What’s Behind the Rise of SPACs, Cryptocurrencies, and NFTs?

The rise behind high-flying assets like SPACs (blank check companies), cryptocurrencies, and NFTs is related to the environment we’re in and the large-scale liquidity that has caused a rise in all asset classes.

Interest rates in an economy are a function of nominal growth rates.

In Western economies (the United States, developed Europe, and Japan), low nominal growth rates are a function of lower productivity growth rates and low to non-existent (or declining) growth in their working populations.

Real GDP is a mechanical function of productivity growth and labor force growth. Nominal GDP adds in inflation, which is the pricing of economic activity. Inflation is predominantly caused by the demand for something in excess of its supply – i.e., labor, commodities and raw materials, and/or financial assets.

If nominal growth is at a certain weak level, nominal interest rates need to be below that; otherwise, the debt will grow faster than the economy. (This is oversimplifying, as keeping debt servicing requirements in line with or below incomes is most important).

Because of the secular stagnation issues in the West, and the blowing out of these economies’ fiscal balance sheets in 2020-21, this led to a need to lower short-term interest rates and also long-term interest rates through the buying of financial assets (QE). These are the two main forms of monetary policy.

When you can no longer cut interest rates or close risk premiums much through asset buying, you move into a world where fiscal and monetary policy are increasingly unified.

More of the decision-making process falls onto the politicians (the fiscal side) with the central bank supporting that spending.

Politicians increasingly decide where that money and credit is going to go and the central bank funds those initiatives.

There are three basic areas where all this liquidity goes:

- Spending

- Savings and reserves

- Purchases of financial assets

When central banks push the yields on cash and safe bonds down to zero or around zero, they make them yield negatively in real terms.

That means if you lock up your wealth in those, you’re effectively destroying it.

People don’t want to do that, so all that money and credit spills into other forms of assets, including:

- Equities

- Gold and various forms of precious metals (e.g., silver, platinum)

- Commodities

- Other countries and currencies with better yields

- Inflation-linked bonds (e.g., TIPS)

- Real estate

- Art, collectibles, and other real assets

- Private businesses

- New types of assets

These new types of assets are things that you see today like cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and blank check companies.

Cryptocurrencies and NFTs can be considered a type of alternative store of value.

When cash and bonds destroy your wealth and stocks begin to bend down to those types of low yields as well (and provide ample volatility), people become starved for sources to get a good return on their investment.

A lot of that’s spilled out into highly speculative assets, sectors, and newer types of asset classes.

Many blank check companies are used as a form of regulatory arbitrage. It’s easier to take a company public.

And because the demand for financial assets is higher than the supply when policy is easy, it’s been fairly easy to get capital to spill into these SPACs.

They’ve become some of the most popular assets in the markets. The business models of the companies that go public through SPACs tend to be more speculative (e.g., electric vehicles, tech) and don’t have strong operational or financial histories. Companies can sell dreams instead of earnings.

Naturally, the hottest assets tend to be the riskiest and often attract buyers in on leverage, which exacerbates the problem when bubbles deflate or pop.

Everything boils down to interest rates

Everything with a financial nature to it is priced off an interest rate.

This goes for all financial assets. It goes for bonds, stocks, and follows through into private equity, real estate, and everything else.

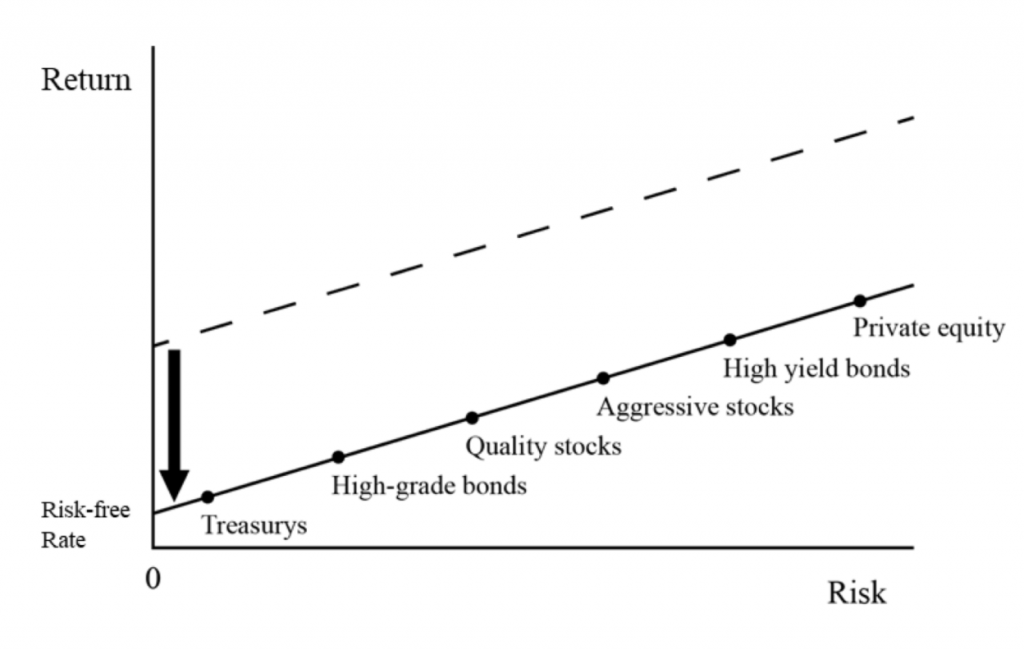

When the yields on cash and bonds collapse, everything else follows. People still need returns and will go up the risk ladder to capture the types of returns they need, even if it means lower absolute returns.

Low rates drop the forward returns of all assets

The problem for pension funds

Pension funds in the US, for example, commonly need around 7 percent annual returns to meet their obligations.

