How Does Warren Buffett Beat the Market?

If you ask 100 people who the world’s most successful investor is, probably over half of them (who give an answer) would say Warren Buffett.

The puzzle: is his success skill, luck, survivorship bias, or something explainable?

To answer this, we looked at an academic paper by Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Heje Pedersen (the former two were employed at AQR Capital Management at the time the study was published).

The study’s key finding: Buffett’s performance can be explained by modest leverage plus a disciplined focus on safe, cheap, high-quality stocks.

Key Takeaways – How Does Warren Buffett Beat the Market?

- Extraordinary returns over decades. Berkshire Hathaway outperformed the market by a wide margin, with higher returns per unit of risk than any mutual fund or stock of similar longevity.

- He endured losses. Buffett lost 44% during the dot-com bubble (and more in relative terms) and 40% in 2008, yet his refusal to abandon his strategy allowed compounding to continue.

- Leverage was important, but modest. Buffett used about 1.6-to-1 leverage, small by Wall Street standards, but powerful when applied safely over decades.

- His financing edge was unique. Insurance float, favorable debt, and tax deferrals gave him cheap, stable, and long-term leverage unavailable to most investors. This part is hard for the average investor to replicate.

- Public stocks outperformed private businesses. Buffett’s greatest returns came from his stock-picking, while his owned companies provided stability and financing.

- He bought three things at once:

- Safe companies with low volatility.

- Cheap companies trading below intrinsic value.

- High-quality companies with durable profits and growth.

- His strategy is systematic. When replicated with factor models (low risk, value, quality, and modest leverage), Buffett’s results can be explained, proving his edge was executing the same style repeatedly over a long period of time.

- Execution is everything. Knowing the formula isn’t enough. Buffett stuck with it for over 50 years, while others abandoned similar strategies during tough times.

Buffett’s Track Record

The Long Game Pays Off

When people talk about Warren Buffett, they often focus on his folksy wisdom, avuncular charm, or his knack for finding deals.

But the numbers tell a story that’s even more impressive.

If you had put a single dollar into Berkshire Hathaway in late 1976, by the end of 2011 you’d be sitting on more than $1,500. That’s not a typo.

Over those 35 years, Buffett delivered an average annual excess return of 19 percent above Treasury bills.

For comparison, the broad stock market managed just over 6 percent above T-bills in the same period.

What makes this more remarkable is the consistency. Berkshire Hathaway wasn’t a tech rocketship that soared for a few years and fizzled out.

It compounded steadily over decades, weathering recessions, crashes, bubbles, and many panicky periods along the way.

That kind of endurance is what turned Buffett from a successful investor into one of the richest people alive.

Standing Above the Rest

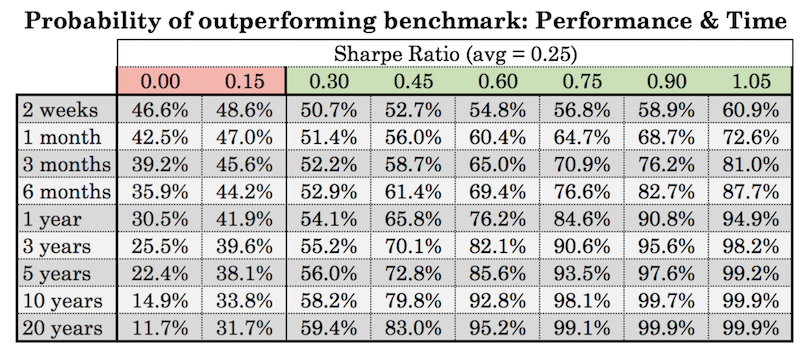

To see how unusual this is, consider the yardstick professionals use: the Sharpe ratio, which measures return against risk. Most traders and investors struggle to maintain anything above 0.4 over the long run.

Berkshire Hathaway sits at 0.76.

That might not sound flashy, but it’s the highest of any stock with more than 30 years of history. It also tops every US mutual fund of similar age.

In plain terms, Buffett wasn’t just making money. He was making more money per unit of risk than anyone else for decades.

And he did it in a way that others rarely sustained. Mutual funds come and go. Managers rise and fall. Berkshire kept compounding.

Surviving the Tough Times

Of course, Buffett’s ride wasn’t smooth. One of his biggest tests came during the internet bubble.

