Are Real Estate & Primary Residences Good Investments?

Real estate is one of those investment asset classes that everyone has to do deal with. We always need somewhere to live. So that usually means renting or buying at some point.

Real estate and housing is at a unique point stage currently because of the debt and money creation going on in developed markets.

Does this make real estate an attractive investment?

Is a primary residence a good investment?

In this article, we’ll look at the argument.

The backdrop of the enormous creation of debt and money issue

Currently, we are seeing the debt and money creation issue play out classically, in the same way that it’s transpired many times throughout history, with the same mechanics driving how this is playing out now.

Specifically, because the amounts of money and credit that were created were much greater than the increases in goods, services, and investment assets, the prices of debt and money went down – i.e., they devalued – relative to the prices of goods, services, and financial assets.

As a result, we see inflation in goods, services, and investment assets and there are rising interest rates, so there is an ongoing squeeze in purchasing power that is coming from both ends.

It is consistent with the paradigm shift that is likely to be with us for most of the coming years.

This higher inflation and higher interest rates aren’t only market and economic issues. They are also domestic political and international geopolitical influences as they affect domestic politics.

Moreover, world economic growth and the strength of the US dollar as a reserve currency impact international geopolitics.

As we’ve covered in other articles, for a currency to be effective it has to function well as both a medium of exchange and as a reliable store of value.

Currencies are held in the form of debt (bonds, often as fixed-rate credit assets) and money (cash).

So when the buying power of currencies falls faster than is being compensated by the interest rates or rates of return on them – which is now the case in most currencies, debts, and money – their value as stores of value declines.

Beyond just the domestic issues of high inflation, low interest rates relative to inflation, and negative real returns, is the ongoing weaponization of the dollar through sanctions.

The weaponization issue is risky because those holding dollar-denominated debt (especially those with lots of geopolitical risk with the US, such as China and Russia) have to worry about being sanctioned.

This causes them to want to diversify away from the US dollar system and pursue other defensive maneuvers that weaken the unique power that the United States has.

Additionally, this prospect of weakening could lead to the selling of the dollar, which would be bearish for both the dollar and US bonds/credit, leading to a further rise in interest rates that could mean economic weakness.

Typically, this leads central banks to print money and buy their own debt – i.e., debt monetization – in order to ward off this economic weakness in exchange for currency devaluation (relative to goods, services, and investment assets).

In other words, the US’ unique power and privilege of having the world’s dominant reserve currency could be threatened by both its weakening through the creation of a lot of debt and money and the fear that others have of holding it for geopolitical reasons.

‘Devaluation’ of a currency

When talking about the “devaluation” of a currency, this doesn’t necessarily mean devaluation relative to other national currencies. They mostly move together. You do see major rises and falls of national currencies against each other, but they are not common.

What it typically means is that the value of money goes down relative to goods, services, and investment assets, making their prices go up in money terms and the value of money go down in terms of the value of those things.

Nominal vs. real wealth gains

In real estate, when we talk about “home prices are going up” it’s very important to differentiate between nominal and real wealth gains and to factor in things like carrying costs, which are very material when they soak up such a large part of an individual’s budget.

Some people, especially now, make the mistake of thinking that they’re getting richer because they’re seeing their assets go up in price without seeing how their buying power is being eroded. The ones who are most hurt are those who have their money in cash and fixed-rate credit assets.

As mentioned, this money and credit that’s been created is a lot more than the supply of real things (i.e., goods and services) and various types of investments assets (e.g., stocks, homes, commodities, etc.).

This causes the nominal value of these assets to go up, but that doesn’t mean they’re giving people more buying power when the money these assets are denominated in is being devalued.

When you are seeing your financial wealth go up it’s important for people to view these things critically and not think they are gaining lots of real wealth when their buying power is going down.

This is especially true now that lots of investment assets are seeing their rate of appreciation decline (or even fall) with the rise in interest rates and are now lagging the inflation rate.

Most Americans (and those in most developed markets today) today have never experienced these conditions and they’re so accustomed to measuring their wealth in nominal terms without thinking about how their buying power is changing.

