Volatility Carry Strategy

Most traders and investors chase returns through price appreciation, but one of the most persistent and overlooked sources of profit lies in the “carry” earned simply by holding certain exposures, especially in when it comes to volatility (often considered its own asset class).

The volatility carry strategy works to systematically harvest the premium embedded in implied volatility relative to what actually materializes.

The strategy is essentially about the market’s chronic overpricing of risk.

We look at the strategy’s foundations, mechanics, risks, and performance, to help traders understand and potentially use one of the most misunderstood return streams in modern finance.

Key Takeaways – Volatility Carry Strategy

- Volatility carry profits from the market’s consistent overpricing of future risk, captured through the implied-realized volatility spread.

- The Volatility Risk Premium (VRP) is a structural pricing bias, much like insurance, where implied volatility exceeds what actually occurs.

- Traders harvest volatility carry via options, VIX futures, and institutional trading products like variance swaps.

- Each offers different exposures to curve shape and risk.

- The return profile is highly asymmetric, with smooth gains punctuated by sudden, severe drawdowns during volatility spikes.

- Crowded trades and leverage can create systemic feedback loops.

- Example: The 2018 “Volmageddon” collapse of short-volatility ETPs.

- Volatility carry is best used alongside long volatility strategies or in diversified carry portfolios to balance return generation with protection in market stress.

Understanding Carry Across Asset Classes: Foundations and Framework

The concept of “carry” is one of the most fundamental yet misunderstood ideas in markets.

At its core, carry refers to the expected return from holding an asset assuming its market price doesn’t change.

This return arises not from capital appreciation, but from structural features (such as interest, yield, or roll dynamics) that are baked into how different assets behave over time.

What Is Carry?

Carry is the net income from owning an asset.

It could be interest earned, dividends received, or profits from rolling futures contracts.

Crucially, it’s calculated assuming the price of the underlying asset remains unchanged.

Positive carry means you’re being paid to hold the position; negative carry means you’re effectively paying to hold it.

Carry in Fixed Income: Riding the Yield Curve

In bond markets, carry is often the difference between a bond’s yield-to-maturity and the short-term interest rate used to finance it.

If the yield curve is upward-sloping, as it typically is, longer-dated bonds provide positive carry.

Investors also benefit from “roll-down,” where a bond’s value increases as it moves closer to maturity along a steep curve.

Currency Carry: Interest Rate Differentials

In FX markets, carry is driven by borrowing in low-yielding currencies and investing in high-yielding ones.

This strategy, which we covered in more detail here, works well when exchange rates are stable but is highly sensitive to currency moves.

A strong funding currency can erase all gains.

Likewise, a weak higher-yield currency can wipe out all the interest.

Equity Carry: Dividends vs. Financing Costs

For equities, carry equals dividend yield minus financing costs.

If dividends exceed borrowing costs, the position has positive carry.

This was rare in the 2000s but can reappear during periods of low interest rates and high dividend yields.

Commodity Carry: Roll Yield and Storage Economics

Commodities express carry through the futures curve.

Markets in backwardation (future prices below spot) offer positive roll yield, while contango (future prices above spot) creates negative carry due to storage and financing costs.

Related: Contango & Backwardation Convergence Strategies

Summary Table

| Asset Class | Source of Carry | Primary Instruments | Key Risks |

| Foreign Exchange | Interest Rate Differential | Forwards, Futures, Swaps | Exchange Rate Risk, Interest Rate Changes |

| Fixed Income | Yield to Maturity vs. Financing Cost (Yield Curve Slope & Roll-Down) | Bonds, Futures | Yield Curve Shifts, Credit Risk |

| Equities | Dividend Yield vs. Financing Cost | Stocks, ETFs, Futures | Price Declines, Dividend Cuts |

| Commodities | Roll Yield (Convenience Yield & Storage Costs) | Futures | Spot Price Changes, Term Structure Shifts |

| Volatility | Implied vs. Realized Volatility Spread (VRP), Term Structure Shape | Options, Futures, Swaps, FVAs | Volatility Spikes, Tail Risk, Gamma Risk |

What Is Volatility Carry? Definitions, Term Structure, and the Implied–Realized Spread

Volatility carry is a specialized extension of the broader carry concept, applied to volatility itself as an asset class.