From mid-1998 to early 2000, Berkshire lost 44 percent of its market value. It was “old economy.”

At the same time, the overall market, driven by the “new economy” stocks, was up more than 30 percent.

Imagine being down almost half your wealth while everyone else around you is celebrating triple-digit dot-com gains.

Most managers would have cracked. Investors would have pulled their money, reputations would have shattered, and careers would have ended.

Julian Robertson of Tiger Management famously threw in the towel in March 2000 – incidentally at the very top of the market.

But Buffett had built something different.

His reputation and Berkshire’s structure let him stay the course.

When the bubble finally burst, Berkshire bounced back, proving that patience, and conviction, can be as valuable as picking the right stock.

Why It Matters

Buffett has a quote where he says the first rule of investing is to not lose money.

And the second rule is to remember rule number one.

The thing is that he’s actually lost plenty, including around 40% in 2008.

That said, he refused to abandon his strategy when it mattered most. That ability to endure rough years without blinking may be the real secret to his extraordinary results.

Warren Buffett’s First Television Interview – Discussing Timeless Investment Principles

Outside a brief 1962 filmed statement, this 1985 interview from his office in Omaha is believed to be his first televised interview.

Key points:

- The most important quality for an investment manager is their temperament, not their intellect. He says you don’t need a high IQ to be a successful investor. You need a stable personality that doesn’t get swayed by the crowd. It doesn’t matter if people agree or disagree with you, but whether the quality of your reasoning is solid.

- Think of yourself as owning a piece of a business, not just a stock. Most professional investors make the mistake of focusing on what a stock will do in the next year or two.

- He doesn’t pay attention to day-to-day fluctuations of the market. Buffett says the stock market could close down for five years, and it wouldn’t bother him.

- Buffett doesn’t own any technology companies because he doesn’t understand them. He only invests in businesses that he’s competent to value.

The Role of Leverage

A Quiet Engine Behind the Returns

Buffett is often celebrated as the ultimate stock picker, but there’s another ingredient in his success that rarely makes headlines: leverage.

On average, Berkshire Hathaway has operated with about 1.6-to-1 leverage. In simple terms, for every dollar of equity, Buffett controlled $1.60 worth of assets.

That doesn’t sound extreme compared to many hedge funds – and Berkshire is not a hedge fund – which sometimes run far higher.

But applied steadily over decades, with the right kind of assets, it made a huge difference.

Leverage boosted both Berkshire’s gains and its risks. If the market handed Buffett a good year, leverage made it even better. If things went sour, losses stung more sharply.

The idea wasn’t just using leverage. It was finding a way to use it safely and cheaply, without being forced into fire sales when markets turned.

Where the Money Came From

Most investors borrow at steep costs. Buffett, instead, tapped into unique sources of financing that gave him a built-in advantage.

Debt

First was debt, which Berkshire could issue at unusually favorable terms thanks to its rock-solid reputation.

For two decades, the company even carried a AAA credit rating, the highest possible.

Some AAA bonds have even traded at a negative premium to US Treasuries.

Insurance Float

Second, and more importantly, was insurance float. Insurance companies collect premiums upfront and pay claims later.

In the meantime, they hold the money, effectively borrowing from policyholders.

For most insurers, this float comes with a cost, because underwriting losses eat away at returns. Buffett built Berkshire’s insurance businesses, like GEICO and reinsurance units, so well that the float often came with little or no cost.

Over decades, this gave him tens of billions in capital to invest at rates below Treasury bills. That’s like having a standing line of credit cheaper than the US government’s borrowing costs.

For individual traders/investors, they’re usually paying Treasury rates, plus a spread of several percentage points.

Tax Timing

Third, Berkshire benefited from tax timing advantages, such as accelerated depreciation rules.

These acted like interest-free loans from the government, pushing tax payments into the future and freeing up more cash to invest in the present.

Power and Peril

Leverage alone doesn’t explain Buffett’s results, but it magnified them.

If the market earned about 6% above Treasury bills, 1.6-to-1 leverage would have boosted that to roughly 10%.

That’s still far short of Berkshire’s 19% average excess return.

But combined with his knack for buying safe, cheap, high-quality businesses, leverage turned very good results into spectacular ones.

So, it wasn’t just using borrowed money. It was in building a system where financing was permanent, cheap, and stable, so he never had to sell or doing anything inefficient when markets crashed.

