Lumber Market: Supply, Demand, and Big Picture Influences

Lumber and other wood products went up massively in the early 2020s for various reasons. Many were related to the unique supply and demand parts of the market. Others were related to the monetary environment.

We’ll put together the factors driving its movement, and also look at how this can impact other commodity markets that are tied to its most prominent end-product supply chains.

Supply and Demand

In terms of the supply and demand picture, homebuilders are notably trying to make up for lost time. The US is short close to 4 million single-family homes.

The tight home supply is still part of the lasting legacy from the 2008 housing crisis.

Homebuilders recognize this and have caused building permits to move higher.

Lower short-term and long-term interest rates on Treasury securities feed into other rates in the economy. Low mortgage rates are stimulating extra demand. Plus there’s been additional money from the government checks and programs.

And more people want houses, in general. They often bigger homes so they have space to work, now that many people have more flexible working arrangements.

This can mean renovations to existing housing stock, new housing, or higher prices on existing housing, which stimulates additional demand to build, and so on. All require lumber and wood products.

Considering housing as an asset itself, the monthly principal and interest payment isn’t too high with where the mortgage rate is. So it’s the down payment that’s the limiting factor for people when it comes to housing.

Canadian lumber is also subject to tariffs, which has benefited US suppliers and is a small piece of the equation.

Monetary influences

When cash and bonds yield negatively in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms they’re not attractive to hold. That money is probably increasingly going to want to move somewhere else.

So that’s good for commodities as a whole just in terms of speculative flows.

People view commodities as an alternative store of wealth. Commodities are priced as a certain amount of money per barrel, board feet, bushels, ounce, or some other quantity.

When the value of money goes down because the yield on it is poor and they’re creating a lot of it, the value of money goes down in commodity terms and the value of the commodity goes up in money terms.

With something like gold, because of its limited industrial use, it functions more like a long-duration store of value asset.

Its value has very little to do with the actual use of gold. Its utility doesn’t really go up much over time. Rather it’s simply reflective of the value of the money used to buy it.

Gold’s performance is always relative to a reference currency. It’s priced as a certain amount of dollars per ounce, euros per ounce, pounds per ounce, and so forth.

That’s why it can perform well relative to certain currencies and perform poorly relative to others. It’s a type of currency hedge, essentially functioning as a form of contra-currency, or the inverse of money.

It often performs inversely relative to one’s domestic currency. Many market participants like to hold it in a smaller quantity for this reason when they have so much of their wealth tied up in a single currency (maybe 5-10 percent of a portfolio can be prudent). And it can perform as a store of value on its, not only a currency hedge.

Other commodities can hold the same purpose to an extent.

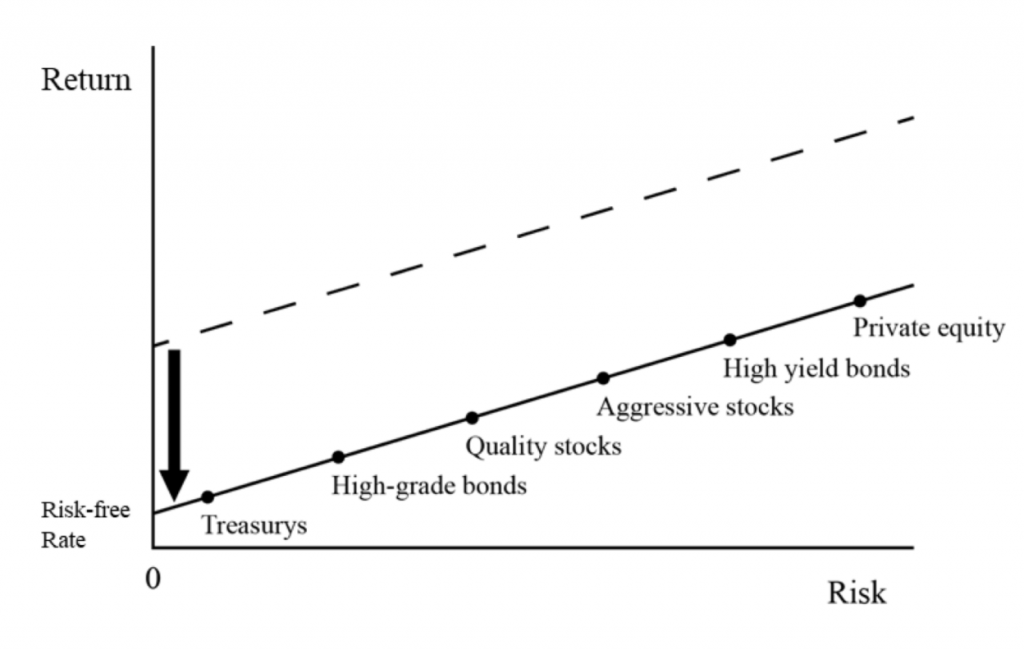

When you push down interest rates on cash and bonds, it brings down the yield of everything else beyond that on the risk curve – stocks, real estate, private equity – and pushes investors to look for other stuff that’s going to hold its purchasing power at a minimum.

