Options Strategies for Income

Options strategies can provide income through various means, such as selling premium, hedging, or through market movements. These strategies try to efficiently balance risk and reward and offer consistent income while managing potential losses.

Options strategies for income generally entail concepts such as the covered call and other “covered” concepts involving some combination of having a net position in the shares and options written against it (e.g., short calls if long or short puts if short).

A trader or investor might try to squeeze more income out of a stock position by writing calls against it. Additional upside is foregone in exchange for the premium.

In other articles, we’ve written that the covered call – and capturing the volatility risk premium more generally – can be a quality source of alpha generation.

We have other articles on the covered call trade structure, so we won’t rehash too much within this one.

Here we’d like to focus more on not only option income strategies, but also on convex trade structuring.

Key Takeaways – Options Strategies for Income

- These strategies look to balance risk and reward to provide consistent income while managing potential losses.

- Covered Call Writing – Generate income from selling call options against owned stock.

- Put Selling (Cash-Secured or Naked) – Earn premiums by selling put options, with the choice between cash-secured and naked.

- Iron Condor – Profit from the asset’s price staying within a range. Limited risk determined by the strike prices and received premium.

- Modified Iron Condor – A variation of the covered call that includes additional options for improved income and risk management.

- Dividend Capture with Options – Buy stocks before the ex-dividend date and sell call options to earn dividends and premiums.

- Bull Put Spread – Generate income with a bullish outlook. Sell a put option at a higher strike price and buy one at a lower strike.

- Bear Call Spread – Create income in a bearish or stable market by selling a call option at a lower strike and buying one at a higher strike.

- Advanced Trade Structuring – Enhance returns relative to risk through tailored trade structures. Customized strategies can include dynamic hedging and strategic option placements.

- ‘The Option Wall’ Strategy – Limit downside risk while earning premium income, requiring active management and dynamic hedging.

- Volatility Risk Premium (VRP) Strategy – Capture the premium difference between implied and realized volatility, typically through selling covered calls or puts within a risk parity portfolio framework.

- Wheeling Strategy – Sell a cash-secured put on a stock or asset you wish to own. If unassigned, keep the premium. If assigned, sell a covered call.

- Some are more advanced than others.

- Traders should consider their risk tolerance, market outlook, and the specific mechanics of each strategy to effectively generate income through options trading.

Convexity

Convexity in trading refers to a situation where your potential reward is higher than your loss. Oftentimes, a convex trade means one that makes money in a non-linear way when the delta (price) goes in your favor, holding all else equal.

Owning a call option is the most common form of convexity. You pay a fixed premium for very high to unlimited upside.

Convexity can also mean other things.

Building a balanced portfolio that can do well in any economic environment is an example of a convex outcome. You’re limiting your downside by not having a concentrated portfolio while still having quality upside.

Trade structuring can add another layer of convexity. Risk management can add another.

Covered Call Writing

A covered call involves selling call options against a stock that is already owned.

Objective

Generate income from option premiums with an obligation to sell the stock at the strike price if exercised.

Risk Management

Losses can occur if the stock price declines by more than the premium, but this is offset by the premium received.