While traditional carry strategies collect income from interest, dividends, or roll yield, volatility carry captures returns from the consistent overpricing of future volatility.

It reflects a structural imbalance between what markets expect volatility to be and what it actually turns out to be.

Defining Volatility Carry in Simple Terms

At its simplest, volatility carry is the profit earned by selling implied volatility when it tends to overestimate the volatility that ultimately occurs.

This is typically done by selling options (which embed implied volatility) or shorting volatility derivatives like VIX futures.

The seller earns a premium based on the market’s expectation of future uncertainty and keeps that premium if realized volatility stays low.

This spread, between what the market implies and what happens, is known as the Volatility Risk Premium (VRP). It’s the heartbeat of volatility carry.

The Implied vs. Realized Volatility Spread

Implied volatility (IV) comes from option prices.

It represents the market’s consensus estimate of how volatile the underlying asset will be over the life of the option.

Realized volatility (RV), by contrast, is backward-looking. It’s calculated from actual price movements over a given period.

Across most markets and timeframes, implied volatility is persistently higher than realized volatility.

This bias creates a systematic opportunity: by selling options (shorting implied vol), one can consistently profit if realized vol comes in lower.

This consistent overpricing is form of insurance pricing driven by fear.

Riding the Volatility Curve: Term Structure and Roll Yield

Volatility also has a term structure, just like interest rates or futures prices.

For VIX futures, the curve is usually in contango, meaning futures prices are higher the further out they are.

This reflects investors’ fear of future spikes in volatility and their willingness to pay a premium for protection.

When a trader shorts VIX futures in a contango environment, they earn a type of “roll yield” as those futures decline in price toward the spot VIX at expiration.

This roll down the curve, just like riding the yield curve in bonds, is another dimension of volatility carry.

Together, the implied-realized spread and the term structure shape define the two dominant ways traders harvest volatility carry: through short option positions or short VIX futures.

Example Strategy

Here’s a conceptual example.

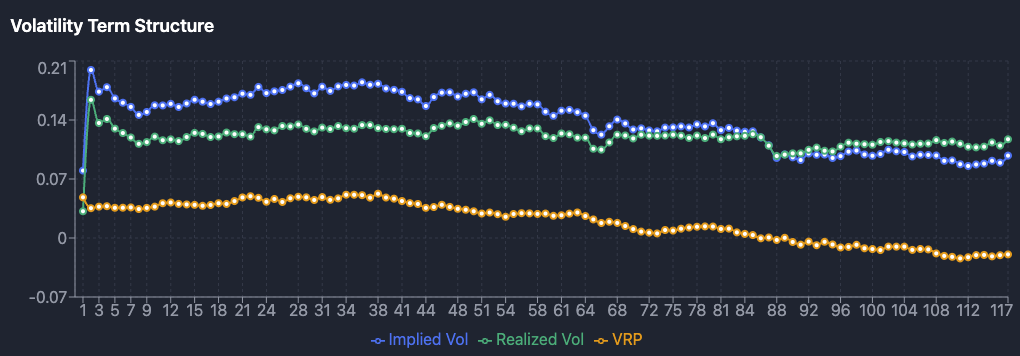

1) Volatility Term Structure Chart

This is the most critical chart for understanding the volatility carry engine.

It shows Implied Volatility (IV) is generally (but, importantly, not always) above Realized Volatility (RV).

The gap between the two is the Volatility Risk Premium, i.e., VRP.

Over time, the VRP gradually declines, which explains why the P&L plateaus and eventually dips.

A falling VRP means less premium is available to harvest, and the strategy becomes less profitable (or riskier) as a result.

