worst asset class you can have over time.

What to do instead

Traders who have more cash than their long-term strategy calls for – because they sold when markets were going down or for any other reason, should look to put their money to work.

Dollar-cost averaging is a method where you buy set amounts of assets at regular intervals (say, monthly, based on any money you don’t need right now) to get into the market.

Dollar-cost averaging effectively reduces your portfolio’s sensitivity to the luck of timing.

This can make it easier for more timid traders and investors to move out of cash, since they can avoid the worry of putting their money into the market, only to see what they bought do down in value.

Remember that the biggest determinant to your success is not investment or trading returns, but savings rates. If you save $2,000 per month and get 5 percent returns per year, that’s still better than putting in $200 per month and getting 20 percent returns.

If you’re looking for capital gains potential, stocks have outperformed all other asset classes over time, with cash performing the worst.

#3 Trying to time the market

Even for professional traders and investors, trying to time the market is a fool’s errand.

Lots of things in the financial markets are dependent on other things, so you’ll never get the timing exactly right.

What to do instead

Instead, develop a long-term plan and stick to it. This will help you stay disciplined and not get caught up in short-term swings.

As we mentioned in the section above, dollar-cost averaging is going to be more effective than trying to time tops and bottoms.

#4 Trading with emotions

When trading with emotions, traders often make bad decisions based on fear or greed.

For example, they may sell when the market is going down or buy when it’s going up. This can lead to big losses or gains that never come.

When you trade with emotions it’s easy to buy when things are great and sell when things are terrible.

But this will lead you to do the exact opposite of what you should do.

What to do instead

If you do decide to trade tactically, you’ll be in a game with yourself inasmuch as the markets.

What’s meant by that is you basically have to go opposite your instincts. Buying is painful when markets have fallen a lot but they’re classically the best money-making opportunities.

It also may seem to hurt to sell when markets have gone up a lot. But when assets go up a lot – especially when it’s due to earnings multiple expansion (e.g., P/E ratios going higher), not earnings – it usually means they’re more expensive investments, not more attractive ones.

As the saying goes, “they look more expensive when they go down and look cheaper as they go up.”

Our intuition in the markets with financial assets can often be the opposite of how we treat everyday goods and services.

For example, if we’re considering buying a couch and it goes up in price a lot, we’re less inclined to buy it because it’s more expensive. If it’s on sale and the price is cheap, we’re more likely to buy it.

But if a stock goes up, we often perceive that it’s a better thing to buy rather than a more expensive one. And if it goes down, we may perceive it to be a riskier investment rather than a cheaper one.

Of course, whether an investment or stock is cheap, expensive, or fairly valued will depend on how much it’s earning relative to its price.

A stock trading at $100 per share with $10 in earnings per share (EPS) – a 10x P/E ratio – may be less expensive than when it was trading at $60 with only $4 in EPS – a 15x earnings multiple.

#5 Not having a trading plan

Not having a trading plan is another common mistake traders make.

It sounds like generic, cliched advice, but even the biggest professional investors can get caught off guard by market conditions that blindsided them (e.g., wars, natural disasters, regime changes, and so on).

This can lead to making rash decisions, trading on hunches, and other poor decision-making.

You need to know what you’re going to do ahead of time.

It doesn’t take a lot of time to come up with a good plan.

What to do instead

A trading plan is a set of rules that you create for yourself, which govern how you will trade.

This can include what assets you will trade (stocks, currencies, commodities, etc.), when you will trade them, how much you’ll buy or sell, and your risk management parameters.

It’s important to have a plan so that you’re not making decisions based on emotions or simply not knowing what to do.

The easiest way to minimize the effects of market turbulence is to have a diversified portfolio to help immunize yourself as much as problem from what you don’t know and can’t know.

#6 They’re overconfident, which leads them to make poor decisions

I think we’ve all been guilty of being overconfident about something (trading-related or not).

In the markets, it’s easy to get the risk/reward of a trade very wrong.

Many people overestimate their ability to judge something accurately or are too quick to confidently come up with opinions or come to conclusions that are unlikely to be correct.

We tend to overestimate our own rationality. We also all have blind spots. And we can’t appreciate what we can’t see and how our particular ways of thinking make us blind.

Markets already bake in what’s known

We also have to understand that markets are discounting mechanisms. It’s not whether things are good or bad, but whether they’re good or bad relative to what’s already discounted in the price.