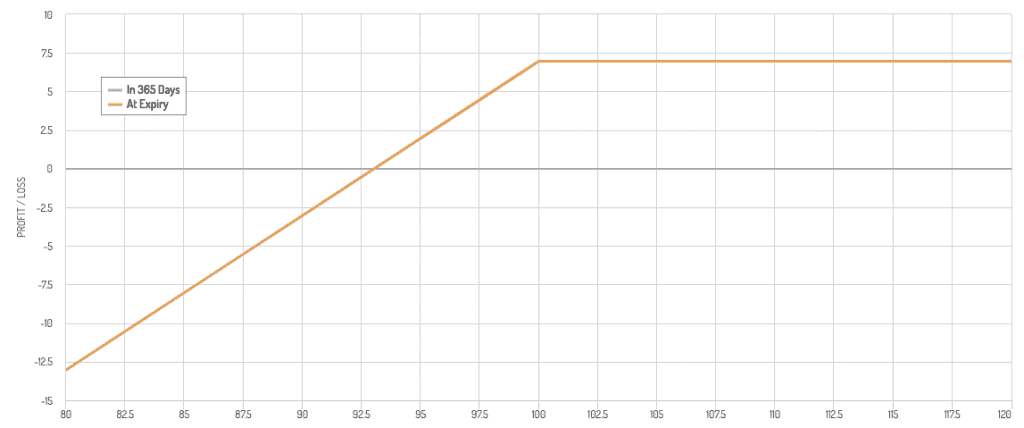

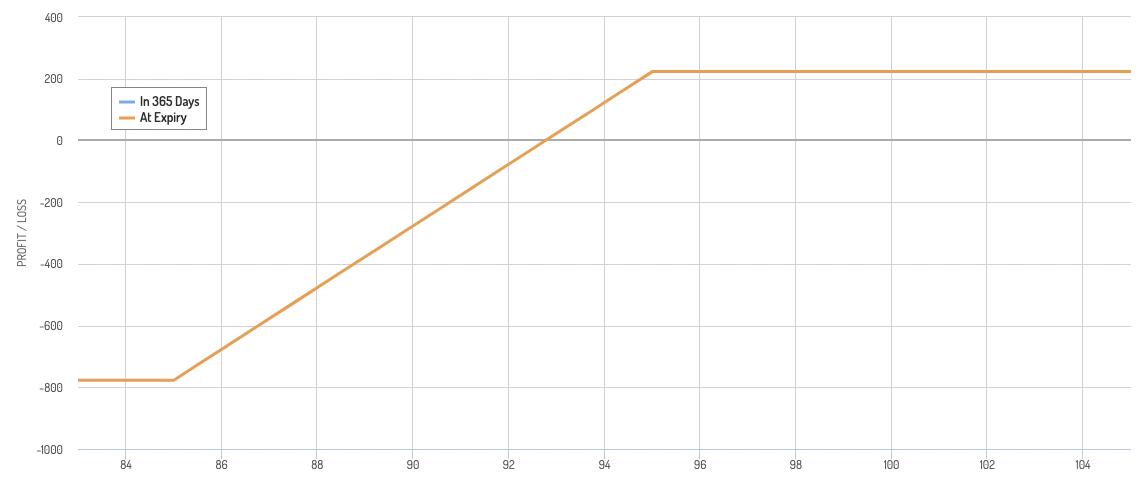

Payoff Diagram

A payoff diagram of a covered call looks like so:

Improving the Covered Call

The covered call has been shown to have a better risk-adjusted return over time relative to simply owning a stock.

If the stock falls, part (or all) of your loss is offset by the premium received from selling the option.

But you’re also exposed. If the stock goes up a lot, you don’t gain in the traditional way because your upside is capped by the option. If the stock goes down, the premium from the call option will only offset so much.

Put Selling (Cash-Secured or Naked)

Cash-Secured Put Selling

Description

Selling put options while setting aside cash to buy the stock if the option is exercised.

Objective

Earn premiums with the willingness to purchase the stock at a lower price.

Risk Management

Potential obligation to buy the stock at the strike price, so it requires cash reserves.

Naked Put Selling

Description

Selling put options without cash set aside for potential stock purchase.

Many traders use put selling with the intention of “if a stock falls to $__ I would buy it there anyway.”

So some consider it an “earn while waiting” type of strategy.

It needs to be balanced against the benefits of simply buying/owning the stock right now.

Objective

Income through premiums with more risk.

Risk Management

Higher risk as it requires buying the stock at the strike price if exercised, without reserved cash.

Payoff Diagram

The payoff diagram looks very similar to that of a covered call.

