Does the US Dollar Strengthen During Fed Tightening Cycles?

First, let’s cover some basics about how central banks and their processing of raising and lowering interest rates impacts currencies.

What is a tightening cycle?

A tightening cycle involves the central bank of a country raising interest rates.

For example, if it was believed to be good for the economy, the Fed may raise its benchmark interest rate thus making saving money more appealing than borrowing money. The result of this action, holding all else equal, would be to strengthen the dollar.

What is a loosening cycle?

A loosening cycle involves the central bank of a country lowering interest rates.

This would encourage spending over saving by lowering savings accounts returns or reducing loan costs for consumers and businesses alike. As a result, the currency becomes less valuable as buyers seek higher yields in other currencies.

It also pushes market participants into riskier assets given the low returns on cash.

When do tightening or loosening cycles start?

Loosening cycles have historically begun when the economy is showing signs of weakness.

This may be shown by low interest rates, low inflation, low economic growth, high unemployment, among other indicators.

Interest rates are increased once the economy begins to show signs of recovery.

Loose monetary policy occurs when central banks begin cutting interest rates in order to spark economic activity – usually after growth has stalled or is falling and inflation has fallen below its target rate.

Central bankers always target an inflation rate of at least zero to avoid deflation and prefer that it be positive but low.

Are tightening cycles bullish for a currency? And why would this be true?

On average, during tightening periods the dollar tends to strengthen versus foreign currencies when markets begin discounting the fact that the central bank will begin raising rates faster than what was previously discounted.

This happens because international money flows into US investments as domestic interest rates rise, increasing demand for US assets.

In addition, the Fed’s large holdings of Treasuries tend to strengthen the dollar by raising long-term interest rates when it sells securities to soak up liquidity during or after a tightening cycle has started.

(However, because of the impact of tightening on inflation – will lower it, holding all else equal – this has the influence of lower long-term interest rates. So, the net impact on bond yields, is more nuanced based on the competing factors.)

Related: How Does QE Impact Yields?

Why do loosening cycles weaken a currency?

Generally, international money flows out of US investments and into foreign markets when policies are expected to result in faster growth or rising inflation rates due to expectations of higher interest rates in other countries relative to those in the US.

This reduces demand for US assets and puts downward pressure on the value of the dollar.

In addition, when the Fed is buying fewer securities from banks with all that liquidity, that reduces upward pressure on the dollar.

If a central bank is dovish (favors looser policy), how can that be bullish for the US dollar?

A weaker currency can actually make a central bank’s interest rate policy more effective.

For example, if the Fed were to lower rates further from zero (and more negative in real terms from their already very negative levels), this would have been futile as it doesn’t largely help promote more credit creation.

It also hurts banks’ profitability in various ways, where it has trouble lending at rates higher than the rates at which it borrows, part of a process known as disintermediation.

But the Fed can get easier policy through QE/asset buying or through policy coordination with fiscal policymakers to get money and credit to where it’s needed.

In this case, the Fed could use a weak currency to fight deflation and incentivize buying, borrowing, and investing.

If a central bank is hawkish (favors tighter policy), how can that be bearish for the US dollar?

Rising interest rates and expectations of more aggressive policy tightening will typically support a currency, but this doesn’t always happen.

When we talk about the value of a currency, it’s always in relative terms.

This may indicate that traders may be anticipating a decline in the relative growth and yield advantage versus other markets.

For example, if we’re talking about the US, this could mean falling relative to Europe, Japan, and emerging-market countries. A weaker dollar typically means higher inflation for longer, which could lead to higher interest rates.

How do central banks make policy with respect to what it means for their currency?

Central bankers consider many things when setting policy, including:

- economic growth in both their own economy and global economy

- employment levels

- inflation rate relative to their goals

- the exchange rates of their currency against other currencies

- demand for imports and exports among countries that are reliant on trade with each other, and so on.

If a central bank’s currency is weakening or strengthening beyond its control through market forces, it can opt to intervene by buying or selling its own domestic currency in markets where it has some degree of influence over price discovery.

The most important thing is how closely they’re achieving their mandate.

This is commonly low and stable inflation, or low and stable inflation plus maximizing output (with a third shadow mandate of financial stability, which includes things like avoiding bubbles).

If the central bank is overly passive and allows too much inflation, it can lose credibility.

If it’s too loose with its policy, which can include allowing its currency to weaken more than what’s necessary, this could cause problems with inflation or financial stability (i.e., bubbles).