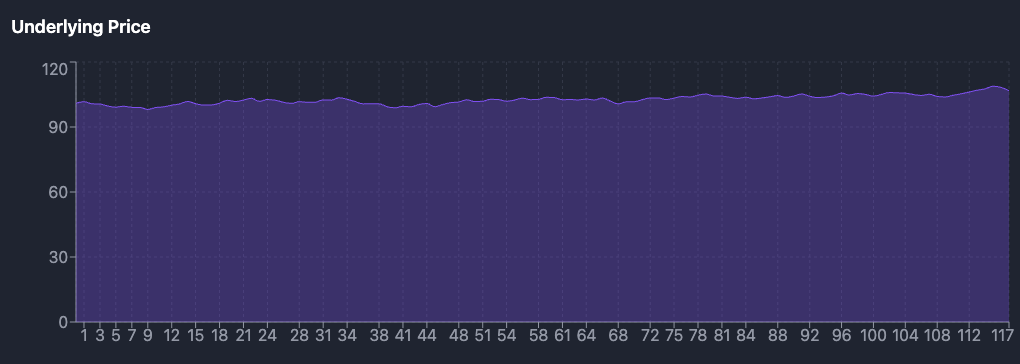

2) Underlying Price Chart

The underlying asset’s price remains relatively stable throughout the period, hovering within a narrow band around the 95–105 range.

This low realized volatility supports the profitability of the carry strategy, as sold options or short volatility positions are unlikely to be stressed by large price moves.

The flatness here reinforces the idea that the strategy is profiting not from directional movement, but from volatility being overestimated.

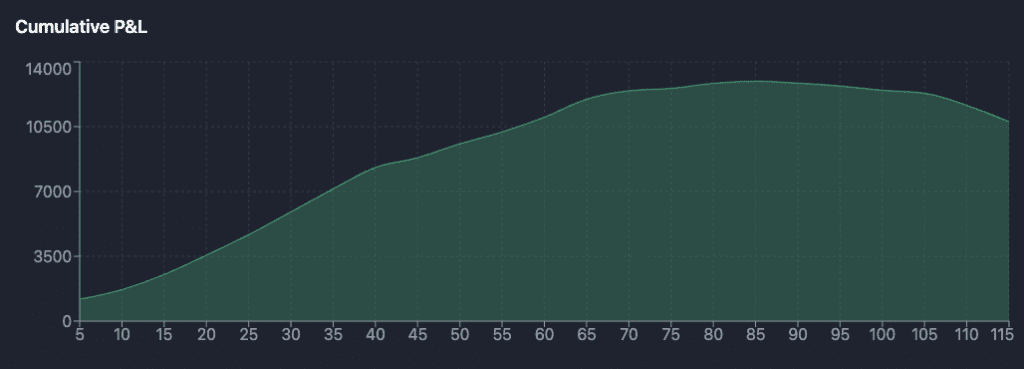

3) Cumulative P&L Chart

This chart shows the cumulative profit and loss of the volatility carry strategy over time.

It rises steadily from left to right, reflecting consistent returns during a prolonged period when the strategy is profitable.

Nonetheless, as time went on, there’s a visible decline in profitability, followed by a plateau and then even losing money.

This pattern is typical of volatility carry: small, steady gains punctuated by losses when volatility spikes unexpectedly.

A trader might also look at this graph to better understand whether the trade has gotten more crowded and whether it needs to be adjusted.

Modeling the VRP: Mathematical Frameworks and Variance-Based Instruments

While volatility carry can be described in intuitive terms, selling insurance and pocketing the premium, its deeper understanding requires formal modeling.

As mentioned, the VRP is the quantitative expression of the difference between implied and realized volatility, and it can be analyzed within several financial frameworks.

These models clarify the conditions under which the VRP exists, how it’s harvested, and what risks it entails.

Black-Scholes and the Hedged Option Seller

In the Black-Scholes model, implied volatility is assumed constant and known.

A trader who sells an option and delta-hedges the position theoretically breaks even if realized volatility matches the implied input.

However, if implied volatility (σᵢₘₚ) exceeds realized volatility (σᵣₑₐₗ), the trader profits.

The formula for the profit-and-loss (P&L) of a continuously hedged short option is:

PnL ≈ (1/2) ∫ Γₜ Sₜ² (σᵢₘₚ² – σᵣₑₐₗ²) dt

Where Γ is the option’s gamma and S is the price of the underlying.

Since gamma is positive for long options, the seller (short gamma) benefits when implied volatility is higher than what materializes.

This is the basic mechanical expression of VRP.

Stochastic Volatility and the Heston Model

In reality, volatility fluctuates.

The Heston model – talked more about here – addresses this by introducing stochastic volatility, where the variance follows its own mean-reverting process.

While delta-hedging in a Black-Scholes world may be sufficient, stochastic volatility requires accounting for vega risk, the sensitivity of option value to changes in implied volatility.

