Hedge Funds Don’t Beat the Market – Is This a Bad Thing?

A common criticism of hedge funds is that they don’t beat the market (commonly taken as the S&P 500, which is the world’s most tracked equity benchmark).

Some even use this as a way to question why hedge funds exist in the first place. Namely, if something doesn’t add value, then shouldn’t natural forces do away with the ones that aren’t cutting it?

In 2008, Warren Buffett famously placed a million-dollar bet that an S&P 500 index fund would beat the funds of funds that hedge fund managers would select.

However, hedge funds as a whole shouldn’t be expected to beat the S&P.

We’ll explain why, as well as why comparisons to the S&P 500 usually don’t make much sense anyway in the context of hedge funds.

We’ll also cover why hedge funds beating the market isn’t necessarily good on its own either.

Key Takeaways – Hedge Funds Don’t Beat the Market

- Some hedge funds may underperform the broader market, but their primary value lies in their ability to provide diversification, manage risk, manage various types of objectives and requirements of their clients, and potentially improve overall portfolio performance when used appropriately.

- The job of a hedge fund is like any other business – to fulfill the goals of their clients – not to exceed arbitrary benchmarks.

- Beating the S&P 500 is one goal, but it’s far from the only goal.

- Very successful hedge funds tend to close to new investment or even transition into a family office and fall off the hedge fund radar. Less successful hedge funds are naturally weeded out.

- Hedge funds “beating the market” isn’t necessarily a good thing either if there’s high correlation to traditional equity and credit assets and is achieved through higher risk taken.

- “Beating the market” is irrelevant to many people’s goals.

- Ultimately, it isn’t about outperforming the market each year, but about building a strategy that consistently supports your long-term financial goals.

- In the end, it comes down to providing value.

Why “Beating the Market” Is an Oversimplification of Goals

Professional traders and investors are often misunderstood as simply trying to “beat the market” (an S&P 500 index fund or similar).

This view fails to capture the complexity and diversity of their actual roles.

Their primary function is to design customized strategies that align with specific client or institutional objectives.

These financial professionals specialize in:

Enhancing risk-adjusted performance

Traders aim to maximize returns relative to the level of risk taken, often using metrics like the Sharpe ratio, Sortino ratio, information ratio, among other customized risk-adjusted return metrics, to guide their strategy.

Diversifying portfolios through correlation management

By combining assets with low or negative correlations, traders can reduce overall portfolio volatility without necessarily sacrificing returns.

Implementing protective hedging strategies

Hedging involves taking offsetting positions to protect against adverse market movements, helping to limit potential losses.

Rather than necessarily driving their clients returns, they manage risk for them.

For example, if a company is selling a product overseas that brings currency risk, a financial professional can help them hedge out that risk.

If a company is selling a product dependent on commodity prices – where commodity price fluctuations can erode their margin and make it uneconomic to sell – a hedge fund can figure out strategies for them.

Balancing liquidity needs with return optimization

Professionals structure portfolios to make sure cash is available when needed while still seeking to maximize returns on invested capital.

A pension fund, endowment, or foundation would be an example.

Creating steady income streams

Strategies focusing on dividends, bonds, or other income-generating assets can provide regular cash flow for clients with specific income needs.

Maximizing after-tax returns

Tax-efficient investing strategies, such as tax-loss harvesting, asset location strategies, or using tax-advantaged accounts, can significantly improve net returns over time.

Synchronizing investments with future financial needs

Asset-liability management aligns investment horizons and risk profiles with anticipated future financial obligations or goals.

Identifying and capitalizing on market inefficiencies

Traders exploit pricing discrepancies or market anomalies to generate alpha, often using sophisticated analytical methods and algorithms.

Providing targeted exposure to various market segments

Customized portfolios can offer precise exposure to specific sectors, geographies, or asset classes based on a client’s investment thesis or needs.

Using various risk mitigation techniques

Risk management techniques, such as stop-loss orders, options strategies, asset allocation techniques, or dynamic asset allocation, help control and reduce various types of financial risk.

Supporting Long-term Wealth Preservation

For clients focused on wealth preservation over generations, professionals design strategies that prioritize stability, longevity, and protection against inflation and other erosive forces over time.

Enhancing Portfolio Agility

Financial professionals may use tactical asset allocation or actively manage portfolios to adapt quickly to whatever comes their way.

This allows for more responsive positioning and capital protection during volatile periods.

Facilitating Access to Alternative Investments

Some investors seek exposure to alternative assets like private equity, venture capital, real estate, or hedge funds.

Professionals manage these complex, often illiquid investments, which can provide diversification and uncorrelated returns to traditional assets.

For example, “fund of funds” specialize in this.

Tailoring Strategies for Specific Time Horizons

Investment professionals tailor portfolios to match various investment horizons, from short-term liquidity needs to long-term growth goals.