Therefore, they must be able to find a trade-off in policy, between what they can control and what is influenced by market forces beyond their control.

Central banks controls money and credit creation – assuming it’s denominated in their own currency.

But they can’t control the supply side of an economy to much of an extent. They can’t control supply chains, structural worker shortages, and so on.

There are several ways that a central bank makes policy decisions about interest rates.

The various mechanisms of central bank policy

– Policy Rule: Fed observers commonly use an estimated model of how the economy works called the Taylor Rule.

It does not just follow this rule but has discretion for setting appropriate values of certain variables in the model depending on how things actually transpire.

It shows how appropriate monetary policy might be relative to where it “should be.”

– Interest Rate on Reserve Balances: If aggregate demand is high, then the interest rate that banks pay to borrow reserves would be increased.

This reduces the amount of borrowing and lending activity by banks (or it increases the cost of doing so). If aggregate demand falls too low, this will reduce inflationary pressures because there’s less money chasing fewer goods.

It also decreases loan margins for banks because they can’t charge as much interest to borrowers who must compete with each other for funds at lower rates since supply has expanded (and credit standards are generally looser than usual).

This generally means interest rates on reserve balances at central banks are used as a policy tool during recessions or liquidity traps where money growth is needed but borrowing and lending activity is depressed.

– Open Market Operations: Central banks buy or sell bonds in open markets, which increases or decreases the supply of reserves out there for banks to borrow.

This can be used as a policy tool during normal times when interest rates are near zero.

But it’s generally less effective relative to other methods because bond purchases are at the discretion of private investors and banks who are willing to sell their securities.

Moreover, QE and other forms of open market operations largely work through the financial economy and work into the real economy in a very indirect way.

– Standing Facilities: These are funds available to central bank counterparties at their own discretion.

These include things like:

- Primary Credit (discount window lending at primary dealers)

- Term Primary Credit (lending against government securities through auctions)

- Extended Collateral Term Repo Facility (ECTRF, overnight lending that’s collateralized by non-marketable assets)

- Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF, liquidity absorption and facilities set up with different qualities for lending)

- Standing Liquidity Facility (SLF, lending to non-depository institutions against certain types of collateral)

- Secondary Credits (extending credit in the event of a “liquidity problem)

- and various other setups

If ordinary open market operations are insufficient in liquidity absorption, central banks can make these facilities available. This means that they provide loans in special circumstances when not all lenders are willing to lend or private borrowers seek funds.

– Discount Rate: Banks who buy short term debt from primary dealers can get it at a discount rate which is an interest rate reduction for placing funds with the central bank.

It’s often used by policymakers to prevent reserves from being too scarce during times where interest rates are near zero because money and credit growth has weakened.

The central bank wants to keep excess liquidity very low because it creates inflationary pressure.

In normal times, it does this by either not lending at all or setting a discount rate that’s high enough to discourage borrowing from the central bank (unless private bond purchases are weak).

– Reverse Repos: Sometimes called repos but actually reverse repurchase agreements in which the central bank agrees to buy securities back in the future for an interest fee.

These can be used in different periods of time when there might otherwise be excessive liquidity around and the central bank doesn’t want markets flooded with reserves.

– Foreign Exchange Operations: If demand for domestic currency is too weak compared with what other countries are using, then active foreign exchange intervention could help strengthen its value relative to other, and vice versa.

This is often called direct FX intervention. It works by selling or buying foreign currency through open market operations.

If the central bank is only trying to weaken its own currency, this means it must buy up enough of what others are selling until it becomes scarce relative to everything else out there which makes the value go up.

Sometimes countries don’t want to see their currencies strengthened because exports become more expensive for foreigners who use other currencies, while imports become cheaper for residents in that same country.

– Official Sector Transactions: Central banks can participate directly in transactions with other central banks if they’re seeking additional liquidity absorption too aggressively outside of their own domestic markets.

They might also do so when private bond purchases are weak during times of financial stress. These transactions are often conducted without fanfare and aren’t always

– Exchange Rate Targeting: Exchange rate targeting is done as either part of a currency union or to tie one’s currency to that of a global reserve currency, which is known as currency pegging.

In instances of pegging, this is commonly either tied to either:

- the world’s top reserve currency (i.e., the US dollar), or

- the currency of their primary trade partner

Countries will often want to correct imbalances in trade by intervening in currency markets and devaluing their own currencies (which makes imports more expensive and exports cheaper and therefore tends to increase exports and decrease imports).