Everything that’s known is in the price. Many individual novice traders tend to bet on what they hear is good or overemphasize what’s done well in the recent past.

Google, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft may be great companies. But what’s known about them is already baked into the prices of their respective stocks.

So they aren’t inherently better bets than other companies in the market even though they seem vastly superior because they’re all worth trillions of dollars in market cap and have done extremely well looking in the rear-view mirror.

Anchoring bias

For example, a trader might see a stock at $100 and see it fall to $80. They think it’s at a huge discount and can’t fall even more.

This is an example of “anchoring” bias.

We’re so accustomed to seeing things a certain way that it’s hard to imagine things a different way.

The stock may have fallen to $80 because expectations of its earning potential are much lower, so the drop in price may actually be justified or even not enough.

After all, markets discount everything that’s known. So assuming that the market is “irrational” and you know better is something that will be borne out by the results of any trades you make.

It’s also possible that the market’s new expectations are still too bullish despite the new lower price.

Lots of “can’t miss” stocks that were impressively hyped up by management teams, the media, their legions of supporters, etc., have been later found out to be massively overpriced or even outright frauds or stock promotions that weren’t really worth anything at all.

That “anchoring” bias could entail having an “anchored” perception of the value of a beaten down company (by the much higher price it used to trade at) when it could still have a lot further to fall.

What to do instead

Have a well-balanced, strategically diversified portfolio that doesn’t involve having to make a lot of tactical bets.

It’s the most reliable way for individual investors, and most professional investors, to make money over time.

#7 They “revenge trade” to make up for losses or bad decisions

It’s a common psychological bias to hate selling an investment at a loss.

This might encourage them to hang onto stocks or assets even if there’s compelling evidence why it might be good to sell (e.g., the company is earning less money, slashed its dividend, etc.).

Moreover, it can be common to cut winners too soon fearing that the assets might fall. In behavioral finance, this is called the “disposition effect”.

What to do instead

Every trade is a business decision.

When you make a bad decision, it’s important to cut your losses as soon as possible and learn from your mistakes.

Don’t let emotions such as regret, revenge, annoyance/anger, etc., get in the way of making logical decisions.

No one has a crystal ball and no one can predict the future with 100 percent certainty.

There’s always going to be some risk when trading. So make sure that any potential trade meets your predetermined risk/reward parameters.

If you do lose money? You can always make it back.

What’s happening right now always seems more important than it will in retrospect. Things can change a lot even in a short period of time, especially as we learn more and get better at things over time.

But an easy way to keep losing money is to continue making bad trades.

#8 They trade too much

It might seem like more trades means more opportunities to make money.

But overtrading can actually lead to poorer decision-making and increased chances of losing money.

There are also transactions costs. Commissions and the cost of getting in and out of trades (because of the bid-ask spread) can add up over time.

Moreover, you will have to consider the tax implications of trading a lot.

Many countries have short-term and long-term capital gains considerations. Long-term capital gains are taxed at lower rates, which is used by governments to incentivize longer term investment.

What to do instead

Only trade when you absolutely need to. Also consider your transaction costs and tax implications.

#9 They forget to rebalance

During a major market selloff in stocks, a portfolio’s asset allocation toward equities tends to decrease substantially. When some assets decline, other assets often increase in value (e.g., bonds, commodities) because every asset class does well in a certain environment.

For example, stocks do well when growth expectations increase and when inflation is low to moderate. Bonds tend to rally when there’s an adverse shock in growth expectations. Commodities tend to rally when inflation expectations run above expectations, and so on.

Often surprised by the move, traders and investors may neglect to rebalance their portfolios back into equities – or whatever asset class that fell in value.

And, as a result, the lack of rebalancing may lengthen the amount of time the portfolio takes to recover from market drawdown.

What to do instead

If you do rebalance a portfolio, try to stick to it.

If you are hands off with your portfolio, it can pay to check periodically.

Rebalancing tends to improve risk-adjusted returns over time, just as long as it doesn’t generate excessive tax and transaction costs.

This will help to reduce the portfolio’s sensitivity to environmental biases and also gets rid of timing considerations.

#10 They use too much leverage (margin)

Leverage is not a black-and-white thing – “any leverage is bad and no leverage is good.”