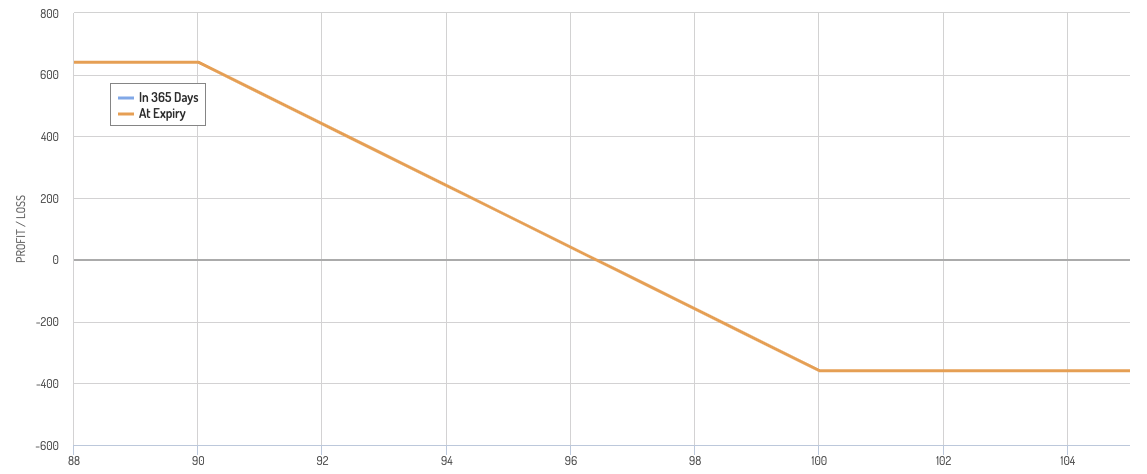

Iron Condor: Basics and Pros & Cons

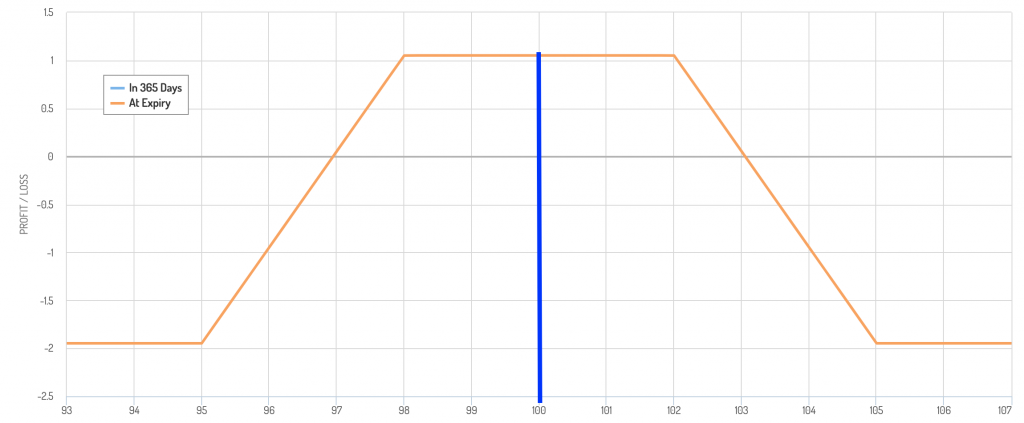

A combination of selling a put spread and a call spread, with both having the same expiration date.

A traditional iron condor involves selling a put option and a call option that are close to the price of the underlying and buying a put option and call option that are further out-of-the-money (OTM).

It creates a trade structure that profits when price remains within a certain range and loses money when price moves outside of it (though a capped amount).

Objective

Profit from the underlying asset’s price staying within a specific range.

Risk Management

Limited risk to the difference between the strike prices minus the net premium received.

Payoff Diagram

The payoff diagram of an iron condor looks like the following below. The blue line denotes the price of the underlying.

Is the iron condor a short volatility trade?

Some call it a short volatility position (which it is if delta hedged in a dynamic way). But without dynamic hedging it relies on price remaining within a certain range by expiration, which can happen with or without a lot of volatility.

The iron condor is a quality trade structure in theory.

Your highest probability outcome is making a profit since you capture the positive profit distribution that’s nearest where price currently is.

You also don’t lose much if price falls outside that range. Being long an OTM call and put option cuts off the tail risk of a big move in the underlying.

Covered call -> Modified iron condor

You can convert a covered call into a modified iron condor. As mentioned, the drawbacks to the traditional covered call is that your downside isn’t covered. You get a little bit from the call option premium but you can potentially lose a lot.

This usually means you’ll have to limit your position size.

If you do run a position that’s concentrated enough such that an adverse enough move could blow a large hole in your portfolio, you’ll probably to prudently hedge against it. This is usually done with options or by have an inverse exposure to something that’s the same or very similar.

The covered call to modified condor occurs by doing the following:

- Owning the underlying

- Shorting a call option (ATM, slightly OTM, or even slightly ITM)

- Shorting a second call option OTM

- Buying a put option

- Buying a call option that’s more OTM than the second call option (optional)

Instead of the underlying price being near the middle of the maximum profit range – like in a typical iron condor – it’s near the beginning.

Shorting the second call option gives the downsloping right leg of the structure. It helps increase the potential profit of the overall trade.

This also opens up potential risk in case the price of the underlying increases beyond the strike price of the second call option.

This can be managed through either:

- i) dynamic hedging (going long additional shares if price gets to that point) or

- ii) by buying an OTM call option to cap your risk.

The second option would give the trade a structure an essentially equivalent look to the iron condor.

The main difference is that the traditional condor doesn’t make use of positions in the underlying asset (unless the trader is looking to dynamically hedge for a particular purpose – e.g., to hedge delta or gamma).

Dividend Capture with Options (Form of a Covered Call)

Buying stocks before the ex-dividend date and selling call options against them.

Objective

Earn dividends and option premiums.

The idea is that the stock falls on the ex-dividend date (by the amount of the dividend per share, all else equal).

So selling a call option can potentially harvest some premium and lose less from the stock’s expected fall on the ex-dividend date.

Risk Management

The stock may fall in price or the call may be exercised, requiring stock sale at the strike price.

Bull Put Spread (Put Credit Spread)

Selling a put option with a higher strike price and buying another put with a lower strike price.

Objective

Income from premiums with a bullish market outlook.

Risk Management

Losses are capped to the difference between strikes minus the net premium.