Tightening cycles in the historical context

When unemployment drops and inflation rises, you can expect the Federal Reserve and other central banks to be aggressive in raising interest rates and withdrawing liquidity in other ways (e.g., running down their balance sheets).

Most notably this has implications for stocks. Less liquidity often means a pullback in stocks, especially if the tightening is done faster than what’s discounted into interest rates and bond futures markets.

But it also has implications for currencies.

When the interest rate on one currency rises relative to another, that makes that currency more attractive, holding all else equal, because it yields more.

In currency valuation terms, it’s often referred to as the relative rate differential.

The 2022-23 period is one such example of where the Fed is more aggressive than the ECB.

The Fed will hike interest rates and let its balance sheet run off, while the ECB will end its PEPP programme and phase it out over the course of about a year before hiking interest rates after that.

That kind of disparate policy response widens the rate differential in favor of the US dollar.

In theory, that should benefit the USD against the EUR.

But in practice, things are more complicated because markets are forward looking. In other words, it’s not so much what happens but what happens relative to what’s already discounted in the price.

Does the dollar always strengthen when the Fed tightens its monetary policy?

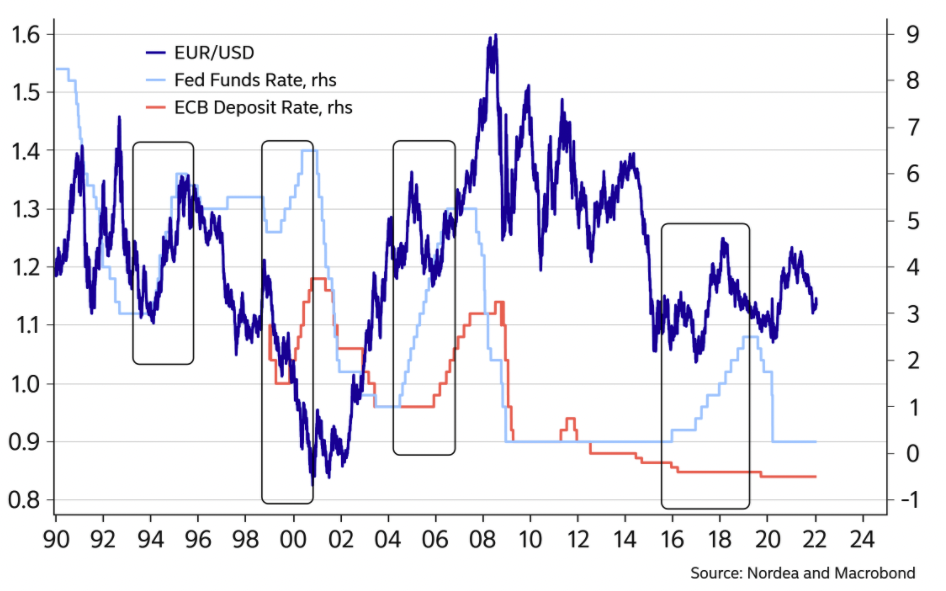

A look at the tightening cycles over the past 30 years indicates that things are more complicated than they seem.

In reality, it actually appears that the EUR/USD has appreciated more than moved down during tightening cycles.

Tightening cycles are also not that frequent. Over the past 30 years, there have been four tightening cycles.

This closely coincides with the fact that business cycles tend to be 5-10 years long.

And all of these tightening cycles have taken place under quite different circumstances.

Past cycles are a guide for the future, and there is some learning to be derived from all of them, but circumstances were often different in those cycles relative to the current situation.

Below we can take a closer look at the EUR/USD and the last four Fed tightening cycles.

The four previous cycles are different with respect to the duration and magnitude of the interest rate hikes.

The four tightening cycles have gone on for between 11 and 36 months. Moreover, the range of the tightening – in terms of the fed funds rate – has been 175 to 425bps.

Fed tightening cycles 1990-2022

It’s worth noting that of the four previous tightening cycles, each cyclical peak and each cyclical trough has been more shallow than the one before it.

This is because of greater indebtedness relative to output.

When a country becomes more indebted relative to what it produces, then the economy is less able to support high interest rates.

It’s much easier for debt servicing to swamp the cash flows being produced in the economy, which causes a downturn in financial assets first, followed by a drop in the real economy to get income and expenses and assets and liabilities back in line.