That patience with leverage is something few investors can match.

Public vs. Private Investments

Two Sides of the Same Coin

Berkshire Hathaway isn’t just a portfolio of stocks, but a collection of entire businesses that Buffett bought outright: railroads, insurers, utilities, and consumer companies.

To understand where his returns really came from, it helps to separate these two buckets (public stocks and private companies) and see which one carried more of the weight.

The surprising answer?

Buffett’s portfolio of publicly traded stocks performed better than his wholly owned companies.

His private businesses generated strong profits and helped make Berkshire a fortress. But when researchers crunched the numbers, the edge leaned toward his/Berkshire’s stock picks.

The Stock Picker at Work

From Coca-Cola to American Express to Wells Fargo, Buffett’s biggest wins came in the public markets. The stocks he chose consistently outperformed the broader market, even after adjusting for risk.

And they did it in a way that lined up with his philosophy: he wasn’t chasing fads or momentum, he was buying companies that were stable, profitable, and undervalued.

This matters because it answers a long-standing debate: is Buffett’s magic in running businesses or in picking them? The evidence tilts heavily toward the latter.

He is, at his core, an investor.

His ability to identify businesses worth holding for decades, and then actually hold them, was the primary driver of Berkshire’s edge.

Why Own Businesses at All?

If his stock portfolio was the star, why spend so much time buying whole companies? The answer lies in financing.

Berkshire’s private businesses, especially its insurance subsidiaries, provided a steady stream of cash and, more importantly, a reliable source of float.

This float acted as low-cost leverage, which in turn powered his stock picks.

Take the insurance units. They generated billions in premiums each year that Buffett could put to work long before claims were due.

Because these businesses were well run, the float didn’t cost Berkshire much, often nothing at all.

That gave Buffett access to a type of capital that most investors can only dream of: cheap, patient money.

Beyond insurance, other subsidiaries created stability. Owning railroads, utilities, and consumer businesses made Berkshire less vulnerable to market swings.

This meant Buffett could take bolder positions in the stock market without worrying that a downturn would sink the ship.

The Balance Over Time

Early in Buffett’s career, Berkshire leaned more on public stocks.

In the 1980s, less than 20 percent of Berkshire’s assets were tied up in private companies.

By 2011, that share had climbed to more than 80 percent.

This shift reflects both Berkshire’s sheer size* and Buffett’s desire for permanent sources of capital.

Still, even with this shift, the data shows that public stocks were the stronger performers on a risk-adjusted basis.

The private businesses added diversification, cash flow, and financing advantages, but the pure outperformance came from Buffett’s knack for buying the right public companies.

___

* It becomes harder to put massive sums into the stock market alone without incurring larger transaction costs (they tend to get bigger the more you manage). Also, the bigger you get, the smaller the universe of stocks available to you becomes for liquidity/transaction cost reasons.

What It Tells Us

His stock-picking made the money. His private businesses funded the strategy and kept it stable.

It’s the combination that mattered.

Without the float and steady earnings of his wholly owned firms, Berkshire couldn’t have leveraged safely.

Without Buffett’s eye for stocks, the float would have gone to waste.

The lesson for traders and investors is clear: great returns aren’t just about picking winners, and they’re not just about access to capital.

They come from marrying the two: skill in selection with a structure that makes that skill scalable and resilient.

Buffett built both halves, and that’s why his machine kept compounding when others fell apart.

It’s also something that’s replicable.

Let’s say someone owns a small business. That gives them a flow of steady funding, which can then be put into liquid investments that earn independently.

What Kind of Stocks Does Buffett Buy?

More Than Just “Value”

Ask most financial people what Warren Buffett looks for in a stock and they’ll say “value.”

That’s true, but it’s not the full story.

In fact, some of his best-known quotes warn against “buying fair companies at wonderful prices.”

Instead, Buffett’s edge has been about finding three qualities at once: safe, cheap, and high-quality.

When you put those pieces together, you start to see the real pattern behind his picks.

Safe: Betting Against Risk

Buffett has always had a preference for what finance academics call low-beta stocks.

These are companies whose prices don’t swing wildly when the market goes up or down. Think of them as the sturdy ships in a storm. They may not surge ahead as fast as high-flying tech startups during a boom, but they also don’t have a high failure rate.