Wages

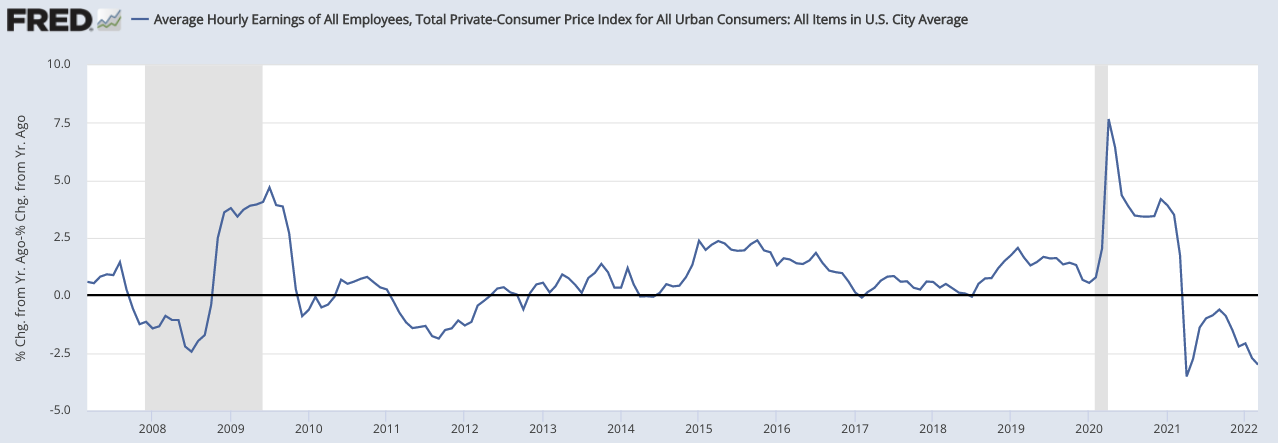

The same thing applies to wages, not only investment assets.

People are seeing their wages go up at work by the fastest rate in decades. But for the average person, these wage gains are less than the rate their buying power is falling. So despite the headline – “wage gains fastest in decades” – the average person is currently seeing wage cuts in real terms.

Real wage gains (United States)

(Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

The amount of money the average person is getting is going up but they’re getting squeezed and can afford less. The amount of wealth they have is not the same thing as the amount of money they have.

Investments

The same holds true for investments.

Let’s say hypothetically you own a house that’s worth $800k. It could go up from $800k to $1mm in 5 years.

That sounds good, but if you annualize that gain, it’s only 4.5 percent.

If inflation persists above 4.5 percent – which is the case – you haven’t gained money despite your house “going up in value”. You’ve lost money and you’ve had all those carrying costs throughout it all.