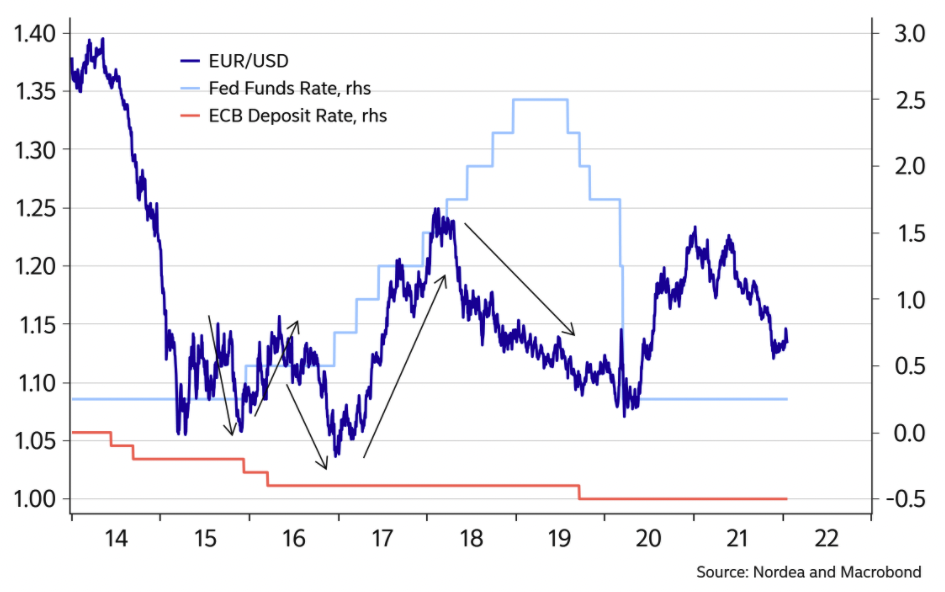

#1 Dec 2015 to Dec 2018 – tightening of 300bps

The tightening cycle back in 2015 to 2018 was the longest of the four, but it wasn’t the most aggressive.

The EUR/USD fell from 1.15 to 1.06 before the first 25-bp rate hike in December 2015. The exchange rate moved back up to 1.15.

But before the second rate hike, the EUR/USD exchange rate went below 1.05.

Below 1.05 means the dollar was strong (and the euro was weak). But when then-ECB President Mario Draghi made an optimistic speech in March 2017, it caused a huge repricing of the euro and the EUR/USD surged from below 1.05 to 1.25.

This, in turn, left no positive impact on the USD from the Fed’s five rate hikes.

Nonetheless, toward the latter part of that Fed tightening cycle in 2018, the EUR/USD dropped back below 1.15.

So taking the cycle altogether, there was no strong and positive correlation between the US dollar and Fed rate hikes.

Rate differentials are a key part of currency movements, but it was a period where various key factors mattered for the EUR/USD exchange rate.

Chart 2 Fed tightening cycle 2015-2018

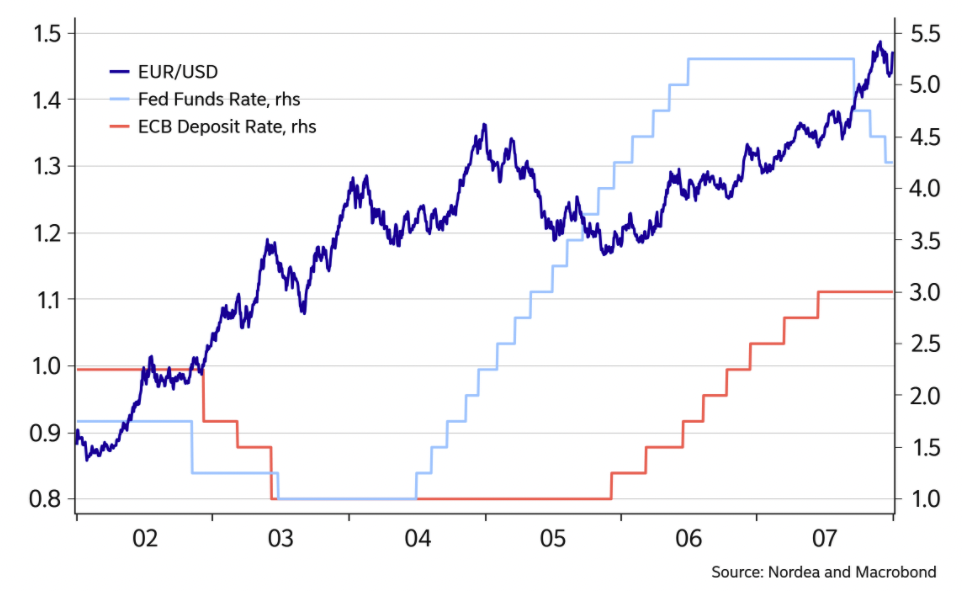

#2 June 2004 to June 2006 – tightening of 425bps

The 2004 to 2006 cycle was the most aggressive in terms of how much the Fed Funds rate was hiked.

