QE and the Impact on Yields

There’s a lot of confusion regarding quantitative easing, also known as QE, and the impact on bond yields (longer-term interest rates).

Quantitative easing is the secondary form of monetary policy after interest rate-driven policy.

Once interest rate policy has been exhausted – when short-term interest rates are at about zero – then the focus shifts to QE to push down longer-term yields.

Quantitative easing and its process

QE is part of all major developed economies. The central banks of the US (Federal Reserve), Europe (ECB, BOE, SNB), and Japan (BOJ) all employ it.

Collectively, these economies are about 80 percent of the global financial markets. So QE is just part and parcel of trading these markets.

The QE process is fairly straightforward. The central bank creates money to buy bonds and, in some cases, other assets. This increases demand for those securities and pushes down yields.

In some respects, QE can help economies de-risk by placing the debts of over-leveraged entities onto the central bank’s balance sheet.

For example, QE decreases the supply of longer-term bonds in the market by removing them from private investors’ portfolios. This, in turn, pushes traders and investors into other types of assets.

QE can involve buying certain types of securitized assets in the US (mortgage-backed securities) and not just sovereign bonds.

QE can have a number of effects on bond markets. It works directly to lower long-term interest rates but can also have an indirect downward effect on shorter-term rates if QE is “unsterilized” – which means not offset with an equivalent amount of reverse repo operations that would remove reserves from banks’ balance sheets.

In addition, QE is typically successful in moving up stock prices because QE makes capital more available to the financial markets, which helps out these other assets.

QE also decreases the value of currencies, as central banks are devaluing their own money (i.e., money that they create).

It can also be devalued to an easier extent by buying foreign assets, like the Swiss National Bank has done by buying foreign stocks.

QE can also reduce domestic bond yields through expectations of currency devaluation.

The full-scope impact QE has on bond yields is an issue that still isn’t known with complete clarity. It’s hard to figure out exactly what QE does to bond yields entirely because it requires knowing the reflexivity effects.

In other words:

- how much quantitative easing was actually done and why

- in which markets was it done (e.g., government bonds, securitized assets, corporate credit, ETFs, equities)

- how does that feed through the financial system into the real economy, and

- how do changes in real economic variables (e.g., growth and inflation) feed back into financial markets

There are some theories about QE and its impact on bond yields:

The liquidity effect

The liquidity effect asserts QE increases liquidity (money in the financial system) and therefore lowers interest rates.

QE can do this in two ways:

- QE’s effect on increasing money supply and

- QE’s effect on central bank bond buying programs

QE also decreases the risk of holding bonds. And lower perceived risks means lower yields (investors demand less return).

QE has a greater impact when it is unexpected, which was the case in the first round of QE the Federal Reserve did after 2008 (beginning in March 2009).

This is because it hadn’t yet been discounted into prices. So it had a big effect when it did.

The portfolio effect

The portfolio effect says that QE has an “asset allocation” effect because traders and investors rebalance their portfolios into other things like stocks and commodities if they perceive them as safer than fixed income securities (bonds).

Aren’t bonds safer than stocks and commodities?

Typically bonds are backed by central governments or senior in companies capital structures and thus safer.

However, when money is being severely devalued and/or inflation is rising, people typically want to get out of cash and bonds, fearing they’ll be paid back in money of lower value.

This leads them into allocating into various types of inflation-hedge assets like equities, commodities, real assets, and potentially other things that can be considered potential stores of value (e.g., cryptocurrency).

The signaling effect

The signaling effect asserts that QE provides information to the market about upcoming policy changes even if it does not involve buying bonds directly.

There’s a debate among traders, investors, and central bankers about how QE exactly works in this respect.

Does it work through:

- Mechanical buying and selling of bonds?

- Or through expectations of what’s to come?

In reality, it’s a little bit of both.

Buying and selling right now is what mechanistically impacts prices, but expectations of the future also cause present buying and selling in markets.

QE announcements can set a lower bound on yields and provide guidance on future policy changes that stimulate growth and inflation.