A portfolio that is well-diversified and well-leveraged can be materially safer than a portfolio that’s heavily concentrated with no leverage.

The problem is when individuals get into portfolios that are heavily concentrated and heavily leveraged.

As they say, leverage is a double-edged sword that can lead to more gains but also terrible losses.

It can even wipe you out entirely.

The very basics of trading entail making sure that the risk of ruin is nil.

Adding too much leverage to a portfolio can make that a very real possibility.

Play offense, but play defense too

Part of trading is figuring out the right balance between offense and defense.

Most beginning traders are too focused on scoring touchdowns and neglect risk management almost entirely, which they inevitably pay the price for.

If you play too much offense, you’ll wipe yourself out. If you play too much defense, you’ll never make any money.

You have to figure out how to strike the right balance. Even experienced professional traders can struggle with this.

What to do instead

Leverage is just a tool that can help you enhance your gains and help you “turn the dial” to a desired risk level.

For example, let’s say you have a portfolio that’s expected to obtain 6 percent returns at 15 percent volatility (unleveraged) and a portfolio that’s expected to obtain 3 percent returns at 4 percent volatility.

If you were to leverage the 3 percent portfolio 2x and there was no interest cost from borrowing (e.g., you used futures or another leverage-like technique such as options strategies), you could have a portfolio expected to yield 6 percent at 8 percent volatility.

That’s the same return for roughly half the volatility of the 6 percent return/15 percent volatility portfolio.

So, from that perspective, it’s more about risk-adjusted returns while making sure that your risk level stays within acceptable parameters.

Make sure your risk of wiping yourself out is negligible. You might choose to do this by owning options, paying a small bit to cut off your left-tail risk entirely.

#11 They panic-sell

Panic-selling is one of the most common mistakes.

It feels better getting out of trades that have gone horribly. But it’s not always the best decision.

What to do instead

Having a great, diversified and well-balanced portfolio will help you to make money and balance the ups and downs over time. It will reduce the odds of downturns, tail risk, and make any underwater periods shorter.

One of the things you can be most sure of over time is that financial assets will outperform cash. This may not always be true with bonds given how yields are in nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) terms, but if you have a diverse assortment of stocks (e.g., individual stocks, stock indices) and other assets from different countries they will probably earn profits provided enough time.

#12 They proxy trade

Proxy trading involves choosing securities or instruments that only approximate the view you’re trying to express.

One example would be buying oil stocks to try to express a bullish view on oil.

The risk is that the correlation isn’t pure.

Another example would be buying gold as a way to express a belief that inflation will rise. But gold is a real rates play, not an inflation play.

What to do instead

Buy the thing that expresses your view directly.

If you think oil will rise, buy oil.

If you think inflation will rise, buy inflation swaps.

If you need to proxy trade, do so as closely as possible. To express a bullish view on inflation you can buy TIPS and short nominal rate bonds of the same duration.

Related: Proxy Trading

#13 They mistake various positions for diversification

Buying a bunch of stocks will only diversify you so far because most stocks are fairly tightly correlated.

Likewise if you buy oil, industrial commodities, and go long the Brazilian real against the US dollar, that is also, in large part a highly correlated set of positions.

What to do instead

Understand what makes positions inherently diversifying. Find assets that not only have different drivers of cash flow, but have different environmental biases.

Related: False Diversification

Conclusion

When it comes to trading, making mistakes is inevitable.

But by knowing what the most common ones are and what to do instead, traders can greatly improve their chances of success.

Remember the tips we talked about in this article, such as having a well-balanced and well-diversified portfolio and these general guidelines:

- Don’t panic-sell

- Don’t have too much cash beyond what your strategy and liquidity needs require

- Don’t try to time the market

- Don’t trade emotionally

- Have a trading plan

- Don’t be overconfident; recognize that we all know little relative to what there is to know

- Don’t “revenge trade” to make up for losses or bad decisions

- Don’t overtrade; separate signal from noise

- Don’t forget to rebalance

- Don’t use too much leverage (margin)

- Don’t be short gamma

- Don’t proxy trade

- Don’t mistake different positions for diversification

If you can stick to these guidelines, you’ll be on your way to avoiding costly mistakes, which is a big component of going on to becoming a successful trader.

A lot of trading isn’t about doing anything brilliant, but avoiding doing things that are foolish.