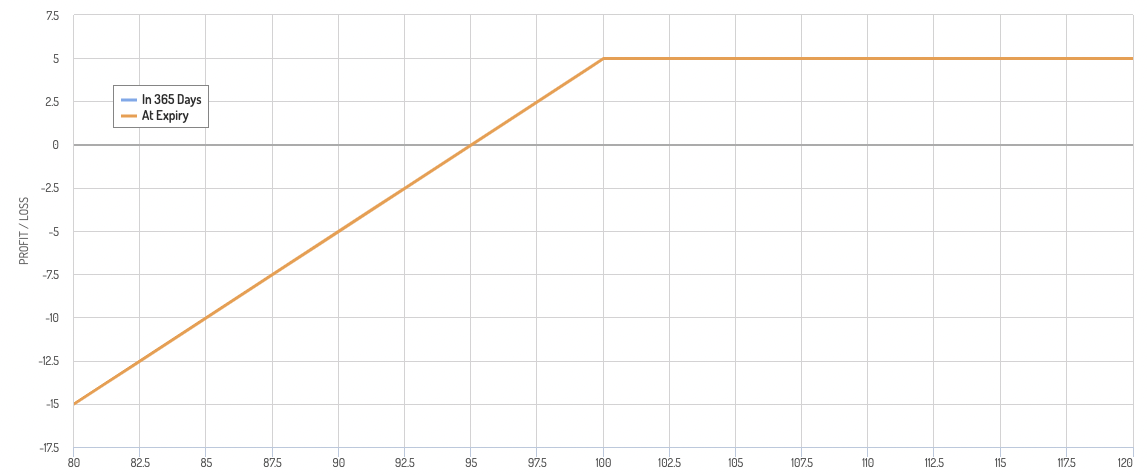

Payoff Diagram

Like a covered call but with limitations on the loss that can be incurred.

Bear Call Spread

Selling a call option with a lower strike price and buying another call with a higher strike price.

Objective

Generate income in a bearish or neutral market.

Risk Management

Maximum loss is limited to the difference between strike prices minus the premium received.

Payoff Diagram

The diagram has a bearish structure, with gains and losses limited.

Advanced techniques

Any trade structure doesn’t have to be “by the book”. There are various ways you can express what you’d like to express without conforming to any given textbook example.

It is, however, important to be able to measure what you’re doing.

There are other tweaks that can be made to increase the return relative to the risk over certain price ranges, by overweighting the short side, by playing with the duration, or potentially shorting the call options of something that’s correlated.

For example, let’s say you wanted to go long 1% OTM SPY calls and short 2% OTM SPY calls to form a bull spread on the S&P 500.

If you just own 1% OTM calls, you maximize your upside but it comes at a heavy cost. Being just one percent OTM, that’s a relatively expensive trade.

By shorting two percent OTM calls, you cap your upside but receive premium to help at least partially offset the costs of going long the calls.

Increasing duration on the short side

To increase this premium you can short a longer maturity relative to the long calls.

If the long calls have 3 days to expiration, you can short calls with 5 days to expiration.

This creates a duration mismatch, so there’s risk involved.

You can also short another block of longer duration calls that are further OTM, such as 5% OTM calls that are 20 days to expiration.

Overweighting the short side

You can also overweight the short side of the trade to get extra premium.

If you bought 20 long calls, you can short 25 short calls. This creates risk when the short calls go ITM. That may have to be dynamically hedged by buying the underlying (or by owning further OTM calls to cap the risk).

But it also means you successfully captured the distribution between the two maturities.