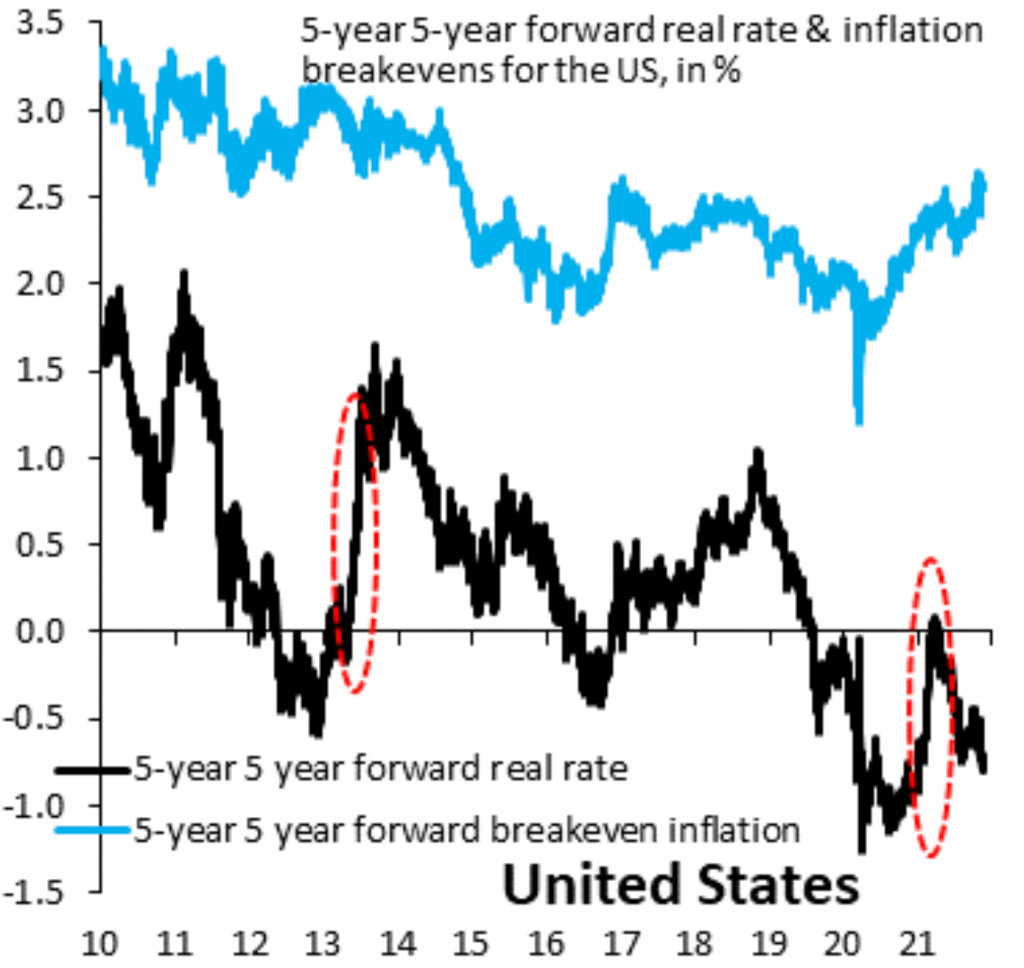

2013 (“taper tantrum”) and 2021 in the US Treasuries market is an example of Fed communications impacting buying and selling activity to position for the future.

QE works through expected inflation to ease borrowing conditions, but it does not work as well when longer-term interest rates are getting close to zero because QE is also out of room in its potential to lower yields further.

Nominal interest rates can’t go much below zero given a positive inflation rate is always going to be targeted and borrowers need real returns on their lending.

QE and bond yields: The QE debate

There’s still a lot of research needed to determine exactly how QE impacts bond markets – academics and private investors are still in the early stages of fully understanding QE’s entire effect on the economy.

What we do know is that traders and investors will expect higher returns from government bonds if QE increases liquidity and decreases perceived risks (i.e., makes it more likely that the QE will be temporary).

That being said, QE can have effects on bond yields that are unrelated to portfolio rebalancing. One QE effect that’s not understood is QE’s impact on financial stability.

QE may also help decrease government bond yields if easing helps banks become more stable by increasing capital ratios and decreasing bad assets through balance sheet expansion.

QE may even have a “spillover” effect of improving market confidence in banks’ ability to recapitalize themselves without fiscal support.

QE’s impact on bond yields may also heavily be a product of QE’s effect on inflation expectations.

Ultimately, QE has an indirect yet powerful impact on bond yields via QE’s impact on economic growth.

QE can increase real growth through higher aggregate demand and credit creation, which puts downward pressure on inflation on the supply-side and upward pressure on the demand side, and increases output and employment – both of these factors decrease the risk of holding bonds.

QE on liquidity and risks

As we’ve seen, QE increases liquidity and decreases perceived risks – so QE lessens investors’ reliance on fixed income securities as a safe asset (bonds) and more to assets like stocks and commodities because they are now seen as things that will recover very quickly in price when QE is ramped higher.

Essentially, this bypasses the need to own safe assets to some extent.

The full-scope impact QE has on bond yields is an issue that still isn’t well understood. Studying what exactly QE does to bond yields is hard when QE is not conducted at the same time and at different paces across all major central banks.