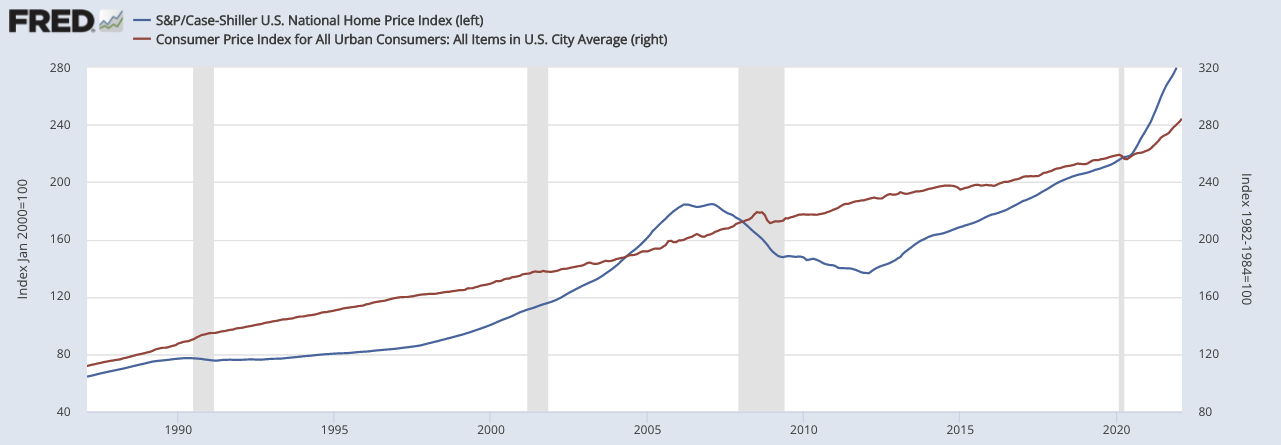

It’s also common to hear things like a house going up substantially in value over decades. But those also need closer inspection.

For example, you might hear of things like how someone bought a home for $100k in 1973 and that same home today is now worth $675k, ostensibly representing a huge gain.

Annualizing that, it’s 3.9 percent.

Inflation has been 3.9 percent in the US over that time.

Real returns have been zero. In other words, that house hasn’t produced any actual real wealth gains even taking out all the costs associated with it.

And this makes sense – the house is the same house. The value of money has changed, but the house hasn’t really changed.

So real wealth gains are not a reliable assumption. We covered in a separate article about how well real estate tracks inflation.

It’s only been an imperfect inflation buffer.

National Home Price Index (blue) vs. CPI inflation rate (red)

(Sources: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

So while $100k to $675k sounds like a lot over around 50 years, it just mirrors how the prices of goods and services have changed over that period.

Carrying costs

The above example neglects to consider carrying costs, which matter a lot because they’re cash outlays.

Think about how much money the house has taken to maintain over the years and keep compliant with taxes and so on (and will continue to require).

If you express annual carrying costs as a percentage of the value of the home then add the annualized inflation rate (i.e., the amount of your home appreciation that doesn’t represent actual real wealth gains) and compare them to the paper gains, then it’s lost money even before accounting for transaction costs if the equity needs to be cashed out.

This is understandable because it’s just a primary home, so a lot of people would just dismiss them as “living expenses” or your personal burn rate.

But this is also why a primary home is typically not a very good investment. Its primary purpose is just shelter/a place to live, not typically to bring in income.

Example

Say, for example, you purchase a house for $400k, and 10 years later you sell it for $600k.

Good investment?

The $200k gain looks nice until unless you look carefully at the numbers.

If the house cost you $2,500 per month for principal, interest, taxes, and insurance (PITI), another $500 per month for utilities, you will have spent $36,000 per year, or $360,000 for the decade that you lived in the house.

If you spent another $5,000 per year on routine repairs and maintenance per the “one percent rule” (of the value of the property), you will have spent another $50,000.

And if you did some of the more major costlier repairs, such as replacing the roof and flooring, and remodeling the kitchen and bathrooms, you probably easily put in another $100,000 during the decade.

That’s a total of $510k over a 10-year period, to get a $200k gain on the sale.

While it may feel nice to make $200k more than you paid for it, the math doesn’t support the idea of the house as a winning investment.

And that’s before accounting for inflation, transaction costs (e.g., six percent realtor fees, other costs), and the possibility that the house won’t appreciate like that.

Because people notice the $200k a lot more than the rather slow bleed of the $510k over the course of a decade, they pay a lot more attention to what they netted from the sale (in nominal terms), they think they made a good investment when it was actually a bad one.

If you also add transactions costs, which can easily be 10 percent of the home’s sale price (knocking you down to $540k) and inflation of ~3 percent annually, that $200k nominal gain is also eroded away entirely.

Homeownership expenses list

Owning a home comes with a variety of expenses.

Here is a list of common costs associated with homeownership:

- Mortgage payments: Monthly payments on your home loan, including principal and interest.

- Property taxes: Annual taxes levied by local governments, based on the assessed value of your property.

- Homeowners insurance: Insurance policy to protect your home and belongings from damage or theft. Premiums are often paid annually or monthly.

- Private mortgage insurance (PMI): If your down payment is less than 20% of the home’s purchase price, you may be required to pay PMI, which protects the lender in case you default on your loan.