Think of the stuff that we all buy. Food, basic medicine, utilities (water, electricity)… Many people don’t go to the movies, don’t buy expensive cars, maybe don’t go to restaurants. Those are more discretionary. But basically everyone buys the staples to physically live.

Most investors overlook these kinds of companies because they seem “boring.” They’re not glamorous, they don’t make headlines, and they don’t promise overnight riches. But boring is exactly what Buffett likes.

Low-risk companies allow him to control risk and, more importantly, to apply leverage safely.

Amplifying the returns of already stable businesses, Buffett could boost performance without taking on risk he’s not comfortable with and businesses he doesn’t fully trust to stand the test of time or understand.

Cheap: Classic Value Investing

The second ingredient is cheapness. But not in the sense of bargain-bin shopping. Buffett looks for companies with low price-to-book or price-to-earnings ratios, relative to their true potential.

These are the kinds of businesses Benjamin Graham, his teacher at Columbia, wrote about in the 1930s.

Think about Coca-Cola in the late 1980s. At the time, it wasn’t a hot new stock. It was a century-old soda company.

But Buffett recognized its brand power, global reach, and stable cash flow, and he bought heavily. The price he paid looked modest relative to the company’s long-term prospects, making it a textbook value play.

This “cheap but good” approach stands in sharp contrast to the speculative mindset that often dominates markets.

While others chase stories and trends, Buffett has consistently chosen companies that are priced fairly or cheaply compared to their fundamentals.

High-Quality: Strong Companies at Fair Prices

If safety and value were the only factors, you could almost automate the strategy.

But Buffett’s third filter (quality) adds the human judgment that makes his approach harder to copy.

What does he mean by quality?

Companies that are profitable, generate consistent cash flows, grow steadily, and return capital to shareholders through dividends or buybacks.

In other words, businesses that can stand the test of time.

American Express is a good example. Buffett first bought it during a crisis in the 1960s, when the company was struggling with a scandal.

It was cheap and relatively safe, but it was also a brand with a moat – i.e., a competitive edge that kept customers loyal. Decades later, it remains one of Berkshire’s core holdings.

How This Shows Up in the Data

When researchers analyzed Buffett’s portfolio, they found it consistently loaded on two key factors: Betting Against Beta (BAB) and Quality Minus Junk (QMJ).

- BAB reflects the preference for safe, low-volatility stocks.

- QMJ captures the tilt toward high-quality companies over unstable, “junk” firms.

Add in a clear bias toward value, and you get the full Buffett recipe.

The finding was this: once you account for these factors, Buffett’s legendary “alpha” largely disappears.

In other words, his performance wasn’t luck or something abstruse.

It was the result of sticking to a systematic set of principles (safe, cheap, high-quality) applied with consistency.

The Discipline Behind the Picks

Of course, just knowing these principles isn’t enough. Many investors are aware of value, safety, and quality as ideas.

Few actually have the patience to buy and hold such companies for decades. Buffett did.

He didn’t chase tech bubbles, he didn’t panic during crashes, and he didn’t abandon his playbook when it looked old-fashioned.

That discipline, more than any single stock, is what sets him apart.

It’s easy to admire Coca-Cola or American Express in hindsight. What’s harder is having the conviction to buy them when they’re unloved, and then refusing to sell when the crowd insists you’re wrong.

A Lesson for the Rest of Us

So what kind of stocks does Buffett buy?

The kind that don’t always feel exciting in the moment but compound quietly over time.

Safe. Cheap. High-quality.

It’s a deceptively simple formula, one that requires more patience than brilliance.

And that, perhaps, is Buffett’s real genius. Not inventing a secret strategy, but committing to one that he could follow, based on his particular business model.

A Systematic Buffett Strategy

Can You Copy Buffett?

If Buffett’s success comes down to buying safe, cheap, high-quality stocks with a dash of leverage, then a natural question follows: could anyone simply copy the formula?

The researchers we referenced in the intro put this to the test by building what they called systematic Buffett-style portfolios.

Instead of handpicking companies, they used data screens to mimic the traits Buffett consistently sought: low-risk, value-oriented, high-quality firms.

They then added leverage to match Berkshire’s risk profile.

The idea was to strip out Buffett’s personal judgment and see whether the raw strategy alone could explain his results.