Here, the VRP is embedded in both the shape of the volatility surface and the hedging error arising from volatility uncertainty.

A trader harvesting VRP in this model accepts imperfect hedges and pricing mismatch in return for premium income.

Jump-Diffusion and the Merton Model

The Merton model adds another layer: sudden price jumps.

These are events that cannot be hedged using delta alone.

In this framework, the VRP must be large enough to compensate the trader not just for diffusion risk but for catastrophic, unhedgeable jumps.

The need for this additional premium explains why VRP is so persistent and elevated (because it compensates for truly nonlinear risks).

Pure Instruments: Variance Swaps and Forward Volatility Agreements

Variance swaps are the cleanest instrument for capturing the VRP.

Their payout is the difference between realized variance and implied variance (the strike).

Unlike options, they remove gamma and path dependency.

Forward volatility agreements (FVAs), used mostly by institutions, allow bets on implied volatility levels at future dates, targeting the term structure shape itself.

Both tools isolate and express the VRP without the complications of directional exposure or constant re-hedging.

Implementation in Practice: Options, Futures, and OTC Strategies

Harvesting the VRP in the real world involves a variety of instruments.

Each offer distinct exposures to implied volatility, realized volatility, and the term structure of volatility.

From retail-friendly option spreads to institutional-grade OTC derivatives, the implementation method a trader chooses defines not only the return potential but also the strategy’s risk profile and operational complexity.

Selling Options: The Most Direct Approach

The simplest way to capture the VRP is by selling options.

This strategy relies on the fact that implied volatility tends to exceed realized volatility, allowing the seller to keep the premium when the option expires worthless or is hedged profitably.

Common setups include:

- Short straddles (selling both a call and a put at the same strike) and

- Short strangles (selling out-of-the-money calls and puts for a wider range).

These are directionally neutral but carry unlimited risk in a large move.

They’re popular with experienced traders who monitor exposure closely and use active delta hedging.

Defined-Risk Spreads: Iron Condors and Credit Spreads

To control downside risk, many traders use defined-risk option structures.

An iron condor, for example, sells a call spread and a put spread simultaneously. It limits both upside and downside exposure while still capturing time decay and benefiting from falling volatility.

These trades offer lower premium collection but significantly reduced tail risk, making them ideal for accounts with capital constraints or limited margin flexibility.

VIX Futures and Roll Yield

Traders can also access volatility directly via VIX futures, which reflect the market’s forward-looking expectations of S&P 500 volatility.

The VIX term structure is usually in contango, where longer-dated contracts are priced higher than near-term ones.

Shorting VIX futures in this environment allows traders to capture roll yield as those contracts decay toward the spot VIX price.

However, during market stress, this curve can invert (backwardation), causing sharp losses for short positions.

Exchange-Traded Products (ETPs)

For broader accessibility, inverse VIX ETPs like SVXY (ProShares Short VIX Short-Term Futures ETF) package the short VIX futures strategy into a tradable fund.

These are convenient, but these products suffer from volatility drag due to daily rebalancing and are vulnerable to sharp market moves.

Their simplicity belies significant embedded risks.

They’re for day trading purposes only.

OTC Derivatives: Variance Swaps and Forward Volatility Agreements

Institutional players often prefer variance swaps and forward volatility agreements (FVAs).

These are more precise instruments for harvesting the VRP, allowing pure exposure to volatility without directional market risk or Greek sensitivities like gamma and theta.

They also eliminate the need for continuous rebalancing, making them ideal for passive VRP capture over longer horizons.

Navigating the Risks: Gamma, Vega, Tail Events, and Structural Crashes

While volatility carry strategies can produce steady returns, they come with a risk profile that is anything but ordinary.

These strategies are inherently asymmetric, with small, consistent gains are punctuated by rare but potentially catastrophic losses.

This is the nature of selling insurance: most of the time, nothing happens, but when it does, losses can be swift and severe.

Gamma and Vega Exposure

Short volatility strategies are almost always short gamma and short vega.

Being short gamma means losses accelerate as the market moves sharply in either direction.

Delta-hedging into a falling market involves selling into weakness, and in a rising market, it requires buying into strength. Both magnify losses.

Being short vega means that any sudden rise in implied volatility, even without a price move, can cause significant mark-to-market damage.