But this tightening cycle occurred when the US trade deficit was the main driver of the US dollar.

A wider balance of payments deficit is a net negative for a currency, holding all else equal. It means the relative capital flow is going from the deficit/debtor country to those who serve as creditors.

The trade deficit was the single most important factor that took the EUR/USD from below 0.90 in 2002 and all the way back up to more than 1.50 before the financial crisis in 2008.

Rate differentials mattered, but during this period the primary focus of traders was the monthly trade numbers and TIC data from the US.

Accordingly, the positive impact on the US dollar when the Fed went on a two-year tightening cycle was imperceptible.

This hammers home a key point that positive factors can be offset by factors that negate it.

If the interest rate doesn’t compensate enough for the underlying capital flow, then a currency can fall.

This is a key factor in emerging market tightening cycles. When the interest rate offered on the currency isn’t enough to offset the inflation rate plus the influence of the underlying capital flow, then the currency is likely to weaken.

A classic ‘currency defense’ involves offering a high enough interest rate to both offset the inflation rate and account for the balance of payments situation.

This helps create a two-way market, rather than a one-sided market.

Oftentimes, policymakers will allow a currency to fall all at once, which can help close the balance of payments deficit (makes exports cheaper and makes imports more expensive).

Chart 3 Fed tightening cycle 2004-2006

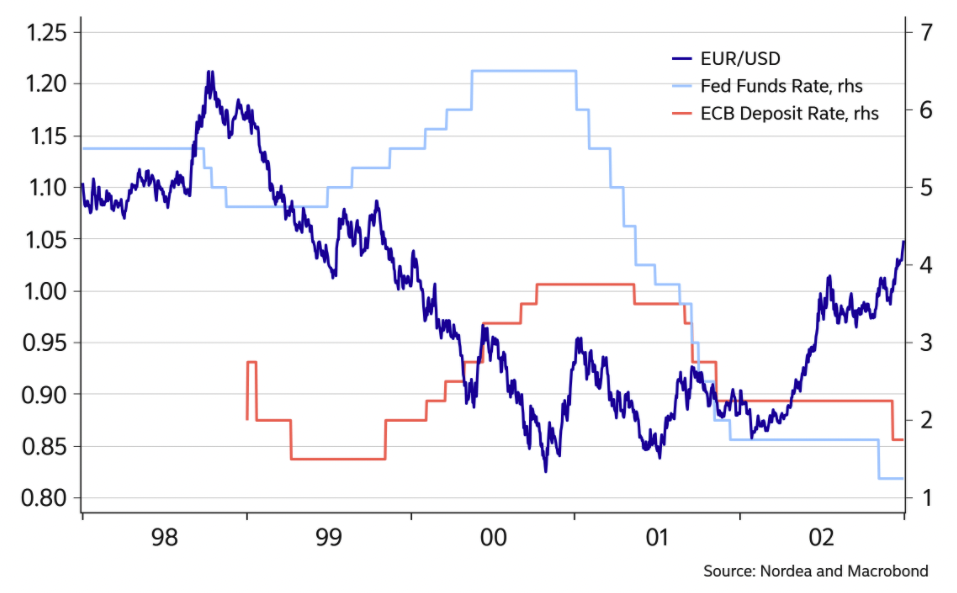

#3 June 1999 to May 2000 – tightening of 175bps

The Fed tightening cycle back in 1999-2000 was the shortest and the least aggressive one.

It was essentially a continuation of the 1994-1995 one. The 1997-1998 period saw modest rate cuts to help offset the impacts from a bevy of impacts – 1997 Asian currency crisis, 1998 Russian default, and the 1998 potential systemic threat of the LTCM blowup.

The EUR/USD fell a lot during this cycle, which might cause one to come to the conclusion that the Fed tightening cycle had a positive impact on the USD.

However, there were other variables at work.

In 1999-2000 there was one dominant force pushing the EUR/USD lower. From the beginning of 1999 (which saw the official launch of the euro) and until late 2000, the EUR/USD dropped from 1.20 to below 0.90.