What the Tests Showed

The results were striking. These simulated portfolios delivered performance very similar to Berkshire Hathaway’s, both in terms of returns and risk-adjusted metrics.

In fact, the correlation between Buffett’s real-life stock portfolio and the systematic version was about 75 percent.

That doesn’t mean the exercise was perfect. The backtests benefited from hindsight and didn’t account for real-world frictions like transaction costs or taxes.

Still, the close alignment suggested something important: Buffett’s returns were replicable, at least in principle, by applying a disciplined, factor-based approach.

The Buffett Difference

So why doesn’t everyone do it? The answer lies less in the formula and more in the execution.

Buffett started applying this approach in the 1960s, long before finance professors and market practitioners had even named the factors.

He found ways to finance his bets cheaply, often through insurance float, and, most critically, he stuck with the strategy for ~60 years.

A fun fact is that Buffett has made 99.9% of his wealth after the age of 50.

Sticking with something for 60+ years is where most investors stumble. A systematic Buffett portfolio will look painfully out of step during booms in growth or momentum stocks.

It requires the kind of patience, confidence, and organizational structure that few can muster.

In short, yes, the Buffett playbook can be copied on paper. Living with it through thick and thin, as Buffett did, is what makes it legendary.

Lessons for Investors

1. Patience and Temperament Beats Brilliance

Buffett’s biggest edge wasn’t intelligence, but patience and a stable temperament.

He stuck with his strategy through decades of market noise.

Most investors can’t resist chasing trends or what’s hot.

2. Focus on Quality

Buying “junk” companies because they look cheap often backfires.

Buffett showed that paying a fair price for a great business is far better than snagging a weak company at a bargain.

3. Value Still Matters

Trendy growth stocks come and go, but value (companies priced below their true worth) remains a reliable anchor.

Buffett never stopped being a value investor, just a refined one.

4. Safety Is an Asset

Low-risk companies may feel boring, but they can quietly deliver excellent results. Safe stocks paired with leverage gave Buffett smoother, compounding returns.

5. Use Leverage Carefully

Leverage can magnify both gains and losses. Buffett used it modestly (as mentioned, around 1.6-to-1) and only because his financing was cheap and stable.

For most people, reckless borrowing is a shortcut to ruin.

6. Build Durable Financing

Buffett’s insurance float gave him permanent, low-cost capital.

Individual traders and investors don’t have that option, but the lesson is to avoid fragile funding.

Never invest with money you might be forced to pull out in a downturn.

7. Think Decades, Not Months

Buffett’s biggest wins (Coca-Cola, American Express, GEICO) played out over decades.

If you can’t hold through bad years, you’ll never see the power of compounding.

8. Ignore the Crowd

In 1999, Buffett was mocked for missing the tech boom.

A year later, most dot-com darlings had collapsed while Berkshire endured.

Following the herd is rarely the path to lasting wealth.

9. Structure Matters

Buffett’s mix of public and private businesses let him ride out storms.

For regular investors, diversification across assets and income sources can create the same resilience.

10. Keep It Simple

Buffett’s strategy boils down to safe, cheap, high-quality businesses.

The discipline to keep it simple is rare, and that’s a big part of why it works.

11. Embrace Drawdowns

Like we talked about when we began this article, even Buffett lost big at times.

Berkshire underperformed during the internet bubble while the market soared.

The key was surviving those stretches without abandoning his approach.

Earnings and cash flow are timeless.

12. Consistency Creates Compounding

Buffett didn’t reinvent himself every few years. He refined his approach but kept the same core principles for decades.

That consistency let compounding work its quiet magic, turning good annual returns into extraordinary lifetime wealth.

13. Stocks = Fractional Ownership of Businesses

Stocks aren’t numbers that move on a screen.

They’re ownership in businesses.

Buffett once said that if stock prices drop, he’d be more likely to buy more, just as a farmer might happily purchase additional farmland if it suddenly sold for less, as the earnings come cheaper.

Conclusion

Warren Buffett’s success isn’t a riddle. He bought safe, cheap, high-quality businesses, applied modest leverage, and held on with extraordinary patience.

His genius was less about discovering secrets than about refusing to abandon simple truths when others lost faith.

The lesson is both humbling and hopeful: you don’t need a secret formula to build lasting wealth.

Just discipline, structure, and time.