- Homeowners association (HOA) fees: If you live in a community with an HOA, you may need to pay monthly or annual fees for shared amenities and maintenance.

- Utility bills: Costs for electricity, gas, water, sewer, and trash services.

- Maintenance and repairs: Regular upkeep and unexpected repairs, such as plumbing issues, HVAC maintenance, roof repairs, and appliance replacements.

- Lawn care and landscaping: Expenses for maintaining the yard, such as mowing, trimming, and fertilizing.

- Pest control: Regular inspections and treatments to prevent or eliminate pests, such as termites, rodents, or insects.

- Home improvements and renovations: Costs associated with updating or remodeling your home, such as new flooring, kitchen upgrades, or bathroom remodels.

- Appliance and systems maintenance: Regular servicing and eventual replacement of appliances and systems, like your water heater, furnace, air conditioner, or refrigerator.

- Exterior maintenance: Expenses for maintaining the exterior of your home, such as painting, siding repairs, gutter cleaning, and roof maintenance.

- Moving costs: Expenses related to moving into or out of the home, such as hiring a moving company or purchasing packing materials.

- Closing costs: One-time fees paid when purchasing a home, which can include loan origination fees, appraisal fees, title insurance, and recording fees.

It’s important to remember that expenses can vary based on factors like the size, age, and location of the home, as well as the homeowner’s lifestyle and preferences.

To get a clear understanding of the costs associated with owning a specific home, it’s helpful to create a detailed budget that includes all potential expenses.

Real wealth gains in US real estate

The real wealth gains in the US real estate market over the past 100 years are less than 1 percent annualized. But that just takes the asset class at face value.

It doesn’t account for the aforementioned carrying costs, which eat up a lot of people’s budgets and they typically don’t earn any income from their homes.

The only places where real wealth gains have been seen are in highly desirable markets.

NYC has been one of these, for example – with the benefit of hindsight – but how appropriate would it be to extrapolate this trend into the future? You’re more likely to have regression to the mean.

“A house is not an investment risk”

Owning a house outright isn’t an investment risk as long as you can:

- comfortably make the payments associated with owning it

- you don’t need the equity in it for anything (in which case its underlying value isn’t a material concern), and

- such costs and commitment are not holding you back from other things that you’d like to have or be doing relative to your alternatives

Strategic & Financial Implications of Owning a Home

Let’s break down the strategic implications and other financial considerations:

Strategic Implications

Ongoing Expenditures vs. Economic Return:

It’s essential to differentiate between:

- the ongoing costs of owning a home and

- the all-in economic return over time

While the former is typically just expenditures in standard owner-occupied cases, the latter is speculative and unlikely to result in a net gain when factoring in inflation and net holding costs.

The latter can’t be thought of as simply the nominal return.

Equity Trapping:

Equity in a home is not liquid.

Borrowing against it can come with high fees and unfavorable interest rates.

Therefore, relying on home equity for immediate financial needs may not be the best strategy.

Real vs. Nominal Returns:

A nominal increase in the price of a home is only one factor.

It’s important to factor in inflation (buying power is what matters with everything) when assessing the value of one’s assets and the revenue/expense picture when considering the total economic return.

Holding Costs:

These are recurring expenses that don’t contribute to the real growth of the property’s value.

They can vary widely based on several factors (e.g., location, the age and condition of the property, owner’s lifestyle, etc.) and can significantly impact the net return on a property.

Expressed annually as a percentage of the value of the home, low-end figures are typically 2-3%; on the high end, you see figures of around 9% when everything is divided out.

Many projects that create substantial outlays aren’t relevant on an annual timeframe (e.g., most repairs, maintenance, and renovations).

The timing also matters. Lots of upfront costs versus decisions that are many years away.

Global Context:

For example, Turkey’s housing market (very high nominal gains offset by terrible inflation and costs) illustrates that the economic picture isn’t the nominal returns.

Housing as a Consumption Decision:

A home should primarily be viewed as a place to live rather than an investment.