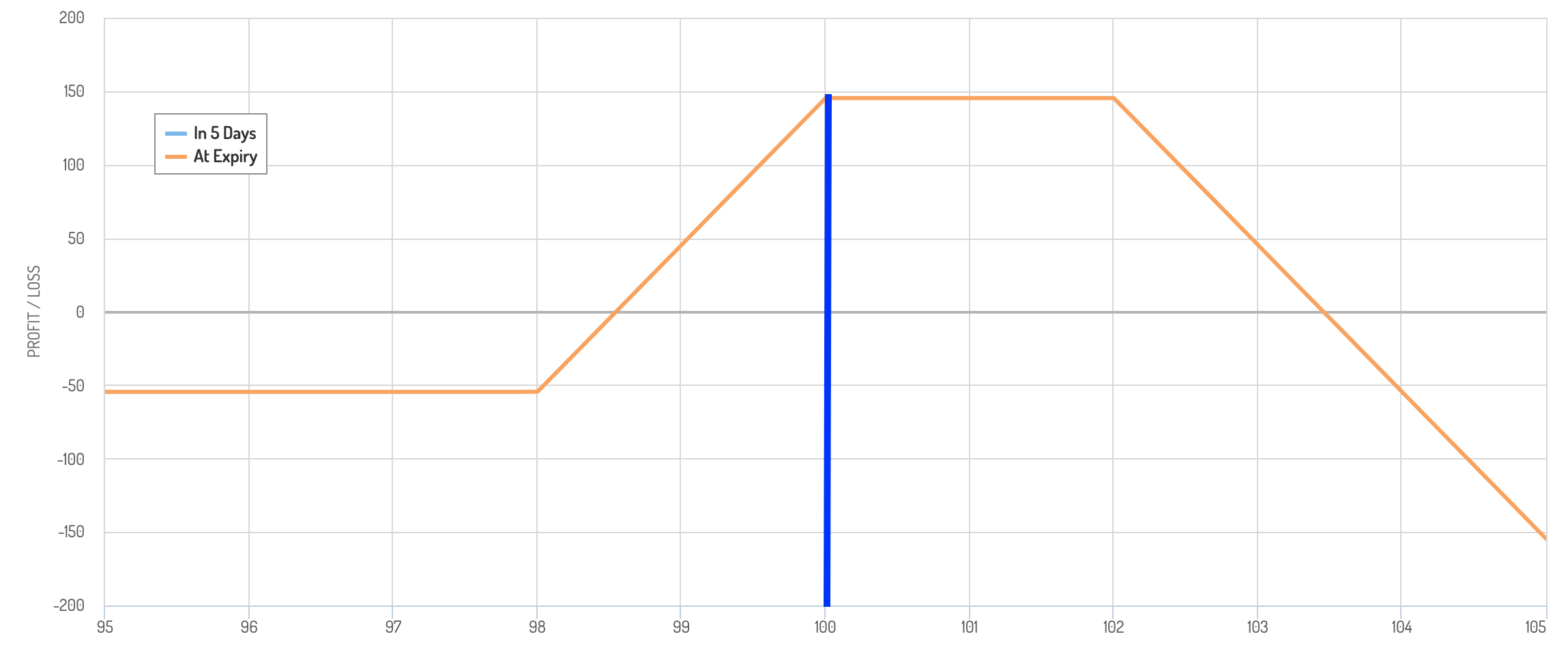

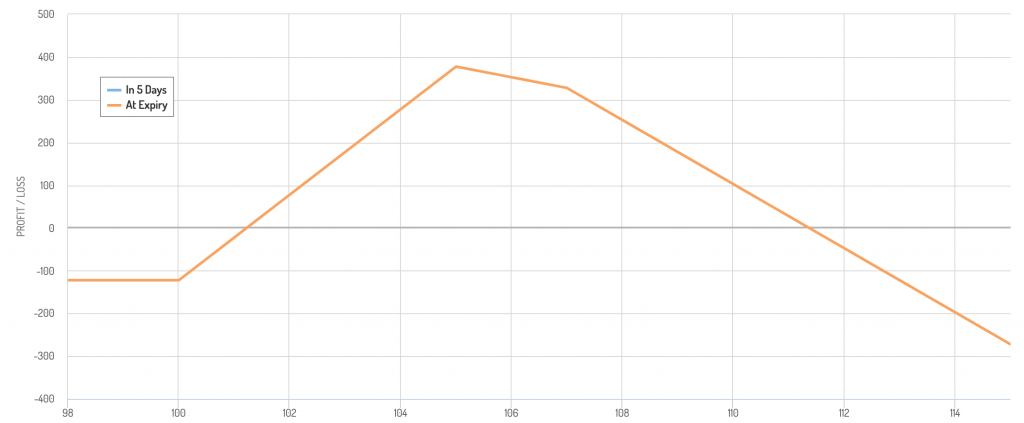

Example

Let’s say the price of the underlying is 100.

You buy 100-strike calls and short a 25 percent higher quantity of 105-strike calls of the same duration.

To increase the convexity of your trade, you short 107 calls of half the quantity of the 100-strike calls.

Trade:

- Buy 100 100-strike calls

- Short 125 105-strike calls

- Short 50 107-strike calls

Your profit diagram would look something like this:

You maximum profit is nearly 4x your potential loss.

If the trade goes very well and you capture all that P/L distribution from 100 to 105, you can dynamically hedge by buying the underlying to avoid the downslope. At the same time, you can buy puts to help lock-in some of the gains.

Trading is all about reward relative to the risk. If the trade goes against you, you lose a little bit. If it goes in your favor, you can make multiples of the total outlay.

If you can tie in such trade structure within the context of a well-balanced portfolio and the risk management is done well, you should make money over time.

‘The Option Wall’

Trading is a game of trade-offs.

If you buy options, you limit your risk but pay a premium that can be very expensive. You not only need a favorable move, but also need enough of a move to be profitable.

Only the underlying avoids this expense, but your exposure is linear. You start making money right away if it goes in your favor, but it also bears all the downside, unlike an option.

The “option wall” strategy is one way to limit your risk and keep the high upside – at least at first.

It involves:

- Buying the underlying

- Buying a put option to limit downside

- Shorting a call option

- Shorting a “wall” of OTM call options to collect premium

The “wall” simply refers to a bunch of call options (or put options for a bearish trade structure) that would need to be dynamically hedged if the underlying gets to that strike price.

If not, it would essentially flip into being short the underlying if it goes past the strike price, which may or may not be desired.

Traders might be willing to take on that risk because if they encounter the necessity to dynamically hedge it means they just made quality money on the trade.

If the underlying goes against them or doesn’t move too much from the strike price, then all the premium from the short call options will work in their favor.