This ensures strategies align with each client’s unique time frame and financial objectives.

Overall

So while surpassing benchmark indices like the S&P 500 may be a goal for some strategies, it’s often not the main focus.

For example, a client may have the return objective of CPI + 500bps (i.e., a popular measure of inflation plus 5%).

Also, the client may specify a drawdown limitation of 20% from the high-water-mark plus no more than a 12% average annualized volatility.

In this case, this is a very different type of goal than simply getting whatever the S&P 500 provides.

Its risk management objectives are also specific and more restrictive than a stock index.

Overall, the real expertise of these professionals lies in crafting tailored financial solutions that address the various requirements and objectives of their clients or organizations.

This approach recognizes that success isn’t just about raw returns, but about achieving specific financial objectives while managing various constraints and risks.

By offering these specialized services, professional traders and investors provide value that goes far beyond the simplistic notion of market outperformance.

Alpha is zero sum

Alpha is a zero-sum game. If you deviate from the index in some way, then you’re making a bet that you’re right and somebody else is wrong.

You do this every time you pick stocks or try to pick winners and losers in a market. This is not easy to do because everything that’s known is already discounted in the price, so there are no easy sure things.

For example, we know that some companies are better than others. They earn more or they’re growing more. But because of how the discounting process works, this is already reflected in their valuations.

Moreover, there are transaction costs, overhead (e.g., staff, legal and compliance, etc.), and other fees that turn this into a negative-sum game.

So naturally, their performance will always lag the market to some degree. It’s simply in-built into the market structure.

The argument is like saying sports coaches as a whole don’t have a winning record. Does that mean we just shouldn’t have coaches? (And in market contexts, we shouldn’t have active managers and it’s pointless to pick individual stocks for your portfolio?)

It’s self-evident why sports coaches and managers don’t have winning records as a whole – they can’t.

Winning is a zero-sum game. When somebody wins, somebody else has to lose. So they can’t collectively produce a winning record. Yet there are a select few coaches (like investment firms and investment managers) who tend to be consistently better than others.

And how to attribute this outperformance (or underperformance) is not often easy to pin down.

- Is it simply because trading is a high-variance game and determining relative skill levels is not always easy or straightforward?

- Is it because they have talented people around them and they get carried along for the ride?

- Is it because of their own skill?

There are a group of hedge funds that are consistently very good.

And there are many that have no real edge as it pertains to whatever markets or form of business they engage in relative to a representative benchmark.

The problems with comparisons

If an LP (i.e., an investor) goes to a hedge fund and tells them they want 5 percent above inflation annually at no more than 12% annualized volatility (less than the S&P 500, which averages around 15% over the long run), and they consistently deliver on that promise – is it bad that they’re doing exactly what they said they would do even if the S&P is above that performance over recent market history?

If that were the goal, a “CPI + 500bps” mandate would return just 7 to 8 percent annualized when inflation is at a normal level.

7 to 8 percent will lag equity returns over some timeframes. So it will underperform something like the S&P 500 over certain market periods.

But if the strategy is executed successfully, they’re doing exactly what they said they were going to do at less risk than the benchmark.

So it’s not a very good or relevant comparison.

Risk is just as important as returns

One big component of returns is risk.

The average trader and investor thinks about returns, which is natural to do.

But sound risk management is very important. If you don’t play good defense, you’re going to blow too big of a hole in your portfolio – in the form of high drawdowns – that it’s going to be very hard to recover from.

If a firm is taking less risk in their investment style it’s likely they’ll underperform a strategy taking higher risk, even if their reward-to-risk (i.e., risk-adjusted returns) is superior.

The problem with the S&P as a benchmark

There’s also a problem with using the S&P as a benchmark, especially for firms that are not a long-only equities fund (like a mutual fund).

For example, if the S&P is down 30 percent and a hedge fund (or any type of trader) is down “only” 20 percent, is that great performance?

They might be beating the index by a wide margin but the performance is still objectively horrible.

And if the S&P is up 30 percent and you’re “only” up 20 percent, is that “bad” performance?

That’s very good performance irrespective of what the benchmark is doing.

Likewise, if you’re a landlord, you probably don’t care how your returns (e.g., net operating income divided by total cash invested into the properties) compare to the S&P 500.

You’re just trying to get what you can get and it’s not generally appropriate to compare your performance to the stock market.

Basically all businesses are “absolute return” vehicles.

There are other market indices

There are many other market indices outside the S&P 500.

For example, a long-only credit fund might be more appositely compared to a credit index rather than a stock index.

A Treasury bond fund might be better compared to a Treasury benchmark, and so on.

The importance of hedge fund size

It’s easier to make high returns off low sums of money than it is to make high returns off large sums of money.

There are lots of high-return, low-capacity opportunities in the market.