Yet if stocks are trading at 25x forward earnings, the inverse of that is the yield (about 4 percent). No asset gets them that 7 percent.

That means they’re possibly faced with a choice between:

- Venturing into leveraged forms of equity

- Requiring bigger contributions from those who pay in

- Sticking to their strategies and not getting the returns needed

None of these are attractive.

The first threatens their viability.

The second is difficult to do and highly unpopular as you have to take more from people in the present. It’s essentially like a tax increase.

The third is unlikely. While markets can outperform or underperform nominal economic activity over the short-run, it’s not likely over the long term.

High inflation can undermine asset values

At the same time, what’s good for the economy is not always good for markets.

As economic growth improves and inflationary pressures show up, central banks will consider pulling back on the stimulus measures that aid financial and real asset values.

The rally in risky assets depends on whether the Fed (the world’s most prominent central bank) bumps into constraints.

These constraints include a few things:

- Inflation (utilization rates bump into capacity)

- Currency depreciation

- Bond sell-off

Inflation in goods and services tells policymakers there is too much money and credit chasing too few things. So they typically want to rein this in by hiking interest rates to control credit growth.

Financial assets use a discount rate to determine their prices. If the rate on cash goes up, that raises the discount rate at which the present value of future cash flows is calculated, reducing their prices, holding all else equal.

In the current environment, a lot of money and credit is being produced. But if that doesn’t go into productivity growth – ideally productivity that’s broad-based – then you’re going to have an issue with currency devaluation.

This feeds into inflation, which can be for various reasons:

- exports are less expensive

- imports are more expensive

- more demand for labor, commodities, raw materials, and/or financial assets relative to supply

It can undermine capital formation by people wanting to get out of certain financial assets that aren’t going to be good stores of value (i.e., they won’t at least hold their value).

Some people realize that with bonds not yielding much (or anything) and all the money printing going on that bonds are a bad investment when they yield negatively in real terms.

Part of having a reserve currency is having a bond market that gives favorable returns to the people you sell it to, while also allowing creditworthy entities within that country to borrow cheap enough to make productive investments.

When a country is essentially addicted to negative real interest rates because of its intractable financial situation, then it puts its bond market at risk of a decline in prices, and its currency at risk of depreciation.

This creates pressure on yields. If the free-market buyer wants them less and less, then the central bank has to print money and buy them.

You get the pressure in yields first, producing a bear market in long-end bonds. Policymakers use that as a signal that they need to be more careful with yields. If the situation gets bad enough they’ll buy them, even going so far as to institute a form of yield curve control.

Higher yields also hit the values of certain companies. Stocks that have the longest durations – most of their earnings are expected to come furthest out in the future – are the most prone to getting hit.

This includes companies like Netflix, AMD, Nvidia, and Tesla. Their high prices are largely a reflection of expectations far out in the future rather than any level of current earnings.

Their valuations are supported through low interest rates.

If you take the low rates away and there’s not much cash flow supporting the valuation, you can expect steep drops in their valuations.

SPACs, cryptocurrencies, and NFTs and how they fit into this picture

The boom in SPACs, cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, and NFTs follows the same type of liquidity wave created by the easy monetary policy from the Fed and ample stimulus provided by the fiscal side (Congress and President).

Fed policymakers can welcome a rise in yields when there’s a boost in the US economy.

But traders and investors can have trouble with this environment. Everyone is typically leveraged long, and that’s underpinned by low interest rates.

When there isn’t much more that interest rates can decline and technically no limit to how much they can rise, that can be an issue.

Even if the Fed controls rates from going higher, it can cause inflation to run hot, and impact bond maturities they don’t directly control while decreasing inflation-adjusted asset values at the same time.

It can also come at the cost of currency devaluation. People pay a lot of attention to whether their assets are moving up or down but not a lot of attention to what their currency is doing.

And these trade-offs are made even more acute when money is leaving the country.

This is because these capital inflows can be used to increase foreign exchange reserves, lower interest rates while producing less inflation, and/or appreciate the currency, depending on how the central bank chooses to use this advantage.

So, central banks have a choice to make between preventing the bond yields from going up or letting it go, or doing yield curve control and risking the currency.

When you have a reserve currency, it’s less painful to do the latter.

Timing for trading purposes

In terms of timing for traders, the bond yields rise before the currency falls.

Rising yields are good for a currency but bad for bonds. Once the yields start giving risk assets a problem, policymakers know there will be an eventual feed-through into the real economy. So they’ll be inclined to print money and weaken the currency to keep a lid on bonds.

From a policy standpoint

But either way it’s bad for you from a policy perspective.

Either the bond yields increases and credit costs rise and asset prices decline (holding all else equal) or the currency goes down.

Foreign investors are already less inclined to buy and hold Treasuries.

Passive investing

Passive investing is another part of the equation, as it’s pervasive. Index funds are a broadly positive force as it gives wide exposure to asset classes at a cheap price.

However, with low interest rates giving very few alternatives to equities as ways to preserve and grow wealth, index funds are paying increasingly higher prices for investments that have lower future returns.

When assets are going higher and higher it feels good, but if there’s not much cash flow underpinning those valuations, then how robust is the asset? It creates a lot of risk if there’s nothing underneath it.

If you can sell the asset to another person you can benefit, but it’s like a greater fool game.

Because of the performance of the past, most investors are expecting much higher returns – especially in real terms – than they’re likely to get. This includes both individual and institutional investors.

It’s true for most asset classes that have gone up in the recent past. They tend to be overemphasized. This gets baked into the price.

And these prices reflect an increasingly optimistic view of the future based on a set of conditions relevant to the past that can actually make it more likely to underperform than overperform.