At the time, the euro was in such a nascent stage, there was skepticism if it would be a success.

Tying lots of different economies together through a common currency despite having very different economic conditions among them makes the euro a risky long-term proposition.

Even today, the economically weaker periphery countries see a currency that’s too strong for their own domestic conditions whereas traditionally stronger economies like Germany see a currency that’s too weak for their own.

This tends to lead to surpluses in stronger economies and deficits in weaker ones, and can lead to a lack of unity and friction between countries.

Currency regimes that are out of whack relative to the fundamentals eventually split up. It’s all a matter of how it’s managed.

There are pros and cons to countries being on the euro.

For many, they get to enjoy the benefits of a stable currency and being part of a top global reserve currency system. But at the same time, they must forfeit control over changing policy in light of their own conditions.

Concerted intervention would help to stabilize the euro in the late autumn of 2000. The Fed participated, as well, albeit reluctantly despite the general global benefit.

Chart 4 Fed tightening cycle 1999-2000

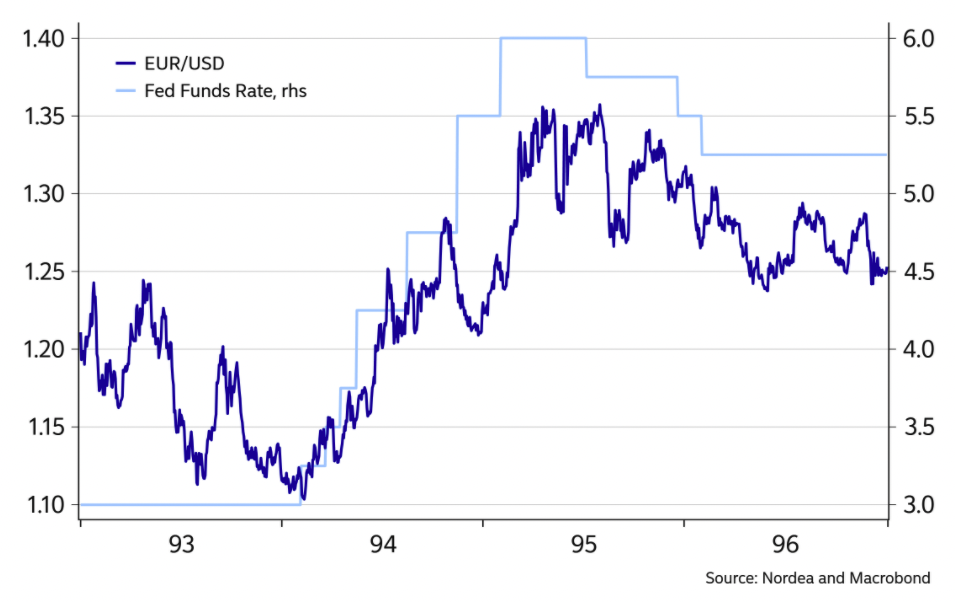

#4 Feb 1994 to Feb 1995 – tightening of 300bps

The tightening cycle in 1994-95 is a bit different when trying to understand the impact on the US dollar from Fed’s rate hikes.

Back then the FX regimes were different. The European Monetary System had a crisis in 1993 and several European currencies were going to be phased out later in the decade with the euro being put into place.

The Deutsche mark was the top European currency at the time and it outperformed the USD during the cycle in 1994-95.

Chart 5 Fed tightening cycle 1994-1995

Conclusion: Every cycle is different

As the Fed’s tightening cycle relates to the US dollar, we can see that every cycle is different.

There are always lessons to be learned from financial history, but it’s critical to know the cause-effect drivers rather than blindly following the past.

It’s always a matter of what the key drivers are at any given time.

The 2022-23 period is another period where interest rate differentials are a key part of the EUR/USD exchange rate.

But other factors enter into the equation. For example, if traders and investors drop US stocks that could reduce the USD in favor of other currencies.

And it’s not how things transpire, it’s how they transpire relative to what’s already discounted into markets. If there are rate hikes from the Fed that come faster than what’s discounted in, that could boost the USD.

But if it comes later than discounted, then the initial market response could be negative for the US dollar. There are also other factors, such as the move into safe haven currencies when markets worry about risk.

‘Safe haven’ currencies often mean those that are used to borrow in to buy risk assets. (JPY and CHF are commonly used.) When risk assets are sold off and there’s a deleveraging, it’s often a benefit to those particular currencies.