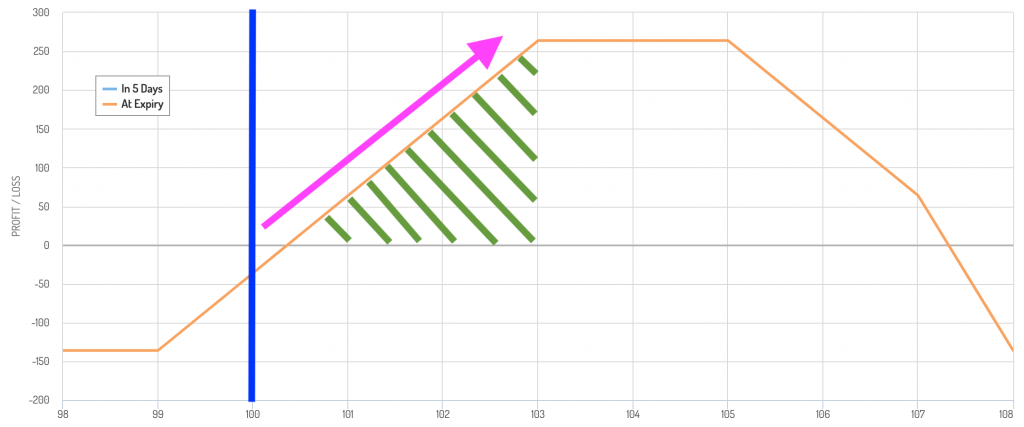

Example

Let’s say a stock is trading at $100 per share. The trader buys the underlying. He also buys a 99 put to limit downside.

He also shorts a 103 call, 105 call, and 107 call (the “wall”).

The payoff diagram is as follows:

Because of the short calls, it takes very little of a move in the underlying for him to be profitable (just past the strike price).

The trade maximizes its profit from the 103-105 range.

Past 105 it’s still profitable but less so because the short call will start losing money. It’s at this point that the trade will be incentivized to go long additional shares to dynamically hedge.

He won’t complain too much about this because he already made money on the trade.

Of course, by buying more shares, that introduces downside if the stock begins declining in value.

To protect profits, he can now buy a 103 put. If he wants to offset or partially offset the cost of the put, he can sell another call.

This would need to be actively managed until the options expire. Because the underlying is covered by the options, typically the whole position is neutralized.

If the trader owns the underlying and the options are OTM, he can set up the same “option wall” trade structure for a future maturity.

Risks to the ‘option wall’ strategy

Active management

The option wall strategy needs to be actively managed. If the underlying goes too much in your favor, it can be bad.

Because dynamic hedging may often be necessary, you need a way to monitor how your positions are doing. It’s very much a day trading strategy.

Collateral requirements

Dynamic hedging requires collateral. Every time you dynamically hedge to add to a position you’re using more of your balance sheet.

You always want to keep a safe capital cushion. You can’t dynamically add shares and sell additional OTM options ad infinitum to repeat the process over and over again. You’ll need to have hard limits.

Yield enhancements to the option wall strategy

A trader can do various things to increase the potential income generation from the option wall strategy.

Forgo the purchase of a put option

Not buying a put option will save you money but open you up to potential downside. Buying protection helps improve the stability of a portfolio. It can also allow you to pursue more concentrated positions than you’d be able to otherwise.

Buy partial protection

Options can be expensive. A rigorous study of the subject demonstrated that buying options as insurance reduces one’s Sharpe ratio over long time horizons.

In other words, the benefit they provide don’t compensate for their price over long time horizons. (They can provide great benefit over shorter time horizons due to the timing element.)

If you’re running a position at 25 percent of your total overall portfolio’s value, if it lost 20 percent, that means five percent (.25*.20) of your account equity is gone.

However, you don’t necessarily need to fork over the cost to hedge the whole thing. If the position was just 5 percent of your total portfolio’s value and it lost 20 percent, you’d lose a more reasonable one percent of your account equity.

Accordingly, you could decide to hedge four-fifths of it rather than the full amount.

Get your short options closer to at-the-money (ATM)

If your first option is ATM, you get a higher premium. Your “wall” of additional short options can also be somewhat closer to ATM, but that means if you get a favorable move you might have to begin your dynamic hedging process sooner.

Selling put options at prices you’d like to buy

Say you’d like to buy the S&P 500 at a certain price lower than it is currently.

You can get paid to wait by shorting put options on SPY (or another instrument based off the S&P 500).

This gives you the chance to derive income while waiting. If it never gets down to your price, you keep the full premium.

Many traders and investors like the idea of selling put options on certain stocks given they get to pick a price they think would represent great value.

Maybe you don’t like Apple stock at its current price, but you’d be willing to buy it if it was 20 percent lower.

The longer the duration of the option, the more premium you get to collect.

If you take a put option with the following characteristics:

- implied volatility of 30 percent

- option duration of one year

- strike price about 20 percent lower than the current price…

…you can derive around a 5 percent premium (in relation to the purchase price dictated by the strike).

Risks to selling put options

The main risk to this strategy is that you can certainly lose many multiples of your premium if the stock declines enough.

Generally the idea behind shorting puts is that you would have bought the stock at this price anyway.

However, things can change between when you made the decision and when the option expires. If a company’s fundamentals have deteriorated, buying at that price may no longer be attractive. You might no longer want to buy the stock at any price.