What we do know is that QE has had a significant impact on global policy changes since 2008 – QE was implemented in response to the emerging market (EM) debt issues of early 2010.

A QE taper means being prepared for another economic storm, so QE tapers have the potential to have an even bigger effect on bond markets than QE themselves.

If QE is successful at stimulating growth they will lead to higher inflation, which means traders need to adjust their portfolios toward higher yielding like stocks and inflation-hedge assets (commodities, real assets) rather than safe assets.

The effects of QE on market liquidity is another side-effect that impacts how traders expect bonds to behave.

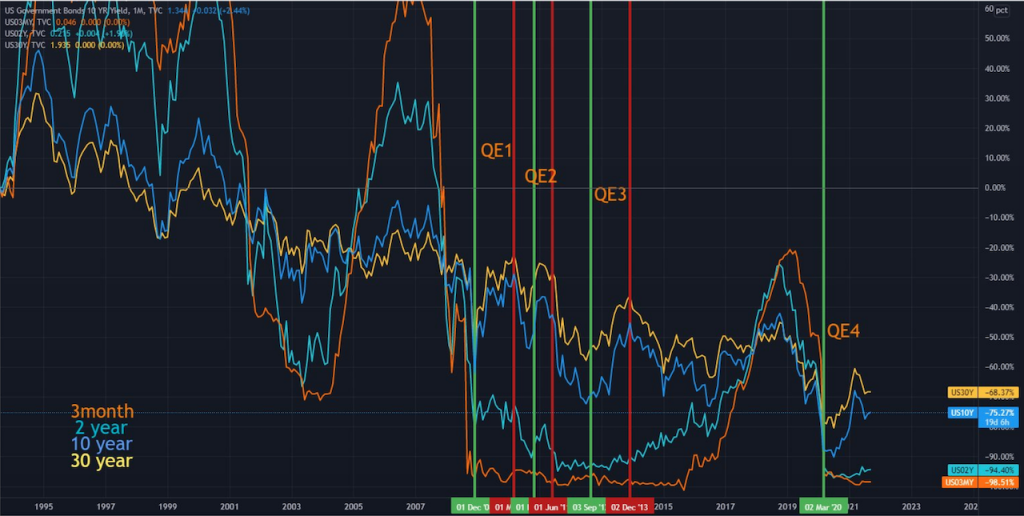

If QE decreases yields, then why did yields increase during previous bouts of QE?

Some look at charts of the beginning of QE start dates and seemingly observe the opposite from “QE pushes yields down”:

QE Periods vs. Interest Rates & Bond Yields

(Source: Trading View)

However, it lacks context.

What did nominal GDP do? What happened to real yields?

Whether yields are “high” or “low” depends on real economic variables. If QE helps increase nominal GDP and nominal yields rise in parallel, that’s healthy market functioning.

And QE is generally communicated into markets ahead of time, which impacts forward yields before official start dates.

Levels of yields are most important, not trend.

The riddle is essentially:

Why are yields 0-2 percent across the yield curve while inflation rates are well above that? (Because long-term bonds reflect long-term expectations of growth and inflation, can just focus on shorter tenors.)

In other words, why are investors perpetually accepting such negative real returns?

It’s because so much of the sovereign bond market is not private investors.

Yields are held so low – negative in real terms – because of government ownership of so much of the bond market to carry out their policy objectives.

That’s what all those trillions of dollars on central banks’ balance sheets are mechanically doing.

Under QE policy, there’s not enough private sector demand for the bonds so they buy the excess.

Mechanically, when the central banks buys bonds, prices goes up, yields go down.

QE in the context of today’s fiscal spending

If the Fed wasn’t buying bonds right now and allowed yields to rise to unacceptable levels all this fiscal spending would be like hitting the gas and brake at the same time.

They’re purposefully giving us the fattest spread between nominal GDP and nominal rates and the most negative real yields since the 1970s.

The combo of loose fiscal policy + ZIRP + QE is now giving us:

- High nominal GDP

- Low nominal yields

- Negative real yields

ZIRP + QE without aggressive fiscal policy gave us:

- Low nominal yields

- Low/negative real yields, but

- Sluggish nominal GDP

Nominal GDP was relatively slow in the 2008-2019 policy period because not a ton of that money was hitting the real economy.

The money doesn’t get into goods and services to a big extent unless paired with aggressive enough fiscal policy to direct the money to those areas.

When QE is working well, QE comes down to whether it adequately decreases government borrowing costs.

Previously QE was successful at this for the US, UK, and Japan. For eurozone QE regiments there have been more mixed results because it’s a quasi-pegged currency union.