For example, small businesses tend to be run in a way that doesn’t necessarily maximize their return on investment.

On the other hand, there is lots of capital bidding up S&P 500 companies, which boosts their prices and lowers their forward returns.

It’s easier to create high returns on a $0-$10 million portfolio than it is in a portfolio of billions of dollars.

Things that are easy to do on a smaller scale are often not easy to do on a larger scale.

For example, many traders/investors are not able to trade smaller opportunities (e.g., small cap equities) because the size they need to transact in to make it worth it to them would move the market against them.

Not everything can be solved with passive investments

Different investors have different problems that can’t be solved through passive investments and need customized exposures.

In this case, it’s about solving their individuals problems and needs, not strictly about how does this part of our portfolio do against some other prepackaged product that some take to mean “the market.”

Some may require more customized solutions to meet their specific goals.

Hedge funds can provide this type of customized exposure, and therefore, not always beating the markets may not be a bad thing.

Example #1

For example, a pension fund may have certain liabilities that require specific types of investments to manage risk and generate returns.

Immunization and cash-flow matching strategies are important in such cases, so their returns match up with their liabilities.

Example #2

Or a high-net-worth individual may have unique tax or financial considerations that require specialized investment strategies.

Example #3

A multinational company may have a type of foreign exchange risk because they do business in various countries and emerging markets. Currency fluctuations – since they earn their income in the currency of those countries but have liabilities in their home currency (e.g., USD, EUR, GBP) – can significantly eat into their profit.

A hedge fund that specializes in currency management can help advise them on what to do.

In these cases, the goal of the hedge fund is not necessarily to beat the market, but rather to provide tailored solutions that meet the individual investor’s specific needs.

In fact, trying to beat the market may not even be the hedge fund’s objective.

Furthermore, passive investments may not be suitable for all types of market conditions.

During market downturns or volatile periods, passive investors may experience significant losses, whereas certain hedge funds may be better equipped to navigate these conditions (e.g., neutral or negative correlation to risk assets) and potentially even generate positive returns.

Timeframe considerations

Hedge funds can have different investment strategies that may not necessarily align with the goal of beating the market on a year-to-year basis.

Instead, some hedge funds may focus on managing risk and generating long-term returns, which may require sacrificing short-term gains.

For example, a hedge fund that specializes in hedging extreme tail risks may do certain trades (e.g., OTM put options) that may underperform in normal market conditions but may provide protection during extreme events such as market crashes.

In this case, the hedge fund may experience small losses during most years but may potentially make significant gains during market downturns due to the high convexity of the strategy.

Moreover, these types of hedge funds may have longer time horizons than traditional investors who are more focused on short-term gains.

By putting some amount of money in hedge funds that specialize in managing extreme tail risks, investors may benefit from the long-term risk management benefits that these investments can provide.

In addition, hedge funds that do not always beat the market may still offer valuable diversification benefits to investors.

They are often called “niche strategies.”

By investing in a hedge fund with a different investment strategy than traditional investments, investors may be able to reduce the overall risk of their portfolio and potentially generate positive returns.

Accordingly, while hedge funds not beating the market may seem counterintuitive, it’s important to consider the investment strategy and time horizon of the fund.

In some cases, a hedge fund that may underperform in the short term may still be a valuable addition to an investor’s portfolio, particularly for those with longer-term investment goals and risk management needs.

Hedge funds and differentiated returns streams

Moreover, having differentiated returns is a big component of alternative investment vehicles.

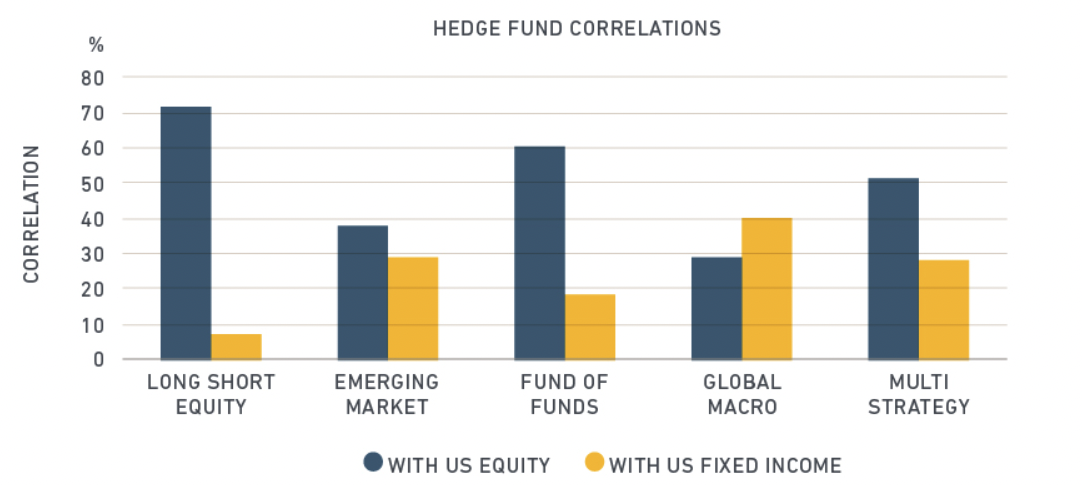

The average equities-focused hedge fund (and most hedge funds tend to focus on stocks) has a 0.70 or higher correlation with the stock market. This is very high for a returns stream that is supposed to be different.