Financial advisors typically advise against buying more house than necessary.

Limited Optionality:

Selling a home often leads to purchasing another because a home is a basic need.

Accordingly, there’s less optionality to it in comparison to selling something that you don’t need (e.g., stock, bond, rental property).

Additional Financial and Strategic Considerations

Diversification:

Putting a significant portion of one’s wealth into a single asset (like a home) can be risky, especially if it’s cash flow-negative and produces a negative all-in real return.

Liquidity Needs:

Homes are illiquid assets.

If there’s a sudden need for cash, selling a home can be time-consuming and might not fetch the desired price.

Interest Rates:

Mortgage rates can significantly impact the cost of owning a home.

It’s essential to consider current and potential future rates when making housing decisions.

Tax Implications:

In some jurisdictions, there are tax benefits associated with mortgage interest or property taxes. However, these benefits can change based on tax laws.

Market Conditions:

The housing market can be cyclical, given it’s a debt- and interest rate-sensitive asset.

Alternative Investments (Opportunity Cost):

Before purchasing a home, consider if that’s the best decision versus buying investment assets that create income.

Rent vs. Buy Analysis:

In some markets, renting might be more financially advantageous than buying.

From an opportunity cost perspective, renting might make more sense for many people.

It’s essential to analyze the total costs of both options before making a decision.

Emergency Fund:

Homeowners should have an emergency fund to cover unexpected expenses, such as repairs or periods of unemployment.

Long-term Goals:

Consider how a home fits into long-term financial and life goals.

For instance, if there’s a possibility of relocating for work, buying might not be the best choice.

Overall, while a home can be a source of pride and stability, it’s important to approach it with a clear financial understanding.

Is real estate better than investing in stocks?

Stocks and real estate are both forms of equity. A stock isn’t just a piece of paper; it’s a securitization of a stream of cash flows generated from the assets of the company. The securitization simply makes it liquid and its values are marked to market, unlike most real estate, which isn’t securitized, and is illiquid and traded privately.

A piece of real estate generates cash flow generated from the land or property, either from renting it out or some other economic activity. A primary home doesn’t do that unless parts of it are rented out or economic value is derived from it in some other way.

How do I know if my home is a good investment?

A good exercise is to take your total burn rate on your home (e.g., taxes, maintenance, utilities, insurance, and so on) as an annual figure and divide it by the estimated value of your home.

That’ll give an idea of how much appreciation would be needed just to break even on it. For example, if your net burn rate is $3,000 per month and its value is $750k, the annual appreciation needed to break even is $36k/$750k, or 4.8 percent.

They can also take into account their accrued tax benefits (i.e., tax savings).

Most people aren’t going to get that and shouldn’t be owning a house that’s an excessive part of their budget under the premise that it’s an investment because very rarely is it earning them more money in appreciation than the all-in expenses.

If people are managing to derive income from their primary residence in some way, or it saves them money in some fashion, then it changes the equation. The all-in picture has to be taken into consideration.

Can I sell a portion of my home equity?

There are fintech firms like Hometap, Unison, EasyKnock, Point, Unlock, among others that do partial equity cash-outs so people can sell a fraction of their home.

However, these firms are usually going to have strict requirements on where their investment goes.

They’re typically going to ask that the money doesn’t sit in cash for the owner for a buffer or lifestyle, but is used to make improvements to the property that go beyond basic maintenance.

Otherwise, if no improvements are being made – not just fixing things that were already there but adding new capacity, new additions, etc. – to boost the real value of the house, then the house is just like a very impure inflation-indexed bond with more risk and no earnings until it’s sold, which triggers transactions costs.

If, for example, the majority owner simply wanted $100k in cash, which can lose hundreds or up to $1,000/mo to inflation, or it’s just to keep up maintenance and carrying costs (which is burnt money/carrying costs), and the partial owner has a primary residence that they don’t live in and don’t get monthly income from, then there’s value destruction for both sides of the deal.

There needs to be a value creation process tied to the investment beyond just basic appreciation in the home, which is not reliable.