In some countries, QE has failed to lower bond yields or long-term borrowing costs enough. The European periphery is one example (e.g., Spain, Portugal, Italty, Greece).

But that doesn’t mean QE has failed to stimulate growth in eurozone nations. Those nations just need looser fiscal policy backing up QE rather than less.

Why do interest rates matter?

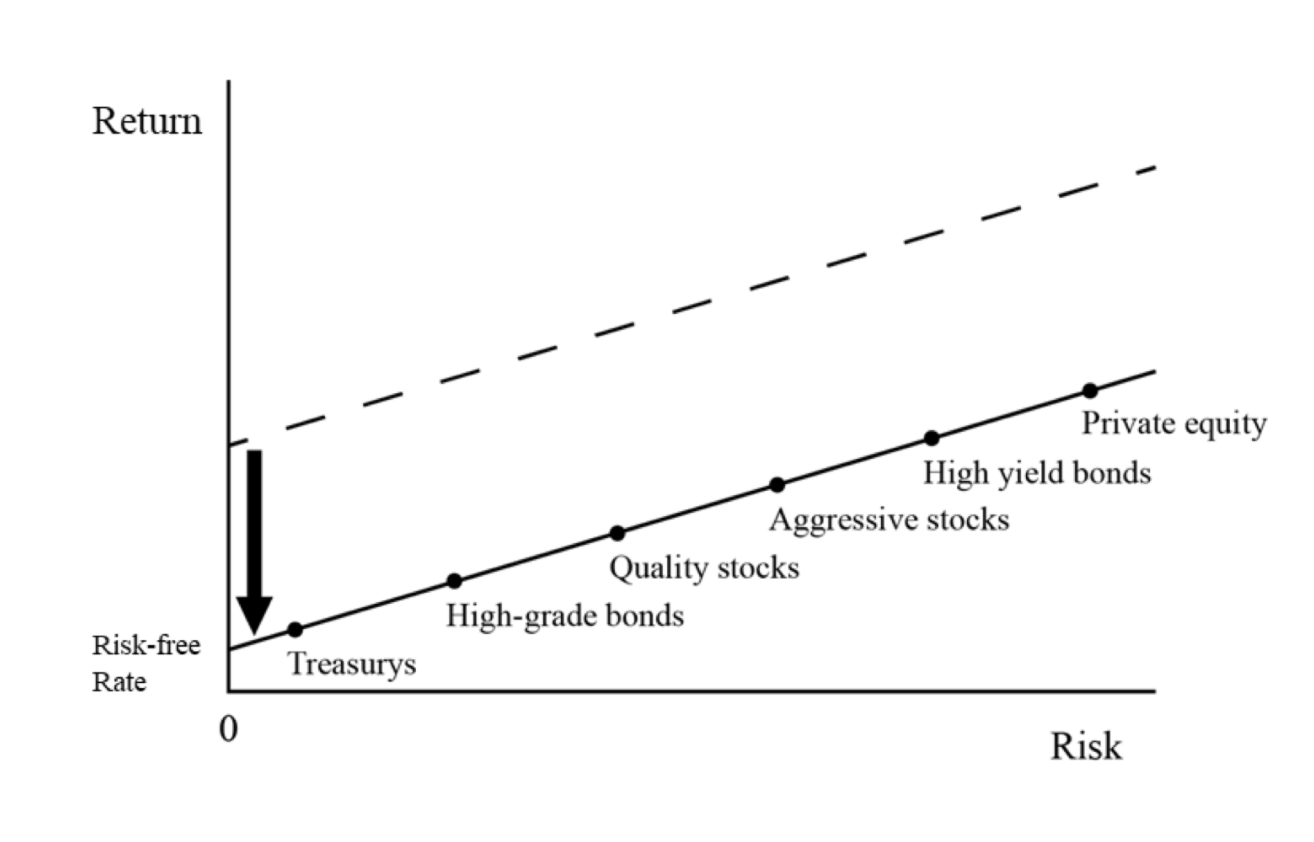

So much capital is chasing so few good investment opportunities because there’s an excess of money in the financial system due to QE (and other factors).

Everything comes down in yield.

If all kinds of safe assets give negative returns after adjusting for inflation, then people would switch their portfolios toward riskier assets like corporate bonds, stocks, private assets, and even cryptocurrencies.

QE vs. Yield Curve Control (YCC)

QE targets the quantity of bonds purchases.

Yield curve control (YCC) targets yield – i.e., quantity changes.

Under YCC, the central bank wants bonds yields to stay within a certain yield band. If it gets to the upper edge of that band, they buy in whatever quantity necessary. Also, if it gets to the lower end of that band, they could consider selling holdings to keep yields higher.