Moreover, as the option becomes pricier – the trade goes against you if you’re short – it will typically require you to hold more collateral against the position.

As you lose money, your margin requirements increase so you get squeezed both ways.

This is why short puts are often considered “cash secured” puts. If your strike price is $100 on a short put, that might obligate you to buy $10,000 worth of stock per contract (each contract contains 100 shares).

If you have $10,000 in collateral set aside for this, it’s not a problem. But most enter these trades with a margin account that requires significantly less margin than this.

Options are convex instruments, so when the trade goes against you, you will often lose money in a non-linear way. Collateral requirements may increase in the same fashion.

Also, if you are short puts on a non-equity instrument, there’s the potential that you could theoretically lose more than you anticipate.

For example, oil and other commodities can go negative. It means that producers will pay buyers to take it off their hands. This was the case temporarily in 2020.

Those who shorted oil put options at very low positive numbers likely thought that their downside was very little and perhaps capped at a minimum price of around zero or a bit above.

However, during special events, there may be a time where it could make sense for a producer to pay people to take the oil rather than incurring the cost to shut-in production.

Volatility Risk Premium Strategy in a Risk Parity Format

Concept Overview

Volatility Risk Premium (VRP)

Refers to the difference between the implied volatility (market expectations of future volatility) and the realized volatility (actual market volatility).

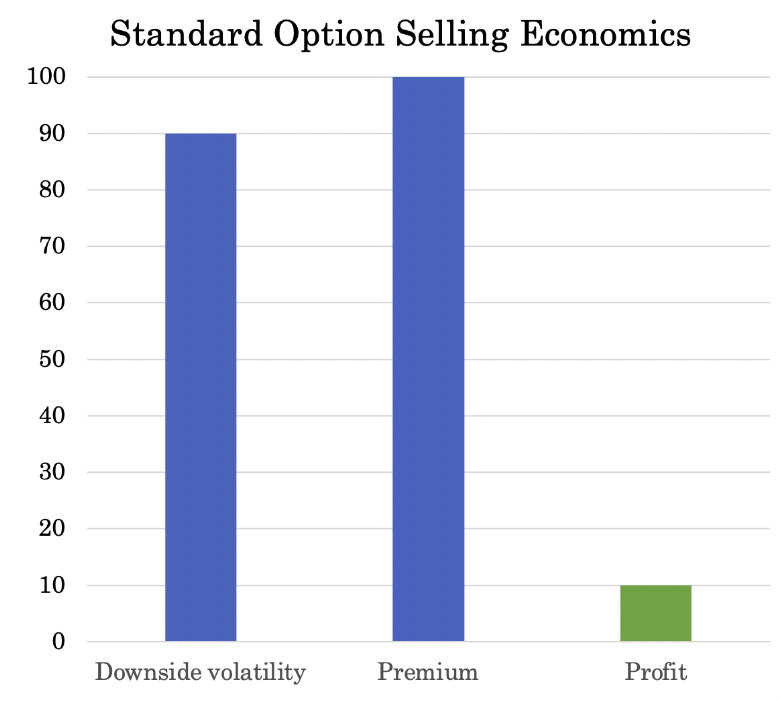

Traders can capture this premium by selling covered calls (typically on index options) across their portfolio and profiting from the tendency of implied volatility to overestimate future realized volatility and the sum of the options premiums being greater than any losses incurred (downside volatility).

Related: Balanced Portfolio with VRP Overlay

Risk Parity

An investment/trading approach that allocates capital across various assets based on risk contributions rather than capital.

The goal is to achieve diversification by balancing the portfolio’s risk across different asset classes, economic environments, or strategies.

Structuring a VRP Strategy in a Risk Parity Framework

A short overview:

Risk Assessment and Allocation

- Evaluate the historical volatility and risk characteristics of the VRP strategy.

- Allocate capital to the VRP strategy so that its risk contribution is equal to other components in the portfolio.

Incorporation into a Diversified Portfolio

- Combine the VRP strategy with other asset classes like equities, bonds, commodities, and alternative investments.

- Adjust the allocation to each asset class so that each contributes equally to the overall portfolio risk.

Execution of VRP Strategy

Option Selling

- Implement the VRP component by selling at-the-money or out-of-the-money options, such as puts or calls, on major indices or ETFs.

Risk Management

- Advanced traders might use dynamic hedging to manage the delta and gamma exposure of the options portfolio.

- Use protective options strategies like buying farther out-of-the-money options to cap potential losses.

Risk Parity Portfolio Management

Dynamic Rebalancing

- Monitor the risk contribution of each portfolio component.

- Rebalance the portfolio to maintain equal risk contributions from each asset or strategy, especially after significant market movements or volatility changes.

Leverage Management

- Use leverage judiciously to amplify the returns of lower-risk assets or strategies, including the VRP strategy, to achieve risk parity.

- Adjust leverage levels in response to changing markets and volatility to maintain the overall risk profile of the portfolio.