Investment drawbacks of primary homes

Primary (owner-occupied) homes are a necessity, as you need to live somewhere.

But from an investment perspective, you’ll have to deal with the following:

- The down payment is often the biggest one-time outlay of cash that many people will have to make in their lives (for an asset that won’t generate them an income).

- Beyond the down payment, it is a consistent drain on cash reserves. Repairs and maintenance, utilities, interest, insurance, property taxes, and other fees make it expensive to own.

- This drain on cash reserves takes up a significant portion of one’s take-home pay and limits the ability to diversify.

- It’s illiquid. It can take months to sell (and in some cases years). Moreover, it takes effort to sell.

- They are expensive to buy and sell due to the high transaction costs between realtors and closing costs.

- It’s complex to buy and sell, which means lots of other parties will need to be looped in for extra documents, reports, and the charges that come with them.

- There are not only property taxes but taxes when it goes up in value.

- Its return is low, about in line with inflation.

- You pay it; it doesn’t pay you.

- It’s not portable, which means only certain buyers will be available to purchase it from you if you wish to sell it.

- It’s tied to the fortunes of not just a country, state, city, or town, but a single neighborhood. If local jobs leave, tax rates go up, neighbors become iffier, something with the local environment changes, it could cause a home’s value to drop.

- The asset is fragile and easily damaged by weather, vandalism, and so on.

- Having the asset effectively tie you to one geographical area can limit the owner’s options.

- It’s usually impossible to divide.

Home equity as a percentage of wealth across the US wealth distribution

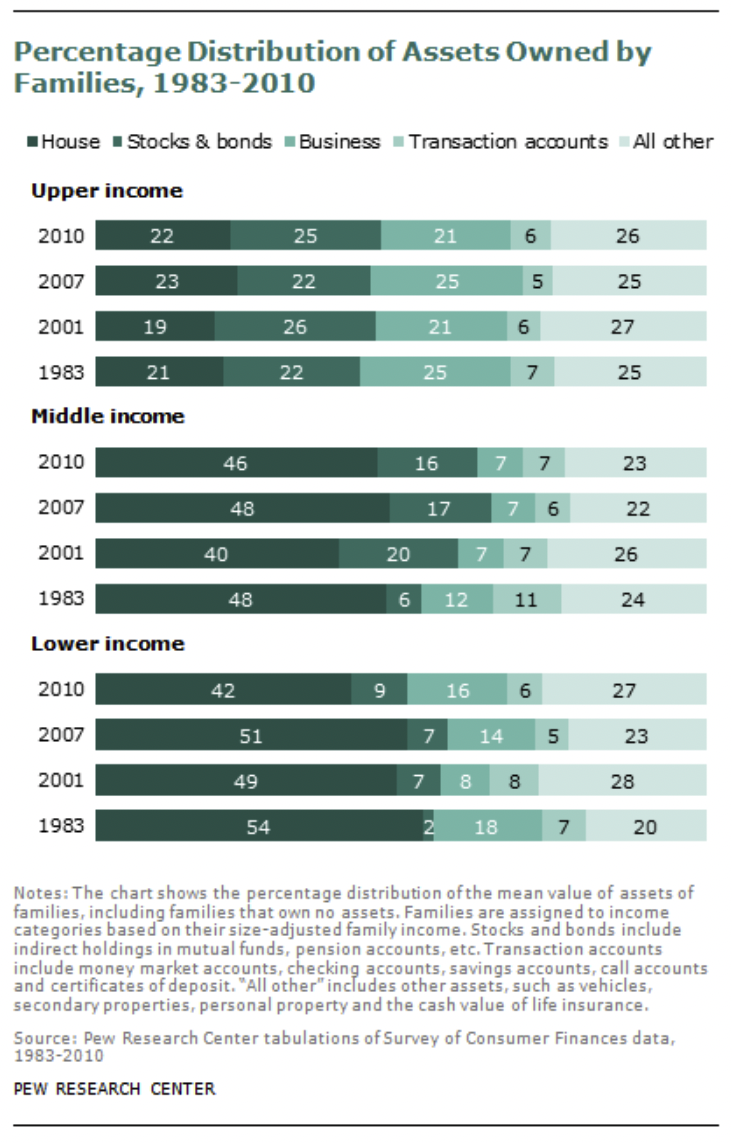

Pew Research, in a study running from 1983 to 2010, found that low-income households (average net worth of approximately $105k) and middle-income households (approximate net worth of $235k) had 40 to 50 percent of their net worths wrapped up in home equity.