Tail Risk and the “Peso Problem”

The major danger lies in tail events. Sharp volatility spikes that the strategy isn’t positioned to withstand.

These events are rare but devastating.

Compounding the risk is the Peso Problem: strategies appear highly profitable for years, masking the hidden exposure to a rare crash that hasn’t occurred yet.

Volmageddon: A Case Study in Structural Failure

The risks became painfully real on February 5, 2018, known as “Volmageddon.”

In a single day, the VIX more than doubled, triggering massive losses in short volatility products.

The popular inverse VIX ETP XIV collapsed by over 90%, leading to its termination.

This wasn’t due to a major macro event, but was a self-reinforcing feedback loop caused by structural crowding, illiquidity, and leveraged products forced to rebalance during a volatility spike.

It was a reminder: in short vol strategies, risk often emerges not from fundamentals, but from the market’s own architecture.

Performance Through Time: Empirical Results and Market Regime Analysis

Empirical research shows that volatility carry strategies have delivered high risk-adjusted returns over long periods, but with deep caveats.

Academic studies using variance swaps and forward volatility agreements report Sharpe ratios as high as 3.0 to 4.0, outperforming traditional carry strategies in currencies or bonds.

However, this outperformance comes with severe negative skewness and exposure to tail events, making standard deviation an incomplete risk measure.

In calm, rising markets, volatility carry performs exceptionally well.

Implied volatility declines, options decay, and VIX futures roll yield compounds returns.

During these low-volatility regimes, carry strategies often appear uncorrelated with equities.

But in crisis periods (2008, 2020, or even short shocks like Volmageddon) correlations spike, realized volatility jumps, and short vol positions suffer rapid drawdowns.

Data from the CBOE Eurekahedge indices confirms this dynamic.

Long volatility funds shine during crises but bleed small amounts in stable markets (e.g., Universa).

Short volatility funds post strong returns during quiet periods but crash hard when volatility surges.

Relative value funds, which shift exposure dynamically, offer more balanced performance across regimes, highlighting the value of tactical positioning in volatility.

Strategic Role and Portfolio Integration: Applications for Sophisticated Investors

Volatility carry strategies can be both powerful and dangerous, which makes their role in a portfolio highly nuanced.

When used thoughtfully, they can act as a return enhancer, offering steady income streams that outperform many traditional asset classes on a risk-adjusted basis.

But unlike defensive or uncorrelated strategies, short volatility is pro-cyclical: it tends to perform well during periods of low stress and underperform catastrophically during market turmoil.

Not a Hedge, But a Complement

One common mistake is treating volatility carry as a hedge or diversifier.

In calm markets, it may appear uncorrelated to equities, but in crisis periods, that correlation often spikes.

Volatility carry behaves more like an equity-linked risk asset, with deep drawdowns when markets panic.

Therefore, it should never be seen as a standalone diversifier.

However, it can complement long volatility or tail risk strategies, which typically lose money in calm markets but surge during crises.

Symbiosis with Long Volatility Strategies

Combining short volatility (carry) and long volatility positions creates a more robust structure.

The carry leg provides income during normal periods, while the long volatility leg acts as insurance against tail events.

This pairing reduces net drawdowns, flattens the return distribution, and creates a more convex portfolio that can adapt across regimes.

Some sophisticated investors fund their long vol exposure entirely with proceeds from volatility carry, using one to offset the cost of the other.

Diversification Across Carry Sources

Volatility carry also benefits from being part of a multi-asset carry strategy.

Because carry trades across currencies, bonds, commodities, and volatility are only loosely correlated, a portfolio diversified across these dimensions can reduce overall skewness and improve Sharpe ratios.

A global carry basket balances different economic sensitivities, reducing dependence on any one market structure or regime.

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Sophisticated investors should be selective in how they implement volatility carry.

Retail-accessible tools like short straddles or inverse VIX ETPs are high-risk and operationally fragile.

Institutions often favor variance swaps, forward volatility agreements, or defined-risk option spreads like iron condors.

Position sizing, tail hedging, and constant monitoring for crowding and liquidity conditions are non-negotiable for survival.

In sum, volatility carry is not for the naive.

But when integrated properly (with risk controls, hedging overlays, and complementary exposures) it becomes a powerful tool for experienced investors looking to extract structural premiums from persistent behavioral inefficiencies in the market.