Commodities don’t have an explicit yield on them, as a yield is typically advertised on cash and bonds, and can be backed out from earnings relative to price with respect to stocks.

But the lack of (outright) yield doesn’t matter when there’s a drop in the yields of everything else. This makes commodities more attractive to own in relative terms.

(Since 1850, owning commodities has yielded about 1.5 percent annually in real terms.)

The reach for yield in housing

Lumber feeds into housing, which can then be used to sell the units or rent them out to make income. Real estate is essentially a form of equity, reflecting ownership in a cash-producing asset.

With the yields so poor on cash and bonds – sources of wealth destruction – and the yields on stocks so compressed, a lot of larger investors are now buying homes with the intent of renting them out.

It’s a more active investment and more difficult to do, but it’s an absolute return type of game.

The lumber to build a regular single-family home of around 2,000 square feet is typically about 15,000 board feet and 6,000 square feet of structural panels (like plywood).

Normally this amount of lumber would cost around $10,000. If prices are 3x to 4x their normal value, then you’re up to $30,000 to $40,000 in costs.

This isn’t bad for the homebuilder so long as the price of rents and home sales go up to remain at least neutral on the yield.

In late March and early April of 2020, lumber was going for around $260 per 1000 board feet. In terms of how much that equates to in building a 2,000-square-foot house, if you locked in that price your lumber costs might be around $6,500. If the price goes up 5x, then it’s around $32,500.

And because the liquidity wave caused all boats to rise, everything else in the housing supply chain went up as well.

For example, crude oil feeds into the cost of flooring, roof shingles, drain pipe, and paint. Copper is used for conducting electricity and carrying water. Other commodity and product markets increased in price, including granite, ceramic tiles, drywall, concrete blocks, PVC, insulation, and others.

If the price of the home or the rent increases for the homebuilder, home seller, landlord, or investor, it’s not bad. But there’s also the lead time that presents a risk and it can present a strain on cash flow.

High prices curing high prices?

All commodities go through a cycle. There’s a saying in commodity markets that high prices cure high prices and low prices cure low prices.

In other words, when the price goes up, more producers want a cut of the market because it’s more profitable to produce it. As a result, they start to increase the capacity at which the commodity is produced.

Eventually supply exceeds demand, which causes prices to fall.

When low prices take effect, the same thing happens in reverse. If it’s not economical, people stop producing it. This is like lumber and many wood products and commodities in March 2020 and the short period following it. Oil even went negative.

People stop producing it or will engage in unusual behavior – such as oil cargo ships sitting in the harbor refusing to unload oil until the price goes back up.

The excess supply washes out of the market and prices begin rising again.

Moreover, at the same time, even as the underlying conditions change in markets, there’s a tendency for the past to get extrapolated. This commonly causes overshoots in price relative to the underlying fundamentals at both the lows and highs.

The basics

The price of something is simply the total amount spent divided by the quantity.

With the amount of liquidity that’s been put into the economy to recover from the virus combined with the unique supply and demand dynamics of the lumber market, getting such a large spike in price isn’t surprising.

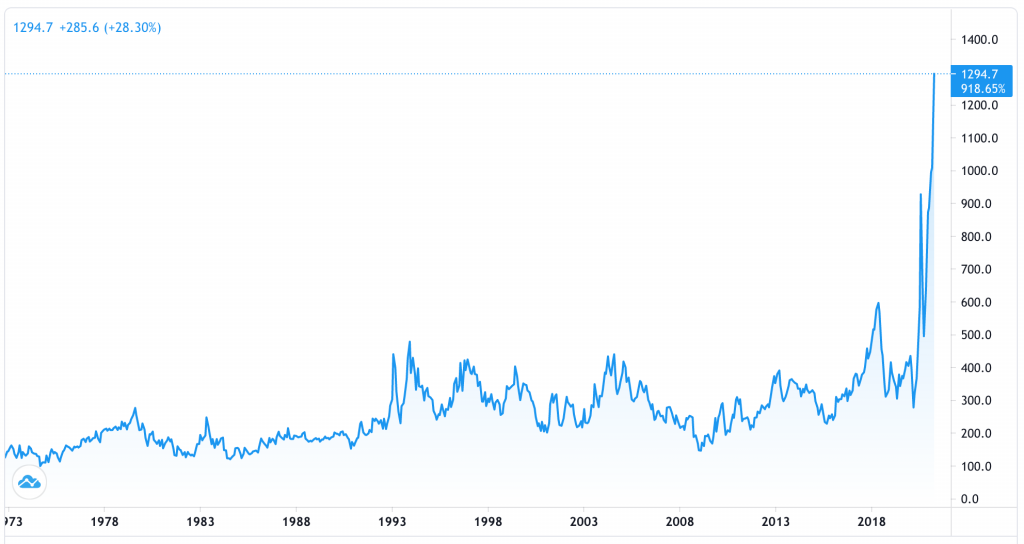

Going back to 1972, it’s the highest price ever by a large margin and more than 3x what it usually is.