- Related: Options Strategies for Synthetic Leverage

Benefits and Considerations

Diversification and Risk Control

Using VRP in a risk parity framework enables the portfolio to benefit from diversified sources of returns and controlled risk exposure.

Market Neutrality

The VRP strategy, especially when delta-neutral, can provide returns that are less dependent on market direction.

For institutional traders, it’s also value-additive in that their product isn’t highly correlated with other asset classes or common strategies.

Liquidity and Exit Strategy

Make sure that the VRP strategy maintains sufficient liquidity to adjust or unwind positions easily in response to market changes or risk re-assessment.

Summary

This approach leverages the VRP’s potential to provide consistent income while using the risk parity model to balance portfolio risk.

This aims for more stable and diversified returns, as opposed to one-off trades (like covered calls on individual stocks).

Wheeling Strategy

The Wheeling strategy is an options trading technique that combines selling put options and covered calls to generate income in a cyclical manner.

It’s a popular strategy among traders looking for consistent income, as it harvests options premiums with manageable risk.

How the Wheeling Strategy Works

The Wheeling strategy begins with selling a put option on a stock you’re comfortable owning.

When you sell a put, you receive a premium as payment for agreeing to buy 100 shares of the stock at the strike price if the option is exercised.

If the stock price stays above the strike price by expiration, the put option expires worthless, allowing you to keep the premium.

In this case, you can simply repeat the process by selling another put, generating more income without purchasing the stock.

However, if the stock price falls below the strike price, you’re likely to be assigned the stock, meaning you’ll purchase 100 shares at that agreed price.

This is where the second part of the Wheeling strategy comes into play.

After being assigned the stock, you move to sell a covered call on the 100 shares you now own.

A covered call involves selling a call option with a strike price at or above the stock’s purchase price, receiving another premium in the process.

If the stock price remains below this call strike by expiration, the call expires worthless, and you keep the premium while still holding the stock.

This allows you to sell additional covered calls in subsequent cycles, continuously generating income from the stock.

If the stock price rises above the call’s strike price, the option is exercised, and you sell the stock at the strike price, completing one full cycle of the Wheeling strategy.

At this point, you return to a cash position, ready to start the process again by selling another put.

Benefits and Risks

The Wheeling strategy provides consistent income through premiums and allows for potential capital gains if a stock appreciates before a call is exercised.

It nonetheless requires significant capital to cover 100 shares if assigned, and there’s risk if the stock price drops sharply, as you may hold a losing position.

Additionally, the strategy can limit upside potential since selling covered calls caps gains if the stock rallies significantly.

Accordingly, the upside is limited.

But overall, the Wheeling strategy is a structured, cyclic approach to options trading that appeals to traders looking for recurring income and the possibility of owning quality stocks at reduced cost.

Conclusion

In this article, we covered a few of the main options strategies for income generation.

The covered call (for long positions) and covered put (for short positions) are very common.

The iron condor is another option for those who expect price to stay within a given range and express the idea in a relatively risk limited way.

A modified condor takes the covered call (or cover put) concept and converts it into the same shape as an iron condor by buying a put option to limit risk and shorting an additional call option.

The “wall” option strategy involves taking additional advantage of the volatility risk premium. It may involve the need for the trader to dynamically hedge the position given the overweighting of a short option position.

However, if the trader finds himself in this position, it’s designed such that a quality amount of money has already been made on the trade. Dynamic hedging can mean going long the underlying while also buying OTM puts to help protect profits.

The put option and option premium received from the calls also helps limit the risk involved in the trade. If it goes against the trader, typically only a small amount of money is lost. On the other hand, much can be gained if the trade goes favorably, though the trader will need to get the dynamic hedging part right.

The strategy can be applied to both bullish and bearish positions.

Selling put options on a security one would like to own at a certain price is also one of the most well-known options strategies for income generation.

If you believe something is too expensive, you can essentially get paid to wait.

However, between the time you put on the short put and the time it matures the fundamentals of the underlying security may not be the same and change your opinion as to what price (if any) you’d be willing to own the security.

Also, options being convex instruments gain in value in a non-linear way when price goes increasingly in the money, holding all else equal. This has implications for your account balance. Moreover, your margin requirements may increase at the same time, squeezing you from both sides (account equity plus higher collateral that needs to be held against the option).

Options strategies for income require a good understanding of market dynamics, risk management, and the specific mechanics of options trading. By carefully selecting and managing these strategies in light of their goals, traders can generate regular income while managing potential risks.

Minimize risk, maximize expected value

Above all, as a trader, you inherently want to minimize your risk. Betting on what’s most likely isn’t always prudent. Most trading mistakes are fundamentally about mismanaging risk.

You want to maximize your expected value while keeping prospective risk to a level that you can easily cover.

There will always be some risk that needs to be taken. It’s part of trading. But the goal is to get as much return per each unit of risk taken on.

And any trading strategy should be tried out in a limited- to no-risk way before deploying it at any scale.

Further reading: Long-Short Strategy: Improving Risk-Reward with Options Trading