QE’s goal is getting money into the financial economy. Whether yields go up or down and whether that’s good or bad depends on context.

QE is generally used when fiscal policy isn’t doing enough, spreads are high (between short-term and long-term interest rates), and liquidity is tight.

YCC is generally used when the government has lots of borrowing needs and wants to keep yields in check. World War II was an example in the US.

As a more modern example, the BOJ did it in 2016 to control their 10-year bond yield.

QE vs. QT (Quantitative Tightening)

QT is also known as tapering or reverse QE.

QT is undertaken when a central bank deems that the economy is meeting its policy objectives or is “running hot” (inflation too high).

So they begin running off their bond and other asset holdings to slow things down.

QT can also work by not selling bonds back on the market and allowing maturing holdings to roll off naturally (with some small exceptions).

Conclusion

QE works on bonds because it reduces interest rates, which decreases bond yields and increases demand.

QE is specifically used to lower long-term interest rates and can act as a supplement to fiscal policy.

QE is seen as the next best thing to fiscal stimulus because QE stimulates aggregate demand. QE doesn’t help unemployment directly – because the Fed can only create money and change the incentives associated with credit creation – but it does put people back to work by lowering long-term yields, which can stimulate growth.

Ultimately, QE has an indirect yet powerful impact on bond yields via QE’s impact on economic growth.

QE’s impact on bond yields may also be a product of QE’s effect on inflation expectations.

If QEs are successful at stimulating growth they will lead to higher inflation, which means traders need to adjust their portfolios toward higher yielding like stocks and commodities and the appropriate amount of inflation-hedge assets rather than simply safe assets like bonds and cash.

Yield curves may be as important as GDP growth as a forward-looking indicator of economic health.

Pros

QE connects the balance sheets of private banks and central banks.

It helps liquidity and enables investments that were previously uneconomic because market dynamics had priced them out due to scarcity of supply or credit risk.

It lowers borrowing costs for governments and corporate borrowers.

At QE’s core is a belief that people will spend more if they have money available. QE takes the pressure off fiscal policy to do more because it can be a substitute or complement to fiscal policy – not just monetary policy alone.

QE can have effects that help GDP growth, inflation, and employment. QE is not just money printing but instead changes the composition of private portfolios toward riskier assets like equity and credit instruments for borrowers who need them most.

QE works best in coordination with fiscal policy, where both work together to get the economy closer to maximum output, increase inflation expectations, and reduce risk premiums on financial assets.

QT works best when central banks believe the economy isn’t overheating but managing liquidity properly so it doesn’t spillovers into inflation. QT can work well when QE has been exhausted (longer-term rates are close to short-term rates) and is no longer needed.

QE serves a function that helps prevent recessions from becoming deeper than they otherwise would be without the policy support. QE can also help with significantly reflating assets, though it’s not designed to do so explicitly.

Other benefits of QE include:

- it attracts foreign capital into domestic equity and bond markets

- reduces exchange rate volatility

- promotes easier monetary policies in other countries and

- produces signals that the central bank will remain committed to price stability without serious concern for financial and economic stability

Cons

QE can create asset bubbles, especially where the money supply and credit creation increases too quickly – e.g., housing price bubbles, stock market bubbles, and other types of frothy market price increases as a result of QE’s expansion.

QE may lead to misallocation of capital from productive investment toward things that are heavily speculative.

In other words, financial wealth can increase faster than real wealth, which brings with it its own problems.

Moreover, how that wealth is distributed tends to be highly unequal because the holdings of financial assets tend to be concentrated among smaller sets of the population. For example, it’s not uncommon for just 10 percent of the population to hold more than 90 percent of all financial wealth.

So despite the positive effects on the labor market and income, it can drive wealth inequality, which can feed into social and political disruptions and other internal conflicts.

QE is also used when central banks want to encourage borrowers who might not be in a position to borrow or would otherwise be creditworthy borrowers. The central bank lacks the macroprudential tools to cut down on risk in specific pockets that could produce systemic risk.

QE can also create currency depreciation. This isn’t bad on its own, but it can act as a discreet tax, increase inflation, and make imports more expensive.

QE can create moral hazard if borrowers over-borrow because they know the central bank will buy their debt via QE.

In other words, there isn’t a healthy fear of risk, so the skew becomes inappropriately asymmetric.

QE has market limits for how deep it can go before yields are overly compressed or sensitive areas start getting crowded out by excessive bond buying (e.g., Swiss government bonds within the Eurozone).

QT’s effectiveness depends on the state of the economy when tapering begins.