Random Length Lumber Futures (GLOBEX: LB) going back to 1972

(Source: Trading View)

(Source: Trading View)

The futures market, based on the term structure, is pricing in an overshoot. But markets can stay high or low for elongated periods.

It’s dangerous shorting an overpriced market. Puts or put spreads can be a better strategy to give the upside without the unacceptable downside if the market keeps getting pricier.

The log-lumber divergence

Most of the US’s logs are harvested in the Southern US. But what’s been good for sawmills, including many of those bought up by Canadian firms trying to hop tariffs, hasn’t been good for timber growers.

There’s a log and lumber divergence.

Sawmills have largely been running to capacity and haven’t been able to keep up with lumber demand.

But so many trees have been planted in the Southeastern US to Texas that mills are paying low prices for logs – the lowest in 2-3 decades in nominal terms and back even further in inflation-adjusted terms.

And with standing pine, there are long lead times between current demand among existing facilities and new mills coming online and when enough trees are cut to balance supply with demand.

The virus-related lockdowns seemed to put a crimp in the ongoing housing recovery. Lumber fell and dealers liquidated their inventory.

Traders dropped their long bets on lumber futures and went short, betting that the fall would persist. Sawmills laid off workers and cut production, sometimes entirely.

But all this added up to a shortfall in lumber and wood when a surge in remodeling activity began with people staying home and restaurants wanting new outdoor places to seat customers.

Housing picked up after. Sawmills called back workers and ramped up capacity. But they couldn’t keep pace. Lumber became the US’s hottest commodity market in 2020-21.

Normally in the homebuilding space there’s a winter slowdown. But homebuilders kept pushing through.

While lumber hit record highs, the price of timber never recovered from its 2007 highs heading into the housing bust. Logs for softwood lumber averaged less than $23 per ton across the Southern US in the summer of 2020, the lowest in at least 28 years, not adjusted for inflation.

Timberland rotation

Pine wood takes roughly 25 years to raise before it can be suitable for lumber. That means only about four percent of the land generates income each year for landowners. At the same time, property taxes apply to the entire land acreage.

In Georgia, approximately one-third of the land is owned by individuals, families, and entities who use it to generate income.

Many of these businesses began back in the 1700s. British colonists used large timbers for ship masts. Gummy sap was used to produce turpentine. After the US declared independence from the British Empire in 1776, the Georgia legislature began offering settlers 500 acres if they built sawmills.

Pine also has the advantage of being a relatively hands-off business, compared to crops like cotton and nuts.

Forestation initiatives and carbon offsets

In today’s age, the federal government is heavily involved in the market, adjusting incentives to get the type of results it wants. Forestation initiatives – planting trees in exchange for annual compensation from the government – were designed to help stop erosion and ensure ample crop supply.

Companies like Microsoft and Royal Dutch Shell are paying timberland owners to keep trees standing in an effort to offset carbon emissions.

Post-2007

When home prices crashed in 2007 and later crashed the economy, lumber and timber fell as well. Sawmills in the Southern US had already been on the decline due to efforts to consolidate.

With the steep drop in housing construction, smaller mills were particularly hit hard. Efforts to consolidate ramped up further. Around 40 percent of all sawmills closed between 2000 and 2021, from around 400 to 250.

Pre-2008, Canadian mills began buying up mills in the Southern US. This helped avoid paying tariffs on lumber sold across the US border.

The southern states also have a more dynamic housing market than the north. As the nation gets older, more retire down south. State taxes are also generally more favorable in southern states compared to the north. Workers are cheaper as well.

On top of that, there’s a diversification element involved. Canadian forests commonly face issues with beetles that can rot wood supply and forest fires are common. Both factors can destroy tens of millions of acres of forest.

New government programs such as carbon offsets are one option for current timber producers. This initiative pays farmers not to fell trees, and incentivizes farmers to plant longleaf instead of faster-growing variants for habitat preservation and restoration purposes.

Timberland owners get a check from the government as long as their trees remain standing.

After these subsidies expire, needles can also be sold to landscape companies. An acre of pine straw can go from anywhere from $250-$350 per acre per year.

Companies can buy offsets to get rid of emissions from carbon ledgers to show investors, customers, and regulators that they are working to reduce the second-order effects of their activity (pollution, climate impacts).

The carbon offset market was engineered by SilviaTerra. This will expand from Southern pine to hardwood forests as well as to woods further up north.

How are the quantity and price of carbon offsets determined?

SilviaTerra uses satellite photography, computer programs, and forest surveys to determine a quality estimate of how much carbon the trees can essentially sponge out of the atmosphere.

That then determines how many credits owners can use to sell.

The price is determined at auction. Timberland owners find what a carbon offset is worth by knowing the price it would take to keep them from cutting the tree.

There are also logging and trucking costs to take into consideration for landowners. SilviaTerra can tell an owner how many carbon offsets one can sell based on the volume of trees they have available.

If a carbon sale is more economical than cutting, the landowner can take the carbon offset credit instead and use it to pay expenses associated with owning the land (and potentially have free cash flow). The trees can then be left for a future harvest period.