Upper-income households (approximate net worth of $1.8 million) had just over 20 percent of their net worths in home equity.

Naturally, a big part of this has to do with the fact that shelter is a basic necessity.

So lower- and middle-income earners often don’t have enough disposable income to invest because their home (if they do own one) is expensive. Higher earners can afford to diversify more.

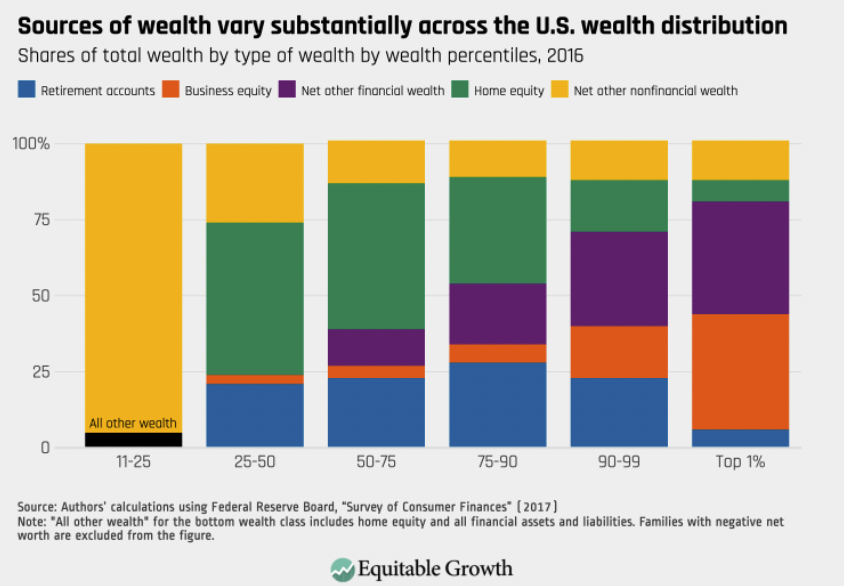

A separate study divided wealth into six percentile buckets – 11-25, 25-50, 50-75, 90-99, and 99+.

(Source: Equitable Growth)

Home equity constituted a huge fraction of the wealth of the 25-90 percentiles in the US.

The middle quartiles – 25-50 and 50-75 – have about half their wealth locked up in their personal residence.

It was a small part of the top 1 percent, as at that level so much comes from business equity and other financial wealth (about 80 percent of total wealth).

They are able to diversify much more heavily. At some level, there may also be some recognition that the home they live in isn’t the best investment relative to their universe of alternatives and don’t go overboard with the purchases of personal residences.

The amount of wealth in “other nonfinancial wealth” also stayed relatively constant across wealth tiers beyond the 50th percentile, at 10 to 15 percent of overall wealth.

Price falls in residential housing

Some tend to believe that houses are a safe investment because their prices tend to “only go up”.

But there are times when they do decline.