Lack of differentiation and high correlation with other asset classes tends to be a bigger problem

(Source: MSCI)

If you go to a hedge fund and it’s almost the same thing as what you could get with a basic ETF – which is basically free – it largely defeats the purpose.

It’s hard to create alpha in the stock market, especially among large-cap equities, as it’s one of the most competitive markets out there.

Those who turn to hedge funds – e.g., pension funds, endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds, accredited investors – look toward them for a returns stream that isn’t correlated with their other investments or could even be a risk-off hedge.

How these investors evaluate alternative investment vehicles

When those types of investors evaluate funds, they aren’t looking at superficial criteria like its returns relative to the S&P 500.

They’re going to look at its returns in relation to:

- how much risk it’s taking as well as…

- its correlation to other investments in their portfolio.

Therefore, you’re not necessarily looking for S&P returns. You’re looking for a positive returns stream that’s truly differentiated in some way.

For example, if they identify a fund that offers 5 percent annualized returns at 8 percent volatility and has no correlation to their other investments, that’s going to add value even if it lags the S&P 500.

Moreover, if a pension fund determines that, for instance, they lack investments that will help them in environments when inflation is above expectation, they don’t care if such “inflation” investments lag the S&P 500 over time.

They are looking for a type of exposure that will help offset losses in other parts of their portfolio when such an environment arises to help raise their risk-adjusted returns and help smooth out their returns over time.

What if hedge funds beat the market?

This isn’t necessarily good either.

It is important to assess things in relation to the risk they take on as well as their correlation to other investments that their clients have.

If you want a foolproof method of beating the market you could simply buy a stock index (or whatever the index is) on leverage.

If a hedge fund is getting 2x the return of the S&P 500 but is taking 2x-3x the risk (i.e., run at 2x to 3x higher volatility) and is nearly 100 percent correlated to the S&P 500, is that a good thing?

There’s no real differentiation in this type of investment.

Anyone considering investing in this type of fund will need to be very careful.

Taking a lot of risk shouldn’t be conflated with adding value.

Just as not beating a representative benchmark should not be automatically equated to not adding value because it’s in relation to the risk they take on as well as their correlation to other types of investments.

Like many things, there is a lot of nuance involved.

Summary

This oversimplification about hedge funds subpar returns or failing to outperform a certain index as a whole fails to capture the nuanced reality of hedge fund performance and objectives.

Here’s a more accurate explanation:

Diverse objectives

Hedge funds have various trading/investment strategies and goals.

Not all try to outperform the stock market directly.

Many focus on providing uncorrelated returns or managing risk, which are valuable for portfolio diversification.

Survival bias

Underperforming hedge funds often close, leaving only the successful ones operating.

This means the industry naturally weeds out poor performers.

Performance measurement

Comparing hedge funds to broad market indices can be misleading.

Their performance should be evaluated based on their specific objectives and risk-adjusted returns.

If a hedge fund is achieving only 75% of the return of a representative index but doing so at half the risk, the risk-adjusted return is 50% better relative to the index (75%/50%).

Aggregate performance

When combined in an index, hedge funds typically show lower volatility than the stock market.

Market environments

In strongly bullish markets, hedge funds may underperform major indices.

However, this doesn’t necessarily indicate poor performance, as they often provide better downside protection.

Portfolio benefits

Including hedge funds in a diversified portfolio can potentially lower overall risk and improve long-term returns compared to a portfolio without alternative investments.

Individual assessment

Hedge funds should be evaluated individually or by category, rather than as a whole industry.

Contribution to portfolio

The key question isn’t whether a hedge fund outperforms the stock market, but whether including it in a portfolio improves the overall risk-adjusted return.

Final word

Hedge funds don’t beat the market as a whole, but they shouldn’t be expected to, given alpha is zero-sum and there are fees associated with doing business.

Hedge funds are fundamentally absolute return vehicles, not relative return vehicles, like a mutual fund typically is.

In the end, there is real value to investment firms, whatever label or designation one wants to put on them. Capital allocation is a very important part of an economy.

Bank, nonbanks, local governments, central governments, private nonfinancial companies, individuals, families, and so on, all have a role to play in this process.