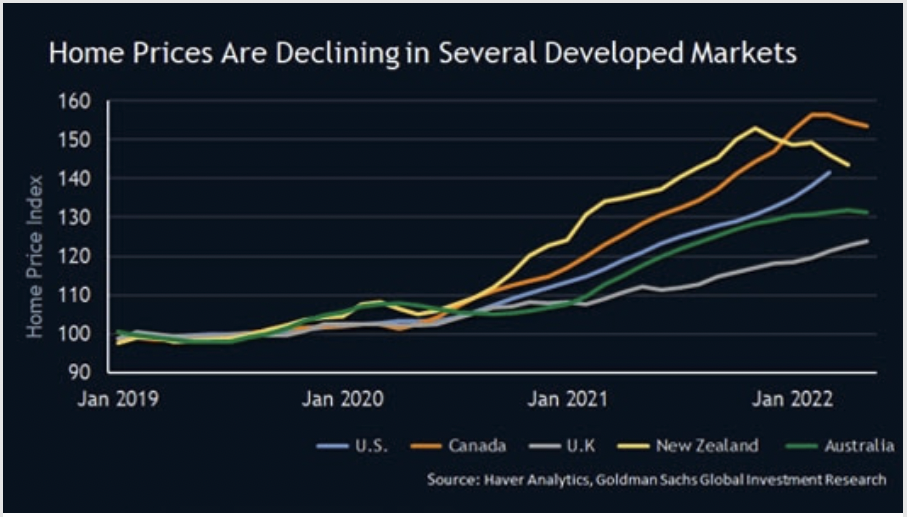

The housing picture in many countries in recent years showed a stark change underway, with already substantial declines in sales across developed economies.

Rises in inflation forced central banks to tighten, which hit the values of most financial assets. Homes also have a large financial component to them because the bulk of them are bought on credit.

By mid-2022, home sales were down by 40 percent from their peak in the US, and by half in the UK

Those sales declines are meaningful for prices in the near future. Based on Goldman Sachs Research estimates, a 10 percentage point slowdown in house sales growth tends to be followed by a 2 percentage point slowdown in house price growth in around six months.

By mid-2022, home prices were still rising in the likes of the US, Germany and the UK, they are already declining across Australia, Canada, Sweden and New Zealand.

Costs over the lifetime of a mortgage

Today’s buyer of a typical $550,000 single-family home who takes out a 30-year mortgage loan will end up paying the price of the house again just in interest. Add 30 years of property taxes, homeowner’s insurance, regular maintenance, a couple big-ticket repairs or improvements, and the total cost of buying the home could easily top out at over $2 million, including the benefits of tax deductions.

Real (inflation-adjusted) home price increase are about 0 percent over time (0-1 percent in the US historically) simply because that’s about where real wages have stood. And over time, the debt and interest rate cycles about balance themselves out.

So the typical home doesn’t appreciate at all when purely considering the purchasing power of the money, but of course it has all the expenses along the way.

Final word

Someone believing that they’ll have more money in the future – in anticipation that the price of some asset they have will go up – doesn’t mean that they will have more wealth (buying power).

The United States and other governments are now spending a lot more money than it’s earning and has liabilities above its assets and is paying for it by printing money that is being devalued.

Governments’ ability to tax can only go up to a certain level because people will vote out those high-taxing governments and replace them with ones who don’t promote those policies.

To make up the deficit, the devaluation of money by creating it is a discreet tax that keeps the bills paid in nominal terms and can cause a lot more inflation of various different things depending on where the money is being spent.

In the case of inflation, people who hold cash and fixed-rate credit assets have to pay it because those are the assets that are being devalued.

Things like stocks, commodities, and real estate go up in relation to the devalued money.

But this doesn’t mean things like primary residences are better investments.

Primary homes have such a huge consumption element to them that they are not really winning investments (something that earns you more in buying power over time). They have carrying costs, transaction costs in order to get the liquidity out, and inflation that eat away at the appreciation (and tax benefits from owning real estate), which is not guaranteed anyway.

It’s just shelter/an expense. The idea of owning more house than necessary for one’s own needs because “it’s an investment” is not a good one because very rarely is that true.

If, super conservatively, putting your money elsewhere would net you an inflation-adjusted return of 0 percent, average inflation over the long-run is 3 percent, and the carrying costs of a home’s value without a mortgage are 7 percent annually, then every $1,000 that goes into housing costs the $1,000 in would-be savings plus $100 in foregone income earned off of it.

That’s why it’s important to live below one’s means with a primary residence. The burn rate is very likely going to be more than the appreciation, so it should be treated as an expense.